Machine Learning in Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Analysis: From Biomarker Discovery to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of machine learning (ML) with cytoskeletal gene expression analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning in Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Analysis: From Biomarker Discovery to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of machine learning (ML) with cytoskeletal gene expression analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational role of the cytoskeleton in age-related diseases, details methodological workflows from data processing to model training, and compares the performance of various ML algorithms like SVM and Random Forest. The content also addresses troubleshooting common challenges in feature selection and data integration, validates findings through differential expression analysis and cross-validation, and discusses the translational potential of identified cytoskeletal gene signatures as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for conditions including Alzheimer's disease, cardiomyopathies, and Type 2 Diabetes.

The Cytoskeleton's Role in Aging and Disease: A Primer for Genomic Analysis

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, intricate network of protein filaments that forms a fundamental structural framework within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells [1] [2]. This complex system is far from a static scaffold; it is a dynamic structure that undergoes continuous remodeling, allowing the cell to maintain its shape, withstand mechanical stress, organize its internal contents, and facilitate crucial processes such as cell division, motility, and intracellular transport [3] [2]. Comprising three primary classes of filaments—microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules—the cytoskeleton integrates mechanical and signaling functions to support cellular viability and function [1] [4]. The integrity of this network is so vital that its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cardiomyopathies, and cancer [4] [3] [2]. Contemporary research, leveraging advanced computational approaches like machine learning, has begun to systematically decode the relationship between cytoskeletal gene expression patterns and the pathogenesis of such age-related diseases, opening new avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [4].

Component Analysis: Structure, Function, and Associated Proteins

The distinct biophysical and functional properties of the three cytoskeletal filaments allow them to collectively determine cellular mechanics and organization.

Microfilaments (Actin Filaments)

Structure: Microfilaments are the narrowest components of the cytoskeleton, with a diameter of approximately 7 nm [1] [2]. They are composed of globular actin (G-actin) subunits that polymerize to form a double-stranded helix of filamentous actin (F-actin) [2]. Their dynamics are powered by ATP, enabling rapid assembly and disassembly [1]. Function: These filaments are paramount for maintaining cell shape, particularly at the cortex beneath the plasma membrane [5]. They facilitate whole-cell movement and, in conjunction with the motor protein myosin, are responsible for muscle contraction [1] [2]. During cell division, they form the contractile ring that pinches the cell in two during cytokinesis [3] [5]. Associated Proteins: The actin-based motor protein myosin generates force by walking along microfilaments [1]. The Rho family of small GTPases (Rho, Rac, Cdc42) act as master regulators of actin dynamics, controlling the formation of stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia [6] [2].

Intermediate Filaments

Structure: Intermediate filaments have an average diameter of 10 nm, intermediate between microfilaments and microtubules [7] [2]. They are composed of a diverse family of fibrous proteins (e.g., keratins, vimentin, desmin, lamins, neurofilaments) that assemble into stable, rope-like structures [1] [2]. Unlike other filaments, they are not polarized and do not require nucleotide hydrolysis for their assembly. Function: Their primary role is to provide mechanical strength and reinforce the cell, enabling it to withstand tension and mechanical stress [1] [3]. They are crucial for anchoring organelles, such as the nucleus, in place and form the nuclear lamina that provides structural support to the nuclear envelope [2]. Associated Proteins: Intermediate filaments associate with desmosomes and hemidesmosomes, forming cell-cell and cell-matrix junctions that distribute mechanical load across tissues [2].

Microtubules

Structure: Microtubules are the largest cytoskeletal filaments, with a diameter of about 25 nm [1]. They are hollow cylinders composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that assemble into linear protofilaments [2]. They exhibit dynamic instability, growing and shrinking through GTP hydrolysis, and are typically nucleated from the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC), or centrosome [1]. Function: Microtubules resist compression and provide a network of "highways" for the intracellular transport of vesicles, organelles, and other cargo [3] [5]. During cell division, they form the mitotic spindle that segregates chromosomes [2]. They are also the structural core of cilia and flagella [1]. Associated Proteins: The motor proteins kinesin (typically moves toward the cell periphery) and dynein (typically moves toward the cell center) transport cargo along microtubules [3] [5]. Centrosomes and centrioles help organize the microtubule network [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Cytoskeletal Components

| Property | Microfilaments | Intermediate Filaments | Microtubules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~7 nm [2] | ~10 nm [7] [2] | ~25 nm [1] [2] |

| Protein Subunit | Actin (G-actin) [2] | Keratin, Vimentin, Desmin, Lamins, Neurofilaments [1] [2] | α-tubulin and β-tubulin heterodimers [1] [2] |

| Motor Proteins | Myosin [1] [2] | None known | Kinesin, Dynein [3] [5] |

| Nucleotide Used | ATP [1] | None | GTP [2] |

| Primary Function | Cell shape, motility, contraction [3] | Mechanical strength, resistance to stress [1] [3] | Intracellular transport, cell division, structural support [3] [5] |

Quantitative Profiling in Disease and Machine Learning Analysis

Dysregulation of the cytoskeleton is a key feature in many age-related diseases, and modern research uses transcriptomic analysis to uncover these associations. A 2025 integrative machine learning study analyzed transcriptional changes of 2,304 cytoskeletal genes across five age-related diseases: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), Alzheimer's Disease (AD), Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM), and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) [4].

The study employed Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers alongside Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify a minimal set of cytoskeletal genes that could accurately discriminate between patient and normal samples [4]. The SVM model achieved the highest accuracy among tested algorithms, and the RFE-SVM pipeline identified 17 key cytoskeletal genes associated with these diseases [4]. Differential expression analysis validated these computational findings.

Table 2: Cytoskeletal Genes Associated with Age-Related Diseases Identified via Machine Learning

| Disease | Associated Cytoskeletal Genes |

|---|---|

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) | ARPC3, CDC42EP4, LRRC49, MYH6 [4] |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | CSNK1A1, AKAP5, TOPORS, ACTBL2, FNTA [4] |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | ENC1, NEFM, ITPKB, PCP4, CALB1 [4] |

| Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM) | MNS1, MYOT [4] |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) | ALDOB [4] |

Furthermore, the analysis revealed shared cytoskeletal genes across different diseases, suggesting common pathological pathways. For instance, ANXA2 was dysregulated in AD, IDCM, and T2DM, while TPM3 was common to AD, CAD, and T2DM, and SPTBN1 was shared by AD, CAD, and HCM [4]. These genes represent potential high-value targets for further diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Experimental Protocols for Cytoskeletal Analysis

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Cytoskeletal Gene Signature Identification

This protocol outlines the computational pipeline for identifying cytoskeletal gene biomarkers from transcriptomic data, as demonstrated in recent research [4]. Application: Identification of diagnostic cytoskeletal gene signatures in age-related diseases. Materials:

- RNA-seq or microarray datasets from disease and control cohorts.

- Computational environment (e.g., R, Python).

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Preprocessing: Obtain transcriptome data for the disease of interest from public repositories like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Merge multiple datasets if necessary and perform batch effect correction and normalization using tools like the Limma package in R [4].

- Define the Cytoskeletal Gene Set: Compile a list of genes associated with the cytoskeleton. This can be done using the Gene Ontology term GO:0005856 (approximately 2,300 genes) [4].

- Feature Selection with Machine Learning:

- Train multiple classifier algorithms (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors) using expression values of the cytoskeletal genes.

- Apply Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with the best-performing classifier (SVM is recommended based on published results [4]) to iteratively identify the smallest set of genes that maintains high predictive accuracy for distinguishing disease from control samples.

- Differential Expression Analysis (DEA): Independently, perform DEA (e.g., using DESeq2 or Limma) between patient and normal samples to identify cytoskeletal genes with statistically significant expression changes [4].

- Validation: Validate the discriminatory power of the final set of overlapping genes (from RFE and DEA) using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis on an external validation dataset [4].

Protocol 2: 3D Architectural Analysis of Intermediate Filament Networks

This protocol describes a methodology for quantitatively mapping the three-dimensional organization of intermediate filaments in cells, providing insights into their cell-type-specific roles [7]. Application: Quantitative analysis of intermediate filament network morphology and density in different cell types or disease states. Materials:

- Cell lines or tissue sections (e.g., MDCK cells, HaCaT keratinocytes, RPE cells).

- Fluorescence microscope (confocal recommended) with high-resolution imaging capabilities.

- Image analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ, commercial 3D rendering software).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Labeling: Label the intermediate filament network of interest. This can be achieved by immunostaining with antibodies against specific intermediate filament proteins (e.g., Keratin 8) or by expressing fluorescently tagged versions of the protein (e.g., K8-GFP) [7].

- High-Resolution 3D Imaging: Acquire high-resolution z-stack images of the labeled cells using confocal microscopy to capture the entire volume of the intermediate filament network in three dimensions [7].

- Network Digitization and Modeling: Use specialized image analysis tools to convert the fluorescence images into digitized 3D models of the filament network. This process traces the filaments to create a quantitative spatial representation [7].

- Quantitative Morphometric Analysis: Analyze the 3D models to extract key network properties at different scales:

- Cellular Scale: Assess global network organization, density, and spatial distribution (e.g., differences between apical and basal networks) [7].

- Subcellular Scale: Quantify properties like filament length, orientation, and branching patterns [7].

- Molecular Scale: Convert digital representations into biochemical quantities, such as estimating the total mass of the filament protein present in the cell [7].

Protocol 3: Analyzing Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Live Lymphatic Endothelial Cells

This protocol is adapted from recent research on the dynamic cytoskeletal regulation of cell shape in response to mechanical forces [6]. Application: Investigation of real-time actin and microtubule remodeling during isotropic stretch and cell shape changes. Materials:

- Primary Lymphatic Endothelial Cells (LECs).

- Transgenic reporter mice (e.g., VE-cadherin-GFP, iMb2-Mosaic) for in vivo studies [6].

- Live-cell imaging system (e.g., spinning disk confocal).

- Equipment for applying cyclic isotropic stretch to cells.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Labeling: Culture primary LECs. For actin and microtubule visualization, transfert cells with fluorescent probes (e.g., LifeAct for F-actin, GFP-tagged tubulin for microtubules).

- Intravital Imaging (Optional): For in vivo context, use mice with fluorescent cytoskeletal or membrane labels. Perform longitudinal intravital imaging of the tissue of interest (e.g., mouse ear skin) to observe dynamic remodeling of the cytoskeleton and cellular overlaps during homeostasis and in response to interventions like intradermal fluid injection [6].

- Application of Mechanical Stress: Subject cultured LECs to cyclic isotropic stretch using a specialized cell stretching device to mimic physiological forces like those from interstitial fluid pressure [6].

- Time-Lapse Imaging and Analysis: Conduct live-cell time-lapse microscopy during stretch cycles. Track changes in:

- Pharmacological/Genetic Perturbation: Inhibit key regulators like the Rho GTPase CDC42 (e.g., using small molecule inhibitors or siRNA) to assess their role in cytoskeletal-mediated cell shape control and monolayer stability [6].

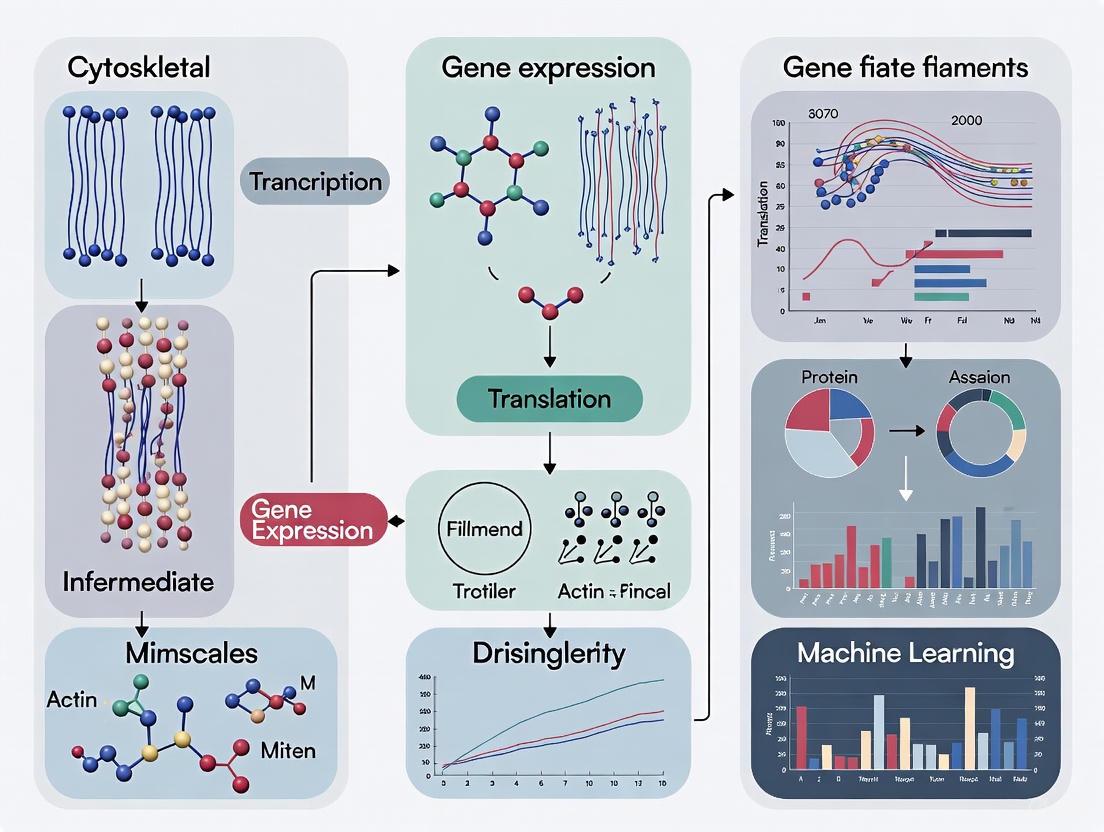

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Machine Learning Analysis of Cytoskeletal Genes

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for identifying cytoskeletal gene biomarkers.

Title: ML Workflow for Cytoskeletal Gene Biomarkers

3D Analysis of Intermediate Filament Networks

This workflow outlines the key steps for the quantitative 3D architectural analysis of intermediate filament networks.

Title: 3D Analysis of Intermediate Filaments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cytoskeletal Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Keratin 8 Antibody | Specific labeling of keratin intermediate filaments for visualization and quantification. | Immunostaining of epithelial cells to analyze intermediate filament network organization and integrity [7]. |

| LifeAct-TagGFP2 | A peptide that binds F-actin, allowing for live-cell imaging of dynamic actin cytoskeleton remodeling. | Visualizing actin dynamics at the leading edge of migrating cells or in response to mechanical stretch [6]. |

| VE-cadherin-GFP Mouse Model | A transgenic model that expresses GFP-tagged VE-cadherin, enabling in vivo visualization of endothelial cell junctions. | Studying the spectrum of junctional configurations and their dynamics in lymphatic capillary endothelial cells [6]. |

| iMb2-Mosaic Reporter | A tool for stochastic, multi-color labeling of cell membranes, allowing for clear distinction of individual cell shapes and overlaps. | Mapping complex cell shapes and quantifying cell-cell overlap areas in tissues like the lymphatic endothelium [6]. |

| siRNA against CDC42 | Silences the expression of the Rho GTPase CDC42, a key regulator of actin dynamics and cell shape. | Functional validation of CDC42's role in controlling cytoskeletal-driven cell shape and monolayer stability [6]. |

| ML-7 (Myosin Light Chain Kinase Inhibitor) | A specific inhibitor of myosin II ATPase activity, used to disrupt actomyosin contractility. | Probing the role of myosin-driven contractility in cellular tension generation and morphological changes [2]. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | A microtubule-stabilizing drug that suppresses dynamic instability. | Investigating the role of microtubule dynamics in intracellular transport, cell division, and maintaining cell shape [3] [2]. |

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filamentous proteins, is fundamental to maintaining cellular structure, facilitating intracellular transport, and enabling mechanical signaling. A growing body of evidence implicates cytoskeletal instability as a critical driver in the pathogenesis of diverse age-related diseases [8] [9]. Despite differing clinical manifestations, conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), cardiomyopathies, and diabetes share common pathways of cytoskeletal dysregulation, leading to organelle dysfunction, impaired cellular trafficking, and loss of tissue integrity [9] [10]. This application note explores the molecular mechanisms linking cytoskeletal defects to these pathologies and provides detailed experimental protocols for investigating cytoskeletal dynamics, leveraging machine learning approaches to identify novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Cytoskeletal Dysregulation in Age-Related Diseases

Alzheimer's Disease: Tau Pathology and Neuronal Instability

In Alzheimer's disease, the cytoskeletal system undergoes profound disruption, primarily driven by the pathological transformation of the microtubule-associated protein tau. Under physiological conditions, tau stabilizes microtubules, which are essential for maintaining axonal integrity and facilitating intracellular transport [8]. In AD, tau undergoes aberrant post-translational modifications (PTMs)—including hyperphosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination—leading to its detachment from microtubules and subsequent aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [8]. This pathological cascade results in:

- Microtubule Collapse: Dissociation of hyperphosphorylated tau from microtubules triggers their destabilization, impairing axonal transport and leading to synaptic dysfunction [8].

- Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling: Pathological tau disrupts Rho GTPase-regulated actin polymerization, contributing to dendritic spine loss and synaptic failure [8].

- Prion-like Propagation: Liberated tau oligomers propagate trans-neuronally, spreading cytoskeletal instability and neurotoxicity throughout neural networks [8].

The spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology (Braak staging) closely parallels trajectories of cognitive decline and brain atrophy, positioning cytoskeletal instability as a central executor of neurodegeneration rather than a secondary consequence [8] [11].

Cardiomyopathies: Sarcomeric Disintegration and Mechanical Dysfunction

Cardiomyopathies—including hypertrophic (HCM), dilated (DCM), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)—are characterized by structural and functional damage to the myocardium, often stemming from mutations in genes encoding cytoskeletal and sarcomeric proteins [12] [10]. The cardiac cytoskeleton provides mechanical stability, facilitates force transmission, and supports mechanotransduction. Key pathological mechanisms include:

- Sarcomeric Protein Mutations: Mutations in genes encoding sarcomere proteins such as beta-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), myosin-binding protein C (MYBPC3), and troponin T2 (TNNT2) disrupt contractile function, leading to HCM [12].

- Cytoskeletal Cross-Linker Defects: Aberrations in actin-binding and cross-linking proteins, including alpha-actinin 2 (ACTN2), filamin C (FLNC), and dystrophin, compromise the mechanical integrity of cardiomyocytes, contributing to DCM and ARVC [10].

- Impaired Force Transmission: Defective cytoskeletal networks hinder efficient force generation and transmission, resulting in ventricular dilation, systolic dysfunction, and arrhythmogenesis [12] [10].

These genetic disruptions highlight the crucial role of the cytoskeleton in maintaining the structural and functional homeostasis of the heart.

Diabetes: Glucose-Induced Cytoskeletal Remodeling

Diabetes mellitus promotes cytoskeletal dysregulation in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and pancreatic β-cells, contributing to both macrovascular and microvascular complications.

- Vascular Smooth Muscle Dysfunction: Elevated glucose levels activate protein kinase C (PKC) and Rho/Rho-kinase signaling pathways, stimulating actin polymerization and enhancing the expression of contractile smooth muscle markers [13] [14]. This hypercontractile state contributes to vascular hyperreactivity, a hallmark of diabetic vasculopathy.

- Pancreatic β-Cell Insulin Secretion: Glucose-induced remodeling of the cortical actin network is essential for the biphasic secretion of insulin [15]. The actin cytoskeleton acts as a dynamic barrier that regulates the access of insulin granules to the plasma membrane; its dysregulation impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, a key defect in type 2 diabetes.

Table 1: Core Cytoskeletal Pathomechanisms in Age-Related Diseases

| Disease | Key Cytoskeletal Components | Primary Dysregulation Mechanisms | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Microtubules, Tau, Actin filaments | Tau hyperphosphorylation, MT dissociation, actin dysregulation | Impaired axonal transport, synaptic loss, cognitive decline |

| Cardiomyopathies | Sarcomeric proteins, ACTN2, FLNC, Dystrophin | Genetic mutations in structural and Z-disc proteins | Reduced contractility, arrhythmias, heart failure |

| Diabetes | Actin networks (VSMC, β-cells) | Glucose-induced Rho/ROCK activation, aberrant polymerization | Vascular hypercontractility, impaired insulin secretion |

Computational Identification of Cytoskeletal Biomarkers

The transcriptional profiling of cytoskeletal genes across age-related diseases reveals common pathways of dysregulation. A recent computational framework employing machine learning identified 17 cytoskeletal genes associated with AD, cardiomyopathies, and diabetes [9]. The methodology integrated:

- Support Vector Machine (SVM) Classification: Achieved the highest accuracy in classifying disease states based on cytoskeletal gene expression patterns [9].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Uncovered significant transcriptional changes in cytoskeletal genes across the target diseases [9].

- Cross-Disease Biomarker Potential: The identified genes are implicated in the structure and regulation of the cytoskeleton, offering promise as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [9].

This integrative analysis provides a holistic overview of how transcriptional dysregulation of cytoskeletal genes contributes to the shared pathophysiology of age-related diseases.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Analyzing Cytoskeletal Gene Expression in Human Tissue

Objective: To quantify expression changes of cytoskeletal genes in post-mortem brain and heart tissues from patients with AD and cardiomyopathy.

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection and Sectioning:

- Obtain fresh-frozen human hippocampus (CA1 and CA3 subfields) and myocardial tissue from donors with documented AD, cardiomyopathy, and non-demented controls [11].

- Cut frozen tissue into 60 μm sections. Stain the first section with cresyl violet for anatomical reference.

- Using a scalpel, microdissect CA1 and CA3 subfields or myocardial regions from subsequent sections on dry ice.

RNA Isolation:

- Extract total RNA using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) with DNase I treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [11].

- Determine RNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). Accept samples with A260/A280 ratios of 1.8-2.0.

- Assess RNA integrity using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA 6000 Nano Chips. Proceed only with samples having RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7.0.

Microarray Processing:

- Analyze 360 ng of total RNA per sample on Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 Expression BeadChips following manufacturer's protocols [11].

- Randomly assign samples to BeadChips to minimize batch effects on differential expression analysis.

Computational Analysis:

- Perform quantile normalization of expression data.

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using a Student's t-test (p < 0.05) combined with fold change > 1.2 [11].

- Conduct weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify modules of highly co-expressed genes associated with disease status [11].

Validation:

- Confirm expression changes of key cytoskeletal genes (e.g., ACTN2, FLNC, Tau isoforms) using TaqMan-based qRT-PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control [16].

- Verify protein-level changes via Western blotting of tissue homogenates using antibodies against proteins of interest.

Protocol 2: Functional Assessment of Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Cell Migration

Objective: To investigate cytoskeletal remodeling and focal adhesion turnover during cell migration using vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture primary human VSMCs (passages 4-7) in M199 medium supplemented with 20% FBS [16].

- For lipid-loading experiments, incubate cells with aggregated LDL (agLDL, 100 μg/mL) for 24 hours.

- To study complement pathway activation, stimulate cells with iC3b fragment (100 nM) for specified durations.

Scratch Wound Migration Assay:

- Grow hVSMCs to confluence in 10 cm culture plates.

- Create uniform linear wounds using a double-sided scrape tool.

- Wash cells with PBS and maintain in migration medium (M199 with 10% FCS) for 4 hours.

- Collect cells from the wound border ("migrating" population) and from areas >500 μm from the wound ("non-migrating" controls) for downstream analysis.

Gene Expression Profiling:

- Extract total RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen).

- Analyze expression of 84 motility-related genes using the Human Motility RT² Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen) [16].

- Validate key hits (e.g., PXN, CTNNB1, FN1) using individual TaqMan assays with GAPDH normalization.

Protein Interaction and Localization Analysis:

- Perform subcellular fractionation to isolate membrane, cytosolic, and cytoskeletal protein fractions.

- Analyze protein distribution via Western blotting using antibodies against paxillin, F-actin, and other cytoskeletal regulators.

- For confocal microscopy, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and immunostain for paxillin and F-actin (using phalloidin).

- Quantify paxillin-F-actin colocalization using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Protocol 3: Investigating Glucose-Induced Cytoskeletal Remodeling

Objective: To examine the effects of elevated glucose on actin polymerization and contractile differentiation in vascular smooth muscle cells.

Procedure:

- Glucose Treatment:

- Isolate VSMCs from mouse aorta by enzymatic digestion.

- Culture cells in DMEM containing varying glucose concentrations: low glucose (1.7 mM), normal glucose (5.5 mM), and high glucose (25 mM) for 1-6 weeks [14].

- Include an osmotic control (low glucose + 23.3 mM mannitol) to distinguish glucose-specific effects from osmotic influences.

Pharmacological Inhibition:

- Treat cells with specific inhibitors during the final 24 hours of glucose exposure:

- Latrunculin B (250 nM): Actin polymerization inhibitor

- Y-27632 (10 μM): Rho-kinase inhibitor

- GF-109203X (10 μM): PKC inhibitor

- Verapamil (1 μM): L-type calcium channel blocker

- Aminoguanidine hydrochloride (100 μM): AGE formation inhibitor

- Use 0.1% DMSO as a vehicle control.

- Treat cells with specific inhibitors during the final 24 hours of glucose exposure:

Gene and Protein Expression Analysis:

- Analyze expression of contractile smooth muscle markers (e.g., Tagln, Cnn1) by qRT-PCR and Western blotting.

- Perform microarray analysis using Affymetrix GeneChip arrays to profile global transcriptional changes.

Functional Assessment:

- Evaluate actin polymerization status through phalloidin staining and quantification of F-actin/G-actin ratios.

- Assess cell viability using MTT assays to exclude cytotoxic effects of inhibitors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | RNeasy Micro/Mini Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality RNA extraction from tissues/cells | Gene expression profiling [16] [11] |

| PCR Arrays | Human Motility RT² Profiler PCR Array | Targeted analysis of cytoskeletal & adhesion genes | Cell migration studies [16] |

| Cytoskeletal Inhibitors | Latrunculin B, Y-27632, Cytochalasin D | Disrupt actin polymerization & Rho/ROCK signaling | Mechanistic pathway dissection [15] [14] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Aggregated LDL, iC3b complement fragment | Induce pathological remodeling in VSMCs | Disease modeling [16] |

| Antibodies | Anti-paxillin, Anti-tau, Anti-ACTN2 | Protein detection & localization | Western blot, immunofluorescence [16] [10] |

Signaling Pathways in Cytoskeletal Dysregulation

The molecular pathways connecting extracellular stimuli to cytoskeletal remodeling in age-related diseases share common regulatory nodes:

Rho GTPase Signaling Pathway:

This pathway illustrates how diverse pathological stimuli converge on Rho GTPases to drive cytoskeletal alterations:

- In diabetes, high glucose activates Rho/ROCK signaling, promoting actin polymerization and contractile differentiation in VSMCs [13] [14].

- In Alzheimer's disease, disrupted Rho GTPase signaling contributes to aberrant actin dynamics and dendritic spine loss [8].

- In cardiomyopathies, mutations in cytoskeletal regulators perturb mechanical signaling through Rho-dependent pathways [10].

Cytoskeletal dysregulation represents a convergent pathological mechanism in age-related diseases, with distinct molecular manifestations in neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders. The experimental protocols outlined herein provide robust methodologies for investigating cytoskeletal dynamics across disease contexts, from transcriptional profiling to functional validation. The integration of machine learning approaches with traditional experimental techniques offers powerful strategies for identifying novel cytoskeletal biomarkers and therapeutic targets. As research in this field advances, targeting cytoskeletal homeostasis may yield innovative interventions for multiple age-related conditions, potentially enabling precision medicine approaches that address shared pathomechanisms rather than isolated disease manifestations.

The cytoskeleton is a critical network of intracellular filamentous proteins that maintains cellular shape, enables intracellular transport, and facilitates cellular motility. Curating a precise set of genes associated with this structure is a fundamental step in systems biology and genomic research, particularly for investigations into age-related diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and drug target discovery. The Gene Ontology (GO) term GO:0005856 provides a standardized, community-defined reference for "cytoskeleton," describing "any of the various filamentous elements that form the internal framework of cells" [17]. This application note details a comprehensive protocol for curating cytoskeletal genes using GO:0005856 and integrated genomic databases, with a specific focus on supporting machine learning (ML) analysis of cytoskeletal gene expression in disease contexts. The framework is designed to equip researchers with the tools to generate robust, reproducible gene sets for downstream transcriptional profiling and biomarker identification.

Application Notes

The Central Role of Cytoskeletal Genes in Disease Research

Cytoskeletal integrity is essential for numerous cellular processes, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of many pathological conditions. Recent research underscores the critical importance of precisely defined cytoskeletal gene sets in understanding disease mechanisms:

- Age-Related Diseases: A 2025 study employed GO:0005856 to retrieve a cytoskeletal gene set for analyzing transcriptional dysregulation in five age-related diseases: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), Alzheimer's Disease (AD), Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM), and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Machine learning models trained on this gene set successfully classified patient samples, identifying 17 potential cytoskeletal biomarkers for these conditions [4].

- Cardiovascular Pathologies: Research on lipid-loaded human vascular smooth muscle cells (hVSMCs) revealed that migrating cells exhibit distinct gene expression profiles related to cytoskeletal remodeling. Six key genes—PXN, AKT1, RHOA, VCL, CTNNB1, and FN1—were identified as central to focal adhesion and cytoskeletal dynamics, with PXN occupying a pivotal position in the interaction network [18] [16]. This finding highlights the role of cytoskeletal genes in atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling.

- Therapeutic Targeting: The ability to pinpoint specific cytoskeletal genes involved in disease pathways, such as the complement C3-mediated signaling via integrin complexes, opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [18].

Database Curation and Gene Set Characteristics

Utilizing GO:0005856 as a root term, researchers can retrieve cytoskeletal gene sets from multiple authoritative databases. The table below summarizes the characteristics of gene sets available from prominent sources.

Table 1: Genomic Databases for Cytoskeletal Gene (GO:0005856) Curation

| Database | Gene Count | Scope & Annotations | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology Browser | 2,304 genes [4] | Comprehensive; includes microfilaments, intermediate filaments, microtubules, and associated polymers [4]. | Foundational list generation for large-scale OMICs studies and machine learning. |

| MSigDB (CYTOSKELETON) | 367 genes [17] | Curated; based on the GO term GO:0005856 [17]. | Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and pathway-focused transcriptomic studies. |

| LOCATE Database | 183 proteins [19] | Experimentally validated; includes proteins localized to the cytoskeleton via high- or low-throughput assays [19]. | Validation of subcellular localization and building high-confidence interaction networks. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Foundational Curation of Cytoskeletal Genes

This protocol outlines the steps to acquire and validate a core set of cytoskeletal genes from public databases for subsequent analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- Computer with internet access and standard web browser.

- R statistical software with

Bioconductorpackages (e.g.,limma,DESeq2) installed for data normalization and differential expression analysis [4]. - Cytoscape software (v3.10 or higher) for network visualization and analysis [18] [20].

Procedure

Gene Set Retrieval:

- Navigate to the Gene Ontology Browser (http://geneontology.org/) or the MSigDB website (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/).

- Search for the term "GO:0005856" or the gene set "CYTOSKELETON".

- Download the gene list in a convenient format (e.g.,

.grp,.gmt, or.txt). The initial set will contain over 2,300 genes [4].

Data Integration and Filtering (Optional):

- For a more focused list, cross-reference the downloaded set with experimentally validated proteins from the LOCATE database [19].

- Filter the list based on specific research goals, such as focusing on actin-binding proteins or microtubule-associated factors.

Functional and Network Analysis:

- Import the finalized gene list into the Cytoscape platform.

- Use the STRING app within Cytoscape to fetch known and predicted protein-protein interactions from integrated databases [18] [16].

- Perform gene ontology enrichment analysis using tools like ShinyGO (https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/) to identify overrepresented biological processes and pathways within your curated gene set [18].

Protocol 2: A Machine Learning Workflow for Cytoskeletal Biomarker Discovery

This protocol describes a validated computational pipeline for identifying cytoskeletal gene signatures from transcriptomic data of patient samples [4].

Materials and Reagents

- Normalized transcriptome datasets from disease and control samples (e.g., from GEO or ArrayExpress).

- Python programming environment with scikit-learn, or R with corresponding ML libraries.

Procedure

Data Preprocessing:

- Retrieve relevant public or in-house transcriptomic datasets for your disease of interest.

- Perform batch effect correction and normalization using the Limma package in R [4].

Feature Selection with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE):

- Subset the normalized expression data to include only the curated cytoskeletal genes from Protocol 1.

- Utilize RFE with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier in a wrapper approach. The SVM classifier has been shown to achieve the highest accuracy for this task [4].

- Recursively remove the least important features with a small step size (e.g., starting with one feature) to identify the minimal, most discriminative subset of cytoskeletal genes that differentiate disease from control samples.

Model Training and Validation:

- Train the SVM classifier using the RFE-selected gene features.

- Assess model performance using five-fold cross-validation, evaluating metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, recall, and precision [4].

- Validate the predictive power of the gene signature on an independent, external dataset using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis:

- In parallel, perform differential expression analysis on the full cytoskeletal gene set between patient and control groups using tools like DESeq2 or Limma.

- Identify the overlapping genes between the RFE-selected features and the significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs). These high-confidence candidates are strong contenders for disease-associated cytoskeletal biomarkers [4].

Diagram: Computational Workflow for Cytoskeletal Biomarker Discovery

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation of Cytoskeletal Gene Expression

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for validating the role of candidate cytoskeletal genes in a cell migration model, as applied in recent vascular biology studies [18] [16].

Materials and Reagents

- Primary human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (hVSMCs).

- Cell culture medium (M199 with 20% FBS).

- Aggregated LDL (agLDL) prepared by vortexing plasma-purified LDL [18].

- iC3b complement fragment.

- RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) for RNA extraction.

- High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit.

- TaqMan Real-Time PCR assays (e.g., PXN: Hs01104424_m1).

- RIPA buffer for protein extraction.

- Antibodies for Western Blot (e.g., anti-PXN).

- Paraformaldehyde (4%) for cell fixation.

- Confocal microscope.

Procedure

Cell Culture and Treatment:

Scratch-Wound Assay:

- Create a uniform scratch wound in a confluent cell monolayer using a sterile pipette tip.

- After washing, maintain cells in migration medium (M199 with 10% FCS) for 4 hours.

- Collect cells that have migrated into the wound area ("migrating cells") and cells distant from the wound ("non-migrating cells") separately for analysis [18].

Gene Expression Analysis (RT-qPCR):

- Extract total RNA from migrating and non-migrating cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit.

- Synthesize cDNA and perform real-time PCR using TaqMan assays for target genes (e.g., PXN, CTNNB1, FN1).

- Normalize expression levels using housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) and analyze via the 2−ΔΔCt method [18] [16].

Protein Analysis and Localization:

- Perform Western blotting on total protein extracts to confirm changes in protein expression (e.g., reduced PXN levels in migrating cells).

- For confocal microscopy, seed treated cells on coated dishes, fix with 4% paraformaldehyde at specific time points, and immunostain for proteins of interest (e.g., PXN) and F-actin.

- Quantify protein distribution and colocalization (e.g., PXN-F-actin colocalization, which increased from 1.26% to 19.68% in iC3b-stimulated cells [18]).

Diagram: Experimental Validation Workflow for Cell Migration Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cytoskeletal Gene and Protein Analysis

| Item Name | Supplier / Source | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Human Target RT² Profiler PCR Array | Qiagen (PAHS-128Z) | Simultaneously profiles the expression of 84 motility- and cytoskeleton-related genes using real-time PCR [18]. |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen (ref. 74104) | Spin-column technology for high-quality total RNA extraction from cell cultures, essential for downstream transcriptomic analyses [18]. |

| Cytoscape Software | http://cytoscape.org/ | Open-source platform for visualizing molecular interaction networks integrated with gene expression and other functional data [18] [20]. |

| STRING Database / App | Integrated in Cytoscape | Predicts protein-protein interactions, including physical and functional associations, to build and analyze networks around genes of interest like PXN [18]. |

| Aggregated LDL (agLDL) | Prepared in-house from human plasma | Used to model lipid-loading in vascular cells, inducing cytoskeletal remodeling and a migratory phenotype relevant to atherosclerosis [18] [16]. |

| iC3b Complement Fragment | Commercial suppliers | Key signaling molecule used to stimulate complement pathways and study their role in cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration [18]. |

The study of complex biological systems, such as the cytoskeleton's role in health and disease, has entered a data-rich era where traditional analytical methods are no longer sufficient. Cytoskeletal dynamics play a critical role in fundamental cellular processes and are implicated in a wide spectrum of age-related diseases, from neurodegenerative conditions to cancers [9]. Modern transcriptomic and proteomic technologies generate vast, multidimensional datasets that capture intricate molecular relationships, demanding sophisticated computational approaches for meaningful interpretation. This article establishes the foundational imperative for machine learning (ML) in deciphering these complexities, providing concrete examples and actionable protocols for researchers pursuing cytoskeletal gene expression analysis.

The Machine Learning Imperative: From Data to Biological Insight

Machine learning algorithms provide the essential computational framework for identifying subtle, non-linear patterns within high-dimensional biological data that escape conventional statistical methods. In cytoskeletal research, ML enables the transition from mere data collection to genuine mechanistic insight and predictive modeling. The integration of ML is not merely beneficial but has become a necessity for several compelling reasons:

- High-Dimensionality Reduction: ML techniques can process thousands of cytoskeletal-related genes simultaneously to identify a minimal set of biomarkers with prognostic or diagnostic power [21].

- Pattern Recognition in Complex Systems: Algorithms can uncover unique molecular signatures that distinguish specific disease subtypes, such as the specific dysregulation patterns in neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma versus other cervical cancers [22].

- Predictive Model Construction: Supervised learning builds robust models that predict clinical outcomes like overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma or diagnose conditions like diabetic foot ulcers, enabling proactive therapeutic strategies [23] [21].

Quantitative Evidence: ML Successes in Cytoskeletal Analysis

Recent studies demonstrate the transformative impact of ML in cytoskeletal biology. The table below summarizes key findings from recent research that successfully applied machine learning to analyze cytoskeletal and related genes.

Table 1: Machine Learning Applications in Cytoskeletal and Gene Expression Analysis

| Disease Context | ML Algorithm(s) Used | Key Genes/Proteins Identified | Reported Outcome/Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Related Diseases (HCM, CAD, AD, IDCM, T2DM) [9] | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | 17 cytoskeletal genes | SVM achieved the highest accuracy in identifying disease-associated biomarkers. |

| Neuroendocrine Cervical Carcinoma (NECC) [22] | 11 algorithms packaged into 66 combinations (randomForest, SVM-RFE, LASSO) | SCGN, CAP2, CACYBP | Identified key proteins with robust diagnostic ability and specificity for a rare cancer subtype. |

| Diabetic Foot Ulcers (DFU) [23] | LASSO Regression | DCT, PMEL, KIT | Established a diagnostic signature linked to melanin production and MAPK/PI3K-Akt pathways. |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) [21] | LASSO Cox Regression & Random Forest | ARPC1A, CCNB2, CKAP5, DCTN2, TTK | Constructed a robust 5-gene prognostic model validated across independent cohorts. |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Driven Cytoskeletal Research

Protocol 1: Identifying a Cytoskeletal Gene Signature for Disease Prognosis

This protocol outlines the workflow for developing a prognostic gene signature in hepatocellular carcinoma, as demonstrated in the research by [21].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Obtain transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-Seq) and corresponding clinical data (e.g., overall survival) from public repositories like TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) and ICGC.

- Standardize data and convert to a consistent format (e.g., FPKM). Filter for cytoskeleton-related genes from a curated database such as MSigDB.

Differential Expression and Functional Analysis:

- Using the

limmaR package, identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal tissues, or between high- and low-survival groups (divided by median survival), with a significance cutoff of p < 0.05. - Perform functional enrichment analysis (GO and KEGG) on the DEGs using the

clusterProfilerR package to identify overrepresented biological pathways.

- Using the

Machine Learning for Prognostic Model Construction:

- Feature Selection: Apply LASSO Cox regression using the

glmnetR package with 10-fold cross-validation to select the most predictive genes while preventing overfitting. - Model Building: Construct a prognostic risk score model. The risk score for each patient is calculated as a linear combination of the expression levels of the selected genes, weighted by their regression coefficients from the LASSO model.

- Validation: Validate the model's performance in one or more independent external cohorts (e.g., ICGC LIRI-JP, CHCC-HBV).

- Feature Selection: Apply LASSO Cox regression using the

Model Performance and Clinical Utility Evaluation:

- Stratification: Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Plot Kaplan-Meier survival curves and perform a log-rank test to assess survival difference between groups using the

survivalR package. - Accuracy: Generate time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) using the

timeROCR package to evaluate the model's predictive accuracy. - Clinical Translation: Integrate the risk score with other clinical variables (e.g., age, stage) in a multivariate Cox regression to assess its independent prognostic value. Build a nomogram to provide a visual tool for predicting individual patient survival probability.

- Stratification: Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Plot Kaplan-Meier survival curves and perform a log-rank test to assess survival difference between groups using the

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in this protocol:

Protocol 2: A Diagnostic Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

This protocol details the integrative approach used to identify specific protein biomarkers for neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma (NECC) [22].

Multi-Omics Data Integration:

- Collect quantitative proteomic data (e.g., from 4D-DIA mass spectrometry) from fresh-frozen NECC tissue and paired paracancerous tissues.

- Retrieve or download public gene and protein expression datasets for NECC and other cervical cancers (e.g., CSCC, ECA) for comparison.

Identification of Disease-Specific Molecular Features:

- Perform differential expression analysis to identify proteins significantly dysregulated in NECC compared to normal tissue.

- Conduct a comparative analysis to pinpoint proteins dysregulated specifically in NECC but not in other common cervical cancer subtypes, revealing unique biological characteristics.

Multi-Algorithm Machine Learning Screening:

- Package multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., randomForest, SVM-RFE, LASSO) into dozens of computational combinations.

- Run all algorithm combinations to screen the candidate proteins from Step 2. Select the optimal algorithm based on performance metrics.

- Define the final set of key proteins (e.g., SCGN, CAP2, CACYBP) that form the core diagnostic signature.

Experimental Validation and Functional Characterization:

- Validation: Confirm the expression and localization of the key proteins using immunohistochemical (IHC) staining on an independent set of patient samples.

- Specificity Check: Analyze the expression patterns of the key genes in other, related neuroendocrine carcinomas to verify the uniqueness of the NECC signature.

- Functional Insight: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., STRING database) to explore protein-protein interaction networks and perform functional enrichment analysis to understand the biological role of the key proteins, such as their involvement in cytoskeleton protein binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal ML Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| TCGA & ICGC Datasets | Provide large-scale, well-annotated transcriptomic and clinical data for model training and validation [21]. |

| MSigDB Cytoskeleton Gene Set | A curated list of cytoskeleton-related genes used to filter and focus the analysis on the biological system of interest [21]. |

| R Packages (limma, glmnet, survival, timeROC) | Core software tools for differential expression analysis, ML model construction, survival analysis, and model performance evaluation [23] [21]. |

| 4D-DIA Mass Spectrometry | Advanced proteomic technology for high-throughput, quantitative protein profiling from tissue samples [22]. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Reagents | Used for orthogonal validation of protein expression and localization in patient tissue sections, bridging computational findings with morphological context [22]. |

| STRING Database | Online resource for predicting and analyzing protein-protein interaction networks, providing functional context for candidate biomarkers [23] [21]. |

Visualizing the Signaling Pathways in Cytoskeleton-Related Disease

The application of ML in cytoskeletal analysis often reveals genes involved in critical signaling pathways. The diagram below synthesizes a common pathway where cytoskeletal dynamics, influenced by key genes, contribute to disease processes like cancer progression and impaired wound healing. This integrates findings on the MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways from diabetic foot ulcer research [23] with the general role of cytoskeletal dysregulation in cancer [9] [21].

The integration of machine learning into the analysis of cytoskeletal genes is no longer an optional advanced technique but a fundamental requirement for progress in biomedical research. The protocols and evidence presented provide a roadmap for researchers to harness these computational tools, transforming large-scale omics data into diagnostic signatures, prognostic models, and deeper functional insights. As the field evolves, this synergy between computational biology and experimental validation will be paramount in driving the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and advancing personalized medicine for a range of cytoskeleton-associated diseases.

Building the Analysis Pipeline: Machine Learning Workflows for Cytoskeletal Transcriptomics

In transcriptomic studies, the accuracy of biological interpretation, especially in complex investigations such as machine learning-based analysis of cytoskeletal gene expression, is heavily dependent on robust data preprocessing. Technical variations introduced during sample processing, sequencing runs, or experimental batches can create non-biological patterns that obscure true biological signals. The limma package in R/Bioconductor provides a comprehensive framework for addressing these challenges, offering integrated solutions for normalization and batch effect correction that are essential for ensuring data quality before downstream machine learning analysis. This protocol details the application of limma for preprocessing transcriptomic data, with a specific focus on preparing data for cytoskeletal gene expression analysis in age-related diseases and cancer.

Table 1: Common Sources of Batch Effects in Transcriptomic Studies

| Source Type | Examples | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | Different sequencing runs, library preparation protocols, reagents, instruments | Systematic shifts in expression distributions between batches |

| Biological | Sample collection times, different operators, multiple donors | Unwanted variation that can confound biological conditions of interest |

| Procedural | RNA extraction methods, enrichment protocols (polyA vs. ribo-depletion) | Compositional biases affecting gene expression measurements |

Theoretical Foundation of Limma

Statistical Philosophy and Design

Limma operates on a modular framework that combines linear modeling with empirical Bayes methods to analyze gene expression data from diverse platforms, including microarrays and RNA-seq. The package's core strength lies in its ability to fit a separate linear model for each gene while borrowing information across genes to stabilize inferences, particularly beneficial for studies with small sample sizes. This approach allows researchers to model complex experimental designs, account for multiple factors simultaneously, and make reliable statistical inferences even with limited replicates [24].

The empirical Bayes methods in limma implement a sophisticated information-borrowing strategy where estimated variances for each gene become a compromise between gene-specific variability and global variability across all genes. This moderation effectively increases the degrees of freedom for variance estimation, producing more stable and reliable results. Recent enhancements to limma have incorporated mean-variance trend modeling, which is particularly important for technologies that produce data with intensity-dependent variability, and robust empirical Bayes procedures that handle hyper-variable genes more effectively [24].

The Voom Transformation for RNA-Seq Data

For RNA-seq count data, limma utilizes the voom (precision weights) transformation to convert raw counts into log2-counts per million (log-CPM) with associated precision weights. This transformation enables the application of limma's established linear modeling framework to count-based data by:

- Modeling the mean-variance relationship in the data

- Assigning appropriate weights to each observation based on its predicted variance

- Unlocking the use of limma's full suite of linear modeling tools for RNA-seq data [24]

The voom approach has demonstrated performance comparable to negative binomial-based methods while offering greater computational efficiency and reliability for large datasets, making it particularly suitable for extensive machine learning studies on cytoskeletal genes [24].

Experimental Design and Data Acquisition Considerations

Effective preprocessing begins with proper experimental design. For studies investigating cytoskeletal gene expression patterns, careful planning can minimize batch effects before computational correction:

- Replicate Structure: Ensure that biological conditions of interest are represented across multiple batches

- Randomization: Process samples from different experimental groups in random order

- Balanced Design: Distribute technical factors (e.g., sequencing lane, processing date) evenly across biological conditions

- Metadata Collection: Document all potential batch variables meticulously for inclusion in statistical models

Table 2: Essential Metadata to Record for Batch Effect Correction

| Category | Specific Variables | Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Information | Biological condition, replicate ID, donor characteristics | Primary variables of interest |

| Technical Processing | RNA extraction date, library preparation batch, operator ID | Potential batch effects |

| Sequencing Details | Sequencing run date, lane allocation, flow cell ID, read depth | Technical covariates |

| Quality Metrics | RIN scores, alignment rates, unique molecular identifiers | Quality control and weighting |

Normalization Protocols with Limma

Between-Array Normalization for Microarray Data

For two-color microarray data, limma provides comprehensive normalization functions:

The normalizeBetweenArrays function offers multiple methods:

- Quantile normalization: Forces the distribution of intensities to be identical across arrays

- Scale normalization: Aligns median absolute deviations across arrays

- Loess normalization: Suitable for two-color arrays with intensity-dependent dye biases

Normalization of RNA-Seq Data with Voom

For RNA-seq count data, the voom transformation incorporates normalization within its workflow:

The voom function generates a plot showing the mean-variance trend, which should be examined to ensure the transformation is appropriate. The resulting object contains log2-CPM values with precision weights that are incorporated into subsequent linear models.

Batch Effect Correction Workflow

Identifying Batch Effects

Before correction, assess data for batch effects using principal component analysis (PCA):

Clustering of samples by batch rather than biological condition in PCA space indicates significant batch effects requiring correction.

Batch Effect Correction Using Limma

Limma corrects batch effects by including batch as a covariate in the linear model:

This approach simultaneously models batch effects and biological conditions of interest, effectively adjusting for batch while testing for differential expression.

Integration with ComBat-seq for RNA-Seq Data

For severe batch effects in RNA-seq data, limma can be combined with ComBat-seq, which uses a negative binomial model specifically designed for count data:

Recent advancements like ComBat-ref further enhance this approach by selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion and adjusting other batches toward this reference, improving sensitivity in differential expression analysis [25].

Application in Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Analysis

Case Study: Age-Related Diseases

In a recent study investigating cytoskeletal genes in age-related diseases (Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Coronary Artery Disease, Alzheimer's Disease, Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus), limma was employed for batch effect correction and normalization of transcriptome data. The preprocessing pipeline enabled identification of 17 cytoskeletal genes associated with these conditions, which were subsequently validated using machine learning approaches [4] [9].

The specific workflow included:

- Retrieval of 2304 cytoskeletal genes from Gene Ontology (GO:0005856)

- Batch effect correction using limma on multiple datasets

- Differential expression analysis with limma to identify dysregulated cytoskeletal genes

- Integration with machine learning feature selection to prioritize candidate biomarkers

Case Study: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

In hepatocellular carcinoma research, limma was used to identify 110 differentially expressed cytoskeleton-related genes from the TCGA-LIHC dataset. The normalized data enabled construction of a robust 5-gene prognostic model (ARPC1A, CCNB2, CKAP5, DCTN2, TTK) using machine learning algorithms, demonstrating the critical role of proper preprocessing in developing reliable predictive models [21].

Quality Assessment and Validation

Pre- and Post-Correction Visualization

Validate the effectiveness of normalization and batch correction by comparing PCA plots before and after processing:

Successful correction should show reduced clustering by batch while maintaining separation by biological condition.

Quantitative Metrics

Assess correction quality using quantitative metrics:

- Batch Silhouette Width: Measures degree of batch mixing

- Principal Component Regression: Quantifies variance explained by batch before vs. after correction

- Differential Expression Consistency: Checks concordance of results across batches post-correction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Limma R Package | Differential expression analysis, normalization, batch effect correction | Bioconductor [24] [26] |

| sva Package | ComBat-seq for batch effect correction of RNA-seq count data | Bioconductor [25] |

| Cytoskeletal Gene Sets | Reference gene lists for focused analysis | Gene Ontology (GO:0005856) [4] |

| edgeR | RNA-seq normalization and differential expression | Bioconductor [24] |

| DESeq2 | Alternative method for RNA-seq analysis | Bioconductor [4] |

| PCR Arrays | Targeted profiling of cytoskeletal genes | Human Target RT2 Profiler PCR Array [18] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network analysis | string-db.org [18] |

Workflow Diagram

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Issues and Solutions

- Poor Batch Correction: Ensure experimental design includes all conditions in each batch

- Loss of Biological Signal: Avoid over-correction by using reference-based methods like ComBat-ref

- Non-Normal Distributions: Verify normalization method appropriateness through diagnostic plots

- Model Convergence Problems: Check for complete separation or multicollinearity in design matrix

Advanced Applications

For complex studies integrating multiple data types (e.g., cytoskeletal gene expression with protein interaction data), limma's linear modeling framework can be extended to incorporate additional covariates, interaction terms, and complex experimental designs. The precision weights capability allows for incorporation of external quality metrics to down-weight unreliable measurements, further enhancing the robustness of machine learning analyses built on the preprocessed data [24].

This comprehensive protocol for data acquisition, normalization, and batch effect correction using limma provides a solid foundation for subsequent machine learning analysis of cytoskeletal gene expression patterns in various disease contexts, ensuring that biological conclusions are derived from technically sound data preprocessing.

This application note provides a structured protocol for the comparative evaluation of Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) classifiers within the specific context of cytoskeletal gene expression analysis. Cytoskeletal genes play critical roles in cellular structure, motility, and signaling, and their dysregulation is implicated in various age-related diseases [4] [16]. The accurate classification of disease states based on transcriptional profiles of these genes is therefore a crucial task in biomedical research. We present a detailed methodology for model training, validation, and evaluation, supplemented with performance data from a recent study on age-related diseases [4]. The protocols outlined herein are designed to enable researchers to reliably identify optimal classifiers for their specific transcriptomic datasets.

Machine learning (ML) classification algorithms are indispensable tools for analyzing high-dimensional biological data, such as gene expression matrices derived from microarray or RNA sequencing technologies [27]. These algorithms can learn complex patterns from transcriptomic data to classify sample observations, for instance, distinguishing between diseased and healthy states based on gene expression profiles [27] [4]. The selection of an appropriate classifier is paramount, as the performance of different algorithms can vary significantly depending on the data's characteristics, such as the number of features versus samples, noise levels, and class distribution [28].

The cytoskeleton, a network of filamentous proteins, is essential for numerous cellular processes including maintenance of cell shape, division, and migration [29]. Transcriptional dysregulation of cytoskeletal genes is a hallmark of several pathological conditions [4] [16]. Therefore, applying ML models to cytoskeletal gene expression data can uncover novel biomarkers and enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms. This document provides a standardized framework for comparing three widely-used classifiers—SVM, RF, and k-NN—in this specific biological context, focusing on practical implementation and interpretation of results.

Classifier Performance Comparison

A comparative study analyzing transcriptomic data from age-related diseases (including Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Coronary Artery Disease, and Alzheimer's Disease) based on cytoskeletal gene expressions provides clear evidence of performance variations among classifiers [4]. The table below summarizes the performance metrics of SVM, Random Forest, and k-NN from this study.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Classifiers on Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Data [4]

| Classifier | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Balanced Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 94.7% | 95.2% | 94.5% | 94.8% | 94.5% | 0.98 |

| Random Forest | 92.1% | 91.8% | 92.3% | 92.0% | 91.9% | 0.96 |

| k-NN | 89.3% | 88.9% | 89.6% | 89.2% | 89.4% | 0.93 |

In this specific application, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier demonstrated superior performance across all reported metrics, achieving the highest accuracy (94.7%), precision (95.2%), and F1-score (94.8%) [4]. The study attributed this to SVM's capability to handle high-dimensional feature spaces and identify subtle, complex patterns in gene expression data, which is crucial for classifying complex diseases [4]. Furthermore, SVM is known for its effectiveness in scenarios where the number of features (genes) far exceeds the number of samples (patients), a common characteristic of transcriptomic datasets [4] [28].

Random Forest also showed robust performance, leveraging an ensemble of decision trees to reduce overfitting and improve generalization [30] [28]. While slightly less accurate than SVM in this comparison, its inherent feature importance calculation provides valuable biological insights by highlighting genes that most contribute to the classification.

The k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) algorithm, a distance-based instance-learning method, achieved good but comparatively lower performance [28]. Its simplicity can be an advantage, but its performance can be sensitive to the choice of the parameter 'k' (number of neighbors) and the scale of the data, necessitating careful preprocessing [30] [28].

Experimental Protocols

Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection Protocol

Purpose: To prepare cytoskeletal gene expression data for model training and identify the most informative feature subset. Reagents/Software: Gene expression matrix (e.g., from GEO, ArrayExpress), Python/R, Scikit-learn, Limma package [27] [4].

- Data Sourcing: Obtain a labeled gene expression matrix (samples x genes) from a public repository like Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) or ArrayExpress [27]. Ensure sample labels correspond to classes of interest (e.g., Disease vs. Control).

- Cytoskeletal Gene Filtering: Filter the dataset to include only cytoskeletal genes. A standard reference is the Gene Ontology term GO:0005856, which contains approximately 2304 genes associated with the cytoskeleton [4].

- Data Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization techniques (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays) to correct for technical variation. For cross-dataset analysis, use the

Limmapackage in R to correct for batch effects [4]. - Feature Selection with RFE-SVM:

a. Utilize the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method in conjunction with an SVM estimator (

SVCfromsklearn.feature_selection). b. RFE works by recursively removing the least important features (based on model coefficients) and rebuilding the model [4]. c. Use stratified k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) to evaluate the accuracy of the model at each step. d. Select the optimal subset of genes that yields the highest cross-validation accuracy. This step is critical for reducing dimensionality and enhancing model interpretability and performance [4].

Model Training and Validation Protocol

Purpose: To train SVM, Random Forest, and k-NN classifiers and evaluate their performance robustly.

Reagents/Software: Python, Scikit-learn library (sklearn.ensemble, sklearn.svm, sklearn.neighbors).

- Data Partitioning: Split the preprocessed dataset into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a held-out test set (e.g., 20-30%). Maintain class proportions (stratified split) in both sets.

- Classifier Initialization:

- SVM: Use

SVC()from Scikit-learn. Key hyperparameters to tune include the kernel (linear, radial basis function), regularization parameterC, andgamma[4] [28]. - Random Forest: Use

RandomForestClassifier(). Key hyperparameters include the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum depth of trees (max_depth), and the number of features considered for splitting (max_features) [30] [28]. - k-NN: Use

KNeighborsClassifier(). The most critical hyperparameter is the number of neighbors (n_neighbors). The distance metric (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan) should also be considered [30] [28].

- SVM: Use

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Perform hyperparameter optimization using

GridSearchCVorRandomizedSearchCVon the training set with 5-fold cross-validation to find the best parameters for each model. - Model Training: Train each classifier using its optimized hyperparameters on the entire training set.

- Model Evaluation:

a. Predictions: Generate predictions on the held-out test set.

b. Metrics Calculation: Calculate key performance metrics by comparing predictions to true labels:

* Accuracy:

(TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)[30] * Precision:TP / (TP + FP)[30] * Recall (Sensitivity):TP / (TP + FN)[30] * F1-Score:2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall)[30] c. ROC Analysis: Compute the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) to assess the model's ability to discriminate between classes across all classification thresholds [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cytoskeletal Gene Expression Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Gene Set | A definitive list of genes associated with the cytoskeleton for feature filtering. | Gene Ontology ID: GO:0005856 [4] |

| Gene Expression Data | Numeric matrix of gene expression levels across samples for model training. | Public repositories: GEO, ArrayExpress, TCGA [27] |

| Limma Package (R) | A powerful tool for data normalization, batch effect correction, and differential expression analysis of microarray and RNA-seq data [27] [4]. | Bioconductor |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | A comprehensive machine learning library containing implementations of SVM, RF, k-NN, feature selection (RFE), and model evaluation metrics [30] [4]. | pip install scikit-learn |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A wrapper-style feature selection method to identify the most discriminative subset of genes for classification [4]. | sklearn.feature_selection.RFE |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end computational workflow for the analysis of cytoskeletal gene expression data using machine learning classifiers, from data preparation to model evaluation.

Classifier Decision Mechanisms

This diagram provides a simplified, conceptual overview of the fundamental decision-making processes employed by the k-NN, Random Forest, and SVM classifiers.

This application note establishes a standardized protocol for the comparative analysis of machine learning classifiers applied to cytoskeletal gene expression data. The empirical results demonstrate that SVM, when combined with rigorous feature selection methods like RFE, currently provides the highest classification accuracy for distinguishing disease states based on cytoskeletal gene signatures [4]. However, the choice of the optimal model is context-dependent. Researchers are encouraged to apply the detailed protocols and workflows provided herein to their own datasets, as data-specific characteristics may lead to different outcomes. The integration of these computational methods with experimental biology will accelerate the discovery of cytoskeletal biomarkers and therapeutic targets for a range of human diseases.

In the field of machine learning-based biomarker discovery, feature selection stands as a critical preprocessing step to identify the most informative genes or proteins from high-dimensional biological data. The process involves selecting a subset of relevant features for model construction while eliminating redundant or irrelevant variables. For research focused on cytoskeletal gene expression, effective feature selection is paramount due to the vast number of genes involved in cytoskeletal structure and function. High-dimensional transcriptomic data typically contains thousands of genes, but only a small fraction exhibits meaningful associations with disease pathology. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) represent two widely adopted feature selection techniques that help researchers overcome the "curse of dimensionality" and enhance model interpretability without compromising predictive performance [4] [31].

The cytoskeleton, comprising microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules, maintains cellular shape, integrity, and generates forces for cellular motility. Dysregulation of cytoskeletal genes has been implicated in numerous age-related diseases, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), coronary artery disease (CAD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM), and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) [4]. Identifying the specific cytoskeletal genes associated with these conditions requires robust feature selection methods capable of distinguishing true biological signals from background noise in gene expression data.

Core Methodologies: RFE and LASSO

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

RFE is a wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that operates by recursively removing the least important features and building a model with the remaining features. The process continues until all features have been eliminated, and the optimal feature subset is determined based on model performance metrics [32] [31]. A key advantage of RFE is its ability to consider feature interactions during the selection process, rather than evaluating features in isolation.

In practice, RFE can be implemented with various machine learning classifiers, including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and Neural Networks (NN). The algorithm ranks features by their importance, which is calculated differently depending on the classifier used. For instance, with SVM classifiers, feature importance is typically determined by the absolute value of the weight coefficients, whereas Random Forest uses metrics like Gini importance or permutation importance [32] [4].

The standard RFE workflow involves:

- Training a model with all features

- Ranking features by their importance scores

- Removing the least important feature(s)

- Repeating steps 1-3 until no features remain

- Selecting the feature subset that yields optimal model performance

To enhance the stability of feature selection, RFE is often combined with cross-validation (RFE-CV), where the process is repeated across multiple data splits to obtain a consensus ranking [32]. This approach provides more probabilistic estimates of feature importance than rankings based on a single dataset.

LASSO Regression

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) is an embedded feature selection method that incorporates feature selection directly into the model training process through L1 regularization [33]. By adding a penalty term equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients, LASSO effectively shrinks less important feature coefficients to zero, thereby performing feature selection and regularization simultaneously.

The LASSO optimization problem can be formulated as minimizing the following objective function: