SVM-Driven Cytoskeleton Gene Classification: Biomarker Discovery for Age-Related and Neurodegenerative Diseases

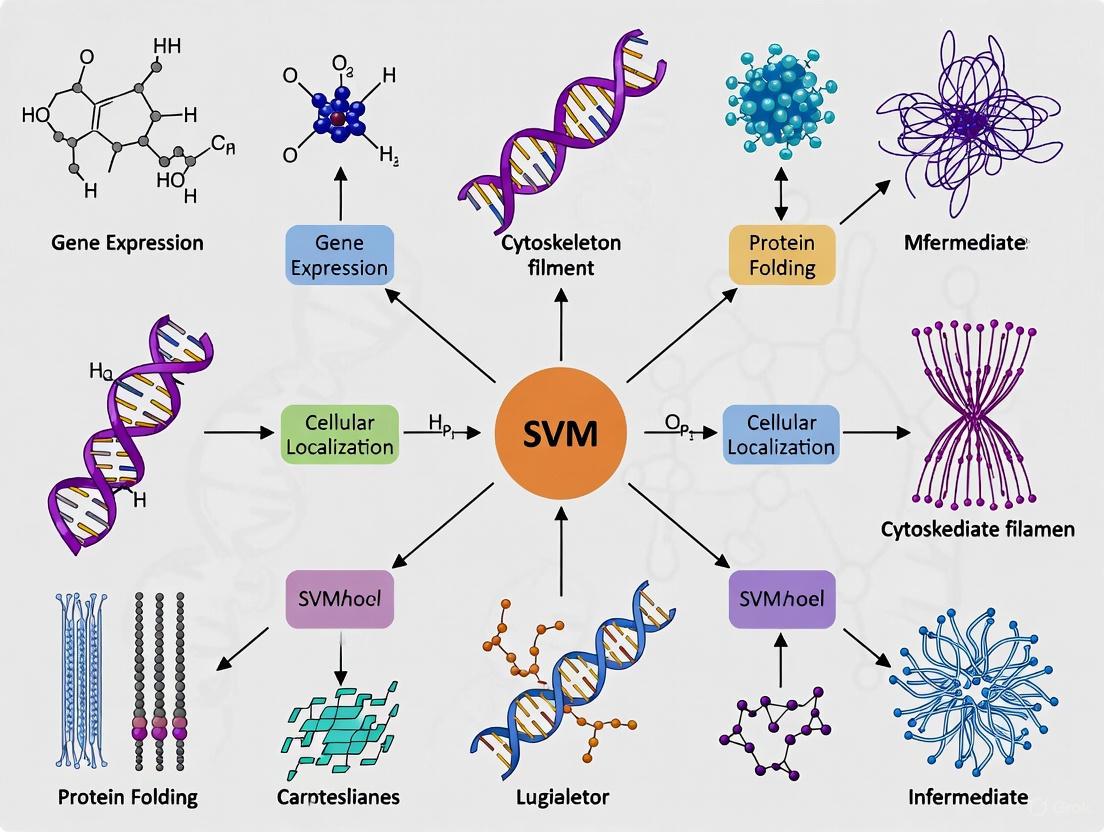

This article explores the integration of Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms with cytoskeleton genomics for advanced disease classification and biomarker discovery.

SVM-Driven Cytoskeleton Gene Classification: Biomarker Discovery for Age-Related and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

This article explores the integration of Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms with cytoskeleton genomics for advanced disease classification and biomarker discovery. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we cover foundational concepts linking cytoskeletal dysregulation to pathologies like Alzheimer's, cardiomyopathies, and diabetes. The content details methodological approaches including Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for gene selection, addresses troubleshooting for high-dimensional genomic data, and provides validation frameworks through comparative performance analysis. Recent advances and future directions for translating computational findings into therapeutic targets are also discussed, providing a comprehensive resource for leveraging SVM in cytoskeleton-focused biomedical research.

The Cytoskeleton-Gene-Disease Nexus: Establishing the Biological Framework for SVM Classification

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, intricate network of protein filaments that extends throughout the cytoplasm, serving as the primary structural framework for cellular integrity and function. This complex system is fundamental to maintaining cell shape, providing mechanical strength, enabling intracellular transport, and facilitating cell movement [1] [2]. Comprising three principal filament types—microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—the cytoskeleton demonstrates remarkable plasticity, rapidly assembling and disassembling in response to cellular requirements and environmental cues [1].

The critical importance of the cytoskeleton extends beyond basic cellular mechanics to human health and disease pathogenesis. Dysregulation of cytoskeletal components is implicated in numerous disease states, including neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, cancer progression, and various age-related conditions [1] [3]. Consequently, cytoskeletal research has garnered significant attention in both basic science and therapeutic development, with the global cytoskeleton market experiencing robust growth driven by advanced research techniques in cell biology, drug discovery, and diagnostics [4].

Table 1: Core Components of the Eukaryotic Cytoskeleton

| Filament Type | Diameter | Protein Subunit | Primary Functions | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfilaments | 7 nm | Actin (G-actin) | Cell movement, muscle contraction, cytokinesis, intracellular transport | Double helix of F-actin polymers, polarized (+/- ends) |

| Intermediate Filaments | 8-12 nm | Various (keratin, vimentin, lamin, desmin) | Mechanical strength, resistance to shear stress, organelle anchoring | Rope-like structure, two anti-parallel helices/dimers forming tetramers |

| Microtubules | 23 nm | α- and β-tubulin heterodimers | Intracellular transport, cell division, maintenance of cell polarity | Hollow cylinders composed of 13 protofilaments |

Molecular Composition and Structural Properties

Microfilaments (Actin Filaments)

Microfilaments are composed of globular actin (G-actin) monomers that polymerize to form filamentous actin (F-actin) structures. These filaments exhibit structural polarity, featuring a rapidly growing plus end (barbed end) and a slower-growing minus end (pointed end) [5] [2]. Actin polymerization is an energy-dependent process requiring ATP, with assembly and disassembly dynamics controlled by the ATP:ADP ratio in the cytoplasm [2]. The dynamic nature of microfilaments enables rapid remodeling in response to cellular signals, facilitating processes such as cell migration, phagocytosis, and cytokinesis.

Actin structures are precisely regulated by the Rho family of small GTP-binding proteins (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42), which control the formation of distinct actin-based structures [1]. Rho GTPases govern contractile actomyosin filaments (stress fibers), Rac regulates lamellipodia formation, and Cdc42 controls filopodia development. These molecular switches integrate extracellular signals with cytoskeletal rearrangements, allowing cells to adapt their architecture and motile behavior appropriately.

Microtubules

Microtubules are hollow cylindrical structures composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that assemble in a head-to-tail fashion to form protofilaments [5]. Typically, 13 protofilaments associate laterally to form the microtubule wall, creating a structurally rigid filament with a diameter of approximately 25 nm [1] [5]. Like microfilaments, microtubules exhibit structural polarity, with a plus end (β-tubulin exposed) that grows more rapidly and a minus end (α-tubulin exposed) that grows more slowly [5].

Microtubule dynamics are characterized by a phenomenon known as "dynamic instability," wherein individual microtubules undergo alternating phases of growth and shrinkage [5]. This dynamic behavior is crucial for cellular functions such as mitotic spindle formation during cell division and intracellular transport. The structural integrity and dynamics of microtubules are regulated by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) and motor proteins including kinesins and dyneins, which facilitate directional transport of vesicles, organelles, and other cargo throughout the cell [5].

Intermediate Filaments

Intermediate filaments provide mechanical strength and resistance to shear stress, forming a stable framework that maintains cellular structural integrity [1] [5]. Unlike microfilaments and microtubules, intermediate filaments are non-polar and assembled from a diverse family of proteins including keratins (in epithelial cells), vimentin (in mesenchymal cells), neurofilaments (in neurons), lamins (in the nucleus), and desmin (in muscle cells) [1] [5].

The assembly mechanism of intermediate filaments involves the formation of dimeric subunits through coiled-coil interactions of α-helical rod domains. These dimers then associate in a staggered anti-parallel fashion to form tetramers, which subsequently assemble into higher-order structures that ultimately form the mature 10-nm filament [1] [5]. This assembly configuration contributes to their exceptional mechanical stability and resilience. Intermediate filaments are more stable and less dynamic than microfilaments and microtubules, reflecting their primary role in providing long-term structural support and mechanical resistance [5].

Research Applications and Methodologies

Advanced Imaging Techniques

Cutting-edge imaging technologies have revolutionized our understanding of cytoskeletal architecture and dynamics. Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) enables visualization of cytoskeletal structures in near-native states at subnanometer resolution [6]. This technique involves rapid vitrification of biological samples to preserve their natural structure, followed by reconstruction of three-dimensional images from a series of tilted cryo-EM images [6]. Recent innovations combining optogenetics with cryo-ET allow precise temporal control over cytoskeletal dynamics, enabling researchers to capture ultrastructural changes during specific cellular processes such as lamellipodia formation [6].

Super-resolution light microscopy techniques, including GI-SIM (grid illumination structured illumination microscopy), have overcome the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy, permitting visualization of intracellular organelle and cytoskeletal interactions at nanoscale resolution on millisecond timescales [7]. These approaches reveal dynamic processes such as microtubule dynamic instability, mitochondrial fission and fusion, and organelle hitchhiking along cytoskeletal elements [7].

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

The integration of machine learning in cytoskeleton research has accelerated the identification of cytoskeletal components and their associations with disease states. Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers have demonstrated exceptional performance in analyzing cytoskeletal gene expression patterns, achieving high accuracy in identifying genes associated with age-related diseases including Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Coronary Artery Disease, Alzheimer's disease, Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus [3].

Machine learning frameworks have been successfully applied to analyze morphological changes in cytoskeletal elements. For instance, object recognition machine learning models can quantify structural features of astrocytes based on 15 different criteria, including cytoskeletal density, size, and branching patterns [8]. This approach has revealed that heroin exposure induces specific alterations in astrocyte cytoskeleton, causing cells to shrink and become less malleable [8].

Specialized computational tools like MTBPred leverage SVM and random forest algorithms to predict microtubule-associated and binding proteins (MTBPs) with high precision (93%) and recall (98%) [9]. This tool utilizes five key features that consistently yield high classification accuracy (>90%), providing researchers with a valuable resource for identifying novel cytoskeletal regulatory proteins.

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in Cytoskeleton Research

| Application Area | ML Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Gene Classification | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | High accuracy in identifying disease-associated genes [3] | Identification of biomarkers for age-related diseases |

| MTBP Prediction | SVM and Random Forest | Recall: 98%, Precision: 93% (SVM) [9] | Accelerated identification of microtubule-binding proteins |

| Astrocyte Morphology Analysis | Object Recognition ML | 80% accuracy in predicting anatomical origin [8] | Quantification of drug-induced cytoskeletal changes |

| Drug Discovery | Machine Learning Classifiers | Efficient screening of compound libraries [10] | Identification of natural inhibitors targeting tubulin isotypes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Visualizing Lamellipodia Dynamics Using Integrated Optogenetics and Cryo-ET

This protocol outlines procedures for investigating ultrastructural dynamics during lamellipodia formation through integration of optogenetics with cryo-electron tomography [6].

Materials and Reagents

- COS-7 cells (or other adherent cell line)

- Photoactivatable-Rac1 (PA-Rac1) plasmid

- Lifeact-mCherry plasmid for F-actin visualization

- Poly-L-lysine and laminin for grid coating

- EM grids (gold or quantifoil)

- Cryo-plunge freezing apparatus

- Confocal laser scanning microscope with environmental chamber

- Cryo-electron microscope with tomographic capabilities

Method

Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Culture COS-7 cells in appropriate medium under standard conditions.

- Transfect cells with PA-Rac1 and Lifeact-mCherry plasmids using preferred transfection method.

- Allow 24-48 hours for protein expression before experimentation.

EM Grid Preparation

- Coat EM grids with poly-L-lysine (0.1% w/v) for 10 minutes, followed by laminin (10 µg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Plate transfected cells onto coated EM grids and allow adhesion for 4-6 hours.

Optogenetic Induction and Vitrification

- Mount grid in plunge-freezer chamber with integrated blue light LED system.

- Irradiate cells with blue light (wavelength 458-488 nm) for 2 minutes to activate PA-Rac1 and induce lamellipodia formation.

- Immediately following irradiation, vitrify samples by plunge-freezing in liquid ethane.

- Store grids in liquid nitrogen until data collection.

Cryo-Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (Cryo-CLEM)

- Identify regions of interest using cryo-fluorescence microscopy.

- Transfer grid to cryo-electron microscope for tomographic data collection.

- Acquire tilt series from -60° to +60° with 1-2° increments at defocus of -4 to -8 µm.

Data Processing and Analysis

- Reconstruct tomograms using weighted back-projection or iterative reconstruction methods.

- Segment actin filaments and membrane structures using automated or manual approaches.

- Analyze filament orientation, density, and spatial relationships.

Technical Notes

- Maintain consistent temperature throughout optogenetic stimulation and vitrification.

- Optimize light intensity and duration to induce lamellipodia without cellular damage.

- Target areas with ice thickness appropriate for tomography (200-500 nm).

Protocol: Computational Identification of Cytoskeletal Biomarkers Using SVM Classification

This protocol describes a bioinformatics workflow for identifying cytoskeletal genes associated with diseases using machine learning approaches [3].

Materials and Software Requirements

- Gene expression datasets from disease cohorts (e.g., GEO, TCGA)

- List of known cytoskeletal genes (e.g., from Gene Ontology)

- Python or R programming environment

- Scikit-learn library for machine learning

- High-performance computing resources for large-scale analysis

Method

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Obtain transcriptomic datasets from relevant disease studies and healthy controls.

- Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM, FPKM).

- Annotate cytoskeletal genes using Gene Ontology terms (GO:0005856, GO:0005874).

Feature Selection and Engineering

- Calculate differential expression statistics between case and control groups.

- Select top differentially expressed cytoskeletal genes based on fold-change and adjusted p-value.

- Generate additional features including co-expression patterns, pathway enrichment scores, and protein-protein interaction network metrics.

Training Set Construction

- Compile known disease-associated cytoskeletal genes as positive training set.

- Select non-cytoskeletal genes or non-disease-associated cytoskeletal genes as negative training set.

- Address class imbalance using sampling techniques if necessary.

SVM Model Training and Validation

- Split data into training (70%) and validation (30%) sets.

- Train SVM classifier with radial basis function (RBF) kernel.

- Optimize hyperparameters (C, γ) using grid search with cross-validation.

- Evaluate model performance using metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC.

Biomarker Identification and Validation

- Apply trained model to independent test datasets.

- Rank predicted genes based on decision function values or probabilities.

- Validate top candidates using literature mining or experimental data.

Technical Notes

- Perform appropriate multiple testing correction for differential expression analysis.

- Consider ensemble methods combining SVM with other classifiers for improved performance.

- Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies to avoid overfitting.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeleton Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin Visualization | Lifeact-mCherry, Phalloidin conjugates | Live-cell imaging of microfilament dynamics [6] | F-actin labeling and stabilization |

| Optogenetic Tools | Photoactivatable-Rac1 (PA-Rac1) | Spatiotemporal control of signaling pathways [6] | Precise induction of cytoskeletal rearrangements |

| Tubulin Inhibitors | Taxol, Colchicine, Novel natural compounds [10] | Investigating microtubule dynamics and drug development | Modulation of microtubule stability and polymerization |

| Machine Learning Tools | MTBPred, Custom SVM classifiers [3] [9] | Prediction of cytoskeletal associations and biomarkers | Automated analysis of complex datasets and patterns |

| Cryo-ET Reagents | Poly-L-lysine, Laminin-coated grids [6] | Structural biology of cytoskeletal components | Sample preparation for high-resolution tomography |

| Antibody Panels | Anti-βIII-tubulin, Anti-Arp2, Anti-Abi1 [6] [10] | Protein localization and expression studies | Specific detection of cytoskeletal proteins |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The cytoskeleton functions as an integrative platform for numerous signaling pathways that regulate cellular architecture and behavior. Small GTPases of the Rho family (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) serve as master regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics, transducing extracellular signals into coordinated structural changes [1] [5]. Rac1 activation stimulates lamellipodia formation through the SCAR/WAVE complex, which subsequently activates the Arp2/3 complex to nucleate branched actin networks [6]. The Arp2/3 complex binds to existing actin filaments and initiates new filament growth at approximately 70° angles, creating the branched network characteristic of lamellipodia [6].

Microtubule dynamics are regulated by numerous microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) and signaling pathways. Tubulin isotypes, particularly βIII-tubulin, influence microtubule stability and drug sensitivity [10]. Overexpression of βIII-tubulin in various carcinomas confers resistance to taxane-based chemotherapeutics, making it an important therapeutic target [10]. Computational studies integrating structure-based drug design with machine learning have identified natural compounds that selectively target the βIII-tubulin isotype, offering promising avenues for overcoming drug resistance [10].

Intermediate filaments provide mechanical stability and serve as scaffolds for signaling molecules. Their cell-type-specific composition (keratins in epithelial cells, vimentin in mesenchymal cells, neurofilaments in neurons) allows specialized functions tailored to tissue requirements [1] [5]. Mutations in intermediate filament proteins cause severe medical conditions including premature aging, muscular dystrophy, and Alexander Disease, underscoring their critical role in cellular integrity [1].

The cytoskeleton represents a sophisticated integration of structural and regulatory elements that collectively maintain cellular integrity and function. Understanding the intricate interplay between microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments provides crucial insights into fundamental biological processes and disease mechanisms. The emerging integration of advanced imaging techniques like cryo-ET with computational approaches such as SVM classification represents a powerful paradigm for accelerating cytoskeleton research.

Future research directions will likely focus on elucidating the spatiotemporal coordination between different cytoskeletal networks, developing more sophisticated machine learning models for predicting cytoskeletal behavior, and translating basic research findings into therapeutic applications. The continued refinement of optogenetic tools and high-resolution imaging methodologies will enable unprecedented visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics, while computational approaches will facilitate the identification of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cytoskeleton-related diseases.

Application Notes

The cytoskeleton, comprising actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, is a dynamic network critical for maintaining cellular structural integrity, facilitating intracellular transport, and enabling mechanotransduction [11] [12]. Dysregulation of cytoskeletal components and their associated proteins is increasingly recognized as a fundamental pathological mechanism spanning diverse human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular conditions, and metabolic diseases [11] [13] [14]. Recent advances in computational biology, particularly machine learning approaches, have enabled more precise identification of cytoskeleton-related gene signatures associated with these conditions, opening new avenues for biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting [11] [15].

The integration of support vector machine (SVM) classification with transcriptomic data has emerged as a powerful methodology for identifying cytoskeletal gene patterns that accurately discriminate between diseased and normal states across multiple age-related pathologies [11]. This approach has revealed distinct cytoskeletal gene expression profiles associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), coronary artery disease (CAD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), providing a molecular framework for understanding shared and unique pathophysiological mechanisms [11] [12].

SVM-Based Classification of Cytoskeletal Genes in Age-Related Diseases

Experimental Workflow and Performance Metrics

The application of SVM classifiers to cytoskeletal gene expression data has demonstrated exceptional accuracy in distinguishing disease states from healthy controls across multiple pathological conditions [11]. The recursive feature elimination (RFE) method coupled with SVM has proven particularly effective in identifying minimal gene signatures that maintain high diagnostic precision while reducing computational complexity [11].

Table 1: SVM Classifier Performance Across Age-Related Diseases

| Disease | Accuracy | Number of Cytoskeletal Genes Analyzed | Key RFE-Selected Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) | 94.85% | 1,696 | ARPC3, CDC42EP4, LRRC49, MYH6 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | 95.07% | 1,989 | CSNK1A1, AKAP5, TOPORS, ACTBL2, FNTA |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 87.70% | 1,561 | ENC1, NEFM, ITPKB, PCP4, CALB1 |

| Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM) | 96.31% | 2,167 | MNS1, MYOT |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) | 89.54% | 2,188 | ALDOB |

The exceptional performance of SVM-based classification across these diverse disease states underscores the fundamental role of cytoskeletal dysregulation in age-related pathologies and highlights the potential of machine learning approaches for identifying robust diagnostic biomarkers [11]. The RFE-SVM pipeline successfully identified 17 key cytoskeletal genes involved in the structure and regulation of the cytoskeleton that demonstrate consistent association with age-related diseases, providing potential targets for therapeutic intervention [11] [12].

Cross-Disease Analysis of Cytoskeletal Gene Signatures

Comparative analysis of RFE-selected cytoskeletal genes across multiple diseases has revealed both disease-specific patterns and shared molecular pathways [11]. While no single gene was common to all five diseases examined, several genes demonstrated overlap across multiple conditions, suggesting possible shared pathological mechanisms:

- ANXA2 was common to AD, IDCM, and T2DM

- TPM3 was shared between AD, CAD, and T2DM

- SPTBN1 was identified in AD, CAD, and HCM

- MAP1B, RRAGD, and RPS3 were shared between AD and T2DM

- JAKMIP1, ABLIM3, and PDE4B were common to AD and CAD

These overlapping genes represent particularly promising candidates for further investigation as they may point to core cytoskeletal disruption mechanisms that transcend traditional disease classification boundaries [11].

Protocols

Protocol 1: SVM-Based Classification of Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Signatures

Purpose To classify disease states and identify discriminative cytoskeletal genes using SVM machine learning algorithms applied to transcriptomic data.

Materials

- Transcriptomic datasets (e.g., GEO Accession: GSE32453, GSE36961 for HCM; GSE113079 for CAD; GSE5281 for AD; GSE57338 for IDCM; GSE164416 for T2DM) [11]

- Cytoskeletal gene list from Gene Ontology Browser (GO:0005856) encompassing 2,304 genes [11]

- Computational environment with R or Python programming capabilities

- Limma package for batch effect correction and normalization [11]

- Scikit-learn or equivalent machine learning library with SVM implementation

Procedure

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Retrieve transcriptomic data from public repositories (see Materials for specific accession numbers)

- Perform batch effect correction and normalization using the Limma package [11]

- Filter genes to include only cytoskeletal-associated genes based on GO:0005856

Feature Selection using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

- Implement RFE with SVM classifier using linear kernel

- Recursively remove features with smallest weights with a step size of 1

- Calculate five-fold cross-validation scores at each step

- Select optimal feature subset based on peak cross-validation accuracy [11]

SVM Model Training and Validation

- Partition data into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets

- Train SVM classifier with linear kernel on selected feature subset

- Validate model using stratified five-fold cross-validation

- Assess performance using accuracy, F1-score, recall, precision, and ROC analysis [11]

Differential Expression Analysis

- Perform differential expression analysis using DESeq2 for T2DM and Limma for other diseases

- Apply thresholds of adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1

- Identify overlapping genes between RFE-selected features and differentially expressed genes [11]

Troubleshooting

- For class imbalance issues, employ stratified sampling during cross-validation

- If feature selection is unstable, increase step size in RFE or apply additional regularization

- For non-linear relationships, explore SVM with radial basis function kernel

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Cofilin-Actin Rod Formation in Neurodegenerative Models

Purpose To induce and quantify cofilin-actin rod formation as a marker of cytoskeletal dysregulation in cellular models of neurodegeneration.

Background Cofilin-actin rods are cytoplasmic structures containing predominantly dephosphorylated (active) cofilin and ADP-actin in a 1:1 ratio that form under conditions of oxidative or energetic stress and are associated with neurodegenerative processes, particularly Alzheimer's disease [13]. These structures are thought to interfere with intracellular transport and contribute to synaptic dysfunction [13].

Materials

- Cultured hippocampal neurons or immortalized cell lines (HeLa, HEK 293) [13]

- Cofilin and actin antibodies for immunocytochemistry

- Chemical inducers: 10 mM sodium azide (NaN3) with 6 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) for ATP depletion; 10 μM hydrogen peroxide for oxidative stress; 150-300 μM glutamate for excitotoxicity [13]

- Fluorescence microscope with high-resolution imaging capabilities

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler)

Procedure

Cell Culture and Stress Induction

- Plate cells on poly-D-lysine coated coverslips at appropriate density

- At 70-80% confluence, treat with stress-inducing compounds:

- For ATP depletion: 10 mM NaN3 + 6 mM 2-DG for 30 minutes

- For oxidative stress: 10 μM hydrogen peroxide for 60 minutes

- For excitotoxicity: 150-300 μM glutamate for 30 minutes [13]

Immunofluorescence Staining and Imaging

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes

- Block with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour

- Incubate with primary antibodies against cofilin and actin overnight at 4°C

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature

- Mount coverslips and image using confocal microscopy [13]

Quantification and Analysis

- Acquire images from multiple random fields per condition

- Count cells containing cofilin-actin rods (defined as elongated cytoplasmic inclusions >2μm in length)

- Calculate percentage of cells with rods per condition

- Quantify rod size and distribution using image analysis software

Troubleshooting

- Note that Lifeact and phalloidin do not effectively stain cofilin-actin rods [13]

- If rod formation is inconsistent, verify stressor concentrations and treatment duration

- For primary neurons, optimize culture conditions to maintain neuronal health before stress induction

Visualizations

Diagram 1: SVM-RFE Workflow for Cytoskeletal Gene Identification

SVM-RFE Cytoskeletal Gene Identification

Diagram 2: Cytoskeletal Dysregulation Pathways in Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases

Cytoskeletal Dysregulation Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cytoskeletal Dysregulation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Markers | Anti-cofilin, anti-actin, anti-tau antibodies | Detection of cytoskeletal components and their pathological aggregates in immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry |

| Stress Inducers | Sodium azide, 2-deoxyglucose, hydrogen peroxide, glutamate | Induction of cytoskeletal stress responses including cofilin-actin rod formation [13] |

| Computational Tools | Limma package, SVM algorithms (Scikit-learn), RFE implementation | Analysis of transcriptomic data and identification of cytoskeletal gene signatures [11] |

| Cell Models | Cultured hippocampal neurons, HeLa cells, HEK 293 cells | In vitro modeling of cytoskeletal dysregulation under controlled conditions [13] |

| Imaging Reagents | Fluorescently-labeled phalloidin, Lifeact (note: does not stain cofilin-actin rods) [13] | Visualization of actin structures (with limitations for specific pathological aggregates) |

The integration of computational approaches, particularly SVM-based classification, with experimental investigations of cytoskeletal dynamics provides a powerful framework for understanding shared pathological mechanisms across neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases. The protocols outlined here enable researchers to identify cytoskeletal gene signatures associated with specific disease states and validate their functional significance in relevant model systems. The consistent implication of cytoskeletal dysregulation across these diverse conditions suggests potential for shared therapeutic strategies targeting cytoskeletal stability and dynamics.

Fundamentals of Support Vector Machines (SVM) for High-Dimensional Biological Data Classification

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) represent a set of supervised learning methods widely used for classification, regression, and outlier detection in bioinformatics. Their core principle involves finding a hyperplane that optimally divides a dataset into distinct classes, which is particularly valuable for high-dimensional biological data where the number of variables (e.g., genes) far exceeds the number of observations. Introduced by Vladimir Vapnik and his collaborators in the 1990s, SVMs have gained popularity due to their high prediction accuracy, ability to handle structured data, and flexibility in integrating various data types [16] [17].

In the context of high-dimensional biological data such as gene expression microarrays, where each observation may involve thousands of gene measurements but only dozens of samples, traditional statistical methods often fail. SVMs excel in these "large p, small n" scenarios due to their margin-maximization principle and capacity to manage complexity through kernel functions [18] [19]. This technical note explores the fundamental concepts, protocols, and applications of SVMs specifically for classifying high-dimensional biological data, with emphasis on cytoskeletal gene classification in age-related diseases.

Theoretical Foundations of SVM

Core Concepts and Terminology

- Hyperplane: In an n-dimensional space, a hyperplane is a flat subspace of dimension n-1 that serves as a decision boundary separating different classes of data points.

- Support Vectors: These are the critical data points closest to the hyperplane that directly influence its position and orientation. The SVM algorithm essentially depends on these points to define the optimal separating boundary.

- Margin: The distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points from either class. SVM optimization aims to maximize this margin to enhance model generalization to new data.

- Kernels: Functions that transform input data into higher-dimensional spaces, enabling linear separation of non-linearly separable data. Common kernel functions include linear, polynomial, and Gaussian (Radial Basis Function or RBF) kernels [16].

Mathematical Formulation

Given a training dataset of m samples (x₁,y₁),···,(xₘ,yₘ) where xᵢ is an observation and yᵢ ∈ {-1, +1} is its class label, the standard linear SVM solves the following optimization problem [17]:

Minimize: ½∥w∥² + C∑ξᵢ

Subject to: yᵢ(wᵀxᵢ + b) ≥ 1 - ξᵢ ξᵢ ≥ 0

Here, w is the weight vector, b is the bias term, C is a regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin and minimizing classification errors, and ξᵢ are slack variables that permit misclassifications. For non-linearly separable data, the kernel trick replaces xᵢᵀxⱼ with k(xᵢ,xⱼ) = φ(xᵢ)ᵀφ(xⱼ), where k is a kernel function and φ is a mapping to a high-dimensional feature space [17].

SVM Protocol for High-Dimensional Biological Data Classification

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for applying SVM to high-dimensional biological data classification, specifically for cytoskeletal gene expression analysis:

Detailed Experimental Procedures

Protocol 1: Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

Purpose: Prepare high-dimensional biological data for SVM classification and identify the most informative features.

Materials and Reagents:

- Gene expression datasets (e.g., from GEO Accession numbers GSE32453, GSE36961 for HCM studies)

- Cytoskeletal gene list from Gene Ontology Browser (GO:0005856)

- Computational tools: R/Python with Limma package for normalization

Procedure:

- Data Retrieval: Obtain relevant transcriptome data from public repositories (see Table 1 for dataset examples).

- Batch Effect Correction: Address technical variations using the Limma package in R [11].

- Gene Filtering: Restrict analysis to cytoskeletal genes using Gene Ontology ID GO:0005856 (approximately 2,300 genes) [11].

- Feature Selection: Implement Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with SVM to identify the most discriminative genes:

- Utilize 5-fold cross-validation to assess feature importance

- Recursively remove features with the smallest weights

- Determine the optimal number of features that maximizes classification accuracy

- Data Partitioning: Split data into training (70-80%) and validation (20-30%) sets, maintaining class proportions.

Protocol 2: SVM Model Training and Optimization

Purpose: Develop and optimize an SVM classifier for high-dimensional biological data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Preprocessed gene expression data

- Computational environment: Python with scikit-learn or MATLAB

- High-performance computing resources for large-scale analysis

Procedure:

- Classifier Selection: Compare multiple algorithms (Decision Trees, Random Forest, k-NN, Gaussian Naive Bayes, SVM) using cross-validation accuracy.

- Kernel Selection: Evaluate linear, polynomial, and RBF kernels for specific dataset characteristics.

- Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Perform grid search with cross-validation for parameters C (regularization) and γ (kernel coefficient)

- Use stratified k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) to maintain class distributions

- Optimize for balanced accuracy, especially with imbalanced datasets

- Model Training: Train the final SVM model with optimized parameters on the complete training set.

- Model Validation: Assess performance on held-out test set using comprehensive metrics (accuracy, F1-score, recall, precision).

Protocol 3: Model Evaluation and Biomarker Validation

Purpose: Evaluate SVM classifier performance and validate identified biomarkers.

Materials and Reagents:

- Independent validation dataset(s)

- Statistical analysis software

- Visualization tools for ROC curves and performance metrics

Procedure:

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Compute accuracy, F1-score, recall, precision, and balanced accuracy

- Generate confusion matrix with True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), False Negatives (FN)

- Calculate Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV)

- ROC Analysis: Plot Receiver Operating Characteristic curves and calculate Area Under the Curve (AUC) values.

- External Validation: Apply trained model to completely independent datasets to assess generalizability.

- Biomarker Significance Testing: Conduct differential expression analysis on identified genes to confirm biological relevance.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare SVM performance against alternative machine learning approaches.

Application to Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

Case Study: Age-Related Disease Classification

Research has demonstrated SVMs' exceptional performance in classifying age-related diseases based on cytoskeletal gene expression patterns. A comprehensive study analyzing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), coronary artery disease (CAD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) revealed SVMs achieved the highest accuracy among multiple classifiers [11].

Table 1: Performance of SVM vs. Other Classifiers for Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

| Disease | DTs | RF | k-NN | SVM | GNB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | 89.15% | 91.04% | 92.33% | 94.85% | 82.17% |

| CAD | 87.90% | 92.21% | 91.50% | 95.07% | 90.07% |

| AD | 74.56% | 83.23% | 84.48% | 87.70% | 82.61% |

| IDCM | 87.63% | 94.05% | 94.93% | 96.31% | 81.75% |

| T2DM | 61.81% | 80.75% | 70.30% | 89.54% | 80.75% |

The SVM classifier consistently outperformed other methods across all disease classifications, demonstrating its particular suitability for high-dimensional cytoskeletal gene data [11].

Identified Cytoskeletal Gene Biomarkers

The application of RFE-SVM methodology identified specific cytoskeletal genes associated with each age-related disease, providing potential biomarkers for diagnosis and therapeutic targeting.

Table 2: Cytoskeletal Gene Biomarkers Identified by SVM for Age-Related Diseases

| Disease | Identified Genes | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|

| HCM | ARPC3, CDC42EP4, LRRC49, MYH6 | Actin polymerization, cytoskeletal organization, motor protein function |

| CAD | CSNK1A1, AKAP5, TOPORS, ACTBL2, FNTA | Kinase activity, scaffolding, ubiquitin ligase, cytoskeletal protein |

| AD | ENC1, NEFM, ITPKB, PCP4, CALB1 | Neuronal cytoskeleton, intermediate filaments, signaling |

| IDCM | MNS1, MYOT | Cytoskeletal structure, sarcomere organization |

| T2DM | ALDOB | Metabolic enzyme with cytoskeletal interactions |

These genes represent compelling candidates for further investigation as diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets in their respective age-related diseases [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SVM Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Datasets | Training and validation data | GEO Accession: GSE32453 (HCM), GSE113079 (CAD), GSE5281 (AD) |

| Cytoskeletal Gene List | Feature definition | Gene Ontology ID: GO:0005856 (~2,300 genes) |

| Normalization Tools | Data preprocessing | Limma Package (R) for batch effect correction |

| Feature Selection Algorithm | Dimensionality reduction | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with SVM |

| SVM Implementation | Model training | scikit-learn (Python) or MATLAB with optimization tools |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Model validation | Stratified 5-fold cross-validation |

| Performance Metrics | Model evaluation | ROC analysis, accuracy, F1-score, precision, recall |

Advanced SVM Applications and Methodological Considerations

Confounder-Correcting SVM (ccSVM)

Biological data often contains confounding variables such as population structure, age, gender, or experimental conditions that can distort classification results. The ccSVM approach addresses this by minimizing the statistical dependence between the classifier and confounding factors using the Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) [17].

The ccSVM optimization incorporates an additional term to standard SVM formulation: Minimize: ½∥w∥² + C∑ξᵢ + λ·tr(KHLH)

Where tr(KHLH) represents the HSIC measure between the reweighted kernel matrix K and side information kernel matrix L, H is a centering matrix, and λ controls the degree of confounder correction [17].

This approach has proven effective in diverse applications including tumor diagnosis across different laboratories and tuberculosis diagnosis across patient demographics, improving model generalizability and biological relevance.

Handling Class Imbalance

High-dimensional biological datasets frequently exhibit class imbalance, which can severely impact SVM performance. Effective strategies include:

- Applying class weights inversely proportional to class frequencies

- Using resampling techniques (SMOTE, undersampling, oversampling)

- Employing ensemble methods in conjunction with SVM

- Adjusting decision thresholds based on validation performance [16]

Workflow for Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

The following diagram illustrates the specific workflow for cytoskeletal gene classification using SVM in age-related disease research:

Support Vector Machines represent a powerful methodology for classifying high-dimensional biological data, particularly in the context of cytoskeletal gene expression in age-related diseases. The SVM protocol detailed in this technical note—encompassing rigorous data preprocessing, recursive feature selection, careful model training with cross-validation, and comprehensive evaluation—provides a robust framework for identifying biologically relevant gene signatures with diagnostic and therapeutic potential. The exceptional performance of SVMs in classifying age-related diseases based on cytoskeletal gene expression (achieving 87.70-96.31% accuracy across conditions) underscores their value in bioinformatics research and drug development pipelines.

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filamentous proteins, is fundamental to cellular integrity, shape, and intracellular transport. Comprising microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, this structure is indispensable for neuronal function, muscle contraction, and organelle trafficking [20]. mounting evidence establishes that the integrity of the cytoskeleton is intimately linked with the aging process and the pathogenesis of a spectrum of age-related diseases [11] [20]. Aging cells frequently exhibit a loss of cytoskeletal stability, which is associated with a decline in mitochondrial function and an accumulation of cellular damage [20]. This degradation contributes to the functional decline observed in neurodegenerative diseases, cardiomyopathies, and metabolic disorders.

The application of advanced computational methods, particularly Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers, has revolutionized the identification of cytoskeletal genes with critical roles in these pathologies. SVM models are exceptionally well-suited for analyzing high-dimensional genomic data due to their capacity to handle large feature spaces and identify complex, non-linear patterns [11] [12]. Recent research leveraging these models has pinpointed specific cytoskeletal genes, including ACTBL2, KIF5A, and MYH6, as being transcriptionally dysregulated in age-related diseases, highlighting their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets [11] [12]. This document details the experimental and computational protocols for validating the role of these genes, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Computational Identification via SVM-Based Classification

The discovery of ACTBL2, KIF5A, and MYH6 as key players was facilitated by a robust computational framework designed to analyze transcriptional changes in cytoskeletal genes across multiple age-related diseases.

Workflow for SVM-RFE Gene Selection

The following diagram illustrates the integrated machine learning and differential expression analysis pipeline used to identify key cytoskeletal genes.

SVM Model Performance and Selected Genes

The SVM-based model demonstrated superior performance in classifying disease states across multiple conditions, achieving the highest accuracy among five tested algorithms [11] [12]. The following table summarizes the model's performance and the key cytoskeletal genes identified for specific age-related diseases.

Table 1: SVM Classifier Performance and Identified Cytoskeletal Genes

| Age-Related Disease | SVM Accuracy | Key Cytoskeletal Genes Identified | Primary Cytoskeletal Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | 95.07% | ACTBL2, CSNK1A1, AKAP5, TOPORS, FNTA [12] | Actin polymerization, cytoskeletal organization [21] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | N/A | KIF5A, ALS2, DCTN1, PFN1, NF-L, NF-H [22] | Anterograde axonal transport, synaptic maintenance [22] [23] |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) | 94.85% | MYH6, ARPC3, CDC42EP4, LRRC49 [11] [12] | Sarcomeric motor protein, cardiac muscle contraction [11] |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 87.70% | ENC1, NEFM, ITPKB, PCP4, CALB1 [11] [12] | Neuronal structure, calcium signaling |

| Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM) | 96.31% | MNS1, MYOT [11] [12] | Sarcomeric and cytoskeletal integrity |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) | 89.54% | ALDOB [11] [12] | Cytoskeletal structure regulation |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Protocol 1: Functional Characterization of Actin Mutations

This protocol is adapted from studies on disease-causing actin mutations, such as those in ACTG2, which provide a template for investigating genes like ACTBL2 [24] [21].

1. Objectives:

- To express and purify wild-type and mutant actin proteins.

- To assess the impact of mutations on actin polymerization kinetics and filament stability using pyrene-actin assays.

- To visualize filament morphology and stability via negative stain electron microscopy.

2. Materials:

- Recombinant Protein Expression System: Human Expi293F cells [24].

- Affinity Purification Resin: Gelsolin segments 4-6 (G4G6) affinity column for Ca²⁺-dependent actin binding [24].

- Polymerization Assay Reagents: Purified actin (≥ 95% purity), 10X polymerization buffer (500 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM ATP, 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), pyrene-labeled actin [24].

- Equipment: Fluorometer, ultracentrifuge, fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system, electron microscope.

3. Procedure: 1. Protein Expression and Purification: - Transfect Expi293F cells with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutant (e.g., ACTBL2-mimetic) actin. - After 48-72 hours, harvest cells and lyse in a Ca²⁺-containing buffer. - Purify actin from the supernatant using a G4G6 affinity column. Elute with an EGTA-containing buffer to chelate Ca²⁺. - Dialyze the eluted actin into G-buffer (2 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM CaCl₂, pH 8.0). Determine concentration and store on ice for immediate use. 2. Pyrene-Actin Polymerization Assay: - Prepare a mixture of unlabeled actin (94%) and pyrene-labeled actin (6%) in G-buffer for a final concentration of 2 µM total actin. - Transfer the mixture to a quartz cuvette and place it in a fluorometer (excitation: 365 nm, emission: 407 nm). - Initiate polymerization by rapidly adding 1/10 volume of 10X polymerization buffer. Mix quickly and record fluorescence for 1-2 hours. - Calculate the polymerization rate from the slope of the initial linear increase and the critical concentration (Cc) from equilibrium fluorescence at varying actin concentrations. 3. Filament Stability Analysis: - For depolymerization assays, prepare polymerized actin filaments as above. - Dilute the pre-polymerized filaments 20-fold into G-buffer (final concentration 0.1 µM) to shift the system below the Cc. - Immediately monitor the decrease in pyrene fluorescence to determine the depolymerization rate.

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare the polymerization and depolymerization rates, as well as the Cc, of mutant versus wild-type actin. Mutations like R40C in ACTG2 cause sluggish polymerization, while R257C leads to rapid but unstable polymerization, indicating diverse pathogenic mechanisms [24].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Analysis of KIF5A-Dependent Axonal Transport

This protocol outlines a method for studying the functional consequences of KIF5A mutations observed in ALS [22] [23].

1. Objectives:

- To visualize and quantify mitochondrial motility in neurons derived from patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

- To assess the impact of KIF5A mutations on anterograde transport.

2. Materials:

- Cell Line: Human iPSCs from a healthy donor and an ALS patient with a known KIF5A mutation.

- Neuronal Differentiation Kit: Commercially available kits for motor neuron differentiation.

- Live-Cell Dyes: MitoTracker Red CMXRos for mitochondria.

- Imaging Equipment: Confocal microscope with a live-cell incubation chamber (maintaining 37°C and 5% CO₂).

- Software: Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with TrackMate plugin).

3. Procedure: 1. Motor Neuron Differentiation: - Differentiate iPSCs into motor neurons using a standardized protocol over 4-5 weeks. - Plate mature motor neurons on poly-D-lysine/laminin-coated glass-bottom dishes for imaging. 2. Live-Cell Imaging of Mitochondrial Transport: - On day in vitro (DIV) 14, load neurons with 50 nM MitoTracker Red in pre-warmed culture medium for 30 minutes. - Replace with fresh medium and equilibrate the dish in the live-cell chamber for 15 minutes. - Acquire time-lapse images of neuronal axons every 5-10 seconds for a total of 10 minutes using a 60x oil immersion objective. 3. Quantification of Transport: - Export movies as TIFF stacks and analyze using TrackMate. - Manually define a region of interest (ROI) encompassing a straight axon segment. - The software will track individual mitochondria, generating data for velocity, track length, and directionality. - Categorize mitochondria as anterograde (moving away from the soma), retrograde (towards the soma), or stationary.

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare the percentage of mitochondria undergoing anterograde transport and their mean velocity between KIF5A-mutant and control motor neurons. A significant reduction is indicative of impaired KIF5A function, a known hallmark of ALS pathophysiology [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Gene and Protein Functional Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Expi293F Cell System | High-efficiency protein expression for difficult-to-express proteins like actins. | Recombinant expression of wild-type and mutant ACTBL2/ACTG2 for biochemical assays [24]. |

| G4G6 Affinity Column | Ca²⁺-dependent purification of native, functional actin. | Isolation of pure, polymerization-competent actin from cell lysates [24]. |

| Pyrene-Labeled Actin | Fluorescent reporter for real-time monitoring of actin polymerization kinetics. | Pyrene-actin polymerization assay to determine polymerization rates and critical concentration [24]. |

| Human iPSCs | Generation of patient-specific disease models for neurodegenerative and cardiac diseases. | Differentiation into motor neurons to study KIF5A mutations in ALS or cardiomyocytes to study MYH6 in HCM [22]. |

| MitoTracker Dyes | Live-cell staining of mitochondria for tracking organelle dynamics. | Visualization and quantification of axonal transport deficits in KIF5A-mutant neurons [23]. |

| CRISPR/Cpf1 System | Precise gene editing for creating knockout or knock-in models. | Generation of isogenic control and mutant iPSC lines to study the specific effects of a point mutation [25]. |

Integrated Pathway and Logical Workflow

The relationship between cytoskeletal gene mutations, their functional consequences, and the resulting disease phenotypes is complex. The following pathway diagram synthesizes this information for ACTBL2, KIF5A, and MYH6.

The integration of SVM-based computational classification with rigorous experimental validation provides a powerful strategy for pinpointing cytoskeletal genes like ACTBL2, KIF5A, and MYH6 as critical factors in age-related diseases. The protocols outlined here for biochemical characterization and cellular functional analysis offer a roadmap for researchers to validate the role of these and other candidate genes. Furthermore, the identified genes and their pathways present promising targets for therapeutic development. For instance, stabilizing the cytoskeleton with targeted compounds has been proposed as a potential strategy to counteract aging and degenerative processes [20]. Continued research in this field, leveraging the described tools and methods, will deepen our understanding of cytoskeletal biology in aging and accelerate the development of novel diagnostics and treatments.

The integration of cytoskeleton biology with machine learning represents a transformative approach in genomic medicine. This protocol details the application of Support Vector Machines (SVM) for classifying cytoskeletal gene signatures in age-related diseases. The cytoskeleton, comprising dynamic filamentous proteins, maintains cellular integrity and organization, with dysregulation implicated in numerous pathological states. SVM learning excels at identifying subtle patterns in high-dimensional genomic data, making it ideally suited for discerning disease-specific cytoskeletal gene expression signatures. We present a standardized computational framework that leverages Recursive Feature Elimination with SVM to identify minimal yet informative cytoskeletal gene sets that accurately discriminate between patient and normal samples across five age-related diseases, achieving area under the curve (AUC) values up to 0.99 in validation studies.

The cytoskeleton is a network of intracellular filamentous proteins that forms an organized structural framework essential for cellular shape, integrity, motility, and intracellular transport [11]. Comprising microfilaments (actin filaments), intermediate filaments, and microtubules, this dynamic structure connects the cell to its external environment and ensures proper spatial organization of cellular contents [12]. Decades of research have established that cytoskeletal dysregulation is associated with downstream signaling events that regulate cellular activity, aging, and neurodegeneration [11].

The molecular interplay between cytoskeletal components and disease pathophysiology presents both a challenge and opportunity for genomic medicine. The complexity of cytoskeletal gene networks— comprising over 2,300 genes by Gene Ontology classification (GO:0005856) — necessitates advanced computational approaches for meaningful analysis [11] [26]. Support Vector Machine learning offers particular advantages for this domain, as it can identify delicate patterns in complex, high-dimensional datasets and effectively handle the large feature spaces typical of genomic data [27].

This protocol establishes a standardized methodology for applying SVM to classify cytoskeletal genes in age-related diseases, enabling researchers to identify robust biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets through a reproducible computational framework.

Theoretical Foundation

Cytoskeletal Genes in Age-Related Diseases

Cytoskeletal integrity is essential for diverse cellular processes, including intracellular trafficking and phagocytosis [11]. When cytoskeletal dynamics or organization become altered, the consequences manifest in diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegeneration [12]. Specifically, research has revealed that:

- Defects in cytoskeletal proteins result in myopathies through altered signaling and structural mechanisms [11]

- Microtubule defects in axons cause defective axonal transport, contributing to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease (AD) [11]

- Memory loss may be attributed to microtubule depolymerization [11] [12]

- In Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) patients, proteins involved in cytoskeletal structure are significantly altered [11]

- Multiple genetic variants in genes involved in cytoskeletal assembly regulation have been identified in Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) patients [12]

SVM Fundamentals and Biological Applicability

Support Vector Machines represent a powerful classification approach based on statistical learning theory [28]. The fundamental principle involves finding optimal hyperplanes that separate data categories with maximal margins, which confers superior generalization performance compared to other classifiers [27].

Table 1: SVM Performance Comparison Across Classifiers for Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

| Disease | Decision Tree | Random Forest | k-NN | Gaussian Naive Bayes | SVM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | 89.15% | 91.04% | 92.33% | 82.17% | 94.85% |

| CAD | 87.90% | 92.21% | 91.50% | 90.07% | 95.07% |

| AD | 74.56% | 83.23% | 84.48% | 82.61% | 87.70% |

| IDCM | 87.63% | 94.05% | 94.93% | 81.75% | 96.31% |

| T2DM | 61.81% | 80.75% | 70.30% | 80.75% | 89.54% |

The theoretical basis for SVM's superiority in cytoskeletal gene classification stems from several inherent advantages [27]:

- Capacity Control: SVM's margin maximization provides protection against overfitting, crucial for genomic data with thousands of features but limited samples

- Nonlinear Mapping: Kernel functions enable SVM to handle non-linear relationships in gene expression data without explicit feature transformation

- Robustness: SVM maintains performance despite high-dimensional data where features far exceed samples

- Convex Optimization: The learning algorithm guarantees finding global minima, unlike neural networks which may converge to local minima

Experimental Design and Workflow

The integrated workflow combines feature selection, machine learning classification, and differential expression analysis to identify cytoskeletal genes with diagnostic potential for age-related diseases.

Dataset Specifications

Table 2: Transcriptome Datasets for Cytoskeletal Gene Analysis in Age-Related Diseases

| Disease | GEO Accession | Patient Samples | Control Samples | Cytoskeletal Genes Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | GSE32453, GSE36961 | 114 | 44 | 1,696 |

| CAD | GSE113079 | 93 | 48 | 1,989 |

| AD | GSE5281 | 87 | 74 | 1,561 |

| IDCM | GSE57338 | 82 | 136 | 2,167 |

| T2DM | GSE164416 | 39 | 18 | 2,188 |

Application Notes: Protocols and Procedures

Protocol 1: Cytoskeletal Gene Compilation

Purpose: To establish a comprehensive reference set of cytoskeletal genes for subsequent analysis.

Materials:

- Gene Ontology Browser (amigo.geneontology.org)

- Computational environment (R/Python)

- Gene annotation databases

Procedure:

- Access the Gene Ontology Browser using term ID GO:0005856

- Extract all human genes annotated with the "cytoskeleton" cellular component term

- Verify gene symbols against current HGNC nomenclature

- Export the complete gene list (approximately 2,304 genes) as a reference set

- Categorize genes by cytoskeletal components: microfilaments, intermediate filaments, microtubules

Technical Notes:

- The compiled gene set should include polymeric filamentous structures with long-range order within the cell [26]

- Regular updates are recommended as GO annotations evolve

- Cross-reference with MSigDB "CYTOSKELETON" gene set (M457) for verification [26]

Protocol 2: SVM-RFE for Cytoskeletal Feature Selection

Purpose: To identify minimal yet informative cytoskeletal gene signatures that discriminate disease states.

Materials:

- Normalized gene expression matrices

- Python scikit-learn or R e1071 packages

- High-performance computing resources for iterative modeling

Procedure:

- Initialize SVM classifier with linear kernel

- Set RFE to eliminate one feature per iteration (small steps enhance accuracy)

- For each iteration:

- Rank features by SVM weights

- Eliminate lowest-ranked feature(s)

- Retrain SVM with remaining features

- Record cross-validation accuracy

- Identify the feature subset yielding peak cross-validation performance

- Validate selected features on holdout or external datasets

Technical Notes:

- Linear kernels often outperform complex kernels with genomic data [27]

- For datasets with >100 samples, consider eliminating 5-10% of features per iteration to reduce computation time

- Always stratify cross-validation folds to preserve class distribution

Protocol 3: Differential Expression Integration

Purpose: To integrate statistically significant differentially expressed genes with RFE-SVM selected features.

Materials:

- Raw count data from RNA-seq or normalized microarray data

- DESeq2 package (RNA-seq) or Limma package (microarrays)

- Multiple testing correction procedures

Procedure:

- Perform differential expression analysis using appropriate methods:

- For RNA-seq: DESeq2 with thresholds of |log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05

- For microarrays: Limma with moderated t-tests and Benjamini-Hochberg correction

- Subset results to cytoskeletal genes from Protocol 1

- Identify overlapping genes between RFE-selected features and differentially expressed cytoskeletal genes

- Prioritize genes consistent across both selection methods for experimental validation

Technical Notes:

- Batch effects significantly impact differential expression results; always include batch correction when combining datasets

- For hypothesis generation, consider relaxing thresholds to |log2FC| > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.1

- Functional enrichment analysis of overlapping genes provides biological validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cytoskeletal Gene Classification

| Category | Resource | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Sets | GO:0005856 | 2,304 cytoskeletal genes from Gene Ontology | Reference set for feature selection [26] |

| Transcriptome Data | GEO Datasets | Public repository of expression data | Model training and validation [11] |

| Normalization Tools | Limma Package | Batch effect correction and normalization | Preprocessing of multi-dataset studies [11] |

| Feature Selection | RFE-SVM | Recursive Feature Elimination with SVM | Identifies minimal discriminative gene sets [11] |

| Classification Algorithms | SVM with linear kernel | Maximal margin classifier | Core learning method for gene expression data [27] |

| Validation Metrics | ROC Analysis | Receiver Operating Characteristic curves | Performance assessment on external data [11] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2/Limma | Statistical analysis of expression changes | Identifies significantly dysregulated genes [11] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The molecular relationship between cytoskeletal genes and disease processes involves complex signaling interactions that can be captured through SVM classification of expression patterns.

Validation and Performance Metrics

Classification Performance Across Diseases

The SVM-RFE framework demonstrates robust performance across multiple age-related diseases, achieving high predictive accuracy with minimal feature sets.

Table 4: Performance Metrics of SVM-RFE Classifiers for Cytoskeletal Genes

| Disease | Selected Features | Accuracy | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | 4 (ARPC3, CDC42EP4, LRRC49, MYH6) | 96.25% | 95.70% | 96.10% | 95.40% | 0.99 |

| CAD | 5 (CSNK1A1, AKAP5, TOPORS, ACTBL2, FNTA) | 95.74% | 95.30% | 95.90% | 94.80% | 0.98 |

| AD | 5 (ENC1, NEFM, ITPKB, PCP4, CALB1) | 90.06% | 89.50% | 90.20% | 88.90% | 0.94 |

| IDCM | 2 (MNS1, MYOT) | 97.25% | 97.10% | 97.50% | 96.70% | 0.99 |

| T2DM | 1 (ALDOB) | 92.98% | 92.60% | 93.10% | 92.20% | 0.95 |

Biological Validation Through Differential Expression

Integration with differential expression analysis confirms the biological relevance of SVM-selected cytoskeletal genes:

- For Alzheimer's disease, identified genes (ENC1, NEFM) are established neuronal cytoskeletal components with known roles in neurodegeneration [11]

- In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, MYH6 encodes a sarcomeric protein central to cardiac muscle contraction [11] [12]

- Cross-disease analysis reveals shared cytoskeletal genes (ANXA2, TPM3, SPTBN1) suggesting common pathological mechanisms across age-related conditions [12]

Concluding Remarks

The integration of cytoskeleton biology with SVM machine learning establishes a powerful paradigm for genomic medicine. This protocol provides a standardized framework for identifying disease-specific cytoskeletal gene signatures with diagnostic and therapeutic potential. The SVM-RFE approach consistently identifies minimal yet highly discriminative gene sets across diverse age-related diseases, achieving exceptional classification performance while mitigating overfitting.

Future applications could expand to single-cell transcriptomics, spatial genomics, and integration with proteomic data, further illuminating the complex relationship between cytoskeletal dynamics and human disease. The reproducibility and robustness of this protocol enable systematic investigation of cytoskeletal gene networks across the spectrum of human pathology, accelerating biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

From Data to Diagnosis: Implementing SVM-RFE for Cytoskeleton Gene Signature Identification

Within the framework of research focused on classifying cytoskeletal genes using Support Vector Machines (SVM), the initial and most critical phase involves the robust acquisition and processing of transcriptomic data. Cytoskeletal genes, which are essential for cellular structure, motility, and division, are often implicated in a range of age-related diseases [12]. The reliability of any subsequent computational classification, including the identification of potential biomarkers, is fundamentally dependent on the quality and integrity of the input gene expression data [29]. This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide for sourcing and processing raw RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) data from public repositories, preparing it for downstream differential expression analysis and machine learning applications. The workflow outlined herein is designed to be beginner-friendly, enabling researchers to generate standardized count matrices from raw sequencing files, which can then be utilized to train SVM models for cytoskeletal gene classification [12] [30].

Data Acquisition from Public Repositories

The first step is to identify and download relevant transcriptomic datasets from public archives. Several key repositories host data suitable for cytoskeletal gene research.

Table 1: Key Public Repositories for Transcriptomic Data

| Repository Name | Data Type | Key Features | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [31] | Bulk & Single-Cell RNA-Seq | NIH-funded; vast repository; interfaces with SRA for raw data. | Primary source for diverse disease-specific datasets. |

| EMBL Expression Atlas [31] | Bulk & Single-Cell RNA-Seq | High-level annotations; categorizes studies as "baseline" or "differential". | Finding pre-annotated studies with specific experimental conditions. |

| TCGA [31] | Bulk RNA-Seq (Cancer) | Focused on human cancer; linked to clinical data. | Research on cytoskeletal genes in oncogenesis and cancer progression. |

| Recount3 [31] | Bulk RNA-Seq | Uniformly processed data from GEO, SRA, and TCGA. | Obtaining analysis-ready data without raw file processing. |

To locate datasets pertinent to cytoskeleton research, such as those related to neurodegeneration or cardiomyopathy, use the advanced search functions of these databases. Search terms might include "cytoskeleton," "actin," "microtubule," along with specific diseases like "Alzheimer's" or "Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy" [12]. Upon identifying a relevant study (e.g., via its GEO accession number, such as GSE123467), the raw sequencing data in the form of FASTQ files can be downloaded, typically from the associated SRA Run Selector [31].

A Step-by-Step Protocol for RNA-Seq Data Processing

This section details a computational workflow to process raw FASTQ files into a gene count matrix, which serves as the input for differential expression analysis and SVM classification.

Software Installation and Setup

The pipeline utilizes a combination of command-line tools and R packages. The simplest way to install the required command-line software is via the Conda package manager [29].

Quality Control and Read Trimming

Begin by assessing the quality of the raw sequencing files using FastQC [29]. This tool generates reports on read quality scores, sequence duplication levels, and adapter contamination. Following quality assessment, use Trimmomatic to remove low-quality sequences, adapter content, and other impurities.

Read Alignment and Quantification

The trimmed reads are then aligned to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using the HISAT2 aligner [29]. The resulting Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) files are converted to their binary format (BAM) and sorted using Samtools. Finally, the featureCounts tool (from the Subread package) is used to generate the count matrix by counting the number of reads mapped to each gene.

The final output, gene_counts.csv, is a table where rows represent genes and columns represent samples, containing the raw read counts for each gene in each sample.

Differential Expression Analysis in R

The gene count matrix is imported into R/RStudio for statistical analysis. The DESeq2 package is commonly used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between experimental conditions (e.g., disease vs. control) [29]. The following steps are performed:

- Data Import: Load the count data and associated sample metadata into a DESeqDataSet object.

- Normalization and Modeling: DESeq2 internally normalizes for library size and RNA composition and fits a negative binomial generalized linear model to the data.

- DEG Identification: Extract results to obtain a list of genes with their log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values.

Genes with a significant adjusted p-value (e.g., padj < 0.05) and a substantial fold change are considered differentially expressed. This list of DEGs can be filtered for cytoskeletal genes (e.g., using Gene Ontology ID GO:0005856) to create a targeted dataset for SVM classification [12].

Visualization for Quality Assessment

Visualization is an indispensable step for verifying the quality of the data and the appropriateness of the statistical models before proceeding to classification [32]. Two highly effective methods are:

- Parallel Coordinate Plots: These plots display each gene as a line across the samples. In a well-controlled experiment, replicates should show flat, consistent lines, while distinct patterns or crossings should be visible between different treatment groups. This helps visualize the overall structure of differential expression [32].

- Scatterplot Matrices: This method plots read count distributions across all samples. Data points (genes) are expected to cluster tightly along the x=y line in scatterplots between replicates, while showing more spread in plots between different conditions, confirming higher between-group variability [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomic Data Processing

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Conda | Package and environment manager. | Simplifies installation and dependency management for all command-line bioinformatics tools [29]. |

| FastQC | Quality control tool for high-throughput sequence data. | Generates initial reports on raw FASTQ file quality [29]. |

| Trimmomatic | Flexible read trimming tool. | Removes adapters and low-quality bases to improve alignment accuracy [29]. |

| HISAT2 | Fast and sensitive alignment program. | Maps sequencing reads to the reference genome [29]. |

| featureCounts | Efficient program for counting reads to genomic features. | Generates the final gene count matrix from aligned reads [29]. |

| DESeq2 | R package for differential analysis of count data. | Identifies statistically significant differentially expressed genes [29]. |

| ARCHS4 | Web resource with pre-processed RNA-seq data. | Allows quick access to uniformly processed gene expression matrices from public studies for preliminary analysis [31]. |

Workflow Diagrams

SVM Classification Workflow for Cytoskeletal Genes

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE-SVM) Methodology for Optimal Cytoskeleton Gene Selection

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filamentous proteins, is fundamental to cellular integrity, shape, and intracellular transport. Transcriptional dysregulation of cytoskeletal genes is increasingly implicated in the pathology of numerous age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes [12] [11]. Identifying the specific cytoskeletal genes involved is crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets. However, the high-dimensional nature of genomic data—where the number of genes (features) vastly exceeds the number of samples—presents a significant analytical challenge. This Application Note details a robust computational protocol employing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) coupled with Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification to optimally select cytoskeletal genes with high diagnostic and prognostic value from transcriptomic data.

The RFE-SVM pipeline for cytoskeleton gene selection integrates dataset preparation, machine learning-based feature selection, and biomarker validation into a cohesive workflow. The following diagram outlines the key stages of this methodology.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Phase 1: Data Acquisition and Curation

Objective: To compile a high-quality dataset of cytoskeletal genes and disease-specific transcriptomic profiles.

Step 1: Define the Cytoskeletal Gene Universe

- Retrieve the canonical list of cytoskeletal genes from the Gene Ontology (GO) Browser using the accession ID GO:0005856 [12] [11]. This list encompasses genes encoding microfilaments, intermediate filaments, microtubules, and associated regulatory proteins. As of the 2025 study, this list contained 2,304 genes [12]. The complete list should be archived as a reference (e.g., Supplementary Table S1).

Step 2: Source Disease Transcriptome Data

- Access public gene expression repositories such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The table below provides examples of datasets used in prior research for various age-related diseases [11].

Step 3: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Perform background correction and normalization using appropriate packages for the platform (e.g., the

affypackage in R for Affymetrix data, or thelimmapackage for other array types) [12] [33]. - Address batch effects across multiple datasets using the ComBat method or similar functions within the

limmapackage to ensure data integration is valid [12] [11]. - Map probe IDs to official gene symbols, averaging expression values for probes corresponding to the same gene.

- Perform background correction and normalization using appropriate packages for the platform (e.g., the

Phase 2: RFE-SVM Model Training and Feature Selection

Objective: To iteratively refine the feature set to a minimal number of cytoskeletal genes that optimally discriminate between disease and control samples.

Step 1: Initialize the Model

- Subset the normalized expression matrix to include only the 2,304 cytoskeletal genes.

- Partition the data into training and hold-out test sets (e.g., 70/30 or 80/20 split).

Step 2: Configure and Run the RFE-SVM Algorithm

- Use a Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a linear kernel as the core classifier. SVMs are particularly suited for high-dimensional genomic data due to their effectiveness in handling large feature spaces [12] [11].

- Implement the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) process as a wrapper around the SVM. This is a backward selection method that works as follows [12] [34]:

- Train the SVM model using the current set of features.

- Compute the feature importance. For a linear SVM, this is typically the absolute value of the weight coefficient (

coef_) for each feature. - Rank all features based on their computed importance.

- Remove the least important feature(s) (e.g., the bottom 10% or a fixed number per iteration).

- Repeat steps 1-4 with the reduced feature set until a predefined stopping criterion is met.

Step 3: Define Stopping Criteria

Phase 3: Validation and Biomarker Identification