Microtubule Lattice Dynamics: From Structural Heterogeneity to Clinical Translation

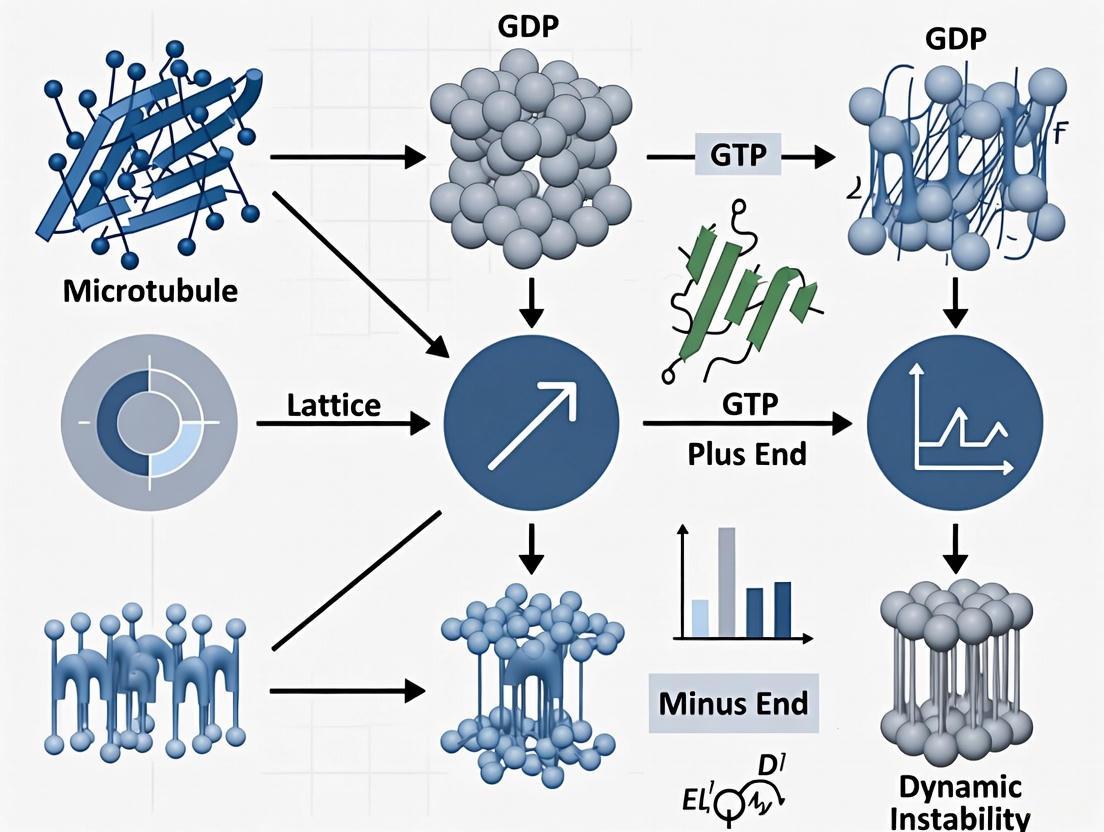

This article synthesizes recent breakthroughs in understanding microtubule lattice dynamics, moving beyond the traditional view of a static microtubule shaft.

Microtubule Lattice Dynamics: From Structural Heterogeneity to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes recent breakthroughs in understanding microtubule lattice dynamics, moving beyond the traditional view of a static microtubule shaft. We explore the foundational concepts of lattice heterogeneity, including seams and topological defects, and detail cutting-edge characterization methods like segmented subtomogram averaging and super-resolution microscopy. The review further examines how microtubule-associated proteins and drugs modulate lattice stability and turnover, and provides a critical comparison of in vitro versus cellular assays for drug development. Finally, we discuss the translational implications of lattice dynamics in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer therapy, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Beyond the Static Shaft: Unveiling Lattice Heterogeneity and Intrinsic Dynamics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the two primary lattice types in microtubules, and which one is predominant in cytoplasmic microtubules? Microtubules can form two distinct lattice types: the A-lattice and the B-lattice. In the A-lattice, α-tubulin subunits are situated adjacent to β-tubulin subunits on neighboring protofilaments. In the B-lattice, the more common type, α-tubulin lies beside α-tubulin, and β-tubulin beside β-tubulin [1]. Research using cryo-electron tomography on cytoplasmic microtubules from mammalian cells has confirmed that the B-lattice is the predominant arrangement in vivo [1]. However, because microtubules with 13 protofilaments and a B-lattice cannot close into a perfect cylinder, they contain a single structural discontinuity called a "seam," where the tubulin subunits interact in an A-lattice configuration [2] [1].

Q2: My experiments on lattice spacing are yielding inconsistent results. What factors could be regulating this spacing? The microtubule lattice spacing, or dimer rise, is not static but a dynamic property regulated by several competing factors. Your results may vary due to:

- Nucleotide State: GTP-bound tubulin tends to form an expanded lattice (83.5 Ã…), while GDP-bound tubulin typically forms a compacted lattice (81.7 Ã…) [3].

- MAP Binding: Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) can directly influence spacing. For example, kinesin-1 acts as a lattice expander, while doublecortin (DCX) acts as a compactor [3].

- Pharmacological Agents: Drugs like paclitaxel stabilize and expand the microtubule lattice [3].

- Mechanical Forces: Bending or compressive forces can compress the lattice on the inner curve of a bend and expand it on the outer curve [3]. The observed lattice state in an experiment is often the result of the local balance between these expanding and compacting forces [3].

Q3: How does the neuronal protein tau affect microtubule lattice dynamics, beyond simple stabilization? Historically viewed as a passive stabilizer, tau is now known to actively modulate the microtubule lattice. Although it stabilizes microtubules against catastrophic fracture [4], tau surprisingly accelerates the exchange of tubulin dimers within the lattice itself [4]. This exchange occurs preferentially at topological defect sites. Tau achieves this by increasing lattice anisotropy—it stabilizes longitudinal tubulin-tubulin interactions while destabilizing lateral ones. This promotes the mobility and annihilation of lattice defects, effectively enabling the lattice to self-repair [4].

Q4: What is the functional significance of the microtubule seam? The seam is a unique long-range structural defect where the typical B-lattice transitions into an A-lattice. This break in helical symmetry means the microtubule is not a perfectly cylindrical structure and has two distinct faces [1]. This structural uniqueness has functional consequences; the seam can serve as a specific binding site for certain MAPs. For instance, the End-Binding protein EB1 has been shown to bind preferentially along the seam, which may help stabilize the microtubule structure in a specific orientation [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Uninterpretable Kymographs from Microtubule Dynamics Assays

Problem: Kymographs show blurry or inconsistent microtubule trajectories, making it difficult to measure growth speeds or catastrophe frequencies.

Solution:

- Verify Preparation of Labelled Tubulin: Ensure the fluorescent tubulin is functional and free of aggregates. Use ultracentrifugation (e.g., at 100,000 x g for 10 minutes) to pellet aggregates immediately before use.

- Optimize Imaging Conditions: Reduce background noise by using TIRF microscopy. Shorten exposure times and increase laser intensity to "freeze" dynamic ends, but be mindful of photobleaching and phototoxicity.

- Confirm Assay Buffer Health: Ensure an adequate GTP-to-tubulin ratio (typically >1:1) and include an oxygen-scavenging system (e.g., glucose oxidase/catalase) and a triplet-state quencher (e.g., Trolox) to prolong filament and fluorophore longevity.

- Positive Control: Validate your entire workflow by reproducing a well-established result, such as the acceleration of microtubule growth by XMAP215/CLASP family proteins.

Issue 2: Failure to Recapitulate Lattice Spacing Phenomena from Literature

Problem: In vitro experiments with MAPs like DCX or drugs like paclitaxel do not produce the expected changes in microtubule lattice spacing or organization.

Solution:

- Re-check Protein Purification and Activity: Confirm that your recombinant MAP is purified, folded correctly, and is active in a standard microtubule co-sedimentation (pull-down) assay.

- Titrate Critical Components: The effect on lattice spacing is highly concentration-dependent. Systematically titrate both the MAP (e.g., DCX) and the drug (e.g., paclitaxel), as their influence is competitive [3]. A high concentration of a compactor like DCX can counteract the expanding effect of paclitaxel [3].

- Control Nucleotide State: Use non-hydrolysable GTP analogues (e.g., GMPCPP) to create purely expanded lattices or GDP with specific salts to create compacted lattices as baseline controls for your assays [3].

- Use a Sensitive Readout: If direct cryo-EM is not feasible, employ an indirect functional assay. For example, monitor the re-localization of a GFP-tagged compactor like DCX in cells upon paclitaxel treatment, as its binding is lattice-spacing-dependent [3].

Issue 3: High Background in Tubulin Lattice Incorporation Assays

Problem: Excessive fluorescent background obscures the specific signal from tubulin dimers incorporated into the microtubule lattice.

Solution:

- Refine Wash Steps: After incubating with fluorescent tubulin, implement rigorous wash procedures. Use multiple flows of warm assay buffer (at least 5-10 chamber volumes) to remove unincorporated tubulin dimers thoroughly.

- Optimize Concentrations: Reduce the concentration of free fluorescent tubulin during the incorporation phase. The goal is to favor incorporation at lattice defect sites over spontaneous nucleation in solution. Test concentrations in the range of 5-10 µM [4].

- Include a Capping Agent: To prevent incorporation at the microtubule ends from dominating the signal, cap the ends with stable, unlabeled GMPCPP seeds or a plus-end-binding protein that inhibits growth [4].

- Confirm Microtubule Stabilization: Ensure the "stable" microtubule seeds are genuinely inert. Polymerize seeds with GMPCPP and verify their stability by imaging over time in the absence of free tubulin.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Experimentally Observed Microtubule Lattice Spacing

This table summarizes key quantitative measurements of microtubule lattice spacing under different conditions, crucial for interpreting structural data.

| Nucleotide State / Condition | Lattice Spacing (Å, mean ± SEM) | Lattice Conformation | Primary Experimental Method | Key Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTP-like State (GMPCPP) | 83.5 ± 0.2 | Expanded | Cryo-EM | [3] |

| GDP State (in vitro) | 81.7 ± 0.1 | Compacted | Cryo-EM | [3] |

| + Microtubule Expander (e.g., Kinesin-1) | ~83.5 | Expanded | Light Microscopy / Cryo-EM | [3] |

| + Microtubule Compactor (e.g., DCX) | ~81.7 | Compacted | Cryo-EM / X-ray Diffraction | [3] |

Table 2: Quantifying the Impact of Tau on Microtubule Lattice Dynamics

This table presents quantitative data on how the MAP tau influences tubulin exchange and mechanical integrity of the microtubule lattice.

| Experimental Parameter | Control (0 nM Tau) | With 20 nM Tau | Change | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Tubulin Incorporation Length (after 15 min) | 0.7 µm | 1.2 µm | +71% | In vitro incorporation assay [4] |

| Spatial Frequency of Incorporation (median distance between events) | 12.4 µm | 6.6 µm | -47% | In vitro incorporation assay [4] |

| Overall Tubulin Incorporation (after 15 min) | 1x (baseline) | 4x | +300% | In vitro incorporation assay [4] |

| Lattice Fluorescence Loss at Incorporation Sites (after 30 min) | ~7% | ~15% | Increased loss | Indicates tubulin exchange, not just addition [4] |

| Microtubule Fracture Rate (in absence of free tubulin) | 1x (baseline) | Slower | Decreased | Enhanced mechanical stability [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Microtubule Lattice Type via Cryo-Electron Tomography

Objective: To directly visualize the lattice structure and identify the seam in cellular cytoplasmic microtubules.

Background: This protocol is adapted from studies that resolved the B-lattice structure of microtubules in mammalian cells [1]. It involves decorating microtubules with a motor protein to reveal the underlying tubulin dimer arrangement.

Materials:

- Cultured cells (e.g., 3T3 fibroblasts) grown on carbon-coated electron microscopy grids.

- Lysis/Permeabilization Buffer: 60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgClâ‚‚, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 6.9.

- Purified monomeric motor domain of Eg5 (kinesin-5).

- Liquid ethane for plunge-freezing.

- Cryo-electron microscope equipped with a tilting holder.

Method:

- Cell Lysis and Decoration: Quickly perfuse the lysis buffer containing ~0.1 mg/mL of the Eg5 motor domain over the cells on the grid for 20-30 seconds. This permeabilizes the cells while preserving microtubules and allows motor proteins to bind to them [1].

- Rapid Freezing: Blot the grid to remove excess liquid and immediately plunge-freeze it in liquid ethane to preserve the structure in a vitreous ice state.

- Tomographic Data Collection: Transfer the grid to the cryo-electron microscope. Collect a tilt-series of images (e.g., from -60° to +60° at 2° intervals) of cellular regions where microtubules span holes in the carbon film.

- Image Reconstruction and Analysis: Use software (e.g., IMOD) to align the tilt-series and reconstruct a 3D tomogram. Inspect the tomogram for the helical pattern of the bound motor heads. A single, paraxial seam and a pattern consistent with a B-lattice (where motors follow a left-handed, 1.5-start helix) confirm the predominant lattice structure [1].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Assay for Microtubule Lattice Spacing Competition

Objective: To investigate the competitive regulation of microtubule lattice spacing by a compactor (DCX) and an expander (paclitaxel).

Background: This assay, based on recent research, uses microtubule buckling as a readout for lattice spacing changes observable by light microscopy [3]. An expanded lattice will buckle more under constrained conditions.

Materials:

- Purified tubulin.

- Microtubule compactor protein (e.g., Doublecortin/DCX).

- Microtubule expander drug (e.g., Paclitaxel).

- Non-hydrolysable GTP analogue (GMPCPP).

- Flow chamber for microscopy.

- TIRF microscope.

Method:

- Form Double-Capped Microtubules: Polymerize microtubules with a central GDP-lattice segment capped at both ends by stable GMPCPP-lattice sections [3].

- Immobilize and Induce Compression: Anchor these microtubules to a coverslip surface. The inherent length difference between the GDP and GMPCPP lattices upon introduction to assay buffer will generate axial compression on the central GDP segment.

- Apply Test Conditions: Introduce the compactor (DCX) and/or expander (paclitaxel) at varying concentrations.

- Image and Quantify Buckling: Use TIRF microscopy to record microtubule behavior. The frequency and amplitude of buckling events in the central segment serve as a proxy for lattice expansion. For example, high paclitaxel concentrations should induce more buckling (expansion), which can be suppressed by sufficiently high concentrations of DCX (compaction) [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microtubule Lattice Characterization

| Reagent Name | Function / Description | Key Application in Lattice Research |

|---|---|---|

| GMPCPP (Guanylyl-(α,β)-methylene-diphosphonate) | A non-hydrolysable GTP analog that stabilizes microtubules in a GTP-like, expanded lattice state [3] [4]. | Creating stable seeds for polymerization; studying expanded lattice structure and dynamics. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | A small molecule drug that binds and stabilizes microtubules, promoting an expanded lattice conformation [3]. | A tool to experimentally induce and study expanded lattice states; used in competition experiments with compactors. |

| Doublecortin (DCX) | A neuronal Microtubule-Associated Protein (MAP) that functions as a lattice compactor, stabilizing a compacted state [3]. | A tool to experimentally induce and study compacted lattice states; used to investigate competition for lattice spacing control. |

| Tau Protein (e.g., 2N4R isoform) | A neuronal MAP that stabilizes microtubules but accelerates tubulin exchange within the lattice, facilitating defect repair [4]. | Studying lattice dynamics, self-repair mechanisms, and the role of MAPs beyond simple stabilization. |

| Kinesin-1 Motor Domain | A molecular motor that binds processively to microtubules and can act as a lattice expander [3]. | Probing lattice state (expanded vs. compacted); studying the interplay between motor proteins and lattice structure. |

| Monomeric Eg5 Motor Domain | A kinesin motor domain that binds densely to the microtubule lattice without processive movement, decorating the underlying tubulin arrangement [1]. | A marker for visualizing the helical tubulin lattice and identifying the seam in structural studies (e.g., cryo-ET). |

Signaling Pathways & Workflow Diagrams

Tau-Mediated Lattice Repair

Lattice Spacing Competition

The Role of Seams and Multi-Seam Structures in Lattice Integrity

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a microtubule lattice seam, and why is it important for researchers to identify? A lattice seam is a structural discontinuity in the microtubule wall where protofilaments associate via heterotypic (α-β) lateral contacts, unlike the homotypic (α-α or β-β) contacts found in the rest of the B-lattice [5]. Accurately determining its location is critical because it breaks the helical symmetry, and misidentification can lead to incorrect modeling of key functional regions, such as the nucleotide state at the E-site in β-tubulin and the geometry of lateral contacts [5]. For dynamic instability studies, the seam can act as a trigger point for catastrophe [6].

Q2: Our cryo-EM processing of microtubules is failing to reach a consensus on seam location. What could be the cause and solution? This is common when the marker protein used for registration is relatively small or its decoration is sparse [5]. Traditional projection-matching methods can fail under these conditions. A solution is to implement a specialized seam-search protocol that leverages the intrinsic ~80 Å tubulin dimer repeat signal in the raw images, which can help determine the αβ-tubulin register even without a large marker [5].

Q3: We are observing unusually high shrinkage rates and catastrophe frequency in our microtubule assays. Could the lattice structure be a factor? Yes. Experimental evidence shows that microtubules with extra A-lattice seams are significantly destabilized. For example, GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules with enriched A-lattice content shrink at a median rate over 20 times faster than their B-lattice counterparts [6]. Introducing multiple seams creates pre-existing pathways that accelerate damage propagation and destabilize the lattice [7].

Q4: How can we experimentally produce microtubules with defined seam numbers for comparative studies? While spontaneous in vitro assembly rarely produces such microtubules, you can use the S. pombe EB1 protein Mal3. Adding a high concentration of Mal3 during nucleation can drive the assembly of A-lattice-enriched 13-protofilament microtubules. It is crucial to remove Mal3 after assembly before stability assays, as lattice-bound Mal3 can itself stabilize microtubules [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable 3D Reconstructions | Incorrect initial helical parameters or seam location [5] | Perform multi-reference alignment against models with different protofilament numbers (e.g., 12-15 PFs) to determine initial parameters [5]. |

| Inability to Distinguish α/β-tubulin | Lack of a clear structural marker in cryo-EM images [5] | Employ a dedicated seam-search strategy that utilizes the tubulin dimer repeat signal, even with small marker proteins like EB's CH domain [5]. |

| High Catastrophe Frequency | Underlying lattice defects or multiple seams in seeds [6] | Verify the seam structure of nucleating seeds. Use B-lattice seeds with a single seam for more stable growth [6]. |

| Excessive Microtubule Shrinkage | A-lattice enriched structures destabilizing the lattice [6] | Control for seam content during polymerization. Assess shrinkage rates against a known B-lattice single-seam control [6]. |

| Microtubule Fracture/Damage | Low ratio of longitudinal to lateral binding energies; multiple seams [7] | Ensure proper buffer conditions. Be aware that simulations suggest the longitudinal/lateral binding energy ratio is bounded near 1.5 for stability [7]. |

Table 1: Impact of A-Lattice Seam Content on Microtubule Stability

This table summarizes key quantitative findings on how seam content influences microtubule dynamic instability, based on experimental data [6].

| Microtubule Type / Seed | A-Lattice Content | Median Shrinkage Rate (nm/s) | Catastrophe Frequency | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-lattice Single-seam | ~1 seam | 2.5 | Baseline (reference) | GMPCPP, pig brain tubulin [6] |

| A-lattice Enriched (Mal3-N143) | ~50% (avg.) | 22.6 | Increased | GMPCPP, assembled with monomeric Mal3-CH [6] |

| A-lattice Enriched (Mal3FL) | ~50% (avg.) | 58.8 | Increased | GMPCPP, assembled with dimeric full-length Mal3 [6] |

| Dynamic MTs (A-lattice seeds) | Multiple seams | Growth rate similar to B-lattice | Increased at both ends | Nucleated from A-lattice enriched seeds [6] |

Table 2: Key Measurements for Structural Analysis

This table outlines critical measurements for characterizing microtubule lattice structure, drawing parallels from precise seam inspection methodologies [8].

| Measurement | Description | Significance in Lattice Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Protofilament (PF) Number | The number of protofilaments forming the microtubule wall [5] | Defines the basic lattice type and curvature; influences mechanical strength [5]. |

| Seam Location | The specific protofilament interface with heterotypic (α-β) contacts [5] | Critical for correct helical symmetry imposition in 3D reconstruction [5]. |

| Lateral Contact Type | Geometry of interactions (B-lattice: α-α/β-β; Seam: α-β) [5] [6] | A-lattice contacts at seams may have different stability compared to B-lattice [6]. |

| Nucleotide State (E-site) | GTP vs. GDP in β-tubulin, visualized in high-res maps [5] | Directly reports on the stability of the microtubule; GDP-core is unstable [5] [6]. |

| Body Wall Thickness | The physical thickness of the polymer wall. | An analog to fundamental structural integrity measurements [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Kinesin Surface Clamp-Release Assay for Microtubule Stability

Purpose: To measure the shrinkage rates and stability of microtubules with different seam contents after release from a stabilizing rigor kinesin coat [6].

Materials:

- GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules (B-lattice or A-lattice enriched)

- Kinesin-1 motor proteins (non-processive, single-head constructs are suitable)

- Flow chamber with coverslip

- BRB80 or similar microtubule-stabilizing buffer

- ATP-containing buffer (e.g., BRB80 + 1mM ATP)

- TIRF or epifluorescence microscope

Method:

- Surface Preparation: Coat the flow chamber with a rigor kinesin solution (lacking ATP) to create a stable, non-motile kinesin layer.

- Microtubule Binding: Introduce fluorescently-labeled GMPCPP microtubules into the chamber. Allow them to bind to the kinesin-coated surface in ATP-free conditions. This "clamps" and stabilizes the MTs.

- Washing: Flush the chamber extensively with ATP-free buffer to remove any unbound microtubules and, critically, any residual Mal3 if A-lattice-enriched MTs were used [6].

- Release and Imaging: Rapidly flush the chamber with buffer containing 1mM ATP. This activates the kinesin motors, causing them to walk and releasing the microtubules from the stable clamp.

- Data Acquisition: Immediately acquire time-lapse images to track the lengths of the freed microtubules over time as they depolymerize.

Data Analysis:

- Measure microtubule length frame-by-frame.

- Plot length vs. time to calculate shrinkage rates (nm/s) for both plus and minus ends.

- Compare median shrinkage rates between B-lattice single-seam and A-lattice-enriched microtubules.

Protocol 2: Cryo-EM Seam Location and Reconstruction

Purpose: To accurately determine the αβ-tubulin register and seam location for each microtubule segment during single-particle cryo-EM processing [5].

Materials:

- Cryo-EM grid of microtubule sample (e.g., decorated with kinesin or EB)

- Processing software (e.g., FREALIGN, EMAN1/2, RELION)

- Access to a high-performance computing cluster

Method:

- Data Collection & Pre-processing: Collect movie-mode data on a direct electron detector. Perform drift and motion correction. Estimate the contrast transfer function (CTF) for each micrograph [5].

- Particle Picking: Manually or semi-automatically select microtubule segments from the micrographs. Extract these as overlapping boxes, with a non-overlapping region set to ~80 Ã… (the tubulin dimer repeat) [5].

- Initial Alignment & PF Number Determination: Compare raw particles to projections of low-pass-filtered reference models with different protofilament numbers (e.g., 12, 13, 14, 15 PFs). Use multi-reference alignment to determine the initial global orientation and correct PF number for each particle [5].

- Seam-Search Strategy: Refine alignment parameters using a local refinement algorithm. To determine the seam location, use specialized strategies such as:

- Projection Matching: Compare raw segments to projections of reference models with all possible seam locations and identify the one with the highest cross-correlation.

- Dimer Repeat Signal: Utilize the intrinsic power of the ~80 Ã… tubulin dimer repeat in the raw images to inform the seam search, which is particularly useful when marker protein signal is weak [5].

- 3D Reconstruction: Merge particles with the same PF number and refined seam location. Reconstruct the 3D density map using either pseudo-helical symmetry (applying symmetry operations but skipping the seam) or no symmetry (C1) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Explanation | Application in Seam Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mal3 (EB1 Homolog) | S. pombe end-binding protein. Used as a tool to nucleate microtubules with enriched A-lattice content when added at high concentrations [6]. | Generating defined A-lattice seam structures for stability assays. |

| GMPCPP Tubulin | Assembled from tubulin and a non-hydrolysable GTP analog. Forms microtubules that are structural analogues of the stabilizing GTP cap [6]. | Testing the intrinsic stability of different lattice architectures without complication from dynamic instability. |

| Rigor Kinesin | A kinesin motor mutant or state (e.g., lacking ATP) that binds tightly to microtubules without moving. | Stabilizing microtubules in surface assays for buffer exchange and controlled release [6]. |

| Direct Electron Detector | A camera for cryo-EM that allows for movie-mode data collection, enabling motion correction and high-resolution reconstruction [5]. | Essential for achieving the resolution needed to distinguish α/β-tubulin and identify seam location. |

| Iterative Helical Real Space Reconstruction (IHRSR) | A cryo-EM image processing algorithm modified for microtubules that iteratively refines helical parameters [5]. | Determining the 3D structure of microtubules, including those with a lattice seam. |

| A-770041 | A-770041, CAS:1140478-96-1, MF:C34H39N9O3, MW:621.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RGD peptide (GRGDNP) (TFA) | RGD peptide (GRGDNP) (TFA), MF:C25H39F3N10O12, MW:728.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Topological Defects as Hotspots for Tubulin Exchange and Lattice Remodeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are topological defects in the microtubule lattice, and why are they important? Topological defects are structural imperfections in the otherwise ordered microtubule lattice, such as sites where protofilament number changes or at seam dislocations [4]. These defects are crucial because they act as hotspots for biological activity, serving as preferred locations for tubulin dimer exchange and incorporation [4] [9]. They weaken the local lattice structure by disrupting tubulin-tubulin interactions, which in turn drives lattice dynamics, self-repair, and remodeling [4] [10].

2. How does the protein tau influence microtubule lattice dynamics? Contrary to its traditional role as a passive stabilizer, recent research shows that tau actively accelerates tubulin exchange within the microtubule lattice despite having no enzymatic activity [4] [11] [12]. Tau binds to the microtubule shaft and modulates lattice dynamics by stabilizing longitudinal tubulin-tubulin interactions while simultaneously destabilizing lateral ones. This increases lattice anisotropy and promotes the mobility and annihilation of topological defects, effectively facilitating lattice remodeling and self-repair [4].

3. My stabilized microtubules are fracturing during experiments. What could be causing this? Lattice fracture in end-stabilized microtubules is an intrinsic property of the GDP-lattice and occurs even in the absence of external forces or free tubulin [10]. Fracture typically initiates at pre-existing topological defects or monomer vacancies and propagates through the lattice [10]. The time to fracture is usually between 10 and 20 minutes, with the damaged region spanning about 1 µm along the microtubule axis before breaking [10]. Incorporating the protein tau has been shown to slow down the fracture process, as it promotes defect repair [4].

4. What is the relationship between GTP hydrolysis and lattice dynamics? The prevailing "interface-acting" (trans) model indicates that the nucleotide at the interface between tubulin dimers—not the nucleotide bound to an individual tubulin—controls the strength of tubulin-tubulin interactions [13]. GTP hydrolysis after incorporation into the lattice weakens these interactions, creating a strained GDP-lattice that is primed for dynamics. This strained state makes defect sites particularly susceptible to tubulin loss and exchange [14] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Tubulin Incorporation in Lattice Incorporation Assays

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: Variations in the density and distribution of inherent topological defects in your microtubule preparations can lead to inconsistent incorporation patterns [4] [10].

- Solution:

- Standardize Microtubule Seeds: Use GMPCPP-stabilized seeds to ensure a uniform nucleation template [4].

- Include a Regulator Protein: Incorporate a low concentration (e.g., 20 nM) of tau protein in your incorporation step. Tau homogenizes incorporation by preferentially targeting and enhancing exchange at defect sites [4].

- Control Incubation Time: Limit the incubation time with labelled tubulin (e.g., 15 minutes) to prevent saturation of incorporation sites, which can make quantification difficult [4].

Problem: Excessive Microtubule Fracture During Observation

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: The intrinsic instability of the GDP-tubulin lattice and the presence of multiple seam structures accelerate damage propagation [10].

- Solution:

- Reinforce the Lattice: Include tau protein (20 nM) in your imaging buffer. Tau slows down fracture by promoting defect repair, even in the absence of free tubulin [4].

- Minimize Photodamage: Ensure your imaging parameters (e.g., laser power, exposure time) are optimized to avoid exacerbating lattice damage.

- Quantify Fracture Kinetics: Use your experimental setup to measure the time to fracture. Compare your results to established baselines (typically 10-20 minutes) to diagnose if fracture is occurring faster than expected due to experimental conditions [10].

Table 1: Key Parameters from Microtubule Lattice Fracture Studies

| Parameter | Experimental Value | Context / Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Fracture | 10 - 20 minutes | For end-stabilized GDP-microtubules in the absence of free tubulin [10]. |

| Fracture Region Size | ~1 µm | Average length of the damaged lattice region before breakage [10]. |

| Lattice Anisotropy (A) | ~1.5 | Ratio of longitudinal to lateral binding energy ((A = \Delta G{\text{long}} / \Delta G{\text{lat}})) derived from fracture simulations [10]. |

Table 2: Effect of Tau on Lattice Incorporation Metrics

| Metric | Condition (15 min incubation) | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median Incorporation Length | 0 nM Tau | 0.7 µm [4] |

| 20 nM Tau | 1.2 µm [4] | |

| Median Distance Between Incorporations | 0 nM Tau | 12.4 µm [4] |

| 20 nM Tau | 6.6 µm [4] | |

| Tubulin Loss from Original Lattice | 0 nM & 20 nM Tau | 7% - 15% reduction in fluorescence intensity [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Studying Tau-Stimulated Tubulin Incorporation at Defect Sites

This protocol details how to visualize and quantify how tau promotes tubulin exchange at topological defects in the microtubule lattice [4].

Workflow Diagram: Tau-Stimulated Tubulin Incorporation Assay

Materials:

- Microtubule Seeds: GMPCPP-stabilized, surface-attached [4].

- Tubulin: Green-labeled GTP-tubulin (for initial growth), red-labeled GTP-tubulin (for incorporation assay), and unlabeled GMPCPP-tubulin (for capping) [4].

- Regulator Protein: Human 2N4R tau [4].

- Imaging Buffer: Tubulin-free buffer for final imaging [4].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Grow Microtubules: Dynamically grow microtubules from the surface-attached seeds using green-labelled GTP-tubulin [4].

- Cap Microtubule Tips: Inhibit further tip dynamics by capping the microtubules with slowly hydrolysable GMPCPP-tubulin. This isolates lattice dynamics from tip dynamics [4].

- Incorporation Step: Incubate the capped microtubules with a solution containing red-labelled GTP-tubulin (e.g., 8 µM) and your chosen concentration of tau (e.g., 0 nM for control, 0.5 nM, or 20 nM) for a defined period (e.g., 15 or 30 minutes) [4].

- Wash and Image: Wash out free tubulin to reduce background fluorescence. Image the microtubules to visualize the stretches of incorporated red tubulin. To correlate incorporation sites with weakness, continue imaging in tubulin-free buffer until microtubule fracture occurs [4].

Key Observations:

- In the presence of 20 nM tau, you should observe longer and more frequent stretches of incorporated tubulin [4].

- Approximately 40% of fracture events will occur at these incorporation stretches, identifying them as pre-existing defect sites [4].

- A slight decrease (7-15%) in the original (green) lattice fluorescence at incorporation sites indicates exchange (replacement) rather than simple addition of tubulin [4].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Lattice Anisotropy from Fracture Kinetics

This protocol uses a kinetic Monte Carlo model to deduce fundamental lattice energy parameters by simulating microtubule fracture [10].

Workflow Diagram: Lattice Anisotropy Simulation

Model Setup:

- Lattice Representation: Model the microtubule as a 2D lattice at the monomer scale, representing a 13-protofilament B-lattice with a possible A-lattice seam [10].

- Energy Parameters: Define the binding energies for longitudinal ((\Delta G{\text{long}})) and lateral ((\Delta G{\text{lat}})) interactions. The total binding energy for a fully surrounded dimer is (\Delta G{\text{b}} = 2\Delta G{\text{long}} + 2\Delta G_{\text{lat}}) [10].

- Anisotropy Definition: The key parameter, lattice anisotropy, is defined as (A = \Delta G{\text{long}} / \Delta G{\text{lat}}) [10].

- Detachment Kinetics: The detachment rate (k{mn}) of a dimer with (m) longitudinal and (n) lateral neighbors is given by: (k{mn} = \frac{1}{\tau} e^{\beta(m\Delta G{\text{long}} + \frac{n}{2}\Delta G{\text{lat}} - \frac{\Delta G_{\text{b}}}{2})}) where (\tau) is the off-rate for a corner dimer, and (\beta = 1/kT) [10].

Simulation and Analysis:

- Introduce Defect: Start with a 10 µm long, end-stabilized microtubule and introduce an initial monomer vacancy at a specific lattice position [10].

- Run Simulation: Simulate the progression of tubulin loss from this initial defect. The damage will typically propagate longitudinally faster than laterally if (A > 1) [10].

- Compare to Experiment: Adjust the anisotropy parameter (A) in your model so that the simulated time to fracture and damage propagation pattern match experimental observations (e.g., fracture in 10-20 minutes). Recent studies suggest (A) is bounded at approximately 1.5, indicating a less anisotropic lattice than previously thought [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Microtubule Lattice Dynamics

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Details / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GMPCPP-tubulin | A slowly hydrolysable GTP analogue. Used to create stable microtubule "seeds" for nucleation and to "cap" microtubule ends, allowing the study of pure lattice dynamics isolated from tip dynamics [4]. | Non-hydrolysable nucleotide analogue [4]. |

| Human 2N4R Tau | A specific isoform of the microtubule-associated protein tau. Used to investigate how MAPs modulate lattice dynamics, particularly in accelerating tubulin exchange and remodeling defects [4]. | Binds laterally along the microtubule lattice [4]. |

| Kinetic Monte Carlo Model | A computational model used to simulate the stochastic process of tubulin loss and incorporation. Essential for deducing energy parameters (like anisotropy) from experimental data on lattice fracture and exchange [10]. | Represents the MT as a 2D lattice; uses Arrhenius kinetics for detachment rates [10]. |

| End-Stabilized Microtubule Construct | A microtubule whose dynamic ends are chemically or structurally blocked. This is the fundamental experimental setup for studying intrinsic lattice dynamics without the confounding effects of tip growth or shrinkage [4] [10]. | Created by capping with GMPCPP-tubulin [4]. |

| Interference Reflection Microscopy | An imaging technique that allows visualization of microtubules without fluorescent labels. Used to control for potential artifacts introduced by fluorescent tags in lattice dynamics experiments [4]. | Validates findings from fluorescence microscopy [4]. |

| Teicoplanin A2-4 | Teicoplanin A2-4, MF:C89H99Cl2N9O33, MW:1893.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FT-1518 | FT-1518, MF:C20H26N8O, MW:394.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the cis-acting (self-acting) and trans-acting (interface-acting) models of nucleotide function in microtubules?

The fundamental difference lies in which nucleotide controls the strength of the tubulin:tubulin interaction.

- Cis-acting (Self-acting) Model: The nucleotide (GTP or GDP) bound to a specific tubulin dimer dictates how strongly that same dimer interacts with the microtubule lattice. It was historically thought that GTP induces a straight conformation for strong binding, while GDP induces a curved conformation for weak binding [15] [13].

- Trans-acting (Interface-acting) Model: The nucleotide at the interface between two tubulin dimers controls the binding strength. The nucleotide bound to the lower dimer in the lattice influences how tightly the upper dimer above it binds [16] [15]. This model is supported by structural data showing that both GTP- and GDP-tubulin adopt a curved conformation when unpolymerized [15] [13].

Q2: How does the nucleotide state (GDP vs. GTP) ultimately lead to microtubule catastrophe?

Catastrophe is initiated by the loss of the protective "GTP cap." Within the microtubule lattice, GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP. GDP-bound tubulin forms a labile lattice with weaker lateral contacts. When the GTP cap is lost and GDP-tubulin becomes exposed at the microtubule end, the weakened interactions can no longer sustain growth, prompting a rapid transition to shrinkage [16].

Q3: Why does GDP-tubulin "poison" microtubule growth when added to the solution, and which end is more affected?

GDP-tubulin has a lower affinity for the microtubule end than GTP-tubulin. When GDP-tubulin is incorporated into a growing end, it creates a weak point that destabilizes the structure. This "poisoning" effect is disproportionately stronger at the plus-end than at the minus-end. This end-specificity provides key experimental evidence for the interface-acting (trans) mechanism, as the plus-end has a distinct nucleotide configuration that is more susceptible to disruption by GDP [15] [13].

Q4: What is the role of nucleotide exchange in microtubule dynamics?

GDP-to-GTP exchange on terminal GDP-bound tubulin subunits at the microtubule end can mitigate the catastrophe-promoting effects of GDP exposure. By allowing a "weak" GDP-bound terminal subunit to be converted back to a "strong" GTP-bound state, nucleotide exchange helps maintain the integrity of the GTP cap and reduces the frequency of catastrophe [16] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Catastrophe Frequency In Vitro

Problem: Your reconstituted microtubules undergo catastrophe too frequently, making it difficult to observe sustained growth or gather reliable dynamic instability parameters.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Low effective concentration of active GTP-tubulin.

- Solution: Increase the total tubulin concentration. Confirm the ratio of GTP to tubulin is sufficient (typically a molar excess of GTP) and prepare fresh tubulin in GTP-containing buffer just before the experiment.

- Cause: Excessive incorporation of GDP-tubulin.

- Solution: Ensure your tubulin preparation is of high quality and free of contaminating GDP. Use a rapid purification protocol or purchase commercial high-purity tubulin. Experimentally, using a slowly-hydrolyzable GTP analog (e.g., GMPCPP) can suppress catastrophe entirely for diagnostic purposes [15] [13].

- Cause: Unfavorable buffer conditions.

- Solution: Optimize buffer composition, specifically Mg²⺠concentration, pH, and the presence of glycerol or other stabilizing agents.

Issue 2: No Observable Differential Effect of GDP on Plus vs. Minus Ends

Problem: When performing mixed-nucleotide assays with GDP-tubulin, you do not observe the predicted disproportionate slowing of plus-end growth compared to the minus-end.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate suppression of GTP hydrolysis and catastrophe.

- Cause: Difficulty in reliably distinguishing and tracking the two ends.

- Solution: Use fiduciary markers (e.g., GMPCPP seeds) with distinct geometries to unambiguously identify plus and minus ends during data analysis.

Table 1: Key Parameters from Computational Models of Microtubule Dynamics

| Parameter | Cis-acting (Self-acting) Model | Trans-acting (Interface-acting) Model | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GTPase Rate Requirement | Faster GTPase rate to achieve benchmark catastrophe frequency [16] | Slower GTPase rate to achieve the same catastrophe frequency [16] | The trans-acting model requires slower hydrolysis to explain observed dynamics. |

| GDP Effect on Plus-End | Moderate, proportional decrease in growth rate [15] [13] | Strong, disproportionate decrease in growth rate ("poisoning") [15] [13] | A key testable difference between the models. |

| GDP Effect on Minus-End | Proportional decrease in growth rate [15] [13] | Proportional decrease in growth rate (identical to cis-model) [15] [13] | The effect is identical for both models at the minus-end. |

| Impact of Nucleotide Exchange | Not a primary feature in early models | Reduces catastrophe frequency by mitigating GDP-poisoning [16] [15] | Incorporated into newer models to match experimental data. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| GMPCPP (slowly-hydrolyzable GTP analog) | Generates stable, non-dynamic microtubule seeds; used in mixed-nucleotide assays to suppress catastrophe and isolate the effects of GDP on pure elongation [15] [13]. |

| Mutant αβ-tubulin (with altered nucleotide affinity) | Used to selectively perturb the rate of GDP-to-GTP exchange on the microtubule end, testing the hypothesis that exchange influences catastrophe frequency [16]. |

| GDP-tubulin | Used in "mixed-nucleotide" assays to directly test the poisoning effect of incorporated GDP subunits on microtubule growth and to discriminate between cis and trans mechanisms [15] [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mixed Nucleotide Assay to Distinguish Nucleotide Action Mechanisms

Objective: To experimentally determine whether nucleotide action follows a self-acting or interface-acting mechanism by measuring the differential effect of GDP-tubulin on plus-end vs. minus-end growth rates.

Background: This protocol tests a key prediction: interface-acting mechanisms cause GDP-tubulin to disproportionately inhibit plus-end growth compared to minus-end growth, while self-acting mechanisms inhibit both ends equally [15] [13].

Materials:

- Purified tubulin

- GMPCPP

- GDP

- GTP

- BRB80 buffer (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8)

- Flow chamber slides

- TIRF or fluorescence microscope

Method:

- Stabilized Seed Preparation: Polymerize tubulin in the presence of GMPCPP to form stabilized microtubule seeds. These seeds are then immobilized on a coverslip via a biotin-neutravidin bridge in a flow chamber.

- Prepare Elongation Mix: Create an elongation buffer containing a low concentration of tubulin, a sustaining concentration of GTP, and a defined fraction of GDP-tubulin (e.g., 0-20%). A key element is including a sufficient concentration of GMPCPP in the mix to suppress catastrophe during the observation window.

- Image Acquisition: Flow the elongation mix into the chamber and immediately begin time-lapse imaging using fluorescence microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Track the growth of both plus and minus ends from the GMPCPP seed over time. Calculate the elongation rates for each end across the different GDP-tubulin conditions.

Expected Outcome: Data supporting the interface-acting model will show a steep, non-linear decrease in the plus-end growth rate as the percentage of GDP-tubulin increases, while the minus-end growth rate will decrease in a more linear, proportional manner.

Protocol 2: Measuring Catastrophe Frequency with Nucleotide Exchange Perturbations

Objective: To test the hypothesis that GDP-to-GTP exchange on terminal microtubule subunits influences catastrophe frequency.

Background: Simulations suggest that allowing GDP-to-GTP exchange on terminal subunits mitigates catastrophe [16]. This can be tested experimentally using reagents that alter nucleotide binding affinity.

Materials:

- Wild-type tubulin

- Mutant tubulin with weakened nucleotide binding affinity [16]

- GTP

- BRB80 buffer

- Flow chamber setup

- TIRF microscope

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare two separate reactions: one with wild-type tubulin and another with mutant tubulin that has a higher rate of nucleotide exchange.

- Dynamic Assay: Immobilize GMPCPP seeds in a flow chamber and initiate growth by flowing in each tubulin preparation in GTP-containing buffer.

- Data Collection: Record movies of microtubule dynamics. For each growing microtubule, measure the time from the start of growth until the moment of catastrophe.

- Quantification: Plot the survival fraction (microtubules that have not yet undergone catastrophe) over time. The catastrophe frequency is inversely related to the time at which 50% of the microtubules have undergone catastrophe.

Expected Outcome: The mutant tubulin with higher nucleotide exchange rates is predicted to exhibit a lower catastrophe frequency compared to wild-type tubulin, supporting a protective role for nucleotide exchange at the microtubule end.

Mechanism and Workflow Visualizations

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Microtubule Breakage During Motility Assays

Reported Issue: Microtubules frequently break or completely depolymerize during gliding or motility assays.

Underlying Cause: The mechanical work produced by walking molecular motors can break tubulin dimer interactions, leading to lattice damage and breakage [17]. This is particularly pronounced in GDP-lattice regions, which are less stable than GTP- or taxol-stabilized lattices [17].

Solutions:

- Stabilize the Lattice: Use microtubules stabilized with taxol or assembled with GMPCPP, a non-hydrolysable GTP analogue, to prevent motor-induced destruction [17].

- Modify Buffer Conditions: Include 10% glycerol in your reaction mixture to intrinsically increase microtubule stability [17].

- Reduce Photo-Toxicity: Use Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM) to visualize microtubules without the need for fluorescent labels, which can cause photo-damage [17].

- Confirm ATP Dependence: Verify that breakage is ATP-dependent. A lack of breakage in the presence of non-hydrolysable AMPPNP confirms a motor-based mechanism rather than spontaneous lattice disintegration [17].

Guide: Resolving Lattice Heterogeneity in Structural Analysis

Reported Issue: Standard single-particle analysis (SPA) or subtomogram averaging (STA) reveals a seemingly homogenous microtubule lattice, failing to capture structural variations like multiple seams or holes.

Underlying Cause: Conventional averaging techniques combine thousands of images to produce a single representative structure, which masks the intrinsic structural heterogeneity of individual microtubules [18].

Solutions:

- Implement Segmented Averaging: Use a Segmented Subtomogram Averaging (SSTA) strategy. This involves dividing a full-length microtubule model into shorter segments and calculating subtomogram averages for each segment to reveal local variations in seam number and location [18].

- Use Lattice Decorations: Decorate microtubules with kinesin motor-domains, which bind every αβ-tubulin heterodimer. This provides a high-density marker to determine the underlying organization of tubulin dimers [18].

- Model Protofilament Paths: Carefully model individual protofilament paths and microtubule centers in software like IMOD/3dmod to use as a template for sub-volume extraction and analysis in programs like PEET [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the difference between the A-type and B-type microtubule lattice?

The microtubule lattice is composed of αβ-tubulin heterodymers. The difference lies in their lateral interactions:

- A-type lattice (Heterotypic): Characterized by lateral interactions between α- and β-tubulin monomers (α-β, β-α). This type of interaction is predominantly found at the "seam" of the microtubule [18].

- B-type lattice (Homotypic): Characterized by lateral interactions between like monomers (α-α, β-β). This is the predominant lattice type in microtubules assembled in vitro [18].

FAQ 2: What evidence is there for microtubule self-repair in living cells?

Studies have shown that the microtubule lattice is dynamic and not static. The damage induced by molecular motors walking on the lattice—which can remove tubulin dimers—can be compensated for by the insertion of free tubulin dimers from the cytoplasm back into the lattice shaft. This coupling between motor-based damage and tubulin incorporation is a key self-repair mechanism that allows microtubules to survive mechanical stress [17].

FAQ 3: Why is lattice heterogeneity, such as the presence of multiple seams, significant?

The textbook view of a single seam in a microtubule is an oversimplification. Multi-seams are frequent in microtubules assembled in vitro [18]. Furthermore, the location and number of seams can vary within a single microtubule [18]. These seams can act as pre-existing pathways that accelerate damage propagation and fracture [10]. This heterogeneity has profound consequences for understanding microtubule dynamics, as it suggests tubulin can engage in unique lateral interactions and provides a molecular basis for tubulin exchange not just at the ends, but also in the shaft [18].

FAQ 4: What are the key energetic parameters that govern lattice stability and fracture?

The stability of the GDP-microtubule lattice is governed by the binding energies between tubulin dimers. The total binding energy for a fully surrounded dimer is described as ΔGb = 2ΔGlong + 2ΔGlat [10]. A critical parameter is the lattice anisotropy (A), defined as the ratio of longitudinal to lateral binding energies (A = ΔGlong / ΔG_lat) [10]. Recent research comparing simulations with fracture experiments suggests this intrinsic ratio is bounded at approximately 1.5, indicating a weaker anisotropy than previously predicted from tip-growth models [10].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research on microtubule lattice dynamics.

Table 1: Microtubule Lifetime Under Motor-Induced Stress

| Motor Type | Motor Concentration | Average Microtubule Lifetime (min) | Conditions & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No motor) | - | 20.0 ± 2.0 | RICM, 10% Glycerol [17] |

| Klp2 (Kinesin-14) | 1 nM | 8.7 ± 0.2 | RICM, 10% Glycerol [17] |

| Klp2 (Kinesin-14) | 10 pM | ~20.0 (No significant effect) | RICM, 10% Glycerol [17] |

| Cytoplasmic Dynein | 1 nM | 12.4 (Reduced from 20) | RICM [17] |

| Control (Spontaneous) | - | 12.3 ± 0.1 | Fluorescence microscopy [17] |

| Klp2 (Kinesin-14) | 1 nM | 5.3 ± 0.1 | Fluorescence microscopy [17] |

Table 2: Lattice Fracture Parameters from Kinetic Modeling

| Parameter | Symbol | Value / Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice Anisotropy | A = ΔGlong / ΔGlat | ~1.5 (bounded) | Challenges previous predictions; indicates weaker anisotropy [10] |

| Time to Fracture | - | 10 - 20 minutes | For end-stabilized MTs in absence of free tubulin [10] |

| Damage Zone Size | - | ~1 μm | Average length of damaged lattice region before fracture [10] |

| Breaking Event Frequency (Klp2) | - | 1 event / 14 μm | At high motor concentration (10 nM) [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Segmented Subtomogram Averaging (SSTA) for Lattice Analysis

This protocol is used to characterize the structural heterogeneity of individual microtubule lattices, such as the presence and variation of multiple seams [18].

Key Software: IMOD (v4.12.30 or later) and PEET (v1.16.0 alpha or later) [18].

Procedure:

Data and Directory Preparation:

- Obtain a cryo-electron tomogram of your microtubule sample (e.g., from a public repository like EMPIAR).

- Create a working directory and save the tomogram file (e.g.,

your_tomogram.mrc).

Modeling Protofilament Paths with 3dmod:

- Open the tomogram in 3dmod using the command:

3dmod your_tomogram.mrc MT_Model.mod. - In the 3dmod Information Window, select Model mode.

- Use the Image > Slicer function to view the microtubule in cross-section. Adjust the X and Z rotation sliders (e.g., 90.0 and -57.4) to clearly visualize and individualize protofilaments.

- With the Open object type selected and a sphere radius of 3, manually trace the path of a reference protofilament by placing points. It is advised to model consistently from the bottom to the top of the tomogram.

- Regularly save your model during this process.

- Open the tomogram in 3dmod using the command:

Generating the Full Microtubule Model:

- The initial protofilament model serves as a template. Use PEET commands to generate models for all other protofilaments and the microtubule center, creating a full template for the microtubule.

Subtomogram Averaging and Segmentation:

- Extract sub-volumes at every kinesin motor domain position (used for decoration) to compute a full, global subtomogram average of the microtubule.

- Divide this full model into shorter segments (e.g., 100-500 nm in length).

- Using the global average parameters as an initial template, compute a separate subtomogram average for each individual segment.

Analysis of Heterogeneity:

- Analyze the segmented averages to identify local variations, such as changes in the number and position of seams (A-lattice) within the predominantly B-lattice structure.

Detailed Protocol: Assessing Motor-Induced Microtubule Destruction

This protocol describes a "motility assay" to study how walking molecular motors damage and break the microtubule lattice [17].

Key Materials:

- Capped GDP-microtubules (GDP-lattice with GMPCPP-stabilized ends).

- Purified motor proteins (e.g., kinesin-1, kinesin-14/Klp2, or cytoplasmic dynein).

- Flow cells with non-adhesive surface coatings or micropatterned attachments.

Procedure:

Microtubule Preparation:

- Prepare capped GDP-microtubules. This involves growing a GDP-tubulin lattice from a stable seed, but protecting it from spontaneous depolymerization by capping both ends with a short section of GMPCPP-tubulin.

Assay Geometry:

- In a gliding assay, motors are attached to a glass surface, and microtubules glide over them.

- In a motility assay, attach the capped microtubules to the coverslip surface (e.g., via patterned seeds), leaving the majority of the shaft unattached. The motors then walk along these surface-attached microtubules.

Data Acquisition with Reduced Photo-Damage:

- To minimize fluorescence-induced damage, use Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM) to visualize label-free microtubules and non-fluorescent motors [17].

- Alternatively, include 10% glycerol in the reaction buffer to increase intrinsic microtubule stability.

Quantification of Breakage:

- Record time-lapse videos of the microtubules after introducing motors and ATP.

- Quantify microtubule lifetime and the frequency of breakage events along the shaft (distinct from the loss of the protective cap).

- Compare these metrics to control experiments performed without motors or without ATP (using AMPPNP).

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Microtubule Lattice Dynamics Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Details & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| GMPCPP Tubulin | Stabilizing GTP analogue | Used to create stable microtubule "caps" or seeds that protect GDP-lattices from end-wise depolymerization; mimics GTP-bound state [17]. |

| Taxol | Microtubule-stabilizing drug | Prevents depolymerization of the entire microtubule in gliding assays, allowing isolation of motor effects on the shaft [17]. |

| Kinesin Motor-Domains | Lattice decoration for structural studies | Binds every αβ-tubulin heterodimer, providing a high-density marker to resolve underlying tubulin organization in techniques like SSTA [18]. |

| Klp2 (Kinesin-14) | Minus-end-directed motor for damage assays | A non-processive motor used in motility assays to study force-induced breakage along the microtubule shaft [17]. |

| Cytoplasmic Dynein | Minus-end-directed motor for damage assays | A processive motor; single dimers can be used at low concentrations (e.g., 50 pM) to induce lattice breakage [17]. |

| AMPPNP | Non-hydrolysable ATP analogue | Locks motors in a bound, non-moving state; used as a negative control to confirm breakage requires motor movement [17]. |

| IMOD/PEET Software | Structural analysis and averaging | Software suite for tomographic reconstruction, modeling, and subtomogram averaging, essential for SSTA [18]. |

| Jak-IN-5 | Jak-IN-5|JAK Inhibitor|C27H31FN6O | |

| TDP1 Inhibitor-1 | TDP1 Inhibitor-1, MF:C26H26N2O5, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Tools for Lattice Analysis: From Atomic Resolution to Cellular Context

Segmented Subtomogram Averaging (SSTA) for Resolving Lattice Heterogeneity

Purpose and Applications of SSTA

Segmented Subtomogram Averaging (SSTA) is an advanced cryo-electron tomography technique specifically designed to investigate the structural heterogeneity within individual microtubules. Traditional Single-Particle Analysis (SPA) and full-length Subtomogram Averaging (STA) approaches generate averaged structures assumed to represent the entire sample, potentially masking intrinsic variations. In contrast, SSTA addresses this limitation by dividing microtubules into shorter segments for individual analysis, revealing dynamic changes in lattice organization that occur along the shaft of single microtubules [19] [20].

The primary application of SSTA in microtubule research is the detailed characterization of lattice heterogeneity, including:

- Mapping A- and B-lattice seams: Identifying regions where αβ-tubulin heterodimers engage in heterotypic (α-β, β-α) versus homotypic (α-α, β-β) lateral interactions [20]

- Detecting multi-seam configurations: Revealing the presence of multiple seam regions within individual microtubules, contrary to the traditional "textbook" single-seam model [19]

- Identifying lattice discontinuities: Uncovering holes of one to a few tubulin subunits within the microtubule wall that form at transition zones where seam number or location changes [21]

- Comparing assembly conditions: Analyzing structural differences between microtubules assembled from purified tubulin versus those formed in cytoplasmic extracts [21]

This technique has demonstrated that changes in seam number and location are intrinsic properties of microtubules assembled from purified tubulin, and that these transitions occur with varying frequency along individual microtubules [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SSTA Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor kinesin decoration | Incorrect motor-domain concentration; Non-optimal buffer conditions | Titrate kinesin concentration (typically 1-5 µM); Verify binding conditions using negative stain EM | Always include control microtubules with known decoration pattern; Confirm activity of kinesin stock |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio in tomograms | Insufficient tilts; Radiation damage; Ice contamination | Implement dual-axis tilt series acquisition [21]; Use modern direct electron detectors; Optimize cryo-grid preparation | Use fiduciary gold markers for alignment; Collect data at higher magnification (≥×50,000) for critical regions |

| Incomplete microtubule modeling | Microtubule curvature; High background noise | Model from bottom to top of tomogram; Adjust X-rotation to maximize protofilament contrast [20] | Ensure microtubules are parallel to tomogram plane in thick ice; Use Slicer Window in IMOD for 3D orientation |

| Aberrant protofilaments in averages | Genuine lattice transitions; Registration errors | Apply Segmented SSTA to identify transition zones [21]; Verify with Fourier space filtering | Increase segment length to 125-180 nm for better statistics; Cross-check with raw tomogram data |

Computational and Software Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting SSTA Computational Workflow

| Issue | Symptoms | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| PEET/IMOD installation failures | Software won't launch; Missing dependencies | Verify system requirements: macOS, Windows, or Linux with ≥16 GB RAM, 4 physical cores [20]; Check PATH environment variables |

| Model registration failures | Points not aligning to kinesin densities; Poor averages | Adjust sphere radius to 3 in 3dmod Object Type settings [20]; Re-check microtubule center modeling |

| Segment alignment discrepancies | Inconsistent seam counts between segments | Use main parameters of full-length microtubule as template for segments [19]; Verify motive list division |

| Reconstruction artifacts | Streaking; Missing wedges | Implement wedge-masked difference maps [19]; Consider iterative refinement cycles |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key advantage of SSTA over conventional STA for microtubule analysis? A1: While conventional STA generates a single average structure representing the entire microtubule, SSTA divides microtubules into shorter segments (typically 125-180 nm) to analyze structural variations along individual microtubules. This enables detection of changes in seam number and location, as well as identification of lattice discontinuities that would be averaged out in full-length approaches [19] [21].

Q2: Why is kinesin motor-domain decoration essential for SSTA of microtubules? A2: Kinesin motor-domains bind specifically to every β-tubulin subunit within the microtubule lattice, serving as unambiguous markers for determining the underlying organization of αβ-tubulin heterodimers. This binding pattern allows researchers to distinguish between A-lattice (heterotypic) and B-lattice (homotypic) interactions and accurately map seam locations [20] [21].

Q3: How frequently do lattice transitions occur in microtubules? A3: Transition frequency varies significantly between microtubules and assembly conditions. Analysis of microtubules assembled from purified porcine brain tubulin with GTP revealed an average transition frequency of 3.69 µmâ»Â¹, but with high heterogeneity—some microtubules showed no transitions while others reached frequencies up to ~15 µmâ»Â¹ [21].

Q4: Can SSTA be applied to microtubules in intact cells? A4: Currently, application to intact cells is challenging as it requires membrane removal with detergents to allow kinesin access to microtubules. While this has been demonstrated for cytoplasmic microtubules [20], new strategies are needed for studying native microtubule lattices in unperturbed cellular environments.

Q5: What are the minimum computational requirements for SSTA processing? A5: The protocol can be run on computers with at least one CPU with four physical cores and 16 GB of RAM. The software (IMOD and PEET) is multi-platform and compatible with macOS, Windows, and Linux operating systems [20].

Q6: How does buffer condition affect microtubule lattice heterogeneity? A6: The nucleotide conditions (GTP vs. GMPCPP) significantly influence lattice regularity. Microtubules assembled with GMPCPP, a slowly hydrolysable GTP analogue, generally show more regular organization and enable better resolution tomograms due to the ability to use lower tubulin concentrations (10 µM vs. 40 µM for GTP) [21].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Data Collection

Microtubule Assembly and Kinesin Decoration:

- Polymerization conditions: Assemble microtubules from purified porcine brain tubulin (10-40 µM) in BRB80 buffer (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8) with 1 mM GTP or GMPCPP [21]

- Kinesin decoration: At polymerization plateau, add kinesin motor-domains (final concentration 1-5 µM) and incubate for 5-10 minutes before grid preparation

- Vitrification: Apply 3-5 µL sample to freshly glow-discharged cryo-EM grids, blot, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane

Cryo-Electron Tomography Data Collection:

- Tilt series acquisition: Collect dual-axis tilt series typically from ±60° with 1-2° increments at 25,000-50,000× magnification [21]

- Defocus range: Use -4 to -8 µm defocus depending on ice thickness and desired resolution

- Dose management: Implement dose-fractionation with total dose of 80-120 eâ»/Ų distributed across the tilt series

SSTA Computational Workflow

Detailed SSTA Processing Steps:

Tomogram Preprocessing (IMOD):

tiltalign: Align tilt series using gold fiducialstomoproc: Apply preprocessing filters and correctionsetomo: Reconstruct tomograms with weighted back-projection or SIRT

Microtubule Modeling (3dmod):

- Open tomogram:

3dmod GMPCPP_tomoFig5_bin4.mrc MT_Model.mod - Use Slicer Window (Image > Slicer) to visualize microtubule cross-sections

- Set Object type to "Open" with Sphere radius for points = 3 [20]

- Model protofilament path by placing points along filament center

- Open tomogram:

Subtomogram Extraction and Averaging (PEET):

- Extract sub-volumes (~50 nm³) at each kinesin motor domain position

- Generate initial averages using full microtubule length

- Divide model into segments of 125-180 nm length

- Process segmented sub-volumes using full-length parameters as template

Heterogeneity Analysis:

- Compare kinesin binding patterns between segments

- Identify lattice transitions by tracking protofilament registration

- Map seam location and count variations along microtubule length

- Detect holes by identifying out-of-phase kinesin periodicity

Table 3: Microtubule Lattice Transition Frequencies Under Different Assembly Conditions

| Assembly Condition | Average Transition Frequency (µmâ»Â¹) | Microtubules Analyzed | Total Segments | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified tubulin + GTP | 3.69 | 24 | 195 | High heterogeneity: 0 to ~15 µmâ»Â¹ transition frequency [21] |

| Purified tubulin + GMPCPP | Reduced (data not quantified) | Multiple | Not specified | More regular organization; clearer hole visualization [21] |

| Xenopus egg cytoplasmic extracts | Lower than in vitro | Multiple | Not specified | Cellular components regulate lattice regularity [21] |

Table 4: Computational Resources and Software Specifications

| Component | Minimum Requirements | Recommended Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Computer Hardware | 4 physical cores, 16 GB RAM | Apple M1 Max 3.22 GHz, 64 GB RAM, 4 TB SSD [20] |

| Software Versions | IMOD 4.12.30, PEET 1.16.0 alpha | Latest stable releases with bug fixes |

| Peripheral Equipment | Standard three-button mouse | Extended keyboard with numeric keypad [20] |

| Storage | 500 GB free space | 4 TB SSD for large datasets |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for SSTA Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Specifications | Function in SSTA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Porcine brain tubulin | Purified (>95% purity), 10-40 µM working concentration | Microtubule polymerization substrate for in vitro assembly [21] |

| Kinesin motor-domains | Recombinantly expressed, purified, 1-5 µM decorating concentration | Binds every αβ-tubulin heterodimer to mark lattice organization [19] [20] |

| GMPCPP | Slowly hydrolysable GTP analogue, 1 mM in assembly buffer | Produces more stable, regular microtubules for high-resolution analysis [21] |

| Cryo-EM grids | Quantifoil or C-flat, freshly glow-discharged | Sample support for vitrification and tomography data collection |

| Xenopus egg cytoplasmic extracts | Freshly prepared, competence-verified | Physiological microtubule assembly environment comparison [21] |

Kinetic Monte Carlo Simulations for Modeling Lattice Dynamics and Fracture

Frequently Asked Questions: Kinetic Monte Carlo Method

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) simulations? KMC is a stochastic simulation technique designed to model the time evolution of systems dominated by rare events. Unlike molecular dynamics, which simulates every vibration, KMC jumps from state to state, with the probability of each transition governed by its rate constant. This makes it particularly suited for simulating processes like microtubule lattice dynamics and fracture, which occur on timescales far beyond those accessible by atomistic simulation [22] [23].

Q2: In the context of microtubule fracture, what constitutes an "event" in a KMC simulation? An "event" is the discrete detachment of a tubulin dimer from the lattice. The rate of detachment ((k{mn})) for a specific dimer depends on the number of its intact longitudinal ((m)) and lateral ((n)) monomer contacts, following the Arrhenius-type equation [10]: [ k{mn} = \frac{1}{\tau}e^{\beta\left(m\Delta G{\text{long}} + {n\over 2}\Delta G{\text{lat}} - {\Delta G{\text{b}}\over 2}\right)} ] Here, (1/\tau) is the off-rate constant for a corner dimer, (\beta) is the inverse thermodynamic temperature, and (\Delta G{\text{long}}) and (\Delta G_{\text{lat}}) are the longitudinal and lateral binding energies, respectively [10].

Q3: Our KMC simulation of microtubule fracture is running too slowly. What could be the cause?

KMC simulations can be slowed down by a "timescale disparity problem," where one type of event (e.g., dimer detachment) is extremely rare compared to others. Furthermore, in a lattice model, the algorithm must check the status of every dimer and its neighbors at every step. For a large 10µm microtubule containing hundreds of thousands of dimers, this computational overhead is significant. Implementing advanced KMC algorithms, like the (n)-fold way or using performance-optimized libraries such as kmos, can help overcome this [22] [23].

Q4: Why does a monomer vacancy in the microtubule lattice lead to asymmetric fracture propagation? A monomer vacancy creates a local defect. When the simulation starts from a monomer vacancy within the B-lattice, two new seams emanate from the defect. As the vacancy grows, the longitudinal fracture front that propagates across these seams gains "seam dimers" with different neighbor counts, accelerating its detachment rate compared to the front propagating into the perfect B-lattice. This breaks the symmetry and leads to faster propagation in one direction [10].

Q5: How is lattice anisotropy defined and what is its significance in microtubule fracture models? Lattice anisotropy ((A)) is defined as the ratio of longitudinal to lateral binding energies [10]: [ A = \frac{\Delta G{\text{long}}}{\Delta G{\text{lat}}} ] This parameter critically influences the shape and speed of damage propagation. Recent KMC studies matching experimental fracture data suggest the intrinsic anisotropy is bounded at approximately 1.5, which is lower than previous estimates from tip-growth models. This weaker anisotropy results in more balanced longitudinal and lateral crack growth [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulation Does Not Reproduce Experimental Fracture Times

Problem The simulated time for a microtubule to fracture is significantly shorter or longer than the experimentally observed 10-20 minutes [10].

Investigation & Resolution

| Investigation Step | Action & Parameters to Check |

|---|---|

| Verify Lattice Energy Parameters | Confirm the values for (\Delta G{\text{long}}) and (\Delta G{\text{lat}}) in your input file. The total binding energy for a fully surrounded dimer is (\Delta Gb = 2\Delta G{\text{long}} + 2\Delta G_{\text{lat}}), and it must be strongly negative ((\ll kT)) to ensure a stable lattice [10]. |

| Check the Anisotropy Ratio | Ensure the anisotropy (A = \Delta G{\text{long}} / \Delta G{\text{lat}}) is set appropriately. For GDP microtubules, a value around 1.5 is consistent with recent fracture data [10]. |

| Inspect Initial Defect Setup | Validate the initial condition. The simulation should start from a defined defect (e.g., a monomer vacancy) rather than a perfect lattice, as spontaneous dimer loss from a full lattice is a rare event [10]. |

Issue 2: Unphysical Fracture Propagation Patterns

Problem The damage in the microtubule lattice grows in a geometrically irregular or unexpected shape that does not align with theoretical predictions.

Investigation & Resolution

| Investigation Step | Action & Parameters to Check |

|---|---|

| Validate Detachment Rates | Review the calculated rates for all possible neighbor configurations ((k{mn})). A dimer's detachment rate increases as it loses neighbors. The rate for a corner dimer ((k{12})) should be the fastest [10]. |

| Account for Seam Dynamics | Check if your model correctly handles seams (lattice defects where α-tubulin meets β-tubulin). A dimer on a seam has three lateral neighbors instead of two, which increases its detachment rate ((k{13} > k{14})) and accelerates fracture propagation along that boundary [10]. |

| Confirm Boundary Conditions | For simulating bulk lattice fracture, ensure both ends of the microtubule are stabilized with a non-detachable cap, preventing depolymerization from the ends from confounding the results [10]. |

Issue 3: Handling Lateral Interactions in the Lattice Model

Problem The model fails to capture collective dynamics or produces results that deviate from mean-field approximations.

Investigation & Resolution

- Process Inclusion: Ensure all relevant elementary processes are included. A model that only includes dimer detachment may be insufficient if reattachment or other local rearrangements are significant in your system [22].

- Lateral Interactions: Confirm whether your model needs to account for explicit lateral interactions between dimers beyond simple neighbor counting. Omitting these can lead to errors in simulating collective behavior [22].

- Code Verification: Use a well-established KMC framework like

kmosto benchmark your custom implementation against a standardized code [22].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: KMC Simulation of Microtubule Fracture from a Monomer Vacancy

This protocol details how to set up a KMC simulation to model fracture propagation from an initial monomer vacancy in a stabilized GDP-microtubule, based on the methodology from recent research [10].

1. System Setup and Lattice Definition

- Construct a two-dimensional lattice representing 13 protofilaments.

- Define the lattice length (e.g., corresponding to a 10 µm microtubule).

- Assign α- and β-tubulin monomers to their positions, identifying the single seam of the B-lattice and any additional seams arising from defects.

- Stabilize both ends of the microtubule by defining the first and last few dimers as non-detachable.

2. Parameter Initialization Populate the following table with the required energy and rate parameters:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (Example) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Binding Energy | (\Delta G_{\text{long}}) | - | Energy per longitudinal monomer contact [10]. |

| Lateral Binding Energy | (\Delta G_{\text{lat}}) | - | Energy per lateral monomer-monomer contact [10]. |

| Lattice Anisotropy | (A) | ~1.5 | Ratio (\Delta G{\text{long}} / \Delta G{\text{lat}}) [10]. |

| Inverse Temperature | (\beta) | (1/kT) | Inverse thermodynamic temperature [10]. |

| Fundamental Time Constant | (\tau) | - | Time constant related to the off-rate of a corner dimer [10]. |

| Monomer Size | (\eta) | 4 nm | Size of a single tubulin monomer [10]. |

3. Initialization and Execution

- Introduce a single monomer vacancy at the desired location (e.g., within the B-lattice, or adjacent to a seam).

- At each KMC step:

- Catalog Events: Identify all dimers on the boundary of any vacancy and calculate their individual detachment rates (k{mn}) using Equation (3).

- Select Event: Calculate the total rate (R{\text{tot}} = \sum k{mn}). Choose a event with probability (k{mn}/R{\text{tot}}) using a random number.

- Advance Time: Increment the simulation clock by (\Delta t = -\ln(r)/R{\text{tot}}), where (r) is a uniform random number between 0 and 1.

- Update Lattice: Execute the chosen dimer detachment event, updating the lattice structure and the list of available events.

- Continue the loop until the damage spans all 13 protofilaments, marking complete fracture.

Quantitative Data from Microtubule Fracture Studies