Optimizing Actin-Microtubule Co-Entangled Networks: A Guide to Tunable Mechanics and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the engineering and optimization of composite cytoskeletal networks.

Optimizing Actin-Microtubule Co-Entangled Networks: A Guide to Tunable Mechanics and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the engineering and optimization of composite cytoskeletal networks. It explores the emergent mechanical properties of co-entangled actin-microtubule composites, detailing protocols for their reconstitution and active manipulation with molecular motors. The content covers foundational principles of tunable stiffness and power-law stress relaxation, methodologies for creating biomimetic active materials, strategies for troubleshooting network heterogeneities, and comparative analyses of composite performance. By synthesizing recent advances in this field, this guide aims to bridge fundamental biophysical insights with practical applications in cellular engineering and therapeutic development.

Emergent Properties in Actin-Microtubule Composites: Stiffness, Relaxation, and Network Mechanics

FAQs: Actin-Microtubule Composite Fundamentals

Q1: What are the key structural and mechanical differences between actin filaments and microtubules? Actin filaments and microtubules possess distinct properties that make their interplay in composites mechanically complex. Actin filaments are semi-flexible polymers approximately 7 nm wide with a persistence length of about 10 µm [1] [2]. Microtubules are much more rigid, with a width of 25 nm and a persistence length of approximately 1 mm [1] [2]. This difference in flexibility is a primary reason for the emergent mechanical properties observed in their composites.

Q2: Do actin and microtubule filaments interact directly in vitro? No, current evidence indicates that actin filaments and microtubules do not directly interact on their own [3]. Instead, their crosstalk is mediated by additional proteins or complexes that contain specific binding sites for both polymers [3]. These mediators include motor proteins, fascin, tau, and spectraplakins, which can bundle individual polymers and directly link actin to microtubules [3].

Q3: Why is the molar fraction of each filament type critical in composite design? The molar fraction of tubulin (ϕT) significantly influences the mechanical behavior of composites. Research shows that a large fraction of microtubules (>0.7) is needed to substantially increase the measured resistive force in composites [1]. Furthermore, composites undergo a sharp transition from strain softening to stiffening when ϕT exceeds 0.5 [1]. Equimolar composites (ϕT = 0.5) exhibit unique properties, including maximum filament mobility and fastest reptation dynamics [1].

Q4: How does actin prevent mechanical heterogeneities in composites? Actin minimizes mechanical heterogeneities by reducing the mesh size of the composites and providing structural support that prevents microtubules from buckling under compressive forces [1]. The smaller mesh size created by the actin network creates a more uniform mechanical environment throughout the composite.

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Q5: How can I achieve properly integrated, isotropic co-entangled composites? Avoid methods that mix pre-polymerized filaments, as this can cause flow alignment, microtubule shearing, and actin bundling [1]. Instead, use optimized co-polymerization: incubate actin monomers and tubulin dimers together in a hybrid buffer (100 mM PIPES pH 6.8, 2 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 5 μM Taxol) at 37°C for 1 hour [1]. This ensures simultaneous polymerization of both networks, resulting in well-mixed, isotropic composites without phase separation or nematic ordering.

Q6: My composites exhibit inconsistent mechanical responses. What might be wrong? Inconsistent responses often stem from improper crosslinking strategies. Research reveals that varying crosslinking motifs create fundamentally different mechanical behaviors [2]. For example, crosslinking microtubules to each other or to actin (Co-linked) produces a more elastic response, whereas crosslinking only actin leads to softer, more viscous behavior [2]. Ensure your crosslinking strategy matches your desired mechanical outcome and that crosslinker concentrations are precisely controlled.

Q7: How can I control contraction and restructuring in active composites? For active composites incorporating myosin, achieving controlled dynamics requires a critical fraction of microtubules [4] [5]. While percolated actomyosin networks are essential for contraction, only composites with comparable actin and microtubule densities can simultaneously resist mechanical stresses while supporting substantial restructuring [4] [5]. Tune the actin:microtubule ratio and motor density to balance these competing requirements.

Table 1: Mechanical Transitions in Actin-Microtubule Composites (11.3 μM total protein)

| Molar Fraction of Tubulin (ϕT) | Primary Mechanical Response | Force Relaxation Profile | Filament Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|

| ϕT < 0.5 | Strain softening dominates | Power-law decay | Increases with ϕT |

| ϕT = 0.5 (Equimolar) | Transition point | Fastest reptation dynamics | Maximum mobility |

| ϕT > 0.5 | Strain stiffening dominates | Slower reptation | Decreases with ϕT |

| ϕT > 0.7 | Substantially increased force | Poroelastic relaxation | Limited, heterogeneous |

Table 2: Mechanical Classes by Crosslinking Motif (Equimolar Composites)

| Crosslinking Motif | Mechanical Class | Force Response | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (Entangled only) | Class 1 (Viscous) | Softening, yielding | Complete force relaxation |

| Actin-Actin only | Class 1 (Viscous) | Softening, yielding | Similar to uncrosslinked |

| Both crosslinked | Class 1 (Viscous) | Softening, yielding | Less effective elasticity |

| Microtubule-MT only | Class 2 (Elastic) | Linear, non-yielding | Sustained force, memory |

| Actin-MT Co-linked | Class 2 (Elastic) | Linear, non-yielding | Maximum elasticity |

| Both (2x crosslinker) | Class 2 (Elastic) | Linear, non-yielding | Enhanced elasticity |

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Creating Co-Entangled Actin-Microtubule Composites

Key Materials:

- Rabbit skeletal actin & porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton, Inc.)

- Alexa-488-labeled actin & rhodamine-labeled tubulin (for visualization)

- Polymerization buffer: 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.8), 2 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 5 μM Taxol

- Oxygen scavenging system: 4.5 mg/mL glucose, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol, 4.3 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.7 mg/mL catalase

Procedure:

- Prepare monomer solution with desired molar ratio of unlabeled actin and tubulin to reach 11.3 μM total protein concentration in polymerization buffer [1].

- Add tracer filaments: 0.13 μM pre-assembled Alexa-488-labeled actin (1:1 labeled:unlabeled) and 0.19 μM pre-assembled rhodamine-labeled microtubules (1:5 labeling ratio) [1].

- Incorporate oxygen scavenging agents to prevent photobleaching during future imaging [1].

- Add sparse 4.5 μm diameter microspheres for microrheology measurements [1].

- Pipette protein-bead mixture into a sample chamber (glass slide and coverslip separated by ~100 μm with double-sided tape) and seal with epoxy [1].

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to allow co-polymerization into stable, co-entangled composites [1].

Validation:

- Confirm filament lengths: actin ~8.7 ± 2.8 μm; microtubules ~18.8 ± 9.7 μm [1]

- Verify isotropic, well-mixed structure with no bundling, aggregation, or phase separation [1]

- Check that single-component controls exhibit expected mechanical properties [1]

Protocol: Microrheology Measurements

Equipment:

- Optical tweezers system

- Fluorescence microscopy capabilities

- Temperature control (37°C)

Procedure:

- Identify embedded microspheres within composite samples [1].

- Using optical tweezers, displace selected microsphere 30 μm at speed >> system relaxation rates [1].

- Simultaneously measure force exerted on bead by filaments and subsequent force relaxation [1].

- Repeat across multiple locations and samples to account for heterogeneity [1].

- For active composites, combine with differential dynamic microscopy and spatial image autocorrelation to quantify contraction dynamics [4].

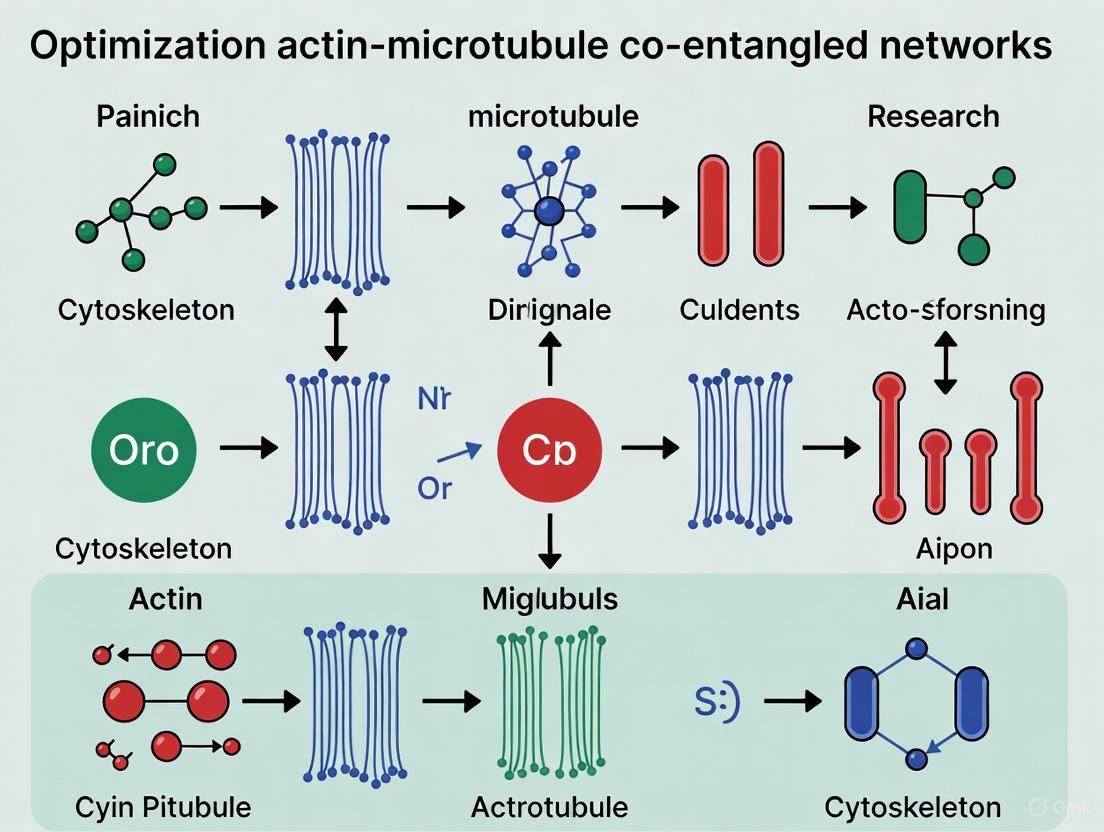

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Actin-Microtubule Composite Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Source / Product |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit Skeletal Actin | Primary filament component for flexible network | Cytoskeleton, Inc. (AKL99) |

| Porcine Brain Tubulin | Primary filament component for rigid network | Cytoskeleton, Inc. (T240) |

| Taxol (Paclitaxel) | Stabilizes microtubules against depolymerization | Various suppliers |

| Biotin-NeutrAvidin Complex | Modular crosslinking system for varying motifs | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Alexa-488-labeled Actin | Fluorescent tracer for actin visualization | Thermo Fisher Scientific (A12373) |

| Rhodamine-labeled Tubulin | Fluorescent tracer for microtubule visualization | Cytoskeleton, Inc. (TL590M) |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Prevents photobleaching during extended imaging | Glucose oxidase/catalase system |

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Handles for optical tweezers microrheology | Polysciences (4.5 μm diameter) |

Tunable Stiffness and Power-Law Stress Relaxation in Co-Entangled Networks

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Protocol: Forming Actin-Microtubule Composites

This protocol details the creation of isotropic, co-entangled actin-microtubule composites for mesoscale mechanical characterization [1].

Key Reagents:

- Rabbit skeletal actin and porcine brain tubulin.

- Rhodamine-labeled tubulin and Alexa-488-labeled actin (for fluorescence visualization).

- PIPES buffer (100 mM, pH 6.8).

- MgCl₂ (2 mM), EGTA (2 mM).

- ATP (2 mM) and GTP (1 mM) for actin and tubulin polymerization, respectively.

- Taxol (5 µM) to stabilize polymerized microtubules.

- Oxygen scavenging system (glucose, glucose oxidase, catalase, β-mercaptoethanol) to prevent photobleaching.

Polymerization Procedure:

- Preparation: Suspend unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers at the desired molar ratio in the aqueous buffer containing all nucleotides and salts. The total protein concentration should be 11.3 µM. Include trace amounts ( ~1% of filaments) of pre-assembled, fluorescently labeled actin and microtubules for imaging.

- Incubation: Add the protein-buffer mixture to a sample chamber and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour. This step co-polymerizes both proteins in situ, resulting in a well-integrated, stable composite network.

- Validation: Use fluorescence microscopy to confirm the formation of an isotropic, well-mixed network without bundling, aggregation, or phase separation. Filament lengths should be approximately 8.7 ± 2.8 µm for actin and 18.8 ± 9.7 µm for microtubules, independent of composition.

Protocol: Nonlinear Mesoscale Mechanics via Optical Tweezers

This method characterizes the nonlinear force response and relaxation of the composites [1].

- Key Equipment: Optical tweezers system, fluorescence microscope, sample chamber.

- Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Incorporate a sparse number of 4.5 µm diameter microspheres into the composite solution before polymerization.

- Perturbation: Use optical tweezers to displace a single embedded microsphere a distance of 30 µm. This distance is greater than the filament lengths, and the speed is much faster than the network's intrinsic relaxation rates, perturbing the system far from equilibrium.

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously measure the force exerted on the bead by the filament network and the subsequent force relaxation over time.

- Analysis: Analyze the force-distance curves and the time-dependent force relaxation to extract parameters like peak force and relaxation exponents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for actin-microtubule composite experiments.

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Actin (unlabeled & fluorescent) | Primary semiflexible filament network component | Persistence length ~10 µm; Polymerizes into ~7 nm filaments [1] |

| Tubulin (unlabeled & fluorescent) | Primary rigid filament network component | Persistence length ~1 mm; Polymerizes into 25 nm hollow microtubules [1] |

| PIPES Buffer | Maintains physiological pH during polymerization | 100 mM concentration, pH 6.8 [1] |

| ATP & GTP | Provides energy for polymerization | ATP for actin; GTP for tubulin [1] |

| Taxol | Stabilizes microtubules | Prevents depolymerization; used at 5 µM concentration [1] |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Reduces photobleaching during fluorescence imaging | Includes glucose, glucose oxidase, and catalase [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Composite Formation and Structure

Q1: Our composites show signs of bundling or phase separation instead of a homogeneous network. What could be wrong?

- A1: This is often related to suboptimal polymerization conditions. Ensure you are using the recommended buffer (PIPES at pH 6.8) and nucleotide concentrations. Critically, the method of in situ co-polymerization (mixing monomers and polymerizing together) is essential to prevent flow alignment and shearing that occurs when adding pre-polymerized filaments. Verify that your incubation time and temperature (1 hour at 37°C) are precise [1].

Q2: How do I control the mesh size of the composite network?

- A2: The mesh size (ξ) is concentration-dependent. For single-component networks, the relationships are ξA = 0.3/√cA for actin and ξM = 0.89/√cT for microtubules (concentrations in mg/mL). In a composite, the mesh size becomes a function of the relative molar fraction of tubulin (ϕT). A higher actin fraction generally reduces the mesh size and minimizes structural heterogeneities [1].

Mechanical Properties and Data Interpretation

Q3: We are not observing the expected strain-stiffening behavior. What factor are we likely missing?

- A3: The transition from strain-softening to strain-stiffening is highly dependent on composition. Your composite requires a sufficient fraction of microtubules. The search results indicate a sharp transition when the fraction of microtubules (ϕT) exceeds 0.5. Ensure you are using a tubulin molar fraction above this threshold to observe strain-stiffening [1].

Q4: Our force relaxation data does not show a clear power-law decay. What could be affecting the measurement?

- A4: First, confirm that your perturbation is sufficiently large and fast. The bead should be displaced a distance greater than the filament length at a speed faster than the network's relaxation. Second, analyze the long-time regime (t > 0.06 s in the referenced study). The initial short-time relaxation is dominated by poroelasticity and bending. The characteristic power-law decay, indicative of reptation, becomes evident at longer timescales [1]. The scaling exponent for this decay exhibits a nonmonotonic dependence on ϕT, peaking at equimolar (ϕT = 0.5) composites [1].

Q5: What is the origin of power-law stress relaxation in entangled polymers without ends?

- A5: For entangled rings (polymers without ends), stress relaxes via a self-similar process of hierarchical loop rearrangements, not by reptation. This dynamics yields a power-law stress relaxation modulus, G(t) ~ t⁻⁴⁄₅, rather than the plateau and exponential decay seen in linear polymers. This is a fundamental difference in the relaxation mechanism of topologically constrained rings [6].

Table 2: Composition-dependent mechanical properties of actin-microtubule composites.

| Molar Fraction of Tubulin (ϕT) | Mechanical Response | Strain Behavior | Long-time Relaxation Exponent | Filament Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕT < 0.5 | Lower measured force | Strain softening | Lower scaling exponent | Reduced mobility |

| ϕT = 0.5 | Intermediate force | Transition point | Maximum scaling exponent | Highest mobility for both filaments |

| ϕT > 0.7 | Substantially increased force, large heterogeneities | Strain stiffening | Lower scaling exponent | Reduced mobility |

Experimental Workflow and Relaxation Mechanisms

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for creating and characterizing actin-microtubule composites.

Figure 2: Mechanisms of stress relaxation in entangled composites after a nonlinear perturbation.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my composite network exhibit high heterogeneity in force response, and how can I minimize it?

- Problem: Large variations in measured force are observed when performing microrheology.

- Solution: A high proportion of microtubules (>70%) is required to substantially increase the measured force, but this is accompanied by significant heterogeneity. To minimize these heterogeneities, increase the actin fraction in your composite. Actin reduces the network mesh size and provides lateral support to microtubules, preventing them from buckling and creating a more uniform mechanical response [7] [1].

FAQ 2: I cannot replicate the sharp strain-stiffening transition at a tubulin fraction (ϕT) of 0.5. What could be wrong?

- Problem: The expected transition from strain softening to strain stiffening is not observed.

- Solution: Ensure your composites are truly co-entangled and isotropic. Pre-polymerizing filaments separately and then mixing can induce flow alignment, shearing, and bundling. Use the co-polymerization protocol: incubate actin monomers and tubulin dimers together in a single optimized buffer at 37°C for 1 hour. This method promotes a well-integrated, random network essential for the emergent stiffening transition at ϕT = 0.5 [1].

FAQ 3: The filament mobility in my composite does not match published data. How is mobility optimized?

- Problem: Filament reptation and network rearrangements are slower or faster than expected.

- Solution: Filament mobility exhibits a nonmonotonic dependence on composition. The highest mobility and fastest reptation scaling exponents occur at an equimolar ratio (ϕT = 0.5). If your mobility is low, check your composite ratio. Networks with a ϕT of 0.5 have an optimized balance where the mesh size and filament rigidity interact to maximize filament disengagement from entanglement constraints [7] [1].

FAQ 4: How can I create an active, dynamic composite that mimics the cytoskeleton more closely?

- Problem: My network is mechanically sound but static, lacking adaptive plasticity.

- Solution: Incorporate dynamic assembly and molecular motors. Use microtubule seeds with free tubulin and GTP for microtubule growth, and combine with actin monomers and ATP. To drive self-organization, attach kinesin motors to surfaces for microtubule motility or incorporate myosin II minifilaments to generate contractile forces in the presence of ATP. This creates a life-like system capable of structural memory and reorganization [8] [9].

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Actin-Microtubule Composites vs. Composition

| Tubulin Fraction (ϕT) | Strain Response | Force Heterogeneity | Long-time Relaxation Exponent | Filament Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕT < 0.5 | Strain Softening | Low | Lower | Lower |

| ϕT = 0.5 | Transition to Strain Stiffening | Moderate | Maximum (Peak) | Maximum (Peak) |

| ϕT > 0.7 | Strain Stiffening | High (Substantial) | Lower | Lower |

Data Notes: The total protein concentration for the composites summarized above was held constant at 11.3 μM [1]. The force heterogeneity is minimized by a higher actin fraction, which reduces mesh size and supports microtubules against buckling [7].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Experimentation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Experiment | Key Details / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Dimers | Polymerizes to form rigid microtubules. | Use with GTP for polymerization. Persistence length ~1 mm [1]. |

| Actin Monomers | Polymerizes to form semiflexible actin filaments (F-actin). | Use with ATP for polymerization. Persistence length ~10 μm [1]. |

| Taxol | Stabilizes microtubules against depolymerization. | Typically used at 5 μM in composite protocols [1]. |

| Optical Tweezers | To perturb the network and measure nonlinear mesoscale mechanics. | Used to displace embedded microspheres and measure force/relaxation [7] [1]. |

| Myosin II Minifilaments | Drives contractile activity in composite networks. | A 1:12 molar ratio of myosin:actin is a common starting point [9]. |

| Kinesin Motors | Drives microtubule motility and network reorganization. | Often attached to a passivated glass surface in assays [8]. |

Standard Experimental Protocol: Co-Entangled Composite Formation & Microrheology

This protocol details the creation of well-mixed, isotropic actin-microtubule composites and the characterization of their mechanical properties via optical tweezers microrheology [1].

Part 1: Sample Chamber and Buffer Preparation

- Prepare Hybrid Buffer: Create an aqueous buffer containing 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.8), 2 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, and 1 mM GTP. This buffer supports the polymerization of both actin and tubulin.

- Prepare Sample Chamber: Construct a chamber from a glass slide and coverslip, separated by ~100 μm using double-sided tape, and seal with epoxy.

Part 2: Co-polymerization of Actin-Microtubule Composites

- Mix Proteins: Combine unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers in the hybrid buffer to the desired molar ratio (e.g., ϕT = 0.5 for equimolar). Maintain a final total protein concentration of 11.3 μM.

- Add Stabilizers and Tracers: Include 5 μM Taxol to stabilize microtubules. For visualization, add trace amounts ( ~1% of total protein) of pre-assembled, fluorescently labeled actin filaments and microtubules.

- Add Microspheres: Incorporate a sparse concentration of 4.5 μm diameter microspheres, coated with BSA to prevent non-specific binding.

- Polymerize: Pipette the mixture into the sample chamber and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour. This co-polymerization results in a stable, co-entangled 3D network.

Part 3: Nonlinear Mesoscale Mechanics Measurement

- Perturb Network: Use optical tweezers to displace an embedded microsphere a distance of 30 μm. This distance is greater than the filament lengths, and the speed should be faster than the network's intrinsic relaxation rate.

- Measure Force: Simultaneously measure the force the filament network exerts on the bead during displacement.

- Record Relaxation: Track the subsequent force relaxation over time after the displacement ceases.

- Analyze Data: The force relaxation profile will typically show a power-law decay after a short initial period. Analyze the scaling exponents for the long-time relaxation, which is indicative of filament reptation.

Visualizing the Mechanical Transition

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanical and dynamic transitions that occur at the critical tubulin fraction of ϕT = 0.5, based on experimental findings.

The Role of Mesh Size and Filament Rigidity in Mechanical Response

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my composite network exhibit high heterogeneity in force response? High heterogeneity is often observed when the microtubule fraction (φT) is large (>0.7). This occurs because microtubules, being stiff filaments, bear compressive loads unevenly. To minimize this heterogeneity, increase the actin fraction in your composite. Actin reduces the network mesh size and provides lateral support to microtubules, preventing them from buckling and creating a more uniform mechanical response [7] [1].

FAQ 2: How can I induce strain stiffening instead of softening in my composite? Ensure the fraction of microtubules (φT) in your composite exceeds 0.5. Composites undergo a sharp transition from strain softening to stiffening when φT > 0.5. This transition arises from faster poroelastic relaxation and the suppression of actin bending fluctuations by the stiffer microtubules [7] [1].

FAQ 3: My composite fluidizes instead of maintaining elasticity. What is the cause? This may be due to kinesin-driven de-mixing at high motor concentrations. Kinesin motors can cause microtubules to cluster into dense aggregates, disrupting the space-spanning network and leading to fluidization. To maintain elasticity, use intermediate kinesin concentrations or optimize the actin-to-microtubule ratio (e.g., 45:55 molar ratio) to support network connectivity during active restructuring [10].

FAQ 4: Why is filament mobility suboptimal in my composites? Filament mobility, crucial for stress relaxation, exhibits a nonmonotonic dependence on composition. The highest mobility for both actin and microtubules occurs in equimolar composites (φT = 0.5). If mobility is low, adjust your actin-to-tubulin ratio toward equimolar concentrations. This optimizes the interplay between mesh size and filament rigidity, allowing for faster reptation [7] [1].

FAQ 5: How do I prevent kinesin-driven de-mixing in active composites? Kinesin-driven de-mixing is concentration-dependent. While low concentrations may have minimal effect, high kinesin concentrations robustly drive the formation of microtubule-rich aggregates. To maintain a well-mixed, interpenetrating network, titrate the kinesin concentration to the lowest level that produces your desired activity, or use a composite formulation (e.g., 45:55 actin-to-tubulin) known to resist large-scale flow and rupture [10].

Table 1: Mechanical Transitions and Relaxation in Passive Composites

| Microtubule Fraction (φT) | Mechanical Response | Force Relaxation Scaling Exponent | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| φT < 0.5 | Strain softening | Lower values | Actin-dominated; larger bending fluctuations |

| φT = 0.5 | Transition point | Maximum value | Optimal filament mobility; fastest reptation |

| φT > 0.5 | Strain stiffening | Nonmonotonic dependence | Microtubule-dominated; suppressed actin bending |

| φT > 0.7 | High force, high heterogeneity | N/A | Requires actin to reduce heterogeneity and prevent buckling |

Table 2: Impact of Kinesin Motors on Active Composite Mechanics

| Kinesin Concentration | Network Structure | Mechanical Behavior | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Well-mixed, interpenetrating | Softer, more viscous dissipation | Studying baseline active mechanics |

| Intermediate | Onset of de-mixing; microtubule clusters | Emergent stiffness and resistance | Achieving enhanced elastic response |

| High | De-mixed; microtubule-rich aggregates in actin phase | Softer, potential fluidization | Investigating phase separation and aggregation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Forming Co-Entangled Passive Composites for Microrheology

This protocol creates isotropic, well-mixed actin-microtubule composites for nonlinear mesoscale mechanics characterization [1].

Reagents and Buffers:

- G-Buffer: 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM CaCl₂, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT.

- M-Buffer: 10 mM imidazole (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM ATP.

- TEAM Buffer: 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.8), 2 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 5 μM Taxol.

- Oxygen Scavenging System: 4.5 mg/mL glucose, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol, 4.3 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.7 mg/mL catalase.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Mix unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers in TEAM buffer to a final total protein concentration of 11.3 μM. Systematically vary the molar fraction of tubulin, φT, from 0 to 1.

- For fluorescence visualization, include tracer filaments: 0.13 μM of pre-assembled Alexa-488-labeled actin (1:1 labeled:unlabeled ratio) and 0.19 μM of pre-assembled rhodamine-labeled microtubules (1:5 labeling ratio). This ensures only ~1% of filaments are labeled, allowing single-filament resolution.

- Add a sparse concentration of 4.5 μm diameter microspheres (e.g., from Polysciences) for microrheology measurements. Coat beads with Alexa-488 BSA to prevent non-specific protein adhesion.

Co-Polymerization:

- Pipette the protein-bead mixture into a sample chamber constructed from a glass slide and coverslip separated by ~100 μm.

- Seal the chamber with epoxy to prevent evaporation.

- Incubate the sample for 1 hour at 37°C to allow simultaneous polymerization of actin and microtubules, forming a stable, co-entangled network.

Validation of Network Structure:

- Use fluorescence microscopy to confirm the network is isotropic and well-mixed, with no visible bundling, aggregation, or phase separation.

- Verify filament lengths are approximately 8.7 ± 2.8 μm for actin and 18.8 ± 9.7 μm for microtubules, independent of φT.

Protocol 2: Performing Optical Tweezers Microrheology

This protocol details how to perturb composites far from equilibrium to measure nonlinear force response and relaxation [7] [1].

Equipment:

- Optical tweezers system capable of high-force trapping and precise bead positioning.

- High-speed camera for tracking bead displacement and recording force data.

- Fluorescence microscope (confral recommended) for simultaneous structural imaging.

Procedure:

- Bead Selection and Positioning:

- Identify a well-isolated, embedded 4.5 μm microsphere within the 3D composite network away from chamber surfaces.

Nonlinear Perturbation:

- Using optical tweezers, displace the selected bead a distance of 30 μm. This distance is greater than the filament lengths, ensuring the network is perturbed far from equilibrium.

- Perform the displacement at a speed much faster than the intrinsic relaxation rates of the filaments (e.g., several μm/ms).

Simultaneous Force and Relaxation Measurement:

- During and after displacement, measure the force exerted on the bead by the filament network using laser deflection or momentum methods.

- After reaching the maximum displacement, hold the bead stationary and record the force relaxation over time (typically several seconds).

- Simultaneously acquire fluorescence images to correlate mechanical response with structural rearrangements.

Data Analysis:

- Force Response: Analyze the peak force and its heterogeneity across multiple beads and samples.

- Relaxation Dynamics: Fit the long-time force relaxation (t > 0.06 s) to a power-law decay (F ∝ t^−α). The scaling exponent (α) reveals information about filament reptation.

- Short-time Dynamics: Analyze the initial period (t < 0.06 s) for poroelastic and bending contributions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Protein | Polymerizes to form rigid microtubules; key structural component. | Porcine brain source is common; ensure high purity to prevent failed polymerization. |

| Actin Protein | Polymerizes to form semi-flexible F-actin; fills meshwork and supports microtubules. | Rabbit skeletal muscle source is standard; handle gently to prevent denaturation. |

| Taxol | Stabilizes polymerized microtubules against depolymerization. | Critical for long-term experiments; use at 5 μM in composites [1]. |

| Kinesin Motors | Generates internal forces and drives network restructuring in active composites. | Dimer clusters are often used; concentration titrates mechanical response [10]. |

| ATP & GTP | Provides energy for actin and microtubule polymerization, respectively. | Essential for polymerization buffer; include at 2 mM concentration [1]. |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Reduces photobleaching during fluorescence microscopy. | Include glucose, β-mercaptoethanol, glucose oxidase, and catalase [1]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Kinesin-Driven Restructuring and Mechanical Response

Diagram 2: Passive Composite Mechanics and Relaxation

Poroelastic Relaxation and Reptation in Long-Time Stress Decay

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High heterogeneity in force response | Microtubule fraction (ϕT) > 0.7 without sufficient actin support [1] [11] | Measure force response across multiple bead displacements; check composite composition via fluorescence [1] | Increase actin fraction to reduce mesh size (ξ) and provide lateral support against microtubule buckling [1] [11] |

| Insufficient network stiffness | Low microtubule fraction (ϕT < 0.5) [1] [11] | Confirm protein molar ratios during polymerization; verify tubulin polymerization success [1] | Increase tubulin fraction to at least ϕT = 0.5 to promote strain stiffening [1] [11] |

| Abnormal reptation dynamics (non-power-law decay) | Incorrect co-polymerization leading to phase separation [1] | Use fluorescence microscopy to check for filament aggregation or nematic structure [1] | Optimize buffer conditions (pH, nucleotides) and ensure simultaneous co-polymerization at 37°C for 1 hour [1] |

| Uncontrolled actin network density | Lack of spatiotemporal control over nucleation [12] | Quantify network density from fluorescence images [12] | Implement optogenetic systems (e.g., OptoVCA) for precise, light-controlled actin assembly on lipid membranes [12] |

Table 2: Optimizing Composite Mechanics for Drug Screening

| Research Goal | Ideal Composite Parameters | Key Readouts | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screen tubulin-targeting compounds [13] | High microtubule fraction (ϕT > 0.7) [1] [11] | Force response magnitude; relaxation exponent changes [1] [11] [13] | Maximizes microtubule contribution for detecting polymerization/depolymerization effects [13] |

| Study cytoskeletal crosstalk | Equimolar composition (ϕT = 0.5) [1] [11] | Filament mobility (FRAP); long-time relaxation exponent [1] [11] | Maximizes filament reptation and emergent cooperative mechanics [1] [11] |

| Model intracellular mechanics | Actin-rich with low microtubule fraction (ϕT ~ 0.3) [1] | Porosity; short-time poroelastic relaxation [1] | Creates dense mesh similar to cortical cytoplasm; actin dominates mechanics [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical microtubule fraction for the strain softening-to-stiffening transition, and why is it important?

A transition from strain softening to stiffening occurs when the microtubule fraction (ϕT) exceeds 0.5 [1] [11]. This is critical for drug screening applications because it signifies a fundamental shift in the composite's mechanical response to large deformations, moving from a softening actin-dominated regime to a stiffening microtubule-reinforced regime. This transition arises from faster poroelastic relaxation and suppressed actin bending fluctuations, making the network more resilient [1] [11].

Q2: How do poroelastic relaxation and reptation contribute to stress decay at different timescales?

The force relaxation profile in co-entangled composites is biphasic [1] [11]:

- Short-time relaxation (t < 0.06 s): Dominated by poroelastic processes and filament bending. This involves fluid flow through the composite pores and local bending of filaments [1] [11].

- Long-time relaxation (t > 0.06 s): Characterized by a power-law decay, which is a signature of reptation. In this process, filaments diffuse curvilinearly out of their tube-like constraints formed by the surrounding entangled network [1] [11].

Q3: Our composites show inconsistent mechanics. How can we ensure proper formation of a co-entangled network?

Inconsistent mechanics often stem from improper network formation. To ensure well-integrated, isotropic composites [1]:

- Co-polymerize in situ: Do not mix pre-polymerized filaments. Instead, combine actin monomers and tubulin dimers in a single buffer and incubate together at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Use optimized hybrid buffer: 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.8), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, and 5 μM Taxol.

- Verify structure: Use tracer filaments (e.g., ~1% fluorescently labeled) to confirm a randomly oriented, well-mixed network without bundling or phase separation via fluorescence microscopy.

Q4: How can we precisely control actin network density to study steric effects on drug penetration?

Traditional methods offer limited control. For precise spatiotemporal manipulation, implement an optogenetic system like OptoVCA [12]. This system uses a light-inducible dimer (iLID-SspB) to recruit the VCA domain of WAVE1 to a lipid membrane upon blue light illumination, triggering localized Arp2/3-mediated actin assembly. By tuning illumination power, duration, and pattern, you can flexibly manipulate the density, thickness, and shape of the actin network to systematically study how density creates steric barriers for large protein complexes or drug candidates [12].

Table 3: Quantitative Relaxation Parameters vs. Tubulin Fraction

| Tubulin Fraction (ϕT) | Short-Time Relaxation (<0.06s) Mechanism | Long-Time Relaxation Exponent | Filament Mobility | Key Mechanical Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 (Actin only) | Poroelastic & bending [1] [11] | Lower value [1] [11] | Baseline | Strain softening [1] [11] |

| 0.5 (Equimolar) | Faster poroelastic [1] [11] | Maximum value [1] [11] | Highest [1] [11] | Transition point [1] [11] |

| 1.0 (MT only) | Poroelastic [1] [11] | Lower value [1] [11] | Baseline | High force, high heterogeneity [1] [11] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Forming Co-Entangled Actin-Microtubule Composites

- Materials: Rabbit skeletal actin, porcine brain tubulin, rhodamine-tubulin, Alexa-488-actin, PIPES buffer, MgCl2, EGTA, ATP, GTP, Taxol [1].

- Procedure [1]:

- Mix unlabeled actin and tubulin to a final total protein concentration of 11.3 μM in the optimized buffer, including nucleotides and 5 μM Taxol.

- Include a sparse amount (~1% of total protein) of pre-assembled fluorescent tracer filaments for visualization.

- Add oxygen scavengers (glucose, β-mercaptoethanol, glucose oxidase, catalase) to prevent photobleaching.

- Incubate the mixture in a sealed sample chamber for 1 hour at 37°C to co-polymerize both networks simultaneously.

Protocol 2: Optical Tweezers Microrheology Measurement

- Materials: 4.5 μm diameter microspheres, coated with Alexa-488 BSA to prevent non-specific binding, optical tweezers system, fluorescence microscope [1].

- Procedure [1]:

- Embed coated microspheres sparsely within the polymerized composite.

- Use optical tweezers to displace a bead by 30 μm (a distance greater than filament lengths) at a speed much faster than the system's relaxation rate.

- Simultaneously measure the force exerted on the bead by the network and track the subsequent force relaxation over time.

- Correlate force measurements with network structure via simultaneous fluorescence microscopy.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Actin-Microtubule Composite Research

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin (unlabeled & fluorescent) [1] | Forms microtubule filaments; rigid network component | Use with GTP for polymerization; stabilize with Taxol [1] |

| Actin (unlabeled & fluorescent) [1] | Forms F-actin; semiflexible network component | Use with ATP for polymerization [1] |

| Taxol [1] | Stabilizes microtubules against depolymerization | Critical for maintaining composite integrity during long experiments [1] |

| OptoVCA System (iLID & SspB-VCA) [12] | Enables light-controlled actin assembly | Essential for spatially and temporally precise network density studies [12] |

| BSA-coated Microspheres [1] | Inert probes for microrheology | Coating prevents sticking to filaments [1] |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Actin-microtubule composites are co-entangled networks formed by polymerizing actin filaments and microtubules together, creating a biomechanical environment that mimics key aspects of the cellular cytoskeleton. These composite systems exhibit emergent mechanical properties that are not simply the sum of their individual components, making them valuable model systems for studying intracellular mechanics and for applications in biomaterials and drug development [1].

The mobility of filaments within these networks—their ability to move and reorganize—is crucial for understanding how cells maintain structural integrity while remaining adaptable. Recent research has revealed that this mobility depends nonmonotonically on the ratio of actin to tubulin, reaching a surprising maximum at equimolar ratios (ϕT = 0.5), where neither filament type dominates the network [1].

Key Experimental Findings

Table 1: Mechanical Properties Across Tubulin Fractions (ϕT) in Actin-Microtubule Composites

| Tubulin Fraction (ϕT) | Force Response | Strain Behavior | Relaxation Dynamics | Filament Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Actin only) | Low, homogeneous | Strain softening | Standard poroelastic | Baseline |

| 0.3 | Moderate | Strain softening | Enhanced poroelastic | Increasing |

| 0.5 (Equimolar) | High | Transition point | Fastest reptation | MAXIMUM |

| 0.7 | High, heterogeneous | Strain stiffening | Intermediate | Decreasing |

| 1 (Microtubules only) | Highest, heterogeneous | Strain stiffening | Slow reptation | Lowest |

Table 2: Force Relaxation Characteristics by Tubulin Fraction

| Tubulin Fraction (ϕT) | Short-time Relaxation (t < 0.06 s) | Long-time Relaxation | Scaling Exponent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Poroelastic + bending | Power-law decay | Lower |

| 0.3 | Enhanced poroelastic | Power-law decay | Increasing |

| 0.5 | Fast poroelastic | Power-law decay | HIGHEST |

| 0.7 | Suppressed bending | Power-law decay | Decreasing |

| 1 | Minimal bending | Power-law decay | Lowest |

The nonmonotonic dependence of mobility on tubulin fraction represents a significant finding for researchers optimizing these composite systems. At ϕT = 0.5 composites, both actin and microtubules display their highest mobility, with scaling exponents for long-time relaxation reaching maximum values. This suggests that reptation—the process where filaments diffuse curvilinearly out of their deformed tubular constraints—occurs most rapidly in equimolar composites [1].

This enhanced mobility arises from an optimal balance between mesh size constraints and filament rigidity. Actin reduces the composite mesh size, while microtubules provide structural reinforcement. At equimolar ratios, this balance allows for efficient stress relaxation through filament rearrangements without compromising network integrity [1].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Composite Preparation and Optimization

Protocol: Creating Co-Entangled Actin-Microtubule Composites

Protein Solution Preparation:

- Suspend varying ratios of unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers in aqueous buffer containing:

- 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.8)

- 2 mM MgCl₂

- 2 mM EGTA

- 2 mM ATP (required for actin polymerization)

- 1 mM GTP (required for tubulin polymerization)

- 5 μM Taxol (to stabilize microtubules against depolymerization)

- Final total protein concentration: 11.3 μM [1]

- Suspend varying ratios of unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers in aqueous buffer containing:

Fluorescent Labeling for Visualization:

- Add 0.13 μM pre-assembled Alexa-488-labeled actin filaments (1:1 labeled:unlabeled ratio)

- Add 0.19 μM pre-assembled rhodamine-labeled microtubules (1:5 labeling ratio)

- Limit labeled filaments to ~1% of total to enable resolution of single filaments within 3D networks [1]

Anti-bleaching Treatment:

- Incorporate oxygen scavenging system:

- 4.5 mg/mL glucose

- 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol

- 4.3 mg/mL glucose oxidase

- 0.7 mg/mL catalase [1]

- Incorporate oxygen scavenging system:

Polymerization Process:

- Incubate sample for 1 hour at 37°C

- Ensure isotropic, well-mixed networks without bundling, aggregation, or phase separation

- Verify filament lengths: actin 8.7 ± 2.8 μm; microtubules 18.8 ± 9.7 μm [1]

Microrheology Measurements

Protocol: Optical Tweezers Microrheology

Bead Preparation:

- Add sparse 4.5 μm diameter microspheres to composites before polymerization

- Coat beads with Alexa-488 BSA for surface compatibility

- Use beads at appropriate density to prevent interference [1]

Sample Chamber Setup:

- Pipette protein-bead mixture into chamber made from glass slide and coverslip

- Separate with ~100 μm spacer (double-sided tape)

- Seal with epoxy to prevent evaporation [1]

Force Measurement Parameters:

- Displace embedded microsphere 30 μm (exceeding filament lengths)

- Use displacement speed much faster than intrinsic relaxation rates

- Measure force exerted on bead and subsequent force relaxation

- Repeat across multiple regions to assess heterogeneity [1]

Experimental Workflow for Actin-Microtubule Composite Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Actin-Microtubule Studies

| Reagent | Function | Example Specifications | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Protein | Microtubule formation | Porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton T240) | Purified by assembly/disassembly cycles |

| Actin Protein | Actin filament formation | Rabbit skeletal actin (Cytoskeleton AKL99) | >99% purity, lyophilized |

| Fluorescent Tubulin | Microtubule visualization | Rhodamine-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton TL590M) | 1:5 labeling ratio for imaging |

| Fluorescent Actin | Actin visualization | Alexa-488-labeled actin (Thermo Fisher A12373) | 1:1 labeled:unlabeled for tracing |

| Taxol/Paclitaxel | Microtubule stabilization | 5-20 μM working concentration | Prevents depolymerization |

| Nucleotides | Polymerization energy | ATP (actin), GTP (microtubules) | 1-2 mM in buffer systems |

| Optical Tweezers Beads | Microrheology probes | 4.5 μm diameter microspheres | Coated with BSA for biocompatibility |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Researchers

Q1: Our composites show heterogeneous force responses, particularly at high tubulin fractions (ϕT > 0.7). How can we improve consistency?

A: Heterogeneous force response at high tubulin fractions indicates microtubule dominance without sufficient actin support. To resolve:

- Ensure proper co-polymerization by verifying both proteins polymerize under your buffer conditions

- Increase actin fraction to at least ϕT = 0.5 to reduce mesh size and provide lateral support to microtubules

- Confirm microtubule lengths are consistent (18.8 ± 9.7 μm) and not excessively long

- Check that incubation conditions (37°C, 1 hour) are precisely maintained throughout the sample [1]

Q2: We're having difficulty achieving reproducible equimolar (ϕT = 0.5) composites with optimal mobility. What critical factors should we check?

A: The nonmonotonic mobility peak at ϕT = 0.5 requires precise conditions:

- Verify total protein concentration is exactly 11.3 μM

- Confirm nucleotide concentrations (2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP) are fresh and properly balanced

- Ensure Taxol concentration is precisely 5 μM for microtubule stabilization without affecting polymerization kinetics

- Check that fluorescent tracer filaments constitute only ~1% of total filaments to avoid structural alterations

- Validate that networks are truly isotropic without flow alignment during sample loading [1]

Q3: Our force relaxation measurements don't show the expected power-law decay. What could be affecting our relaxation profiles?

A: Several factors can disrupt proper relaxation measurement:

- Ensure bead displacement distance is sufficient (30 μm, exceeding filament lengths)

- Verify displacement speed is faster than system relaxation rates

- Check that measurement timescales capture both short-time (t < 0.06 s) and long-time relaxation regimes

- Confirm that environmental vibrations aren't interfering with sensitive force measurements

- Validate that oxygen scavenging system is functional to prevent photodamage during extended measurements [1]

Q4: How can we distinguish between poroelastic relaxation and reptation in our composite systems?

A: The two relaxation mechanisms operate at different timescales:

- Poroelastic relaxation: Dominates at short times (t < 0.06 s), involves filament network rearrangements and water movement

- Reptation: Controls long-time relaxation, involves filaments diffusing out of entanglement constraints

- Identify the transition point in your relaxation curves, typically around 0.06 seconds

- Analyze scaling exponents for power-law decay, which reach maximum at ϕT = 0.5 for reptation

- Compare across different ϕT values - poroelastic relaxation accelerates while bending fluctuations are suppressed as tubulin fraction increases [1]

Q5: What alternative methods can we use to verify filament mobility beyond optical tweezers?

A: Complementary approaches include:

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) on labeled filament segments

- Single Particle Tracking of fiduciary markers within the network

- Bulk rheology to correlate macroscopic properties with microscopic mobility

- Magnetic tweezers as described in [14] for different force regimes

- Confocal microscopy with time-lapse analysis of network reorganization [1] [14]

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Problems

Advanced Applications and Research Directions

The unique properties of actin-microtubule composites, particularly the nonmonotonic mobility dependence, open several promising research directions:

Drug Screening Applications: These composites provide a physiologically relevant model for screening cytoskeleton-targeting drugs, including chemotherapeutic agents that specifically target microtubules or experimental compounds affecting cytoskeletal dynamics.

Biomaterial Development: The tunable mechanical properties of composites make them ideal scaffolds for tissue engineering, where balanced stiffness and adaptability are required for cell growth and differentiation.

Neurological Research: The compositional balance in cytoskeletal networks may inform understanding of neurodegenerative diseases where cytoskeletal disruptions occur, potentially enabling development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The optimization of actin-microtubule composites represents a significant advancement in biomimetic materials, with the equimolar ratio (ϕT = 0.5) serving as a critical reference point for researchers designing experiments in this field. The maximal mobility at this specific ratio underscores the importance of balanced composition in achieving optimal dynamic properties in cytoskeletal model systems.

Protocols for Reconstituting Active Composites: From Basic Networks to Motor-Driven Systems

Optimized Buffer Conditions for Co-Polymerizing Actin and Tubulin In Situ

Co-polymerizing actin and tubulin in situ creates composite networks that replicate aspects of the cellular cytoskeleton, enabling the study of emergent mechanical properties and filament interactions. These co-entangled networks exhibit unique characteristics not found in single-filament systems, including tunable viscoelasticity and coordinated dynamics. Proper buffer formulation is paramount for successful simultaneous polymerization, as it must satisfy the distinct biochemical requirements of both actin and tubulin while promoting the formation of isotropic, well-integrated networks without phase separation or aberrant structures [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical buffer components for successful co-polymerization?

The buffer must contain nucleotides for both filament systems (ATP for actin, GTP for tubulin), appropriate buffering agents, stabilizing agents for microtubules, and salts that support both polymerization processes simultaneously [1].

Q2: How can I verify that both networks have properly polymerized and are well-integrated?

Successful co-polymerization can be confirmed using fluorescence microscopy with differentially labeled actin and microtubule tracer filaments. Well-integrated composites appear as isotropic networks without visible bundling, aggregation, or phase separation when imaged [1].

Q3: What is the optimal incubation time and temperature for co-polymerization?

The established protocol specifies incubation for 1 hour at 37°C to ensure complete polymerization of both filament types under the hybrid buffer conditions [1].

Q4: How does the molar ratio of actin to tubulin affect composite mechanics?

The mechanical properties display a non-monotonic dependence on composition. Composites with ϕT = 0.5 (equimolar ratios) exhibit maximal filament mobility and unique relaxation dynamics, while higher microtubule fractions (ϕT > 0.7) are needed to substantially increase resistive forces [1].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Incomplete or Failed Polymerization of One Filament Type

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient nucleotides | Check ATP/GTP concentrations and freshness | Prepare fresh nucleotide stocks; ensure final concentrations: 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP [1] |

| Improper cation balance | Test single-component controls | Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (2 mM recommended); ensure no chelators interfere [1] |

| Component incompatibility | Polymerize each system separately | Use hybrid buffer specifically optimized for co-polymerization [1] |

Problem: Network Heterogeneity or Phase Separation

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Filament bundling | Inspect via fluorescence microscopy | Include oxygen scavengers to reduce photobleaching during imaging: 4.5 mg/mL glucose, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol, 4.3 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.7 mg/mL catalase [1] |

| Non-isotropic structures | Check for nematic domains | Optimize polymerization conditions; ensure proper pH (6.8) and buffer composition [1] |

| Microtubule instability | Verify Taxol concentration | Use 5 μM Taxol for microtubule stabilization; confirm proper temperature control [1] |

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Preparations

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein quality variability | Check polymerization efficiency of individual protein batches | Use high-purity proteins from reliable suppliers; follow proper storage and handling [1] |

| Inconsistent filament lengths | Measure filament size distributions | Standardize preparation methods; actin: 8.7 ± 2.8 μm, microtubules: 18.8 ± 9.7 μm [1] |

| Temperature fluctuations | Monitor incubation temperature closely | Use precise temperature control at 37°C throughout polymerization [1] |

Optimized Buffer Formulation and Protocol

Complete Buffer Composition for Actin-Tubulin Co-Polymerization

| Component | Final Concentration | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PIPES | 100 mM | Primary buffering agent, optimal pH range [1] |

| MgCl₂ | 2 mM | Essential cation for both polymerization processes [1] |

| EGTA | 2 mM | Calcium chelation, prevents destabilization [1] |

| ATP | 2 mM | Actin polymerization nucleotide requirement [1] |

| GTP | 1 mM | Microtubule polymerization nucleotide requirement [1] |

| Taxol | 5 μM | Microtubule stabilization [1] |

| pH | 6.8 (with KOH) | Optimal for both filament systems [1] |

Quantitative Network Parameters Across Compositions

| Tubulin Molar Fraction (ϕT) | Mesh Size Relationship | Mechanical Behavior | Relaxation Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Actin only) | ξA = 0.3/√cA (μm) | Strain softening | Standard reptation |

| 0.5 (Equimolar) | Intermediate mesh size | Transition behavior | Maximal reptation scaling exponents [1] |

| 1 (Microtubules only) | ξM = 0.89/√cT (μm) | High force response | Limited relaxation |

| >0.7 (High MT) | Dominated by microtubules | Strain stiffening | Faster poroelastic relaxation [1] |

Note: cA and cT are protein concentrations in mg/mL; mesh sizes in microns [1]

Experimental Workflow for Co-Polymerization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for creating and analyzing actin-microtubule composites:

Step-by-Step Protocol

Buffer Preparation: Combine all buffer components except nucleotides and Taxol in ultrapure water. Adjust pH to 6.8 with KOH, then add ATP, GTP, and Taxol from fresh stock solutions [1].

Protein Mixture: Combine unlabeled actin monomers and tubulin dimers in the desired molar ratio (ϕT = [tubulin]/([actin]+[tubulin])) in the complete buffer. For visualization, include minimally labeled tracer filaments (~1% of total) [1].

Co-polymerization: Transfer mixture to observation chamber and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour. Maintain stable temperature throughout polymerization [1].

Quality Assessment: Verify network formation and structure using fluorescence microscopy. Well-formed composites appear isotropic without bundling or phase separation [1].

Mechanical Characterization: Employ optical tweezers microrheology or bulk rheology to quantify mechanical response. Bead displacement experiments can probe nonlinear mechanics [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified tubulin dimers | Microtubule polymerization | Porcine brain source; 5 mg/mL stock; prevent aggregation [1] [15] |

| Skeletal muscle actin | Actin filament formation | Rabbit skeletal source; polymerize with ATP [1] [15] |

| Taxol (paclitaxel) | Microtubule stabilization | 5 μM final concentration; add after polymerization [1] |

| Fluorescently labeled tracers | Network visualization | Alexa-488 actin, rhodamine tubulin; use ~1% labeling ratio [1] |

| Oxygen scavenging system | Photobleaching prevention | Glucose oxidase/catalase system for prolonged imaging [1] |

Successful co-polymerization of actin and tubulin in situ requires precise optimization of buffer conditions that balance the distinct biochemical requirements of both filament systems. The established protocol using 100 mM PIPES pH 6.8, 2 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, and 5 μM Taxol, with incubation at 37°C for 1 hour, reliably produces isotropic, well-integrated composites. Systematic variation of the actin-to-tubulin molar ratio (ϕT) enables tuning of mechanical properties, with equimolar composites (ϕT = 0.5) exhibiting unique emergent behaviors including enhanced filament mobility and distinctive relaxation dynamics. These co-entangled networks provide valuable model systems for studying cytoskeletal interactions and designing biomimetic materials.

In the reconstitution of actin-microtubule co-entangled networks, non-specific adsorption of proteins to glass surfaces is a major experimental challenge. Such adsorption can deplete crucial proteins from the reaction chamber, alter network biochemistry, and impede the formation of homogeneous, three-dimensional composite structures [16] [17]. Silanization creates a hydrophobic barrier on glass surfaces, preventing proteins from sticking and thereby ensuring that the assembly and dynamics of cytoskeletal composites occur in the bulk solution as intended. This guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting for effective surface preparation, a critical step for researchers aiming to optimize the study of composite cytoskeletal mechanics and active matter.

Core Experimental Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol is adapted from established methods for preparing surfaces for cytoskeletal reconstitution [16] [17].

Materials and Equipment

- Coverslips and Slides: No. 1 coverslips (24 mm x 24 mm) and microscope slides (1 in x 3 in).

- Cleaning Agents: 100% Acetone, 100% Ethanol, Deionized (DI) Water, 0.1 M Potassium Hydroxide (KOH).

- Silanization Reagent: 2% silane (e.g., allyltrichlorosilane) dissolved in Toluene [16] [18].

- Equipment: Plasma cleaner, glass containers and racks, fume hood, vacuum oven or standard oven.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part 1: Thorough Cleaning of Glass Surfaces

- Objective: Remove all organic contaminants and enhance surface hydroxyl groups for uniform silane binding.

- Steps:

- Plasma Cleaning: Place coverslips and slides in a rack and treat in a plasma cleaner for 20 minutes [16] [17].

- Solvent Rinsing: Transfer the glass to a dedicated silanization rack and immerse in the following solutions in sequence [16] [17]:

- 100% Acetone for 1 hour.

- 100% Ethanol for 10 minutes.

- DI Water for 5 minutes.

- Repeat this solvent rinse cycle two more times for a total of three cycles.

- Base Cleaning: Immerse the glass in freshly prepared 0.1 M KOH for 15 minutes, then rinse in fresh DI water for 5 minutes. Repeat this step two more times [16] [17].

- Drying: Air dry the cleaned coverslips and slides for 10 minutes [16] [17].

Part 2: Silanization to Create a Hydrophobic Barrier

- Objective: Covalently bond a silane monolayer to the glass, creating a protein-repellent surface.

- Steps (perform in a fume hood):

- Silane Application: Immerse the dried, cleaned glass in a 2% silane solution in toluene for 5 minutes [16] [17]. The silane solution can be reused up to five times.

- Washing: To remove unbound silane, wash the glass sequentially [16] [17]:

- Immerse in 100% ethanol for 5 minutes. Repeat with fresh ethanol.

- Immerse in fresh DI water for 5 minutes.

- Repeat the ethanol and DI water wash cycle two more times.

- Curing: Air dry the coverslips for 10 minutes. For increased stability, bake them in an oven at 60°C for 2 hours to dehydrate and cure the silane layer [16] [18].

- Storage: Store the silanized coverslips in a desiccator at room temperature. They remain effective for at least one month [16] [17].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein adsorption persists | Incomplete surface cleaning or silanization; unsuitable silane type. | Ensure rigorous cleaning with KOH. Consider using a dipodal silane (e.g., bis(trimethoxysilyl) species) for greatly enhanced hydrolytic stability [19]. |

| Network forms unevenly or appears patchy | Inconsistent silane layer due to contaminated glass or insufficient washing. | Use fresh, high-purity solvents. Ensure adequate washing steps post-silanization to prevent precipitate formation [16]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio in imaging | Biomolecule loss from surface over long incubations. | Functionalize surfaces with dipodal silanes, which can improve signal-to-noise ratios by 2- to 4-fold compared to standard monopodal silanes [19]. |

| Actin-microtubule networks rupture or show disordered flow | Inadequate surface passivation leading to aberrant network anchoring and mechanics. | Verify silanization success via water contact angle test. Ensure myosin II is properly activated and that actin/microtubule concentrations are comparable (e.g., 2.9 µM each) for optimal composite integrity [9] [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is silanization specifically critical for actin-microtubule composite studies? These experiments require precise control over protein concentrations and network architecture. Silanization prevents the depletion of actin, tubulin, and motor proteins from the solution, which is essential for forming well-mixed, co-entangled networks that exhibit emergent properties like coordinated contractility and enhanced connectivity [9] [1].

Q2: My composite network is still contracting unevenly. Could the surface be the issue? Yes. Even partial protein adsorption can create unintended anchors, leading to heterogeneous force transmission. Verify your silanization protocol is followed exactly. Furthermore, research shows that actin networks alone exhibit disordered flow and rupturing, while composite actin-microtubule networks show organized contraction. Ensure your protein fractions are correct (e.g., equimolar actin/tubulin) to achieve the stabilizing effect of microtubules [9].

Q3: Are there alternatives to the silane mentioned in the protocol? Yes. While allyltrichlorosilane and similar monopodal silanes are common, recent studies demonstrate that dipodal silanes (e.g., those with two silicon anchoring points) form surfaces with greatly superior resistance to hydrolysis during warm, long-term aqueous incubations, leading to higher biomolecule retention and better data quality [19].

Q4: How can I validate that my coverslips are properly silanized? A simple qualitative test is to check the water contact angle. A successfully silanized hydrophobic surface will cause a water droplet to bead up, while a clean hydrophilic glass surface will cause the droplet to spread completely.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the featured protocols for silanization and subsequent cytoskeletal composite assembly.

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example or Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Allyltrichlorosilane | Monopodal silane used to create a hydrophobic monolayer on glass to prevent protein adsorption. | Merck MilliporeSigma #107778 [18] |

| Dipodal Silanes | Silanes with two anchor points for enhanced surface stability and biomolecule retention during long assays. | e.g., 1,11-bis(trimethoxysilyl)-4-oxa-8-azaundecan-6-ol [19] |

| Triethylamine | Base catalyst used in some silanization solutions to promote the reaction. | [18] |

| Phalloidin | Small molecule used to stabilize actin filaments and prevent depolymerization in composite networks. | Used at a 2:1 actin:phalloidin molar ratio [16] [17] |

| Taxol (Paclitaxel) | Pharmaceutical agent used to stabilize microtubules against depolymerization in composites. | Used at 5-200 µM in polymerization buffers [16] [1] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the silanization protocol and its role in the broader context of cytoskeletal research.

Fluorescence Labeling Strategies for Multi-Spectral Confocal Imaging

For researchers investigating complex biological systems like actin-microtubule co-entangled networks, multi-spectral confocal imaging provides a powerful tool to visualize interactions and dynamics. However, the successful application of this technology relies heavily on appropriate fluorescent labeling strategies that address challenges such as spectral bleed-through, autofluorescence, and non-specific staining. This technical support center addresses the most common experimental hurdles and provides optimized protocols to ensure high-quality, reliable data for your cytoskeleton research.

FAQs: Core Concepts in Multi-Spectral Labeling

What is the primary advantage of spectral confocal microscopy over conventional fluorescence imaging?

Spectral confocal microscopy captures the entire emission spectrum at each image pixel, unlike conventional systems that use fixed optical filters. This enables linear unmixing algorithms to distinguish multiple fluorophores with highly overlapping spectra, even when they are present in the same pixel. This dramatically increases the number of targets that can be imaged simultaneously—a technique known as high-plex imaging [20] [21] [22].

Why is spectral bleed-through a critical issue, and how can it be minimized?

Spectral bleed-through occurs when the emission of one fluorophore is detected in the channel reserved for another, due to the broad and asymmetrical emission spectra of most fluorophores. This can lead to false co-localization data [23]. To minimize it:

- Choose spectrally well-separated fluorophores [24] [23].

- Balance fluorophore concentrations so that a bright signal from one dye does not overwhelm a weaker signal from another [23].

- Use sequential scanning instead of simultaneous scanning when acquiring images for multiple channels [23].

- Employ spectral unmixing to computationally separate the signals after acquisition [22].

How can I reduce high background autofluorescence in tissue samples, such as in cytoskeleton networks?

Autofluorescence is a common source of background, particularly in the blue/green wavelengths [24].

- Use far-red or near-infrared fluorescent probes to avoid autofluorescence-rich spectral regions [20] [24].

- Incorporate heparin blocking during sample preparation to reduce charge-based off-target binding [20].

- Apply commercial autofluorescence quenchers, such as TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher, after staining but before imaging [24].

- Acquire an autofluorescence reference spectrum from an unlabeled sample and subtract it computationally during linear unmixing [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: No Staining or Weak Fluorescence Signal

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Low antibody concentration | Titrate the primary and secondary antibodies to find the optimal concentration. A good starting point is 1 μg/mL for primary antibodies [24]. |

| Intracellular target inaccessibility | Confirm the subcellular localization of your target. For intracellular epitopes, you may need to use permeabilization protocols [24]. |

| Photobleaching during imaging | Use an antifade mounting medium. Select photostable dyes, such as rhodamine-based compounds, and avoid blue fluorescent dyes like CF350 for prolonged imaging [24]. |

| Incompatible imaging settings | Verify that the microscope's excitation laser and emission detection settings are correct for your chosen fluorophores [24]. |

Problem 2: High Background or Non-Specific Staining

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Tissue or cell autofluorescence | Include an unstained control. Use autofluorescence quenchers and shift to longer-wavelength dyes [24]. |

| Secondary antibody cross-reactivity | Use highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies. Perform a control stain with the secondary antibody alone to check for non-specific binding [24]. |

| Antibody concentration too high | Titrate antibodies to find the concentration that maximizes signal-to-noise. High concentrations can increase background [24]. |

| Charge-based off-target binding | Use specialized blocking buffers (e.g., TrueBlack IF Background Suppressor) and incorporate heparin into your blocking step to minimize ionic interactions [20] [24]. |

Problem 3: Spectral Bleed-Through Between Channels

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal fluorophore selection | Choose dye combinations with minimal spectral overlap. Use online tools like FluoroFinder's Spectra Viewer to design optimal panels [22] [24]. |

| Unbalanced fluorophore intensity | Label less abundant targets with the brightest and most photostable fluorophores. Adjust the relative labeling concentrations during specimen preparation [23]. |

| Insufficient unmixing | Ensure you acquire high-quality reference spectra from singly-labeled control samples for each fluorophore. These are essential for accurate linear unmixing [21] [22]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Spectral Live-Cell Imaging of Cytoskeletal Elements

This protocol enables the simultaneous visualization of up to six cellular components, adapted for studying actin-microtubule composites [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| abberior LIVE Tubulin & Actin labels | Cell-permeable dyes for specific labeling of microtubules and actin filaments in living cells [25]. |

| Verapamil | Efflux pump inhibitor; prevents cells from actively removing the dye, improving signal retention [25]. |

| Fibronectin | Coats glass surfaces to improve cell adhesion during live imaging [21]. |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Transfection reagent for introducing plasmid DNA encoding fluorescent proteins (e.g., mApple-SiT for Golgi) [21]. |

| Plasmids: CFP-LAMP1, Mito-EGFP, etc. | Genetically encoded fluorescent probes for targeting specific organelles like lysosomes and mitochondria [21]. |

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Coat 8-well chambered slides with 10 μg/mL fibronectin in PBS for 15-20 minutes at room temperature. Aspirate before plating cells [21].

- Cell Seeding and Transfection: Plate adherent cells (e.g., Cos-7) at an appropriate density (e.g., 1.5x10⁴ cells/well). Transfert with organelle-specific fluorescent protein constructs as needed [21].

- Staining Solution Preparation: On the day of imaging, dissolve abberior LIVE dyes in DMSO to create a 1 mM stock. Dilute this stock in pre-warmed live-cell imaging medium to a final concentration between 0.01 and 1 μM. Add Verapamil to a final concentration of 1-25 μM [25].

- Cell Staining: Remove the culture medium from cells and rinse with pre-warmed imaging medium. Replace with the staining solution and incubate for 30-60 minutes under optimal growth conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) [25].

- Image Acquisition: For live-cell imaging, a washing step is optional due to the low nanomolar dye concentrations used. Replace the staining solution with fresh imaging medium. Image directly on a confocal microscope equipped with a spectral detector and an environmental chamber maintained at 37°C and 5% CO₂ [21] [25].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Reconstitution of Actin-Microtubule Coupling

This TIRF microscopy-based protocol allows for the visualization of dynamic interactions between individual actin filaments and microtubules in a minimal system [26].

Procedure:

- Coverslip Preparation: Clean #1.5 high-quality glass coverslips by sonicating in ddH₂O with a drop of dish soap, followed by 0.1 M KOH. Store in ethanol [26].

- PEG-Coating: Dissolve mPEG-silane (2 mg/mL) and biotin-PEG-silane (0.04 mg/mL for sparse coating) in 80% ethanol (pH 2.0). Coat cleaned coverslips with this solution and incubate at 70°C for at least 18 hours [26].

- Flow Chamber Assembly: Assemble a flow chamber by attaching a PEG-coated coverslip to a microscope slide using double-sided tape, creating a channel. Seal the ends with epoxy [26].

- Chamber Conditioning: Use a perfusion pump or pipette to sequentially flow through the chamber:

- 50 μL of 1% BSA to prime the surface.

- 50 μL of 0.005 mg/mL streptavidin. Incubate 1-2 min.

- 50 μL of 1% BSA to block.

- 50 μL of warm TIRF buffer (BRB80, KCl, DTT, glucose, methylcellulose) [26].

- Polymerization and Imaging: Introduce a solution containing actin monomers, tubulin dimers, ATP, GTP, and regulatory proteins (e.g., Tau). Maintain the chamber at 35-37°C on a TIRF microscope. Acquire images every 5 seconds for 15-20 minutes using 488 nm (for microtubules) and 647 nm (for actin) lasers [26].

Data Presentation: Fluorophore Selection Table

Selecting fluorophores with well-separated emission peaks is critical for successful multi-spectral imaging. The following table provides a comparison of common fluorophores and proteins, based on data from the search results.

| Fluorophore/Protein | Peak Excitation (nm) | Peak Emission (nm) | Recommended Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP / Cerulean | ~433 [21] | ~475 [21] | Organelle labeling [21] | Good for live cells; avoid 405 nm laser due to phototoxicity [21]. |

| EGFP | ~488 [21] | ~507 [21] | General protein fusion [21] | Bright and widely used; high crosstalk potential with YFP. |

| YFP / Venus | ~514 [21] | ~527 [21] | Organelle labeling [21] | Bright; requires spectral unmixing to separate from EGFP [21]. |

| mOrange2 | ~549 [21] | ~565 [21] | Organelle labeling [21] | Useful for expanding the color palette into orange wavelengths. |

| Alexa Fluor 594 | ~590 [23] | ~617 [23] | Immunofluorescence | Well-separated from Alexa Fluor 488, minimizing bleed-through [23]. |

| mApple | ~562 [21] | ~592 [21] | Organelle labeling [21] | |

| Alexa Fluor 633 | ~632 [23] | ~647 [23] | Immunofluorescence | Excellent separation from Alexa Fluor 488; minimal bleed-through [23]. |

| BODIPY 665/676 | ~665 [21] | ~676 [21] | Vital dye for lipid droplets [21] | Far-red dye, helps avoid autofluorescence. |

The relationship between excitation, emission, and the problem of bleed-through is visualized in the following diagram.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Myosin II-Driven Actin-Microtubule Network Contraction

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered actin contraction & rupturing | Lack of sufficient network connectivity/cross-linking. | Incorporate microtubules (equal molar ratio to actin) to provide flexural rigidity and enhanced connectivity. | [9] |

| Uncontrolled, fast contraction speed | High myosin activity in pure actin networks. | Introduce microtubules to slow actomyosin activity and enable more controlled, sustained contraction. | [9] |