Quantifying Microtubule Orientation: From Light Microscopy to Advanced Imaging in Cellular Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies and tools for quantifying microtubule orientation, a critical parameter in cell biology with implications for neuronal development, disease research, and drug...

Quantifying Microtubule Orientation: From Light Microscopy to Advanced Imaging in Cellular Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies and tools for quantifying microtubule orientation, a critical parameter in cell biology with implications for neuronal development, disease research, and drug discovery. We explore foundational principles of microtubule dynamics and polarity, detail established and emerging quantification techniques including fluorescence microscopy, polarized light imaging, and computational analysis tools. The content addresses common methodological challenges and optimization strategies, while providing a framework for validating and comparing results across different experimental conditions. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust microtubule orientation analysis in their investigations.

Microtubule Dynamics and Orientation: Fundamental Principles for Quantitative Analysis

Microtubules are intrinsically polarized cytoskeletal filaments, with a fast-growing plus end and a slow-growing minus end. This structural asymmetry, known as microtubule polarity, is a fundamental property that governs intracellular transport, cell division, and cell morphology. In neurons, the precise orientation of microtubules dictates the directional movement of motor proteins like kinesins and dyneins, which in turn ensures the targeted delivery of cargo to specific cellular compartments such as axons or dendrites. The organization of microtubule networks is not static; it is developmentally regulated and can be influenced by environmental cues, including light. This guide provides a comparative analysis of microtubule orientation, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers investigating cytoskeletal dynamics in both neuronal and plant systems.

Core Principles of Microtubule Polarity

Microtubules serve as polarized tracks for intracellular transport. Their organization varies significantly between cell types:

- In axons, microtubules exhibit a uniform polarity, with their plus ends oriented distal to the cell body [1] [2].

- In dendrites of mammalian neurons, microtubules have a mixed polarity, with approximately half oriented plus-end-out and the other half minus-end-out [1] [2].

- This mixed organization in dendrites is established during development. Initially, all neurites have uniform plus-end-out microtubules. As the neuron matures and dendrites differentiate, minus-end-out microtubules are incorporated, achieving the final, balanced non-uniform array [2].

The polarity of microtubules is more than just a structural detail; it is a key architectural principle that enables polarized sorting by different motor proteins [1].

Experimental Methods for Determining Microtubule Polarity

motor-PAINT: Super-Resolution Polarity Mapping

motor-PAINT is a single-molecule imaging technique that enables super-resolution mapping of microtubule structures and their absolute polarity orientation [1].

Table: Key Steps in the motor-PAINT Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation | Culture and plate cells (e.g., COS7, U2OS, or rat hippocampal neurons). | Cell culture media, substrates |

| 2. Cytoskeleton Extraction & Fixation | Permeabilize cells with detergent and fix with paraformaldehyde. | Detergent (e.g., Triton X-100), Paraformaldehyde (PFA) |

| 3. Motor Protein Incubation | Apply purified, fluorescently labeled plus-end-directed kinesin motors. | DmKHC-GFP (or similar recombinant kinesin) |

| 4. Real-Time Imaging | Image transient binding and movement of single motor molecules. | TIRF or HILO microscope, imaging buffer |

| 5. Data Analysis | Use single-molecule tracking and localization algorithms to reconstruct microtubule paths and polarity. | Tracking software (e.g., TrackMate), custom analysis scripts |

This protocol successfully preserves microtubule organization, allowing motors to run for hundreds of nanometers along the fixed cytoskeleton. The resulting trajectories are used to generate a diffraction-unlimited image where the orientation of every microtubule is known. The method achieves a lateral resolution of approximately 52 ± 5 nm (mean ± SD), sufficient to resolve individual microtubules in dense networks [1].

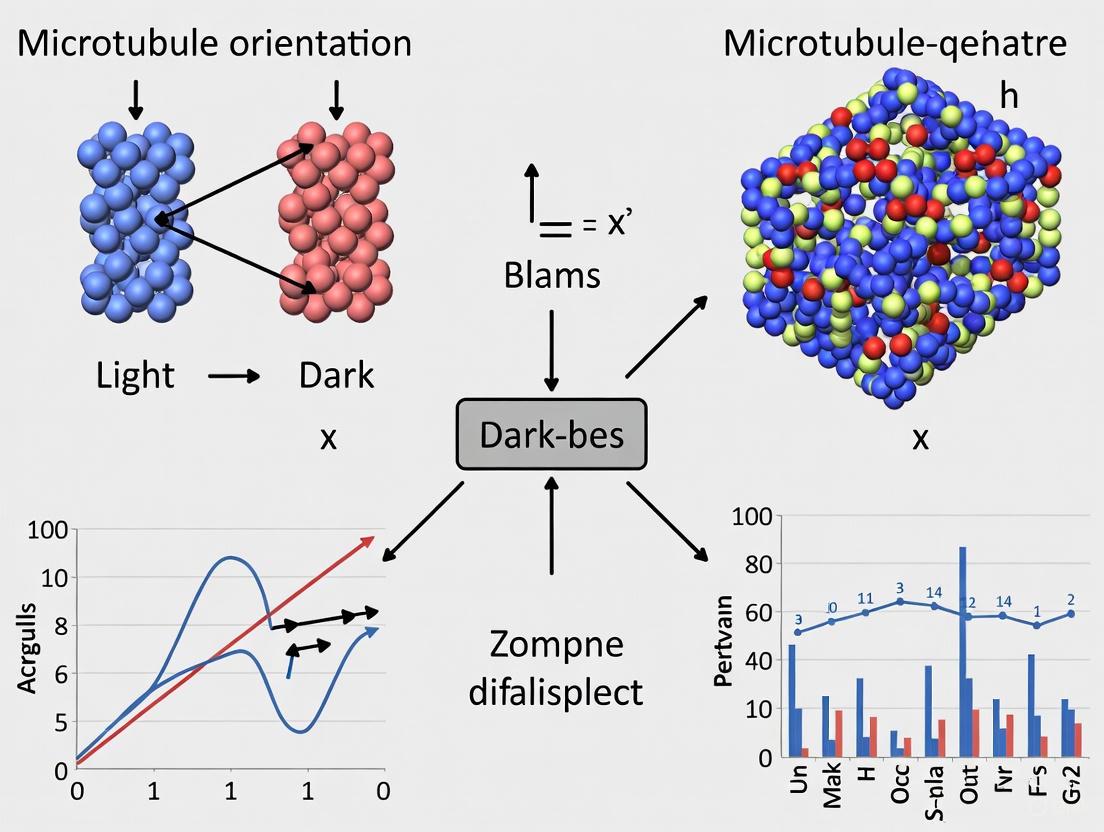

Figure: motor-PAINT experimental workflow for super-resolution microtubule polarity mapping.

Polarity Analysis via Markers of Stability

An alternative, indirect method to infer microtubule organization involves analyzing post-translational modifications of tubulin, which correlate with microtubule age and stability.

- Stable microtubules are often marked by acetylation and detyrosination [3].

- Dynamic microtubules are predominantly tyrosinated [3].

In dendrites, these modifications are segregated by orientation: stable, acetylated microtubules are predominantly oriented minus-end-out, while dynamic, tyrosinated microtubules are mostly plus-end-out [1]. Immunofluorescence staining for these markers can therefore provide insights into the underlying polarity patterns.

Comparative Data: Microtubule Orientation and Function

Polarity and Stability in Neuronal Processes

The following table summarizes key differences in microtubule properties between axons and dendrites.

Table: Microtubule Polarity and Stability in Neurons

| Feature | Axon | Dendrites |

|---|---|---|

| Microtubule Polarity | Uniformly plus-end-out [1] [2] | Mixed (approx. 50/50 plus- and minus-end-out) [1] [2] |

| Microtubule Stability | High stability in the shaft [3] | Variable stability based on orientation [1] |

| Key Markers | Enriched in acetylated & detyrosinated tubulin [3] | Acetylated tubulin on minus-end-out MTs; Tyrosinated tubulin on plus-end-out MTs [1] |

| Developmental Onset | Established early and maintained [2] | Mixed polarity emerges during differentiation [2] |

Motor Protein Specificity and Cargo Sorting

Different motor proteins recognize specific microtubule subsets, enabling polarized cargo transport.

Table: Motor Protein Specificity in Neurons

| Motor Protein | Direction | Preferred Microtubule Subset | Transport Destination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | Plus-end-directed | Stable, acetylated microtubules [1] | Axon-selective [1] |

| Kinesin-3 | Plus-end-directed | Dynamic, tyrosinated microtubules [1] | Both axons and dendrites [1] |

This specificity explains why the plus-end-directed Kinesin-1 is excluded from dendrites: in dendrites, its preferred track (acetylated microtubules) is oriented minus-end-out, so engaging with it directs cargo toward the cell body, not into the dendrite [1]. In contrast, Kinesin-3 prefers tyrosinated microtubules, which in dendrites are predominantly plus-end-out, allowing it to drive anterograde transport into dendrites [1].

Microtubule Polarity in Light-Dark Research Contexts

While neuronal microtubule polarity is not directly regulated by light, research in plant systems reveals a profound influence of light signaling on microtubule organization and dynamics, offering parallel insights for cytoskeletal biologists.

Light Control of Microtubule Organization in Plants

In plants, light perceived by photoreceptors like phytochrome B (phyB) triggers signaling cascades that reorganize the cortical microtubule (CMT) array [4] [5].

- In darkness, CMTs in hypocotyls and cotyledons are arranged transversely to the growth axis, reinforcing lateral walls and promoting longitudinal elongation [4].

- Upon light exposure, CMTs reorient to a more longitudinal array, which restricts longitudinal elongation and promotes lateral expansion, leading to shorter, rounder morphology [4].

This light-driven microtubule rearrangement is mediated by the phyB-PIF-LNG pathway [4]:

- Light-activated phyB translocates to the nucleus and induces the degradation of PIF transcription factors.

- The downregulation of PIFs leads to reduced expression of LONGIFOLIA (LNG) genes, which encode microtubule-associated proteins.

- Reduced LNG levels promote the reorientation of microtubules from transverse to longitudinal.

Figure: Light signaling controls microtubule organization and growth patterns in plants.

High-Intensity Light and Microtubule Depolymerization

Recent evidence shows that very high-intensity light can disrupt microtubule dynamics across cell types. Prolonged exposure to high-intensity white light induces a sharp rise in intracellular Ca²⁺ release from the endoplasmic reticulum via IP3R channels. The elevated calcium concentration leads to microtubule depolymerization, dispersing organelles that rely on microtubules for transport [6]. This effect has been observed in fish chromatophores, HeLa, and HEK293T cells [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Microtubule and Polarity Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| Nocodazole | Microtubule-destabilizing agent; promotes depolymerization [3] [6] | Testing microtubule dynamics and stability; validating polarity assays [1] |

| Taxol/Paclitaxel | Microtubule-stabilizing agent; suppresses dynamics [3] [6] | Probing the role of stability in cellular processes like polarization [3] |

| Anti-Acetylated Tubulin | Antibody recognizing a post-translational modification of stable microtubules [3] | Immunostaining to identify long-lived, stable microtubule subsets [1] [3] |

| Anti-Tyrosinated Tubulin | Antibody recognizing a mark of newly assembled, dynamic microtubules [3] | Immunostaining to identify dynamic microtubule subsets [1] [3] |

| Recombinant Kinesin (e.g., DmKHC) | Purified, fluorescently labeled motor protein for in vitro assays [1] | Core component of the motor-PAINT technique for super-resolution polarity mapping [1] |

| BAPTA-AM | Cell-permeable calcium chelator [6] | Investigating calcium-dependent processes in microtubule regulation [6] |

| 2-APB | Inhibitor of IP3 receptor (IP3R) on the ER [6] | Blocking Ca²⁺ release from internal stores to study downstream effects on microtubules [6] |

The Biological Significance of Microtubule Orientation in Cellular Function

Microtubules are fundamental components of the cytoskeleton, functioning as polarized polymers that serve as structural scaffolds, intracellular transport highways, and key players in cell morphogenesis and division. These hollow cylindrical structures, typically composed of 13 protofilaments arranged in a head-to-tail arrangement of α/β-tubulin heterodimers, exhibit an intrinsic structural polarity with a fast-growing plus-end and a slow-growing minus-end [7] [8]. This structural asymmetry is not merely a biochemical curiosity but rather a fundamental property that dictates their biological functionality. The precise organization and orientation of microtubules within cells are critical for establishing cell polarity, directing intracellular transport, guiding cell division, and shaping cellular morphology [7] [9]. In specialized cells such as neurons, epithelial cells, and plant cells, the strategic arrangement of microtubule arrays enables the execution of complex cellular functions essential for tissue development and organismal viability.

Recent advances in live-cell imaging and genetic manipulation have revealed that microtubule orientation is dynamically regulated in response to both intrinsic signaling pathways and environmental cues. Light-mediated signaling in plants, for instance, directly influences microtubule organization to control photomorphogenic responses such as hypocotyl elongation and cotyledon expansion [4] [5]. Similarly, in migrating cells and developing neurons, the reorientation of microtubule arrays establishes front-rear polarity and directional growth capacity [10] [11]. This comparative guide examines the mechanisms and functional consequences of microtubule orientation across biological systems, with particular emphasis on experimental approaches for quantifying these phenomena under varying environmental conditions.

Comparative Analysis of Microtubule Orientation Patterns Across Biological Systems

Table 1: Microtubule Orientation Patterns and Functional Significance in Different Cell Types

| Cell Type/System | Microtubule Orientation Pattern | Primary Regulatory Mechanisms | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Hypocotyl Cells | Dark: Transverse to growth axis; Light: Shifts to longitudinal | Phytochrome signaling; Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs); Light quality | Controls directional cell expansion; Light inhibits elongation, promotes radial expansion [4] [5] |

| Neuronal Axons | Mature: ~95% plus-end-out; Immature: Mixed (50-80% plus-end-out) | Selective stabilization; Dynein-mediated sliding; Augmin-mediated templating; Anti-catastrophe factors (e.g., p150) | Enables efficient long-distance intracellular transport; Establish neuronal polarity [10] [9] |

| Fibroblasts/Mesenchymal Cells | Radial array from centrosome toward cell periphery | Centrosomal nucleation; Microtubule dynamics | Facilitates cell migration; Organelle positioning; Intracellular transport [7] [8] |

| Epithelial Cells | Apical-basal axis with minus-ends anchored near cell-cell contacts | Non-centrosomal nucleation; Ninein and PLEKHA7 anchoring | Establishes cell polarity; Directs vesicle transport along apical-basal axis [8] |

| T-cells | Centrosomal nucleation with reorientation during immune synapse formation | Microtubule length optimization; Dynein activity | Polarizes secretory machinery toward target cell; Enables directed cytokine release [12] |

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Microtubule Growth Parameters in Different Systems

| Parameter | Neuronal Axons (D. melanogaster) | Plant Cells (A. thaliana) | General Eukaryotic Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plus-end Growth Rate | Variable by orientation and position | Modified by light signaling | 1-10 µm/min (dynamic instability) [7] [10] |

| Catastrophe Frequency | Lower for plus-end-out MTs in distal axon (especially with p150) | Affected by light/gibberellin pathway | Variable; regulated by MAPs and cellular conditions [10] [5] |

| Growth Length/Cycle | Plus-end-out: 2.11 µm; Minus-end-out: 1.39 µm (within 10µm of tip) | Not specified | Highly variable based on cell type and conditions [10] |

| Half-life | Several minutes (dynamic) | Not specified | Minutes to hours; stabilized by MAPs [7] |

| Key Regulatory Proteins | p150, dynein, augmin, TRIM46 | Phytochromes, PIFs, LNG proteins, MAPs | γ-TuRC, MAP2, Tau, DCX, +TIPs [4] [10] [9] |

Experimental Approaches for Microtubule Orientation Quantification

Live-Cell Imaging Methodologies

The quantification of microtubule orientation and dynamics has been revolutionized by live-cell imaging approaches that enable real-time visualization of microtubule behavior in living systems. The most widely employed methodology involves fluorescent protein tagging of microtubule-associated proteins that specifically mark growing microtubule ends or the microtubule lattice itself [10] [5].

EB1-GFP imaging represents a particularly powerful approach for analyzing microtubule dynamics and orientation. EB1 (End Binding 1) is a conserved protein that specifically binds to growing microtubule plus ends, forming characteristic "comets" that track the direction and extent of microtubule polymerization [10]. In practice, neurons or other cells expressing EB1-GFP are imaged using time-lapse confocal microscopy, with images captured at regular intervals (typically 2-10 seconds) over several minutes. The resulting movies are then processed to generate kymographs or analyzed using specialized computational tools such as KymoButler to automatically track comet trajectories, velocity, and growth distances [10]. This approach enables researchers to simultaneously determine both the orientation of individual microtubules (based on comet direction) and their dynamic instability parameters (growth speed, catastrophe frequency, etc.).

For plant systems studying light-dark transitions, researchers have employed complementary genetic strategies to circumvent the confounding effects of imaging light on photomorphogenic responses. These include using long-hypocotyl mutants (phyB, hy1), PIF5 overexpressors, and exogenous gibberellin application to maintain elongation growth under microscope observation conditions [5]. Such approaches have revealed that microtubules undergo defined sequences of realignment during growth initiation, including the formation of a transitional "microtubule star" configuration that marks the onset of rapid elongation [5].

Computational Analysis and Modeling

Quantitative analysis of microtubule orientation extends beyond simple visual assessment to encompass sophisticated computational approaches. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV), adapted from fluid dynamics, has been employed to map the flow patterns of numerous EB1-GFP comets simultaneously, revealing large-scale organization principles within microtubule arrays [5]. This method can identify domains of coordinated microtubule polarity and transitions between different array configurations.

Stochastic modeling and computer simulations have proven invaluable for integrating multiple mechanisms that regulate microtubule orientation. For neuronal axons, modeling approaches have incorporated parameters such as differential catastrophe rates based on orientation, dynein-mediated microtubule sliding, and augmin-mediated microtubule nucleation to generate testable predictions about how uniform plus-end-out orientation emerges during development [10]. Similarly, in plant systems, computational modeling has helped elucidate how light signaling influences microtubule dynamics and reorientation capability [5].

Signaling Pathways Regulating Microtubule Orientation

Light Signaling Pathways in Plants

In plant systems, light quality and intensity serve as master regulators of microtubule orientation, thereby influencing growth patterns and morphological development. The phytochrome photoreceptor system mediates these responses through a well-defined molecular pathway [4].

Diagram 1: Plant light signaling pathway regulating microtubules.

Phytochromes exist in two photoconvertible forms: the red light-absorbing Pr form and the far-red light-absorbing Pfr form. Upon activation by red light, phytochrome (primarily phyB) converts to the Pfr form and translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with and promotes the degradation of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors (PIFs) [4]. In darkness, PIFs accumulate and promote elongation growth through mechanisms that include microtubule reorganization. The recent work by Cho and Choi (2025) has identified LONGIFOLIA genes (LNG1 and LNG2) as critical downstream effectors of this pathway that directly influence microtubule organization [4]. These microtubule-associated proteins promote transverse microtubule arrays that facilitate longitudinal cell expansion, with their expression being repressed by light-activated phytochrome signaling.

Microtubule Orientation Establishment in Neurons

The establishment of uniform microtubule orientation in neuronal axons involves a complex interplay of several mechanisms that collectively bias the network toward plus-end-out configuration [10].

Diagram 2: Neuronal microtubule orientation mechanisms.

Research in Drosophila neurons has revealed that selective stabilization of plus-end-out microtubules plays a particularly important role. Plus-end-out microtubules exhibit significantly lower catastrophe rates in the distal axon, resulting in more persistent growth compared to their minus-end-out counterparts [10]. This stabilization is mediated in part by the anti-catastrophe factor p150, which is enriched in the distal axon tip. Additionally, cytoplasmic dynein transports short minus-end-out microtubules toward the cell body, effectively clearing them from the axon [10]. Meanwhile, augmin-mediated nucleation generates new microtubules that typically inherit the orientation of their parent microtubules, reinforcing the existing polarity bias. The combined action of these mechanisms progressively establishes the highly polarized microtubule array essential for efficient axonal transport.

Research Reagent Solutions for Microtubule Orientation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microtubule Orientation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Microtubule Markers | EB1-GFP, GFP-Tubulin, mCherry-Tubulin | Live visualization of microtubule dynamics and orientation | EB1-GFP labels growing plus-ends; GFP-Tubulin labels entire microtubule lattice [10] [5] |

| Microtubule-Targeting Drugs | Nocodazole, Taxol/Paclitaxel, Colchicine | Modulate microtubule dynamics/polymerization | Nocodazole destabilizes; Taxol stabilizes; Used for mechanistic perturbation [7] [10] [12] |

| Genetic Tools | Phytochrome mutants (phyA, phyB), PIF mutants/overexpressors, LNG mutants | Dissect specific pathways in plant systems | Enable study of light signaling without confounding light effects [4] [5] |

| Genetic Tools | p150 knockdown, DCX knockout, Tau knockout | Investigate neuronal microtubule regulation | Reveal roles of specific MAPs in orientation establishment [10] [9] |

| Specialized Cell Lines | Drosophila primary neurons, Arabidopsis GFP-marked lines, Jurkat T-cells | Provide cell-type specific models | Drosophila neurons allow live imaging of MT dynamics; Plant lines enable light-dark studies [4] [10] [12] |

| Analysis Tools | KymoButler, PIV software, Stochastic modeling platforms | Quantify dynamics and orientation from image data | Automated analysis improves throughput and objectivity [10] [5] |

Implications for Human Health and Disease

The precise regulation of microtubule orientation has profound implications for human health, particularly in the contexts of neurodegenerative disease and cancer therapeutics. In neurons, disrupted microtubule polarity impairs the efficient transport of essential components over vast distances, contributing to the pathogenesis of conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [10] [9] [13]. The maintenance of uniform plus-end-out microtubule orientation is crucial for sustaining the delivery of mitochondria, synaptic components, and survival factors from the cell body to distant synaptic terminals. Defects in this system result in "traffic jams" that compromise neuronal function and viability.

Microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs) represent a clinically important class of compounds that exploit the essential role of microtubules in cell division. These include microtubule-stabilizing drugs like taxanes and destabilizing agents such as vinca alkaloids [7] [13]. While traditionally employed as anti-cancer therapies, there is growing interest in applying these compounds to neurological conditions. The therapeutic challenge lies in achieving selective effects on target cells while minimizing disruption to post-mitotic neurons, where microtubule orientation is critical for maintained function. Next-generation MTAs with improved specificity for particular tubulin isotypes or enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration offer promising avenues for addressing these challenges [13].

In brain malignancies such as glioblastoma, cancer cells frequently exhibit alterations in microtubule organization that contribute to uncontrolled proliferation and invasive behavior [13]. The γ-tubulin ring complex, which normally orchestrates proper microtubule nucleation, is often dysregulated in tumor cells, leading to aberrant microtubule formation and chromosomal instability. Understanding how microtubule orientation is perturbed in these pathological states may inform the development of more targeted therapeutic approaches that specifically exploit these abnormalities while sparing normally functioning cells.

Core Principles and Quantitative Parameters of Dynamic Instability

Microtubules are fundamental components of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, characterized by their non-equilibrium behavior known as dynamic instability. This process describes the stochastic alternation of individual microtubules between phases of growth and shrinkage, allowing them to rapidly reorganize in response to cellular needs [14]. This dynamic behavior is not merely a random process but is intrinsically regulated by the biochemical and structural properties of tubulin itself, and is further modulated by a suite of cellular factors to meet specific physiological requirements [14] [15].

The core mechanism driving dynamic instability centers on GTP hydrolysis. Tubulin heterodimers assemble into the microtubule in a GTP-bound state. Following incorporation into the polymer, the GTP bound to β-tubulin is hydrolyzed to GDP, inducing a conformational change in the tubulin dimer that strains the lattice [14] [15]. A growing microtubule is thought to be stabilized by a GTP-cap, a terminal region of unhydrolyzed GTP-tubulin that protects the structure from disassembly. The loss of this cap triggers a transition to the shrinking phase [14]. Recent evidence suggests this process is complex; the growing phase involves multiple substates of increasing instability (a phenomenon called "aging"), and the shrinkage phase is not uniform but can slow down over time [16].

The table below summarizes the key quantitative parameters that define dynamic instability, as observed in in vitro reconstitution experiments with pure tubulin.

Table 1: Key Parameters of Microtubule Dynamic Instability (In Vitro)

| Parameter | Description | Quantitative Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Speed of tubulin dimer addition. | Concentration-dependent; similar for all microtubules under given conditions [14]. |

| Shortening Rate | Speed of tubulin dimer loss. | Several-fold faster than growth; highly variable across microtubules and can slow down over time [14] [16]. |

| Catastrophe Frequency | Transition frequency from growth to shrinkage. | Increases with microtubule "age"; a multistep process [14] [16]. |

| Rescue Frequency | Transition frequency from shrinkage back to growth. | Stochastic; potentially linked to GTP-tubulin patches within the microtubule lattice [14]. |

Experimental Approaches for Quantifying Dynamic Instability

A range of sophisticated microscopy techniques has been developed to visualize and quantify the dynamics of individual microtubules in living cells and in vitro. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations regarding resolution, invasiveness, and experimental context.

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Studying Microtubule Dynamics

| Method | Experimental Workflow | Key Applications & Data Output |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Analog Cytochemistry | 1. Purify tubulin protein.2. Covalently label with a fluorophore (e.g., X-rhodamine).3. Microinject labeled tubulin into living cells.4. Image using low-light level time-lapse fluorescence microscopy [17]. | Visualizing individual microtubule dynamics in thin cellular regions (e.g., lamella). Measures growth/shrinkage rates and transition frequencies [17]. |

| Video-Enhanced Differential Interference Contrast (VE-DIC) Microscopy | 1. Culture cells on glass coverslips.2. Observe unstained cells using a DIC microscope.3. Apply electronic contrast enhancement and background subtraction to video signal.4. Track microtubule ends in real time [17]. | Non-invasive, continuous recording of microtubule behavior in thin cellular regions. Allows highly accurate measurement of dynamic instability parameters without photobleaching concerns [17]. |

| In Vitro Reconstitution Assays | 1. Purify tubulin from brain tissue or recombinant sources.2. Polymerize microtubules in a controlled biochemical environment.3. Use TIRF or other microscopy to image dynamics.4. Analyze kinetics following catastrophe [16]. | Investigating intrinsic tubulin properties without cellular complexity. Identified phenomena such as shrinkage slowdown [16]. |

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for quantifying microtubule dynamic instability, integrating key steps from fluorescence microscopy, VE-DIC, and in vitro approaches.

Regulation of Dynamics in Cellular Contexts: Light as a Model Signal

Within cells, the intrinsic dynamic instability of microtubules is precisely modulated by signaling pathways to direct cell morphology and growth. Research in plants has elegantly demonstrated how light signaling pathways ultimately converge on the cytoskeleton to reorient growth, providing a quantifiable model for how external signals regulate microtubule dynamics.

In Arabidopsis, light perception by phytochrome photoreceptors (e.g., phyB) initiates a signaling cascade that controls hypocotyl and cotyledon expansion. The activated phytochrome translocates to the nucleus and induces the degradation of PIF transcription factors, which are key promoters of elongation in darkness [4]. This pathway directly influences microtubule organization. In dark-grown hypocotyls, cortical microtubules are arranged transversely to the growth axis, reinforcing lateral walls and promoting rapid longitudinal elongation. Upon light exposure, this array reorients to a more longitudinal direction, inhibiting elongation and promoting lateral expansion [4] [5].

A recent study links this pathway directly to microtubule-associated proteins. The LONGIFOLIA (LNG) genes, which encode microtubule-associated proteins, were identified as downstream targets of the phyB-PIF module. PIFs promote LNG expression in the dark, and LNG proteins are necessary to maintain transverse microtubule arrays that facilitate polar elongation. Light, via phyB, represses PIF activity, thereby downregulating LNG expression and allowing microtubules to reorient, which reshapes the cotyledon from oval to round [4]. Furthermore, light signaling has been shown to directly alter microtubule dynamics; mutants in the light/GA pathway (e.g., phyB) exhibit faster microtubule polymerization rates and more rapid array reorientations, explaining their faster elongation rates [5].

Figure 2: The phytochrome-PIF signaling pathway links light perception to microtubule organization and directional growth. Solid lines indicate established steps from the search results; dashed lines indicate connections to other hormonal pathways mentioned.

Conversely, high-intensity light can disrupt microtubules through a separate, more direct mechanism. Studies on fish xanthophores and human cell lines (HeLa, HEK293T) showed that prolonged exposure to high-intensity light triggers a massive release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum via IP3 receptors. The resulting spike in intracellular Ca²⁺ leads to microtubule depolymerization and consequent dispersion of organelles, independent of the transcriptional signaling pathways used for low-light morphogenesis [6].

Table 3: Comparative Regulation of Microtubule Dynamics by Light Conditions

| Condition | Signaling Pathway | Effect on Microtubules | Cellular Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darkness | PIFs active → LNG expression high. | Transverse cortical arrays stabilized. | Polar (longitudinal) cell elongation. |

| Low-Intensity Light | Phytochrome active → PIFs degraded → LNG low. | Reorientation from transverse to longitudinal arrays. | Inhibition of elongation; lateral expansion. |

| High-Intensity Light | IP3R-mediated Ca²⁺ release from ER. | Ca²⁺-induced depolymerization of microtubules. | Dispersion of organelles; potential cell damage. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Microtubule Dynamics Research

The following table catalogues key reagents used in the experiments cited herein, providing a resource for researchers designing studies on dynamic instability.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Microtubule Dynamics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| X-rhodamine / Tetramethylrhodamine-tubulin | Fluorescently labeled tubulin for visualization. | Microinjection into cells for time-lapse fluorescence microscopy of microtubule dynamics [17]. |

| EB1-GFP | Plus-end binding protein marking growing microtubule ends. | Live-cell imaging of microtubule polymerization trajectories and array organization [5]. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Microtubule-stabilizing agent. | Used to suppress dynamic instability; stabilizes microtubules against depolymerization [6]. |

| Nocodazole | Microtubule-depolymerizing agent. | Used to disrupt microtubule networks; induces depolymerization [6]. |

| BAPTA-AM | Cell-permeable calcium chelator. | Used to buffer intracellular Ca²⁺ and investigate its role in signaling to microtubules [6]. |

| 2-APB (2-Aminoethyl diphenylborinate) | Inhibitor of IP3 receptor Ca²⁺ channels. | Used to block Ca²⁺ release from the endoplasmic reticulum [6]. |

| Phytochrome Mutants (e.g., phyB) | Disruption of specific light signaling pathways. | Used to dissect the role of specific photoreceptors in controlling microtubule organization and cell growth [4] [5]. |

Polarized light microscopy (PLM) has been an indispensable tool in cell biology, providing the foundation for discovering and quantifying microtubule orientation and dynamics. This guide compares PLM with modern imaging alternatives, framing the discussion within research on microtubule behavior under varying environmental conditions, such as light and dark.

Technique Evolution and Historical Significance

Polarized light microscopy exploits the birefringent properties of anisotropic materials. Microtubules, as ordered molecular structures, are birefringent—meaning they split light into two perpendicular components that travel at different velocities [18] [19]. In a polarized light microscope, light first passes through a polarizer, becoming plane-polarized. When this light interacts with a birefringent specimen like a microtubule, the component vibrations are resolved into privileged directions, ordinary and extraordinary wavefronts. After exiting the specimen, these out-of-phase light waves are recombined by an analyzer (a second polarizer), generating interference patterns that reveal the specimen's orientation and order [18].

This principle made PLM a cornerstone for early microtubule research. For decades, it was the primary method for observing the organization of cytoskeletal structures without staining. A key application was studying the reorientation of microtubules in plant cells in response to light and dark conditions. Research showed that light inhibition of shoot elongation is linked to how the light/gibberellin-signaling pathway affects microtubule properties, influencing their polymerization and ability to reorient [5]. This provided crucial historical data on how external stimuli translate into cellular shape changes.

Technique Comparison: PLM vs. Modern Alternatives

The table below summarizes how traditional polarized light microscopy compares to contemporary methods for studying microtubules.

Table 1: Comparison of Microscopy Techniques for Microtubule Studies

| Technique | Key Principle | Best for Microtubule Studies | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM) [18] [19] [20] | Detects birefringence of ordered structures using crossed polarizers and an analyzer. | Visualizing global orientation and alignment of dense, ordered microtubule arrays. | Cannot resolve single microtubules; lower resolution (~250 nm); difficult to confirm lamellarity. |

| Fluorescence Microscopy [20] | Uses fluorescent probes (e.g., GFP-tubulin) to tag specific structures. | Imaging microtubule localization, dynamics, and turnover in live cells. | Photobleaching; phototoxicity can alter microtubule dynamics [5]; dye can cause artifacts. |

| Confocal Microscopy [20] | Uses a pinhole to eliminate out-of-focus light, creating sharp optical sections. | Generating 3D reconstructions of the microtubule network in thicker samples. | Lower definition for small vesicles/oligolamellar structures; can be slower. |

| Electron Microscopy (EM) [20] | Uses an electron beam for ultrastructural imaging. | Visualizing individual microtubules, protofilament structure, and precise spatial relationships. | Requires extensive sample preparation (fixing, staining); cannot image live cells. |

| Polarized Light-Sheet Microscopy (Modern Hybrid) [21] | Combines polarized light with dual-view light-sheet microscopy (diSPIM). | Simultaneously imaging the full 3D position and orientation of molecules in living cells. | Complex instrumentation and data reconstruction; emerging technology. |

The "Polarized Light-Sheet Microscope" represents a modern evolution, merging the orientation-sensing strength of PLM with the high-resolution, optical-sectioning capabilities of light-sheet microscopy [21]. This hybrid addresses a key historical limitation of traditional PLM: the inability to efficiently illuminate samples with polarized light along the direction of light propagation. Its dual-view design allows sensing polarized fluorescence much more effectively, enabling volumetric imaging of 3D orientation in cellular structures like mitotic spindles [21].

Experimental Protocols: From Classic to Contemporary

Protocol: Observing Microtubule Orientation with PLM

This classic protocol is used to assess microtubule alignment in fixed tissue or cells [5] [18].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Strain-Free Objective and Condenser: Essential to avoid spurious birefringence from the microscope optics themselves [18].

- Polarizer and Analyzer: The core components for generating and analyzing polarized light. The polarizer is typically fixed, while the analyzer can be moved in and out of the light path [18].

- Circular Rotating Stage: A 360-degree graduated stage is critical for orienting the specimen and measuring angles of birefringence [18] [19].

- Compensators/Retardation Plates: Inserts placed between the polarizers to enhance optical path differences and determine the slow and fast axes of the specimen [18].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Fix plant tissue (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana hypocotyls) or cultured cells. Microtubules can be stained for correlative imaging, but their innate birefringence is the target for PLM.

- Microscope Setup: Configure the polarized light microscope with crossed polarizers (polarizer and analyzer at 90 degrees), resulting in a dark background.

- Imaging: Place the sample on the stage. Rotate the stage to observe changes in brightness. Maximum brightness occurs when the microtubule's longitudinal axis is at a 45-degree angle to the polarization planes.

- Data Collection: Record birefringence patterns and intensity. Use stage rotation angles to quantify the predominant orientation of microtubule arrays in the sample.

Protocol: Quantifying 3D Microtubule Orientation with Polarized Light-Sheet Microscopy

This modern protocol details the method used in the 2025 study for volumetric orientation imaging [21].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Dual-View Light-Sheet Microscope (diSPIM): The core platform providing two orthogonal illumination and imaging paths [21].

- Liquid Crystals: Integrated into the diSPIM to allow precise control of the input polarization direction [21].

- Fluorescently-Labeled Proteins (e.g., GFP-tubulin): Used to tag microtubules in living cells.

- Computational Reconstruction Algorithms: Custom software is required to process the dual-view, multi-polarization data and reconstruct the full 3D orientation and position of molecules [21].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Culture living cells expressing fluorescently labeled tubulin.

- Microscope Setup: The sample is mounted in the diSPIM, where it can be illuminated from two perpendicular directions by thin sheets of polarized light. The polarization direction is controlled via liquid crystals.

- Data Acquisition: For each viewpoint, images are acquired at different input polarization angles. This process is repeated as the sample is scanned to build a volumetric dataset.

- Image Reconstruction and Analysis: Advanced algorithms merge the dual-view data and extract the orientation of the fluorescent dipoles from the polarized fluorescence measurements. This computationally generates a map of the full 3D orientation (not just position) of the microtubules within the volume [21].

Experimental Data and Findings

Research using these techniques has yielded critical quantitative data on microtubule behavior.

Table 2: Experimental Findings on Microtubule Dynamics from Light Microscopy

| Experimental Context | Key Finding | Technique Used | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light/Dark Response in Plants [5] | Light inhibits microtubule polymerization rates and slows reorientation. Mutants in light-signaling pathways show faster reorientation. | Polarized light microscopy; EB1-GFP imaging. | Explains the antagonistic effects of light/dark on plant cell elongation. |

| High-Intensity Light Effect [6] | Prolonged high-intensity light (≥40 min, 10,000 lux) induces microtubule depolymerization, dispersing organelles. | Pharmacological assays (Paclitaxel, Nocodazole). | Reveals a light-intensity-dependent mechanism that disrupts cytoskeleton-based transport. |

| Reactive Microglia Remodeling [22] | Microtubules reorganize into a stable, radial array driven by Cdk1, facilitating cytokine release. | Proteomics, immunofluorescence, morphology segmentation. | Links microtubule reorganization to functional changes in immune cells. |

| 3D Orientation Mapping [21] | New microscope can simultaneously image the full 3D orientation and position of molecules in living cells. | Hybrid polarized light-sheet microscope (diSPIM). | Enables tracking of 3D protein orientation changes, revealing previously hidden biology. |

Signaling Pathways in Microtubule Response to Light

The cellular response to light that leads to microtubule rearrangement involves specific signaling cascades, as elucidated by pharmacological and genetic studies.

Microtubules are fundamental components of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, performing essential functions in intracellular transport, cell division, and maintenance of cell shape. These dynamic polymers are composed of αβ-tubulin heterodimens that undergo continual assembly and disassembly through a process known as dynamic instability. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing microtubule dynamics is crucial for both basic cell biology research and drug development, particularly in areas such as neurodegenerative diseases and cancer therapeutics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key molecular players—tubulin dimers, GTP caps, and regulatory proteins—focusing on their distinct characteristics, experimental measurements, and functional relationships under varying cellular conditions, including light-dark cycles that influence cytoskeletal organization.

Tubulin Dimers: Structural Foundations and Dynamic Properties

Tubulin dimers form the basic building blocks of microtubules. Each dimer consists of α- and β-tubulin subunits, which assemble head-to-tail to form protofilaments that subsequently associate laterally to form the hollow microtubule cylinder. The intrinsic properties of these dimers fundamentally influence microtubule dynamics and stability.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Tubulin Dimers and Their Isoforms

| Property | αβ-Tubulin Heterodimer | Class III β-Tubulin | β1-Tubulin (Class VI) | BtubA/B (Bacterial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Heterodimer, ~50 kDa per subunit | Neuronal-specific β-tubulin isoform | Most divergent amino acid sequence | Homolog with similarity to both α- and β-tubulin |

| Stability | Kd = 84 nM (54-123 nM) for dimer dissociation [23] | Binds colchicine more slowly than other β-isotypes [24] | Disrupts microtubule network when expressed in mammalian cells [24] | Chaperone-free folding, weak dimerization [24] |

| Polymerization | GTP-dependent, forms 13-protofilament microtubules | Incorporated into neuronal microtubules | Forms marginal-band-like structures in platelets [24] | Forms 4-5 protofilament "mini-microtubules" [24] |

| Localization | Ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells | Exclusively in neurons [24] | Megakaryocytes and platelets [24] | Prosthecobacter bacteria [24] |

| Functional Significance | Core structural unit of microtubules | Popular neuronal identifier [24] | Important for platelet formation [24] | Evolutionary relationship to eukaryotic tubulin unclear [24] |

The monomer-dimer equilibrium of tubulin is a crucial regulatory point in microtubule assembly. Recent biophysical studies using sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation and fluorescence anisotropy have quantified the dissociation constant (Kd) of rat brain αβ-tubulin at approximately 84 nM (range 54-123 nM), demonstrating reversible dissociation with moderately fast kinetics (koff range 10⁻³-10⁻² s⁻¹) [23]. This dynamic equilibrium allows cells to rapidly adjust the pool of available dimers for microtubule polymerization in response to cellular signals.

Tubulin isotype diversity further contributes to the functional specialization of microtubules. For example, class III β-tubulin is exclusively expressed in neurons and serves as a specific identifier for nervous tissue, while β1-tubulin (class VI) plays a specialized role in platelet formation [24]. The existence of these isoforms, along with various post-translational modifications, allows for fine-tuning of microtubule properties in different cell types and subcellular compartments.

Experimental Analysis: Tubulin Dimer Dynamics

Methodology: The reversible dissociation of tubulin dimers into monomers has been characterized using sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) and fluorescence anisotropy (FA) [23]. In these experiments, rat brain tubulin is purified and fluorescently labeled with dyes such as DyLight-488 or DyLight-550. SV experiments are conducted at 50,000 rpm and 20°C, monitoring either absorbance (230 nm or 280 nm) or fluorescence. Global analysis combining sedimentation velocity and fluorescence anisotropy data enables precise determination of thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.

Key Findings: These studies reveal that tubulin dimers reversibly dissociate with a Kd of approximately 84 nM, and the monomeric form remains stable for several hours. The dissociation kinetics occur with koff values in the range of 10⁻³-10⁻² s⁻¹. This reversible equilibrium is not significantly affected by solution changes involving GTP/GDP, urea, or trimethylamine oxide, indicating remarkable stability in the monomer-monomer association [23].

GTP Caps: Molecular Determinants of Microtubule Stability

The GTP cap model has served as the prevailing explanation for microtubule dynamic instability for almost four decades. According to this model, a protective "cap" of GTP-bound tubulin dimers at the growing microtubule end stabilizes the structure, while loss of this cap triggers a switch to rapid depolymerization (catastrophe).

Table 2: GTP-Cap Properties and Regulatory Influences

| Parameter | Plus End Dynamics | Minus End Dynamics | EB Protein Modulation | Stabilized (GMPCPP) Microtubules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Fast | Slow | Linear scaling with tubulin concentration [25] | Not applicable |

| GTP-Cap Size | Larger at high tubulin concentrations | Smaller than plus ends | Reduced size with increased EB concentration [25] | Permanent GTP-like cap |

| Catastrophe Frequency | High at low tubulin concentrations | Low despite slow growth | Increased frequency [25] | No catastrophe |

| Stabilization Mechanism | GTP-tubulin incorporation balanced with hydrolysis | Structural differences in end configuration | Preferential binding to GTP-tubulin lattice [25] | Non-hydrolyzable GTP analog |

| EB Comet Length | Up to 600 nm at high tubulin concentrations [25] | Shorter than plus ends | Decreased length with higher Mal3 concentration [25] | Not applicable |

The size of the GTP cap is determined by the balance between the rate of GTP-tubulin incorporation at the growing end and the rate of GTP hydrolysis within the incorporated dimers. Faster-growing microtubules therefore tend to possess larger GTP caps, making them more resistant to catastrophe. Recent studies using EB proteins as markers for GTP caps have confirmed that the cap size increases linearly with microtubule growth rate, reaching lengths of 600 nm or more at high tubulin concentrations [25].

Interestingly, microtubule minus ends exhibit lower catastrophe frequencies despite having smaller GTP caps and slower growth rates compared to plus ends [25]. This observation challenges the simple correlation between GTP-cap size and stability, suggesting that additional structural factors contribute to microtubule resilience. The structural conformation of the microtubule end, including the arrangement of curved versus straight protofilaments, may play a crucial role in determining stability beyond the nucleotide content alone.

Experimental Analysis: GTP-Cap Visualization and Measurement

Methodology: GTP-caps can be visualized and measured using End-Binding (EB) proteins as molecular markers. EB proteins autonomously recognize growing microtubule ends and form characteristic comet-shaped distributions that decay exponentially along the microtubule lattice. In vitro reconstitution assays involve purifying EB proteins (such as human EB1 or fission yeast Mal3) and tubulin, then monitoring their interaction using TIRF microscopy. The length and intensity of EB comets serve as proxies for GTP-cap dimensions under various conditions [25].

Key Findings: EB comet size scales linearly with microtubule growth rate over a range of tubulin concentrations. Catastrophe frequency exhibits a sharp decrease as EB-comet size increases, becoming negligible for comets larger than 300 nm (equivalent to approximately 40 tubulin layers) [25]. High-temporal resolution studies reveal that EB proteins are gradually lost from microtubule ends prior to catastrophe events, supporting the protective function of the GTP-cap. Interestingly, increasing concentrations of EB proteins can decrease comet length and increase catastrophe frequency, suggesting that EBs may accelerate GTP hydrolysis and thus reduce the effective GTP-cap size [25].

Regulatory Proteins: Orchestrators of Microtubule Dynamics

A diverse array of regulatory proteins fine-tunes microtubule dynamics by interacting with tubulin dimers, modifying microtubule ends, or stabilizing/destabilizing the microtubule lattice. These proteins allow cells to adapt microtubule behavior to specific physiological requirements.

Table 3: Microtubule Regulatory Proteins and Their Functions

| Regulatory Protein | Category | Primary Function | Effect on Dynamics | Cellular Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPPP/p25 | Microtubule-Associated Protein (MAP) | Promotes microtubule bundling and nucleation [26] | Stabilization, enhanced acetylation | Oligodendrocyte differentiation, myelination [26] |

| Stathmin | Tubulin dimer-binding protein | Sequesters tubulin dimers [27] | Increased catastrophe frequency | Cell division, signal transduction |

| EB1 | Plus-End Tracking Protein (+TIP) | Master organizer of +TIPs, GTP-cap sensor [25] | Modulates growth and catastrophe | All eukaryotic cells |

| Kinesin-13 (MCAK) | Microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin | Accelerates transition to catastrophe [27] | Destabilization | Mitosis, chromosome segregation |

| Tau | Microtubule-Associated Protein (MAP) | Stabilizes microtubules, spacing between filaments [27] | Stabilization, reduced dynamics | Neurons, axon stability |

| XMAP215 | Microtubule polymerase | Promotes tubulin incorporation [27] | Increased growth rate | Cell division, cytoplasmic organization |

| GSK-3β | Signaling kinase | Phosphorylates MAPs, regulating their activity [27] | Context-dependent stabilization/destabilization | Multiple signaling pathways |

TPPP/p25 represents a particularly interesting regulatory protein with context-dependent functions. This intrinsically disordered protein promotes microtubule bundling, enhances tubulin acetylation by inhibiting deacetylases, and functions as a powerful nucleator of microtubules at Golgi outposts in oligodendrocytes—essential for proper myelination [26]. Pathologically, TPPP/p25 forms toxic oligomers with α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease and Multiple System Atrophy, highlighting the importance of regulated expression levels.

The LONGIFOLIA (LNG) proteins demonstrate how microtubule-associated proteins can integrate environmental signals with cytoskeletal organization. In plants, LNG proteins promote transverse microtubule arrangements that support longitudinal cell expansion downstream of phytochrome B and PIF signaling, linking light perception to directional growth through microtubule orientation [4].

Experimental Analysis: Regulatory Protein Functions

Methodology: The functions of microtubule-associated proteins like TPPP/p25 are typically characterized through a combination of in vitro reconstitution assays and cellular studies. Purified proteins are incubated with tubulin to assess effects on polymerization kinetics, bundling, and nucleation using light scattering assays and electron microscopy. Cellular localization is determined by transfection with fluorescently tagged constructs followed by live-cell imaging or fixed immunofluorescence. Functional significance is established through knockdown or knockout approaches, such as TPPP/p25 silencing in oligodendrocyte precursor cells, which impedes differentiation and disrupts microtubule nucleation from Golgi outposts [26].

Key Findings: TPPP/p25 knockout mice exhibit hypomyelination with shorter, thinner myelin sheaths, along with breeding and motor coordination deficits [26]. Live-cell imaging reveals that TPPP/p25 interaction with microtubules is dynamic, with altered localization during cell division—dissociating from most microtubules during mitosis while accumulating on spindle microtubules and centrosomes [26]. These findings demonstrate how regulatory proteins can undergo cell cycle-dependent redistribution to coordinate microtubule functions with cellular events.

Integrated Signaling Pathways Regulating Microtubule Dynamics

Microtubule dynamics are integrated with cellular signaling networks that respond to both internal cues and external stimuli. Two particularly well-characterized pathways involve light-sensitive mechanisms in plant and animal cells.

Diagram 1: Light-Mediated Microtubule Regulation Pathways. Two distinct light-sensing pathways regulate microtubule organization. High-intensity light triggers Ca²⁺ release via IP3 receptors, causing microtubule depolymerization. In plants, red light activates phytochrome B, leading to PIF degradation and derepression of LONGIFOLIA proteins that reorganize microtubules.

Experimental Analysis: Light-Induced Microtubule Rearrangement

Methodology: The effects of light on microtubule organization have been investigated using both animal chromatophore models and plant systems. In xanthophores of the large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea), high-intensity white light (HIWL) exposure at 10,000 lux for >40 minutes induces pigment dispersion through microtubule depolymerization [6]. Pharmacological approaches using inhibitors (2-APB for IP3 receptors, BAPTA-AM for calcium chelation) and microtubule stabilizers (paclitaxel) help identify signaling components. In plants, phytochrome mutants (phyA, phyB) and PIF overexpression lines are used to dissect signaling pathways connecting light perception to microtubule reorganization during cotyledon expansion [4].

Key Findings: HIWL-induced microtubule depolymerization results from extraordinary high levels of intracellular Ca²⁺ released from IP3R channels in the endoplasmic reticulum [6]. This mechanism is conserved from fish chromatophores to human cell lines (HeLa, HEK293T). In plants, the phyB-PIF-LNG pathway controls microtubule rearrangement from transverse to longitudinal orientations, directing growth directionality during cotyledon expansion [4]. These findings demonstrate how diverse environmental signals converge on microtubule regulators to orchestrate cellular responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Microtubule Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | Key Functional Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Probes | [¹¹C]MPC-6827 | PET imaging of destabilized microtubules [28] | High specificity for destabilized MTs, excellent brain uptake |

| GFP-Tubulin | Live-cell imaging of microtubule dynamics | Fluorescent tagging of microtubule network | |

| Chemical Modulators | Paclitaxel | Microtubule stabilization studies [6] | Promotes microtubule assembly, prevents depolymerization |

| Nocodazole | Microtubule depolymerization assays [6] | Binds β-tubulin, disrupting microtubule polymerization | |

| 2-APB | Calcium signaling studies [6] | Cell-permeable inhibitor of IP3 receptors | |

| Regulatory Protein Markers | EB1-GFP | GTP-cap visualization and +TIP dynamics [25] | Binds growing microtubule ends, marker for GTP-tubulin |

| Anti-class III β-tubulin | Neuronal identification and differentiation [24] | Specific identifier for neurons in nervous tissue | |

| Signaling Inhibitors/Activators | BAPTA-AM | Calcium chelation experiments [6] | Cell-permeable calcium chelator |

| H 89 2HCl | PKA pathway inhibition [6] | Potent, selective inhibitor of PKA | |

| PMA (Phorbol ester) | PKC pathway activation [6] | PKC activator |

This toolkit represents essential reagents for investigating various aspects of microtubule dynamics, from basic polymerization assays to complex signaling pathway analysis. The selection of appropriate reagents depends on the specific research focus, whether on fundamental tubulin biochemistry, cellular microtubule organization, or in vivo dynamics in animal models.

Comprehensive Guide to Microtubule Orientation Quantification Techniques

Microtubules are dynamic cytoskeletal filaments crucial for intracellular organization, transport, and cell division in eukaryotes. Their structurally polar nature, with distinct plus and minus ends, underlies their fundamental functions. The plus ends of microtubules are particularly dynamic and serve as organizing centers within the cell, recruiting a specialized network of proteins known as microtubule plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs) [29]. Among these +TIPs, the End-Binding (EB) protein family stands out as central regulators that autonomously track growing microtubule ends and recruit additional binding partners [30] [29]. EB proteins, including EB1, EB2, and EB3, form homo- or heterodimers and serve as core scaffolding components that orchestrate the assembly of complex protein machinery at microtubule plus ends [29]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of fluorescent tagging approaches for EB-proteins as plus-end markers, with particular relevance to research investigating microtubule orientation quantification under varying environmental conditions, including light-dark cycles.

EB Protein Structure and Molecular Mechanisms

Structural Domains and Their Functions

EB proteins share a conserved structural organization featuring two critical domains: the N-terminal calponin homology (CH) domain that mediates microtubule binding, and the C-terminal EB homology domain (EBC) that facilitates dimerization and serves as the main docking site for other +TIPs [29]. Most +TIPs interact with the EBC domain through a conserved SxIP motif that binds to the hydrophobic cavity on the dimerized EBC domain [29]. This modular architecture enables EB proteins to simultaneously interact with microtubules while recruiting diverse binding partners to form the complex +TIP network.

Mechanism of Plus-End Tracking

EB proteins recognize specific structural features at growing microtubule ends, including GTP hydrolysis intermediates and unique tubulin interfaces unavailable on the mature microtubule lattice [31]. They bind to the outer microtubule surface in the grooves between adjacent protofilaments, close to the exchangeable GTP binding site [30]. As microtubules grow, EB molecules accumulate in characteristic comet-like distributions that gradually dissociate as the microtubule lattice matures and undergoes GTP hydrolysis [30]. This dynamic binding behavior allows EB proteins to precisely mark growing microtubule ends while excluding shrinking or paused microtubules.

Figure 1: EB Protein Mechanism at Microtubule Plus-Ends. EB proteins preferentially bind to GTP-tubulin-rich regions at growing microtubule ends, forming characteristic comet-like accumulations that dissociate as tubulin undergoes GTP hydrolysis and lattice maturation.

Comparative Analysis of Fluorescent Tagging Methodologies

Conventional Fluorescent Protein Tagging

Standard fluorescent tagging approaches fuse EB proteins with conventional fluorescent proteins such as enhanced GFP (eGFP). This method has been successfully employed to study EB1 dynamics in diverse experimental systems, including Drosophila sensory neurons where EB1-eGFP enabled quantification of cytoplasmic concentration and binding parameters [32]. Conventional tagging provides sufficient brightness for many live-cell imaging applications and allows straightforward quantification of molecular numbers and concentrations when properly calibrated [32]. However, the diffraction-limited resolution of conventional microscopy (approximately 200-300 nm) restricts the ability to resolve fine structural details at microtubule ends, which exhibit nanoscale features below this limit.

Advanced Superresolution Tagging Approaches

To overcome the resolution limitations of conventional microscopy, researchers have developed specialized tagging methods that enable superresolution imaging of EB proteins. The photoactivatable complementary fluorescent (PACF) protein system represents a significant advancement, allowing nanometer-scale localization of EB1 dimers in live cells [29]. This approach splits photoactivatable fluorescent proteins into complementary fragments that only become fluorescent when brought together by interacting proteins, significantly reducing background fluorescence while enabling precise single-molecule localization [29]. The PACF approach achieved a remarkable localization precision of 23 nm in fixed cells and 33 nm in live cells, revealing previously uncharacterized structural features of EB1 at microtubule ends [29].

Single-Molecule Calibration Techniques

Accurate quantification of EB protein numbers requires careful calibration of single-fluorophore intensity. The single-step bleaching kinetics method provides a robust approach for this calibration, even in challenging environments like tissues [32]. This technique exploits the quantized nature of photobleaching, where individual fluorophores disappear in discrete steps, allowing researchers to determine the intensity contribution of single molecules. Using this approach with spinning-disk confocal (SDC) microscopy, researchers established that single Alexa Fluor 488 molecules exhibited intensities of approximately 47 ADU per 100 ms exposure time, enabling absolute quantification of EB1-eGFP molecules in cellular environments [32].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fluorescent Tagging Methods for EB Proteins

| Method | Resolution | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional FP Tagging (eGFP, mCherry) | ~200-300 nm (diffraction-limited) | Broad compatibility; suitable for live-cell imaging; established protocols | Limited resolution for nanoscale details; photobleaching | Quantifying cytoplasmic EB1 concentration [32]; monitoring microtubule dynamics in tissues |

| PACF Superresolution | 23-33 nm localization precision | Nanoscale resolution in live cells; reduced background; precise dimer localization | Complex implementation; requires specialized analysis | Revealing EB1 dimer distribution patterns; structural plasticity in migrating cells [29] |

| Single-Molecule Bleaching Calibration | Single-molecule sensitivity | Absolute quantification of molecule numbers; works in tissues | Requires low fluorophore density; specialized analysis | Counting EB1-eGFP copies in comets; estimating binding parameters [32] |

| TIRF Microscopy | ~100 nm axial resolution | High signal-to-noise; single-molecule sensitivity; precise end tracking | Limited to surface-proximal structures | Analyzing EB1 density distributions; conformational transitions [30] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of EB Tagging Approaches

| Parameter | Conventional SDC | TIRF Microscopy | PACF Superresolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Fluorophore Intensity | 47 ± 3 ADU/100ms [32] | 600 ± 160 ADU/100ms [32] | Not quantitatively reported |

| Bleaching Time Constant | 24 ± 3 seconds [32] | 5.3 ± 1.1 seconds [32] | Comparable to PAGFP [29] |

| Localization Precision | Diffraction-limited | Diffraction-limited | 23 nm (fixed), 33 nm (live) [29] |

| End Tracking Precision | ~135 nm PSF [32] | ~135 nm PSF [32] | 10-23 nm [29] |

| Typical Concentration | 1-200 nM [32] [31] | 1-200 nM [32] [31] | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Single-Molecule Calibration via Stepwise Photobleaching

The quantification of absolute EB protein numbers requires careful calibration of single-fluorophore intensity using stepwise photobleaching:

- Sample Preparation: Immobilize microtubules lightly labeled with fluorescent tags (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488) on coverslips using anti-tubulin antibodies [32].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire time-lapse images using appropriate microscopy (SDC, TIRF, or epifluorescence) with consistent exposure settings (typically 100 ms exposure time) [32].

- Single Fluorophore Identification: Identify fluorescent puncta that display single-step photobleaching events in their intensity traces, confirming single-molecule status [32].

- Intensity Calibration: Measure the step sizes in fluorescence intensity when individual fluorophores bleach and compile these into a histogram to determine the average single-fluorophore intensity [32].

- Bleaching Kinetics Analysis: Fit the histogram of bleaching times to an exponential decay to determine the bleaching rate constant under specific illumination conditions [32].

This calibration enables the conversion of fluorescence intensity measurements into absolute numbers of EB proteins in cellular structures, such as the comets at growing microtubule ends.

PACF Superresolution Imaging Protocol

The photoactivatable complementary fluorescent (PACF) method enables superresolution imaging of EB1 dimers in live cells:

- Construct Design: Fuse EB1 to complementary fragments of photoactivatable GFP (nPACF and cPACF) to create EB1-PACF constructs that only fluoresce upon dimerization and photoactivation [29].

- Cell Transfection: Transiently transfect cultured cells (e.g., MCF7 cells) with EB1-PACF constructs using standard transfection methods [29].

- Photoactivation and Imaging: For fixed cells, acquire approximately 15,000 frames with 50 ms exposure per frame in TIRF mode after photoactivation with a 405 nm laser [29]. For live cells, reduce frames to 100 with 15 ms exposure to enable dynamic imaging [29].

- Single-Molecule Localization: Detect and precisely localize individual activated EB1-PACF molecules in each frame, achieving approximately 23 nm precision in fixed cells and 33 nm in live cells [29].

- Image Reconstruction: Compile all localized molecules into a superresolution image representing the nanoscale distribution of EB1 dimers [29].

This protocol revealed distinct EB1 distribution patterns between leading edges and cell bodies in migrating cells, with complex curving sheet-like structures at microtubule plus ends [29].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for EB Protein Fluorescent Tagging Studies. The comprehensive methodology encompasses construct design, cellular expression, sample preparation, advanced imaging, and quantitative analysis, supporting multiple specialized applications including single-molecule calibration, superresolution imaging, and dynamics analysis.

Applications in Microtubule Orientation Research

Investigating Microtubule End Maturation

EB fluorescent tagging has revealed fundamental insights into the conformational transitions that occur during microtubule end maturation. Using subpixel-precision analysis of EB1 density distributions, researchers discovered that growing microtubule ends undergo at least two distinct maturation steps with growth-velocity-independent kinetics [30]. EB1 binds after the first and before the second conformational transition, positioning it several tens of nanometers behind XMAP215, which binds to the extreme microtubule end [30]. This precise mapping of protein distributions at microtubule ends was enabled by quantitative fluorescence analysis of EB1 comets, revealing that EB1 accelerates microtubule maturation by promoting lateral protofilament interactions and potentially accelerating GTP hydrolysis [30].

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation at Microtubule Ends

Recent research utilizing EB fluorescent tags has demonstrated that +TIP networks can undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) at microtubule ends. Studies of the fission yeast EB homolog Mal3, kinesin Tea2, and cargo protein Tip1 revealed that these proteins form multivalent networks that can condense into liquid-phase droplets both in solution and at microtubule ends under crowding conditions [31]. Even in the absence of crowding agents, cryo-electron tomography showed that motor-dependent comets consist of disordered networks where multivalent interactions facilitate non-stoichiometric accumulation of cargo proteins [31]. Interestingly, different EB family members exhibit distinct LLPS properties, with EB3 having significantly higher phase separation propensity than EB1 despite 67% sequence identity, leading to differences in their capacity to recruit tubulin and nucleate polymerization [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EB Protein Tracking Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EB Protein Constructs | EB1-eGFP, EB3-mCherry, EB1-PACF | Core tracking markers; fusion partners for visualization | Dimerization required for tracking capability [29]; plant EB1b affects root directional growth [34] |

| Microtubule Labels | Alexa Fluor-labeled tubulin, Cy5-tubulin | Visualizing microtubule architecture and dynamics | Enable correlation of EB localization with microtubule ends [30] |

| Specialized Dyes | Alexa Fluor 488, Tetraspeck beads | Calibration standards and fiduciary markers | Single Alexa Fluor 488 intensity: 47 ADU/100ms (SDC) to 600 ADU/100ms (TIRF) [32] |

| Crowding Agents | PEG-6k, PEG-35k | Inducing phase separation; mimicking cellular environment | Promote formation of liquid-phase droplets at microtubule ends [31] |

| Microscopy Systems | Spinning-disk confocal (SDC), TIRF, PALM | Imaging at appropriate resolution and speed | SDC suitable for tissue imaging [32]; TIRF for single-molecule surface studies [30] |

The selection of appropriate fluorescent tagging approaches for EB proteins depends critically on research objectives and experimental constraints. For studies requiring absolute quantification of protein numbers in complex environments like tissues, single-molecule calibration via photobleaching kinetics provides unparalleled accuracy [32]. When investigating nanoscale architecture and structural plasticity of microtubule ends, PACF superresolution methods offer unprecedented spatial resolution in live cells [29]. Conventional fluorescent tagging remains valuable for high-temporal resolution tracking of microtubule dynamics and protein interactions in living systems. The growing recognition that EB proteins participate in biomolecular condensates through liquid-liquid phase separation [33] [31] opens new avenues for research, particularly in understanding how microtubule organization responds to environmental cues and cellular signaling events. As research progresses toward understanding microtubule dynamics under varying conditions, including light-dark cycles, the strategic combination of these complementary tagging approaches will continue to reveal fundamental mechanisms governing microtubule organization and function in diverse biological contexts.

Kymograph analysis is a fundamental methodology in live-cell imaging that converts spatial information over time into a visual representation, enabling researchers to quantify dynamic cellular processes with high temporal resolution. This technique is particularly valuable for studying the movement and kinetics of subcellular structures, such as microtubules and their associated proteins, under varying experimental conditions. Within the context of microtubule orientation quantification in light versus dark conditions, kymograph analysis provides the precise temporal and spatial resolution needed to capture rapid, transient events that characterize cytoskeletal responses to environmental stimuli [35] [36].

The fundamental principle behind kymograph generation involves disabling one spatial axis during image acquisition to convert it into a temporal axis. This transformation creates a two-dimensional plot where one dimension represents spatial position and the other represents time, effectively allowing researchers to visualize and quantify movement dynamics, velocities, and directional changes of cellular structures. Recent advances have pushed the temporal resolution of this methodology to approximately 30 milliseconds, enabling the detection of extremely brief and intermittent biological events that were previously undetectable with conventional imaging approaches [36].

For research investigating how light conditions influence microtubule organization, kymograph analysis offers unique advantages. It allows direct observation of microtubule polymerization dynamics, motor protein movements, and reorganization events in response to photoreceptor activation. This is particularly relevant for understanding phenomena such as phototropism, where directional growth toward light sources involves rapid cytoskeletal rearrangements. By applying kymograph analysis to live-cell imaging data collected under controlled light and dark conditions, researchers can extract quantitative parameters that reveal how environmental signals are transduced into structural changes within the cell [4] [37].

Comparative Analysis of Kymograph Methodologies

Quantitative Comparison of Kymograph Applications

Table 1: Comparison of kymograph methodologies across different experimental systems

| Experimental System | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters | Primary Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurofilament Transport Analysis [36] | 30 ms | ~200 nm (diffraction-limited) | Velocity, run length, pause frequency, directionality | Exceptional temporal resolution captures transient reversals and motor coordination |

| AFM-based Membrane Protein Dynamics [35] | 100 ms | ~1 Å vertical, ~10 Å lateral | Conformational state transitions, height/volume changes, lateral drift | Molecular-scale resolution under physiological conditions |

| Microtubule Plus-End Tracking [37] | 1-5 s | Diffraction-limited | Polymerization rate, catastrophe frequency, rescue events, tip complex occupancy | Correlates molecular function with cellular microtubule dynamics |

| Atomic Force Microscopy Viscoelastic Mapping [38] | Varies with method | Nanoscale | Storage modulus (ES), loss modulus (EL), loss angle (θ) | Quantifies mechanical properties alongside structural dynamics |

Performance Characteristics Across Imaging Platforms

Table 2: Technical performance across kymograph and end-tracking methodologies

| Methodology | Maximum Sustained Velocity Measurement | Processivity Tracking Duration | Multi-Parameter Extraction | Computational Processing Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Epifluorescence Kymography [36] | Up to 7.8 μm/s (retrograde) | 5-7.5 minutes continuous | Velocity, directionality, reversals, pause dynamics | Moderate (edge detection algorithms) |

| AFM Kymography [35] | Limited by scan rate | ~25 seconds per kymograph | Conformational states, mechanical properties, drift quantification | High (requires drift correction simulations) |

| TIRF Microscopy Plus-End Tracking [37] | Limited by frame rate | Minutes to hours | Polymerase activity, dwell time, tubulin recruitment | High (single-particle tracking algorithms) |

| Z-Transform Viscoelastic Mapping [38] | N/A (static properties) | N/A | Viscoelastic properties at multiple time scales | Very high (37,386x faster than traditional methods) |

Experimental Protocols for Kymograph Analysis

High-Temporal Resolution Kymograph Protocol for Axonal Transport

This protocol, adapted from studies of neurofilament transport, achieves 30 ms temporal resolution essential for capturing rapid, intermittent movements:

Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Transfect rat cortical neurons with fluorescent protein-tagged constructs (e.g., pEGFP-NFM for neurofilaments) using nucleofection protocols [36].