Improving Cytoskeletal Reconstitution Assay Reproducibility: From Foundational Principles to Robust Validation

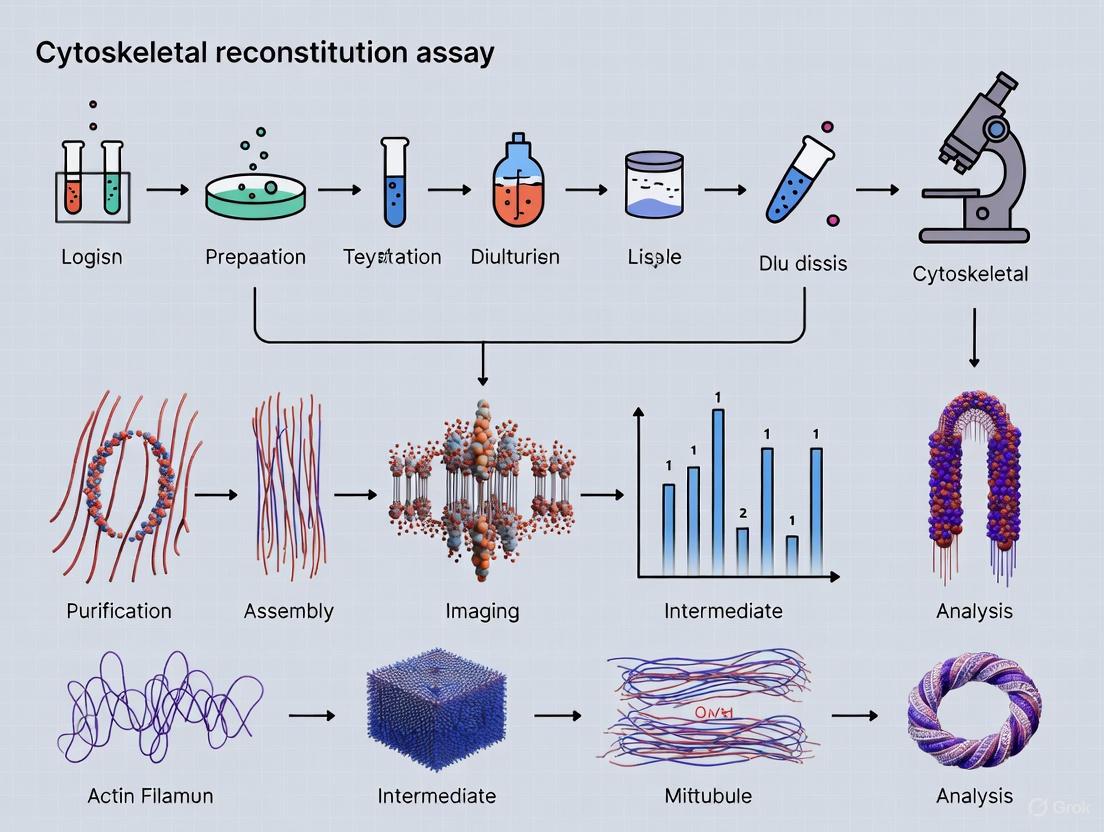

This article provides a comprehensive framework for enhancing the reproducibility of in vitro cytoskeletal reconstitution assays, essential tools for biophysical research and drug development.

Improving Cytoskeletal Reconstitution Assay Reproducibility: From Foundational Principles to Robust Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for enhancing the reproducibility of in vitro cytoskeletal reconstitution assays, essential tools for biophysical research and drug development. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodological protocols, systematic troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation techniques, we address the critical challenge of inter-laboratory variability. By synthesizing recent advances in emergent behavior understanding, context-sensitive factor identification, and novel measurement technologies like QCM-D, this guide empowers researchers to design robust, reliable assays that bridge cell-free studies and cellular physiology for more predictive biomedical applications.

Understanding the Complexity and Reproducibility Challenges in Cytoskeletal Reconstitution

The Fundamental Role of Cytoskeletal Networks in Cellular Mechanics and Dynamics

For researchers investigating cellular mechanics, reconstituted cytoskeletal assays provide an essential window into the fundamental processes that govern cell shape, division, and movement. However, the very dynamic nature of these biopolymer networks—actin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—presents significant challenges for experimental reproducibility. This technical support guide addresses the most common issues encountered when working with reconstituted cytoskeletal systems, providing troubleshooting guidance framed within the context of improving assay reliability for drug development and basic research. The following sections combine foundational principles with practical protocols to help standardize methodologies across laboratories.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why do my reconstituted cytoskeletal networks show inconsistent mechanical properties between experiments?

Issue: Variability in network mechanics despite using identical protein concentrations and buffer conditions.

Explanation: The mechanical properties of reconstituted cytoskeletal networks are highly dependent on their assembly history and final morphology, not just their biochemical composition. These networks often form under kinetic control and become trapped in metastable states far from thermal equilibrium [1]. The competing kinetics of filament elongation, bundling, and crosslinking can lead to dramatically different network architectures even with the same component proteins [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Assembly | Inconsistent polymerization kinetics | Dynamic light scattering or fluorescence monitoring | Standardize incubation times and temperatures; pre-polymerize filaments when appropriate |

| Crosslinking | Variable crosslinker binding efficiency | SDS-PAGE or co-sedimentation assay | Titrate crosslinker concentration; ensure consistent mixing during network formation |

| Composite Networks | Steric interference between polymer species | Confocal microscopy | Stagger polymerization times for different cytoskeletal polymers [1] |

| Motor Activity | Uncontrolled myosin activation | ATP consumption assay | Include ATP-regeneration systems; control nucleotide state precisely |

FAQ 2: How can I effectively visualize cytoskeletal structures without altering their native organization?

Issue: Limitations in imaging fidelity when observing cytoskeletal dynamics, particularly in dense networks.

Explanation: Traditional fluorescence labeling can alter filament dynamics and packing, while many label-free techniques lack the resolution for detailed structural analysis. The choice of imaging method must balance resolution, sampling speed, and minimal invasion to preserve native architecture [2] [3].

Imaging Modalities Comparison:

| Technique | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QWLSI Quantitative Phase Imaging [2] | ~260 nm lateral | Label-free; high-speed (up to 100 fps); works with conventional microscopes | Indirect cytoskeletal visualization | Living cell dynamics; organelle-cytoskeleton interactions |

| Super-resolution SIM [3] | ~110 nm lateral | Multicolor; live-cell compatible; lower phototoxicity | Limited resolution gain; sensitive to aberrations | Actin rings in neuronal axons (MPS); growth cone dynamics |

| Super-resolution STED [3] | ~50-60 nm lateral | High resolution without complex processing; 3D capability | High laser intensities; specific fluorophores required | Dense cytoskeletal arrays; synaptic structures |

| HS-AFM with ML [4] | Single filament | Direct molecular imaging; no labeling required | Surface-limited; specialized equipment | Individual F-actin orientation and branching analysis |

Protocol: Label-Free Cytoskeletal Imaging Using Modified QWLSI [2]

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells on 25 mm type 1.5H glass coverslips at low confluency

- Microscope Setup: Use conventional microscope with halogen Köhler transillumination

- Set illumination numerical aperture to maximum (NAill = 0.52)

- Apply λ = 527±20 nm filter to limit phototoxicity

- Use 100× objective with NAcoll = 1.49

- Image Acquisition: Employ modified Quadriwave Lateral Shearing Interferometry (QWLSI)

- Utilize sCMOS camera at frame rates up to 100 fps

- Average multiple frames to enhance signal-to-noise ratio

- Maintain focus stability with autofocus system

- Data Processing: Measure Optical Path Difference (OPD) and convert to phase information using φ = 2π×OPD/λ

FAQ 3: Why does my actomyosin system show inconsistent contractile behavior?

Issue: Unpredictable contraction patterns in reconstituted actomyosin networks.

Explanation: Actomyosin contractility depends on the precise nucleotide state of both actin and myosin, and is sensitive to the mechanical feedback between these components. Myosin II exhibits a strongly-bound state with actin in the presence of ADP and a weakly-bound state when bound to ATP, with the number of engaged myosin heads directly regulating bundle stiffness [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Test | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| No contraction | Depleted ATP | ATP concentration assay | Fresh ATP; include regeneration system |

| Hyper-contraction | Excessive myosin heads | Myosin:actin ratio titration | Optimize to 1:10 to 1:100 molar ratios |

| Inconsistent timing | Variable nucleotide exchange | Nucleotide state monitoring | Control ADP/ATP ratios precisely |

| Network disintegration | Excessive motor forces | Vary crosslinker density | Increase actin-crosslinking protein concentration |

Protocol: QCM-D for Quantifying Actomyosin Viscoelasticity [5] [6]

- Sensor Preparation: Clean quartz crystal sensors; establish baseline frequency (f) and dissipation (D) in buffer

- Actin Immobilization: Flow in F-actin solution (0.1-1 mg/mL in appropriate buffer)

- Monitor frequency decrease (Δf) indicating mass loading

- Stabilize before proceeding (typically 30-60 minutes)

- Myosin Addition: Introduce myosin II filaments (various molar ratios to actin)

- Include required nucleotide (ATP or ADP)

- Include oxygen-scavenging system for prolonged experiments

- Data Collection: Monitor simultaneous changes in Δf (mass/rigidity) and ΔD (viscoelasticity)

- Contraction typically shows increased -Δf and decreased ΔD

- Relaxation shows opposite patterns

- Nucleotide Switching: Exchange buffer to switch between ATP and ADP states observing real-time mechanical changes

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials for cytoskeletal reconstitution assays:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Polymers | G-actin, tubulin, vimentin | Network backbone structure | Source purity; polymerization competence; nucleotide state |

| Molecular Motors | Myosin II, kinesin, dynein | Force generation; network remodeling | Activity assays; head domain integrity; regulation |

| Crosslinkers | α-actinin, fascin, MAPs | Network connectivity; mechanics | Binding affinity; density optimization; size |

| Nucleotides | ATP, GTP, ADP, GDP | Polymerization dynamics; motor fuel | Purity; regeneration systems; concentration monitoring |

| Imaging Probes | Phalloidin, SiR-actin, immunolabels | Structural visualization | Labeling efficiency; perturbation effects; photostability |

| Buffer Components | Mg²⁺, K⁺, EGTA, PIPES | Ionic environment; stability | Concentration optimization; temperature sensitivity |

Experimental Design and Quality Control Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Reliable Cytoskeletal Reconstitution

Network Architecture Quality Assessment

Network Quality Assessment Parameters

Frequently Asked Questions: Core Concepts

Q1: What makes cytoskeletal reconstitution assays fundamentally challenging to reproduce? The primary challenge lies in the simultaneous control of a large number of interdependent variables. These include the precise concentrations and purity of multiple proteins (actin, tubulin, motor proteins, crosslinkers), the mechanical and chemical properties of the membrane or surface, and the maintenance of non-equilibrium conditions through energy regeneration systems. Small, often unmeasured, variations in any of these parameters can lead to significantly different experimental outcomes [7] [8].

Q2: Are challenges different for actin-based assays versus microtubule-based assays? While the core principles of reproducibility challenges are similar, the specific components and requirements differ. Actin cortex reconstitution often focuses on contractility and network mechanics, heavily influenced by actin-binding proteins, myosin motors, and membrane tethers [7] [9]. Microtubule assays frequently deal with issues of tubulin purity, post-translational modifications, and the activity of complex motors like dynein [10] [11]. Both require distinct, optimized buffers and energy systems.

Q3: What is the most common source of failure for first-time attempts? The inconsistent quality of purified proteins is a very common pitfall. The activity of proteins like actin, myosin, or tubulin can vary between preparations and is highly sensitive to purification and storage conditions. Using proteins from different purification batches without properly controlling for activity is a major source of irreproducibility [10] [9].

Q4: How can our lab improve the reproducibility of our reconstitution experiments? Implementing rigorous quality control for all components is crucial. This includes functional assays for protein activity (e.g., actin polymerization kinetics, motor ATPase activity), standardizing protocols for surface preparation (e.g., supported lipid bilayers), and using internal controls in every experiment, such as a standard condition with known expected behavior [9] [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent Actin or Microtubule Network Morphology

- Symptoms: Networks appear too dense, too sparse, or have variable architecture between experiments.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause Category | Specific Issue | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Quality | Aged or improperly stored actin/tubulin aliquots. | Flash-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C; avoid freeze-thaw cycles [9]. |

| Inactive or variable capping protein. | Check capping activity by quantifying actin filament length distributions in presence of the protein [9]. | |

| Concentration & Purity | Contaminants in purified protein affecting nucleation. | Use high-quality affinity purification methods (e.g., TOG affinity for tubulin) and assess purity via SDS-PAGE [10] [9]. |

| Inaccurate concentration measurements. | Use spectrophotometry with corrected extinction coefficients for each protein [9]. | |

| Assembly Conditions | Uncontrolled nucleation seed formation. | Use purified nucleation factors (e.g., Arp2/3 complex) at consistent concentrations or control filament length with capping protein [7]. |

| Oxidized or degraded nucleotides (ATP/GTP). | Always use fresh, high-purity nucleotides in buffers [5]. |

Problem 2: Lack of Expected Contractility or Motor-Driven Transport

- Symptoms: Actomyosin networks do not contract, or cargo transport by kinesin/dynein is inefficient.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause Category | Specific Issue | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Function | Myosin or dynein motor activity is low. | Perform ATPase activity assays; label motors and confirm they bind to filaments [5] [11]. |

| Incorrect nucleotide state for motor binding. | Ensure proper ATP/ADP levels. Myosin II is strongly bound to actin with ADP, and weakly bound with ATP [5]. | |

| System Composition | Incorrect actin/myosin or tubulin/motor ratios. | Systematically titrate the motor protein concentration to find the optimal range for collective behavior [5]. |

| Missing essential co-factors. | For dynein, ensure the presence of dynactin and an activating adaptor (e.g., BicD2N) for full processivity [11]. | |

| Energy Supply | Depleted ATP/GTP in the system. | Include an energy regeneration system (e.g., creatine phosphate/creatine kinase) to maintain constant nucleotide levels [12]. |

Problem 3: Poor Coupling to Membranes or Surfaces

- Symptoms: Cytoskeletal filaments do not tether properly to supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) or vesicles.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause Category | Specific Issue | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Quality | SLBs are not fluid or contain defects. | Use high-quality small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) and verify bilayer fluidity via FRAP [9]. |

| Incorrect lipid composition for tethering. | Include a specific lipid for tethering, such as DGS-NTA(Ni²⁺) for His-tagged linker proteins [9]. | |

| Linker Protein | Insufficient concentration of membrane-cytoskeleton linker. | Titrate the concentration of the linker protein (e.g., His-tagged ezrin) to find the minimum required for robust coupling [9]. |

| The linker protein itself is inactive or improperly folded. | Express and purify linker proteins with strict quality control; check function with a binding assay [9]. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages and critical control points for a successful membrane-based cytoskeletal reconstitution, helping to visualize where failures often occur.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials required for cytoskeletal reconstitution assays, as cited in the literature.

| Reagent/Component | Function in the Assay | Key Considerations & Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle Actin [9] | The primary building block for actin filaments; can be fluorescently labeled for visualization. | Label with maleimide dyes, not NHS-esters, to avoid non-functional actin. Determine degree of labeling via spectrophotometry. Store in small, flash-frozen aliquots at -80°C. |

| Tubulin (Mammalian Cell-Derived) [10] | The core protein subunit of microtubules. | Purification from HeLa S3 cells provides unmodified tubulin, avoiding the heterogeneity of brain-derived tubulin. Quality is key for controlled PTM studies. |

| Myosin II [5] [9] | The motor protein that generates contractile force on actin filaments. | Purify from skeletal muscle. Label with maleimide dyes. Functional activity can decrease over time; use within 6 weeks when stored at 4°C. |

| Capping Protein [9] | Binds to the barbed ends of actin filaments to control their length and architecture. | Activity must be checked empirically by measuring its effect on actin filament length distribution in a polymerization assay. |

| Membrane-Actin Linker\n(e.g., His-YFP-EzrinABD) [9] | Tethers the actin network to the supported lipid bilayer, mimicking the natural cortex. | Ensure the linker is stable and functional. Store in small aliquots with 20% glycerol at -80°C for long-term stability. |

| Lipids for SLBs\n(e.g., DOPC, DGS-NTA(Ni²⁺)) [9] | Forms the fluid supported lipid bilayer that serves as the synthetic "membrane." | DOPC provides the bilayer structure. DGS-NTA(Ni²⁺) provides binding sites for His-tagged linker proteins. Prepare fresh SUVs via extrusion. |

| Dynein/Dynactin/Adaptor Complex [11] | The complete motor machinery for minus-end-directed microtubule transport. | Full processive transport requires the tripartite complex of dynein, dynactin, and an activating adaptor like BicD2N. |

| Energy Regeneration System [5] [12] | Maintains a steady supply of ATP (or GTP) to keep the system out of equilibrium. | Critical for sustained motor activity and dynamics. Systems often use creatine phosphate and creatine kinase. |

The relationships between these components in a typical membrane-tethered actin cortex assay are illustrated below.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our encapsulated actin structures fail to condense into a single ring and instead form multiple, disorganized clusters. What could be the cause? The most common cause is insufficient membrane binding. Theoretical modeling and experimental data confirm that membrane attachment is crucial for the robust condensation into a single actin ring in spherical vesicles. Ensure you are using an effective membrane anchor system [13].

- Solution: Incorporate a biotin-neutravidin binding system. Use a lipid mixture containing 1% biotinylated lipids and include 4% biotinylated actin in your reaction mix prior to encapsulation. This provides the necessary physical linkage to guide organization [13].

Q2: Actin bundles within our GUVs appear overly stiff and kinked instead of forming smoothly curved structures that follow the membrane. How can this be improved? This is often related to the choice of actin-bundling protein. Different cross-linkers produce bundles with distinct mechanical properties [13].

- Solution: Consider switching the bundling protein. While fascin creates very straight, stiff bundles, proteins like α-actinin or the talin/vinculin combination typically form more flexible bundles that can smoothly follow the membrane curvature [13].

Q3: We observe minimal membrane deformation upon adding myosin motors to our pre-formed actomyosin rings. Why is the system not contracting effectively? This can result from weak coupling between the contractile ring and the membrane. Without a firm anchor, the force generated by myosin is dissipated instead of deforming the vesicle [13].

- Solution: Reinforce the membrane-actin linkage. The talin/vinculin bundling system also functions as a powerful membrane anchor. Using this system can significantly improve force transmission, leading to visible furrow-like deformations during contraction [13].

Q4: Our protein encapsulation efficiency in GUVs is low and inconsistent, harming experiment reproducibility. What methods can improve this? Traditional encapsulation methods are a known challenge. The field has developed advanced techniques to overcome this hurdle [13].

- Solution: Adopt the continuous droplet interface crossing encapsulation (cDICE) method. This technique has been optimized for high-yield and reproducible encapsulation of functional proteins, including complex mixtures of actin, bundling proteins, and motors, into cell-sized phospholipid vesicles [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Ring Formation Probability | Ineffective actin-membrane linkage | Implement biotin-neutravidin bridge with 1% biotinylated lipid and 4% biotinylated actin [13] |

| Uncontrolled Actin Gelation | Overly dense, highly cross-linked networks | Titrate down concentrations of bundling proteins (fascin, α-actinin); optimize actin monomer to cross-linker ratio [13] |

| No Contraction with Myosin | Poor force transmission from ring to membrane | Use talin/vinculin as a combined bundling and membrane-anchoring system [13] |

| Irreproducible Network Morphologies | Inconsistent encapsulation of protein components | Utilize cDICE encapsulation methods for higher reproducibility and precision [13] [8] |

| Bundle Curvature Doesn't Match Membrane | Incorrect choice of bundling protein | Replace fascin with α-actinin, VASP, or talin/vinculin for more flexible bundles [13] |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Reconstitution of Contractile Actomyosin Rings

This protocol outlines the methodology for forming membrane-bound actin rings and inducing their contraction within GUVs, based on the work of [13].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| G-Actin | Primary structural protein | Polymerizes into filamentous networks (F-Actin) [13] |

| Biotinylated G-Actin | Links filaments to the membrane | Recommend 4% of total actin; binds to neutravidin [13] |

| Biotinylated Lipids | Provides membrane anchor points | Recommend 1% of total lipid composition; binds neutravidin [13] |

| Neutravidin | Molecular bridge | Binds biotin on both actin and lipids, creating a secure link [13] |

| Bundling Proteins | Cross-links actin filaments | Fascin, α-actinin, VASP, or Talin/Vinculin combination [13] |

| Myosin II | Motor protein for force generation | ATP-dependent, drives contraction of the ring structure [13] |

| POPC Lipids | Forms vesicle membrane | Primary lipid for GUV formation [13] |

2. Encapsulation via cDICE

- Prepare the inner aqueous phase containing G-actin (with 4% biotinylated actin), your chosen bundling protein, neutravidin, and myosin in polymerization-compatible buffer.

- Form GUVs using the continuous droplet interface crossing encapsulation (cDICE) method with a lipid film containing POPC and 1% biotinylated lipids. This method ensures efficient co-encapsulation of all components within cell-sized vesicles [13].

3. Actin Polymerization and Ring Formation

- After encapsulation, allow actin to polymerize at room temperature. In the presence of bundling proteins and membrane anchors, the actin will self-organize.

- With membrane binding, the bundles will robustly condense into a single actin ring at the vesicle periphery, a process driven by energy minimization in spherical confinement [13].

4. Induction of Contraction

- Initiate contraction by providing an ATP-containing buffer.

- Upon ATP addition, myosin motors will generate force on the membrane-bound actin ring, leading to ring contraction and local constriction of the vesicle, forming furrow-like deformations [13].

Table 1: Efficacy of Different Actin Bundling Proteins in Ring Formation

| Bundling Protein | Mechanism of Actin Binding | Typical Bundle Morphology | Probability of Single Ring Formation (with membrane anchor) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fascin | Monomer with two actin-binding sites [13] | Straight, often kinked bundles [13] | Moderate |

| α-Actinin | Dimer that bridges two filaments [13] | Smoothly curved bundles [13] | High |

| Talin / Vinculin | Dimerize and require interaction to bundle [13] | Smoothly curved, membrane-proximal bundles [13] | Very High (Close to 100%) [13] |

| VASP | Tetramer linking up to four filaments [13] | Smoothly curved bundles [13] | High |

Table 2: Impact of Membrane Anchoring on Bundle Properties

| Experimental Condition | Primary Effect on Actin Bundles | Result on Large-Scale Organization |

|---|---|---|

| No Membrane Anchor | Bundles are straight; path is obstructed by membrane [13] | Disorganized clusters; multiple bundle orientations [13] |

| With Membrane Anchor | Bundles adopt the curvature of the membrane [13] | Condensation into a single, cohesive ring structure [13] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Reconstituting Contractile Actomyosin Rings

The Impact of Assembly Kinetics and Dynamic Arrest on Network Mechanics and Reproducibility

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My reconstituted actin networks show inconsistent architecture between experiments, even when using identical biochemical compositions. What could be causing this?

A1: Inconsistent architectures are likely due to variations in assembly kinetics, not your biochemical makeup. The final network morphology is a kinetically determined structure. If the kinetics of actin polymerization vary between experiments—affecting the time window during which filaments are mobile—the resulting architecture will differ. Bundle formation occurs only during a narrow time interval when the filament microenvironment is fluid; any factor altering the speed of polymerization or the onset of dynamic arrest will change the outcome [14] [15].

Q2: Why do I observe thick actin bundles at low F-actin concentrations but only fine meshworks at high concentrations, even with the same cross-linker concentration?

A2: This is a direct consequence of dynamic arrest. Bundle formation requires a fluid microenvironment that permits filament mobility. At high F-actin concentrations (typically above 1.0 µM), the high density of filaments leads to steric entanglements and cross-linking, arresting translational and rotational diffusion. This arrest prevents the alignment and bundling processes, favoring the formation of homogeneous meshworks instead [14].

Q3: How can I control the onset of dynamic arrest in my experiments to achieve a desired network structure?

A3: Control the onset of dynamic arrest by manipulating actin assembly kinetics. The onset of arrest coincides with the point where filament length exceeds the average filament spacing. You can influence this by:

- Controlling Nucleation Density: Using nucleators (e.g., formins, Arp2/3 complex) to adjust initial filament number and length [16].

- Varying Actin Concentration: A higher monomer concentration generally leads to longer filaments and faster dynamic arrest [14].

- Altering Cross-linking Speed: The rate at which cross-linkers are added or become active can shift the balance between bundling and arrest.

Q4: What are the best methods to spatiotemporally control actin polymerization in reconstituted systems to improve reproducibility?

A4: Several methods offer high reproducibility for spatial and temporal control:

- Micropatterning: Creates permanent, static "spots" of nucleation-promoting factors (NPFs) on a passivated surface to generate actin networks of defined shapes and locations [16].

- Protein Photoactivation: Uses light to transiently activate caged actin monomers or motor proteins, offering precise temporal control within a defined illumination area [16].

- Bead-based Reconstitution: Coating beads with NPFs and incubating them with a purified protein mixture leads to reproducible actin comet tail formation, providing a reliable readout of dynamics [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Failure to Form Actin Bundles

Issue: Experiments yield only fine meshworks or homogeneous networks instead of the expected bundled architecture.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly rapid dynamic arrest | Perform time-lapse imaging to monitor filament mobility. If the fluid phase is very short, bundling may be suppressed. | Reduce the actin monomer concentration or increase nucleator density to create shorter filaments, delaying entanglement [14]. |

| Insufficient cross-linker concentration | Titrate the cross-linker (e.g., α-actinin). Bundle formation follows mass action kinetics and requires a threshold concentration. | Systematically increase cross-linker concentration. For α-actinin, bundled networks typically require >1.0 µM [14]. |

| Filament concentration too high during mixing | When using pre-polymerized F-actin, ensure the final concentration after mixing is permissive for bundling (< 0.5 µM is highly bundled; > 1.0 µM is suppressed) [14]. | Dilute the F-actin stock before adding cross-linker to ensure the final concentration is in the bundling-permissive range. |

Problem: Poor Mechanical Reproducibility in Network Rheology

Issue: Measurements of network stiffness (shear modulus) or viscoelasticity show high variability between samples.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled assembly kinetics leading to different final architectures | Correlate the mechanical measurements with confocal microscopy of the network structure for the same sample. | Standardize the incubation time and temperature for polymerization across all experiments. Allow the network to fully assemble before mechanical testing [14]. |

| Variability in filament length distribution | Use TIRF microscopy to visualize and quantify filament lengths in different preparations [16]. | Use a consistent actin purification and polymerization protocol. Include a gel filtration or centrifugation step to remove aggregates before polymerization. |

Quantitative Data Reference

The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships from foundational studies, which should be used as a reference for diagnosing and troubleshooting experimental outcomes.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Actin Network Assembly with α-actinin

| Parameter | Experimental Condition | Observed Architectural Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-actinin Concentration | < 0.6 µM | Homogeneous meshwork of entangled filaments | [14] |

| 1.5 - 2.5 µM | Heterogeneous network (bundles embedded in meshwork) | [14] | |

| > 2.5 µM | Network comprised almost entirely of thick bundles | [14] | |

| F-actin Concentration | < 0.5 µM (with 0.6 µM α-actinin) | High density of bundles | [14] |

| > 1.0 µM (with 0.6 µM α-actinin) | Sharp decrease in bundling; fine meshwork | [14] | |

| Actin Polymerization State | 15% polymerized (0.75 µM F-actin) | Maximal rate of new bundle assembly | [14] |

| 40% polymerized (2.0 µM F-actin) | Cessation of new bundle formation | [14] | |

| MSD Scaling Exponent (δ) | δ ≈ 0.8 | Fluid-like microenvironment, permissive for bundling | [14] |

| δ decreases to 0.2 | Viscoelastic solid; dynamic arrest, bundling arrested | [14] |

Standardized Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Kinetics and Architecture

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for correlating actin assembly kinetics with final network architecture, which is critical for ensuring reproducibility.

Objective: To form F-actin networks cross-linked with α-actinin and simultaneously monitor polymerization kinetics, bundle formation, and microenvironment mechanics.

Materials:

- Monomeric (G-) actin (≥ 99% pure, avoid oligomers)

- Smooth muscle α-actinin

- Polymerization buffer (e.g., 1x KMEI: 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Imidazole pH 7.0)

- Fluorescent phalloidin (e.g., Acti-stain Phalloidin)

- Pyrene-labeled actin (for kinetic assays)

- Polystyrene tracer beads (1 µm diameter, for microrheology)

Method:

- Preparation: Clarify all protein solutions by high-speed centrifugation to preemptively remove aggregates. Keep G-actin on ice.

- Initiation: On ice, mix 5 µM G-actin with varying concentrations of α-actinin (e.g., 0.5 µM, 2.0 µM, 3.0 µM) in polymerization buffer. Include a catalytic amount of pyrene-actin (1-5%) and a dilute suspension of tracer beads.

- Kinetics Measurement: Transfer a portion of the mixture to a spectrofluorometer cuvette. Begin monitoring pyrene fluorescence (excitation 365 nm, emission 407 nm) at 25°C to track the polymerization time course.

- Imaging and Microrheology: Simultaneously, place a droplet of the reaction on a microscope slide and image immediately using time-lapse confocal microscopy.

- Acquire images of fluorescent phalloidin every 30 seconds for at least 60 minutes to visualize bundle formation.

- Acquire high-frame-rate videos (30 fps) of the tracer beads at 60-second intervals to calculate the Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) and the scaling exponent (δ).

- Quantification:

- From images, calculate the linear bundle density over time using a consistent intensity threshold.

- From bead videos, compute the MSD scaling exponent (δ) to quantify the fluid-to-solid transition of the microenvironment.

- Correlation: Overlay the time courses of actin polymerization (pyrene), bundle density, and MSD exponent to identify the critical window for bundle assembly.

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The diagram below illustrates the key decision points and relationships that govern the assembly of reconstituted actin networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal Reconstitution

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Role | Key Consideration for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Monomeric (G-) Actin | The fundamental building block for filament polymerization. | Use high-purity, lyophilized, or pre-clarified stocks. Consistency in source and purification is critical. |

| α-actinin | A classic actin cross-linking protein that can form both bundles and meshworks. | Concentration is a primary determinant of architecture. Titrate carefully for desired outcome [14]. |

| Fluorescent Phalloidin | A high-affinity stain for F-actin used for visualization. | Can stabilize filaments and alter dynamics. Use at minimal effective concentrations for live imaging. |

| Pyrene-labeled Actin | A fluorophore-labeled actin used to monitor polymerization kinetics in bulk assays. | The label can slightly alter polymerization kinetics. Use a low, consistent molar ratio (e.g., 5%). |

| Micropatterned Surfaces | Surfaces with defined geometry functionalized with nucleators to control spatial assembly. | Eliminates stochastic nucleation, dramatically improving architectural reproducibility [16]. |

| Nucleation Promoters (e.g., Formins, NPFs) | Proteins that control the rate and location of new filament formation. | Different nucleators produce filaments of different lengths and geometries, directly impacting network mechanics [16]. |

The reconstitution of cytoskeletal processes is a fundamental approach in bottom-up synthetic biology and mechanobiology, aiming to reconstruct complex cellular functions like division and motility from minimal components in vitro [8] [1] [17]. However, these assays are notoriously prone to variability and reproducibility challenges. A primary source of this inconsistency is biological context sensitivity—the profound influence that specific experimental conditions and cellular environments exert on assay outcomes. Unlike purely chemical reactions, cytoskeletal reconstitution involves dynamic, self-organizing systems whose final state is highly dependent on the precise context of their assembly [1]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to identify, troubleshoot, and control for these contextual variables, thereby enhancing the reliability of your cytoskeletal research.

FAQs: Understanding Core Concepts and Challenges

Q1: What is meant by "biological context sensitivity" in cytoskeletal assays?

Biological context sensitivity refers to the phenomenon where the outcome of a cytoskeletal reconstitution experiment is significantly influenced by specific, often subtle, parameters of the experimental environment. These are not simple "ingredients" but dynamic conditions. Key aspects include:

- Assembly Kinetics: The final structure and mechanical properties of a cytoskeletal network are highly dependent on the rates of filament formation, crosslinking, and bundling, which can trap the network in a non-equilibrium, metastable state [1].

- Molecular Crowding: The presence of macromolecular crowders like Ficoll 70 alters polymerization kinetics, filament persistence length, and the effective concentration of components, drastically impacting the resulting architecture [17].

- Membrane Composition: In vesicle-based reconstitutions, the charge and lipid composition of the membrane (e.g., inclusion of biotinylated or negatively charged lipids) are critical for proper protein binding and spatial patterning, such as with the MinDE system [17].

Q2: Why is my reconstituted actin network exhibiting different mechanical properties between experimental repeats?

This is a classic symptom of uncontrolled context sensitivity. The mechanics of biopolymer networks are not determined solely by their biochemical composition but are intensely sensitive to their formation history.

- Dynamic Arrest: Crosslinked networks like those formed by actin and α-actinin can become dynamically arrested before reaching equilibrium. The final network morphology and mechanics are therefore a snapshot of the kinetic competition between filament elongation and crosslinking at the moment of arrest [1].

- Competing Kinetics: The "race" between filament polymerization and bundling can lead to different structural and mechanical outcomes even with identical final concentrations of proteins [1]. Slight variations in temperature or mixing can thus lead to significant run-to-run variability.

Q3: How does spatial confinement impact cytoskeletal self-organization?

Spatial confinement in cell-sized volumes, such as inside Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs), is a major contextual factor that guides self-organization.

- Persistence Length vs. Container Size: The size of a confining environment relative to the persistence length of actin filaments influences the preferred architecture. For instance, flexible actin rings are more probable in smaller vesicles (diameter < 15 µm) as bundles assemble at the equator to minimize bending energy [17].

- Emergent Composite Behaviors: In networks with multiple filament types, steric interactions can lead to unexpected outcomes. For example, rapidly forming vimentin intermediate filaments can sterically hinder the crosslinking of slower-forming F-actin, resulting in a weaker composite network than either component alone would suggest [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low or No Actin Network Assembly in GUVs

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor actin polymerization inside GUVs | Suboptimal internal buffer conditions (salt, pH, ATP levels) for actin polymerization [8] [17]. | Systemically tune the internal buffer to simultaneously support actin (K+, Mg2+, ATP) and other co-encapsulated systems. Use a well-buffered system like 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with 1-2 mM MgCl2 and an ATP-regenerating system. |

| Inconsistent encapsulation | Inefficient loading of protein components during GUV formation [8]. | Utilize the double emulsion transfer method for more efficient and consistent encapsulation of macromolecules [17]. |

| Lack of membrane anchoring | Absence of specific lipids for protein binding. | Incorporate biotinylated lipids (e.g., DOPE-biotin) and neutravidin in the internal solution to link biotinylated actin filaments to the membrane [17]. |

Uncontrolled or Non-Reproducible Spatial Patterning

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Actomyosin bundles form clusters instead of equatorial rings | Lack of a spatial targeting system; bundles slip on the membrane [17]. | Co-encapsulate the bacterial MinDE protein system. MinDE oscillations can drive the diffusiophoretic transport of membrane-bound cargo (like actin) to the vesicle equator, enabling self-organized ring assembly [17]. |

| High variability in ring formation between GUVs | Inconsistent GUV size and internal composition. | Standardize GUV production parameters. Focus analysis on GUVs within a specific size range (e.g., 10-15 µm) where equatorial assembly is more probable [17]. Ensure consistent concentration of crowder (Ficoll 70) to stabilize patterns. |

Inconsistent Mechanical Readouts from Reconstituted Networks

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large variation in measured network stiffness | Uncontrolled assembly kinetics leading to different dynamically arrested states [1]. | Strictly control the timing and temperature of the polymerization and crosslinking steps. Pre-polymerize actin filaments before adding crosslinkers to separate the kinetics. |

| Unaccounted-for molecular motor activity. | If using myosin II, ensure ATP concentration is well-controlled and specified, as motor activity generates internal forces that dramatically alter network mechanics [1]. | |

| Network behavior deviates from theoretical models | Overlooking emergent behaviors in composite networks. | When reconstituting multi-filament systems, perform control experiments with individual components to baseline their properties. Be aware that steric interactions can dominate over biochemical ones [1]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Co-reconstitution of Actomyosin and MinDE Systems in GUVs for Spatial Patterning

This protocol enables the formation of spatially controlled, contractile actomyosin rings inside lipid vesicles, a key step towards synthetic cell division [17].

Key Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Steps:

Lipid Stock Preparation: Prepare a lipid stock solution in chloroform. A typical membrane composition for this assay includes:

- POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine): The primary phospholipid for membrane structure.

- DOPE-biotin (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(cap biotinyl)): A small percentage (0.5-1 mol%) to provide biotin handles for membrane anchoring.

- Negatively Charged Lipid (e.g., DOPG): A fraction (5-10 mol%) to facilitate MinD membrane binding and oscillation.

GUV Formation via Double Emulsion Transfer:

- Create a stable water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) double emulsion using microfluidic devices or gentle agitation.

- The inner aqueous phase contains the entire reaction mix to be encapsulated. The oil phase contains the dissolved lipids.

- Transfer the double emulsion across an oil-water interface to form the final GUVs in an external buffer.

Internal Solution Preparation: The inner aqueous phase must contain:

- Proteins: G-Actin (~5-10 µM), fascin (molar ratio 0.25-0.5 fascin/actin), myosin II, MinD, MinE.

- Energy and Ions: ATP (1-2 mM), MgCl₂ (1-2 mM).

- Crowding Agent: Ficoll 70 (1-2% w/v) to mimic cytoplasmic crowding and accelerate kinetics.

- Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with 50 mM KCl.

Incubation and Imaging:

- Allow the encapsulated system to incubate at room temperature or 25-30°C for several hours to allow for actin polymerization and MinDE pattern formation.

- Image using confocal or fluorescence microscopy.

- Phenotype Quantification: Systematically score the resulting actin architectures (soft webs, asters, flexible rings, stiff bundles) and their correlation with GUV size and the presence of Min proteins [17].

Protocol: Building a Mechanically Robust Crosslinked Actin Network

This protocol outlines the formation of a simple crosslinked F-actin network for mechanical testing, highlighting steps to ensure reproducibility.

Key Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Steps:

Pre-polymerization of Actin: First, polymerize G-Actin (e.g., 2-4 µM) in F-buffer (e.g., 2 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM CaCl₂, 1 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM KCl) for 1 hour at room temperature. This creates a consistent starting pool of filaments.

Controlled Crosslinking: Add the crosslinker (e.g., α-actinin at a molar ratio of 1:100 to 1:10 crosslinker:actin) to the pre-polymerized F-actin. Mix gently and thoroughly by pipetting. Note: The timing of this step is critical, as network evolution halts upon crosslinking [1].

Quiescent Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate without disturbance for a defined period (e.g., 30 minutes) at a controlled temperature. This allows the network to form and reach its dynamically arrested state.

Mechanical Testing: Load the sample into a rheometer or other mechanical testing device for characterization. Note that the network's strain-stiffening behavior is a product of its non-equilibrium structure [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cytoskeletal Reconstitution | Key Considerations for Robustness |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 [17] | Macromolecular crowder that mimics cytoplasmic conditions, accelerates actin polymerization, and alters MinDE oscillation dynamics. | Lot-to-lot consistency is critical. Concentration must be optimized and rigorously reported, as it directly impacts reaction kinetics and network morphology. |

| Biotinylated Lipids (e.g., DOPE-biotin) [17] | Provides anchor points in the membrane for neutravidin, which in turn binds biotinylated cytoskeletal proteins, linking the network to the membrane. | Maintain a low, consistent molar percentage (0.5-1%) in the lipid mixture. Avoid higher concentrations that might disrupt membrane fluidity or integrity. |

| Neutravidin [17] | A deglycosylated variant of avidin that forms a strong, stable bridge between biotinylated lipids on the membrane and biotinylated actin filaments. | Add from a fresh, single-use aliquot to a final concentration of ~0.1 µM. Multiple freeze-thaw cycles can reduce activity. |

| Fascin [17] | Actin-bundling protein that organizes individual actin filaments into higher-order, rigid bundles necessary for constructing ring scaffolds. | The fascin/actin molar ratio (e.g., 0.25 vs. 0.5) dictates bundle flexibility and final architecture (webs vs. rings vs. stiff bundles) and must be optimized and fixed [17]. |

| MinD / MinE Proteins [17] | A bacterial reaction-diffusion system that self-organizes on membranes. When reconstituted, it can provide spatial control for positioning membrane-bound cargo like actin rings. | Requires negatively charged membranes (e.g., with DOPG) and ATP. Oscillation patterns are sensitive to protein ratios, temperature, and crowder concentration. |

| Polydiacetylene (PDA) Fibrils [18] | A synthetic, polymerizable nanomaterial that can mimic a cytoskeleton, providing mechanical support and regulating membrane dynamics in synthetic cells. | Hydrophobicity can be tuned to position the fibrils either at the membrane lumen or in the internal lumen, dictating their functional role [18]. |

Advanced Protocols for Reproducible Cytoskeletal Network Assembly and Characterization

Engineering Tunable 3D Composite Actin-Microtubule Networks with Motor Proteins

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support resource is designed to help researchers overcome common challenges in reconstituting 3D composite cytoskeletal networks, directly supporting enhanced reproducibility in cytoskeletal reconstitution assays.

FAQ 1: My composite network collapses or fails to form a 3D structure. What could be wrong?

- Problem: The composite network lacks sufficient mechanical integrity or cross-linking.

- Solutions:

- Verify cross-linker concentration: Too few cross-linkers will not stabilize the network, while too many can make it too rigid and brittle. Perform a titration series.

- Check filament length: Short filaments may not form an interconnected network. Use high-speed centrifugation to remove short actin filaments and polymerize microtubules to a stable length.

- Confirm crowding agents: The presence of molecular crowders like Ficoll or dextran is often essential to mimic cellular conditions and promote network formation [18] [8]. A typical starting concentration is 2% w/v.

- Optimize ionic strength: Adjust the Mg²⁺ and K⁺ concentration in your buffer, as ions significantly affect filament bundling and cross-linker binding affinity.

FAQ 2: I am not observing the expected motor protein activity or cargo transport. How can I troubleshoot this?

- Problem: Motor proteins are inactive, or the network architecture hinders motility.

- Solutions:

- Validate motor protein activity: First, confirm motor function in a simple, single-filament gliding assay before moving to complex 3D networks.

- Ensure proper fuel levels: Maintain a constant ATP-regeneration system (e.g., Phosphocreatine and Creatine Phosphokinase) in your buffer to prevent ATP depletion during long experiments [19].

- Check network mesh size: A mesh size smaller than the motor protein itself can sterically hinder movement. If the network is too dense, dilute the actin/microtubule concentration. Reconstitution in cell-sized compartments can exacerbate issues with component availability, so efficient recycling of critical factors is essential [8].

- Confirm co-localization: Verify that your motor proteins are successfully binding to both filament types. Use fluorescently labeled motors to ensure they are present at actin-microtubule intersections.

FAQ 3: My network structure is highly variable between experiments, leading to poor reproducibility.

- Problem: Uncontrolled polymerization or inconsistent initial conditions.

- Solutions:

- Standardize protein quality: Use fresh or properly snap-frozen aliquots of proteins. Always perform a quality control check (e.g., SDS-PAGE, polymerization test) for each new batch.

- Control nucleation seeds: For microtubules, use stable seeds (e.g., GMPCPP-stabilized seeds) to initiate growth from a defined number of points. For actin, consider using nucleating proteins like formin or the Arp2/3 complex to control architecture.

- Pre-form filaments separately: Polymerize actin and microtubules separately under optimal conditions before gently mixing them for network assembly. This provides greater control over the initial state.

- Document buffer conditions meticulously: Small variations in pH, temperature, and reducing agents (like DTT) can drastically impact dynamics. Record all parameters.

Quantitative Parameters for Network Assembly

Table 1: Common Stock Solutions for Reconstitution Assays [19]

| Reagent | Typical Stock Concentration | Storage | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP (disodium salt hydrate) | 50 mM | -80°C | Energy source for motor proteins and actin polymerization |

| d-Glucose | 1 M (filtered) | -80°C | Component of oxygen-scavenging system |

| G-actin (unlabeled/labeled) | ≥ 48 µM | -80°C | Building block for actin filaments (F-actin) |

| Tubulin (unlabeled/labeled) | 5-10 mg/mL | -80°C | Building block for dynamic microtubules |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | 1-10 mM | -20°C | Stabilizes microtubules, suppresses dynamic instability |

Table 2: Ranges of Key Network Components for Tunable Properties

| Component | Typical Concentration Range | Effect of Increasing Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Actin | 1 - 10 µM | Increases network density, decreases mesh size. |

| Microtubules | 0.5 - 5 µM (tubulin) | Adds stiffness and compressive strength. |

| Cross-linker (e.g., Spectraplakin) | 10 - 100 nM | Increases network connectivity and viscoelasticity. |

| Molecular Crowder (e.g., Ficoll 70) | 0.5 - 3% w/v | Promotes volume exclusion, enhances polymerization, and compactness. |

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of Dynamic Microtubules with Pre-formed Actin Networks

This protocol is adapted from established methods for studying steric interactions between cytoskeletal filaments [20] [19].

Key Reagents & Function:

- G-actin: Monomeric actin, the building block for filaments.

- Tubulin: Heterodimeric protein that polymerizes to form microtubules.

- Paclitaxel (Taxol): Microtubule-stabilizing drug.

- ATP: Energy source for actin polymerization and motor proteins.

- BRB80 Buffer: Standard buffer for microtubule work (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8 with KOH).

Step-by-Step Method:

Flow Cell Preparation:

- Use thoroughly cleaned and functionalized glass coverslips. A common method is to incubate with a solution of 0.5 mg/mL biotin-BSA for 5-10 minutes, followed by a wash and incubation with 0.2 mg/mL NeutrAvidin.

- Assemble the flow cell with a spacer (e.g., double-sided tape) to create a chamber of ~10 µL volume.

Actin Network Assembly:

- Polymerize actin filaments separately by adding F-actin buffer to G-actin and incubating for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- To create specific actin architectures (e.g., bundled or isotropic networks), include cross-linkers like fascin during polymerization.

- Introduce the pre-formed F-actin network into the flow chamber and allow it to adsorb to the functionalized surface for 5-15 minutes.

Microtubule Polymerization & Introduction:

- Mix tubulin with a low ratio of fluorescently labeled tubulin in BRB80 buffer containing 1 mM GTP.

- Incubate the mixture on ice to prevent premature polymerization.

- Introduce the tubulin mix into the flow cell and transfer it to a heated chamber (typically 35-37°C) on the microscope stage to initiate microtubule polymerization within the actin network.

Imaging and Data Acquisition:

- Use TIRF or confocal microscopy to simultaneously image both networks using different fluorescence channels.

- Record time-lapse videos to monitor microtubule dynamic instability and its interaction with the actin network.

Workflow: Composite Network Reconstitution

Pathway: Motor Protein Interaction at Intersections

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Reconstitution

| Reagent / Material | Key Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biotinylated BSA & NeutrAvidin | Creates a functionalized surface in flow cells to anchor and organize filaments. | Essential for controlling network geometry and immobilization. |

| Stabilized Microtubule Seeds | Provides defined nucleation points for controlled microtubule growth. | Seeds polymerized with non-hydrolyzable GTP analogs (e.g., GMPCPP). |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Reduces photobleaching and radical damage during fluorescence imaging. | Commonly used: Glucose Oxidase, Catalase, and d-Glucose. |

| ATP-Regeneration System | Maintains constant ATP levels for sustained motor protein and actin dynamics. | Critical for long-term experiments; uses Phosphocreatine and Creatine Phosphokinase. |

| Engineered Cross-linkers | Mediates specific interactions between actin and microtubules. | e.g., purified Spectraplakin domains or synthetic cross-linkers. |

Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for cytoskeletal reconstitution in GUVs and droplets.

| Reagent Name | Function / Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Actin Proteins [16] | Primary structural filament network formation. | Ubiquitous eukaryotic protein; polymerizes into dynamic filaments; forms various architectures with binding proteins. |

| Nucleation-Promoting Factors (NPFs) [16] | Spatially control the initiation of actin polymerization. | Often coated on beads or patterns; activate complexes like Arp2/3 to generate branched actin networks. |

| Lipids for GUVs [16] [18] | Form the primary membrane structure of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. | Phospholipids self-assemble into a lipid bilayer, providing a biomimetic boundary. |

| Terpolymer Membrane [18] | Stabilize coacervate droplets or complex interfaces. | Forms a semi-permeable layer around coacervates, mimicking the cell membrane's barrier function. |

| Polydiacetylene (PDA) Fibrils [18] | Serve as an artificial, biomimetic cytoskeleton. | Nanometer-sized semi-flexible fibrils that form viscoelastic, entangled networks; can be functionalized. |

| Quaternized Amylose (Q-Am) [18] | Facilitate formation of crowded coacervate droplets and bundle anionic fibrils. | Positively charged polymer; used in coacervation and to aggregate negatively charged PDA fibrils via electrostatic interactions. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I achieve spatial control over actin network formation inside a confinement?

Answer: Achieving spatial control is crucial for mimicking cellular asymmetry. The main techniques involve patterning the activation sites for actin polymerization.

- Using Functionalized Beads: Coat microbeads with a Nucleation-Promoting Factor (NPF) and introduce them into your protein mixture. Actin comet tails will grow specifically from the bead surface, propelling it forward. This also provides a direct readout of actin dynamics [16].

- Employing Micropatterned Surfaces: Create defined "spots" of actin nucleation on a passivated surface using micropatterning. This technique localizes NPFs to generate branched actin networks of specific shapes and in controlled locations, either in 2D or 3D [16]. For membrane-proximal studies, this can be combined with lipid bilayers [16].

- Utilizing Protein Photoactivation: For transient and highly controllable activation, use photoactivatable actin monomers or motor proteins. The timing and the area of illumination define the activation, allowing for dynamic control over where the network forms [16].

FAQ 2: My encapsulated actin structures are unstable or fail to form. What are the critical parameters to check?

Answer: Instability often stems from issues with the internal environment or component availability. Focus on these parameters:

- Confirm Confinement Integrity: Ensure your GUVs or droplets are stable and do not rupture during the experiment. The membrane composition (e.g., lipid ratios, use of a stabilizing terpolymer) is critical for maintaining the encapsulated environment [18].

- Verify Component Activity and Concentration: The concentrations of actin, NPFs, and other actin-binding proteins must be optimized and verified to be active. Remember that in a confined space, the number of molecules is limited, and global depletion can significantly impact network dynamics and long-term maintenance [16].

- Mimic Cytosolic Crowding: The cell interior is highly crowded. Use crowding agents like dextran, Ficoll, or coacervates based on charged amylose derivatives (Q-Am/Cm-Am) to mimic this environment. Crowding affects diffusivity and biomolecular interactions, which is essential for proper actin network behavior [16] [18].

- Ensure Energy Availability: Actin dynamics are energy-dependent. Maintain an adequate concentration of ATP (or its regeneration system) in your buffer to fuel the polymerization and motor protein activity [16].

FAQ 3: How can I characterize the mechanical properties of the reconstituted cytoskeleton inside a confinement?

Answer: Traditional microscopy shows structure, but quantifying mechanics requires specialized techniques.

- Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D): This is a powerful technique to measure viscoelastic changes in reconstituted actomyosin systems in real-time. It detects changes in resonance frequency (Δf, related to mass) and energy dissipation (ΔD, related to rigidity/viscosity), allowing you to probe the network's response to perturbations like nucleotide state or binding proteins [6].

- Analysis of Bead Motility: When using NPF-coated beads, the movement itself is a readout of actin dynamics. You can quantitatively measure the speed, persistence, and size of the actin comet tail using fluorescence microscopy as indicators of network health and activity [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reconstitution of an Artificial Cytoskeleton in Membrane-Stabilized Coacervates

This protocol details the creation of a biomimetic cytoskeleton using polydiacetylene (PDA) fibrils inside a synthetic cell platform [18].

1. Preparation of PDA Fibrils:

- Design: Use diacetylene (DA) monomers with carboxylate end groups to enable electrostatic uptake and bundling. Mix with a small fraction (e.g., 10%) of DA monomers functionalized with azide or DBCO groups for post-assembly scaffolding.

- Polymerization: Irradiate the DA monomer solution with ultraviolet light (λ = 254 nm) for approximately 35 minutes. Monitor the polymerization by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy, where an increase in absorption in the visible spectrum (400–700 nm) indicates the formation of conjugated polymers. Verify fibril formation and dimensions using cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (cryo-TEM).

2. Formation of Coacervate Droplets:

- Mix an excess of positively charged Quaternized Amylose (Q-Am) with negatively charged Carboxymethylated Amylose (Cm-Am) to form coacervates via complex coacervation.

3. Integration of the Artificial Cytoskeleton:

- Add the pre-formed PDA fibrils to the coacervate mixture. The negatively charged carboxylate groups on the PDA will electrostatically interact with the positively charged Q-Am, leading to the bundling of nanometre-sized fibrils into micrometre-sized entangled networks observable via Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM).

- To stabilize the coacervates and control PDA localization, add a terpolymer that forms a semi-permeable membrane at the coacervate interface.

4. Controlling Cytoskeleton Localization:

- For a membrane-associated cytoskeleton, use PDA fibrils co-assembled from 90% carboxylate-terminated DA and 10% DBCO-functionalized DA. The hydrophobic DBCO moiety will drive association with the terpolymer membrane.

- For a luminal/cytoplasmic cytoskeleton, use PDA fibrils co-assembled from 90% carboxylate-terminated DA and 10% azide-functionalized DA. The more hydrophilic azide groups will keep the network distributed inside the coacervate lumen.

Protocol 2: Measuring Emergent Mechanics with QCM-D

This protocol uses QCM-D to detect viscoelastic changes in a reconstituted actomyosin bundle system [6].

1. Sensor Surface Preparation:

- Clean the QCM-D sensor crystals according to manufacturer protocols. Functionalize the sensor surface to promote the attachment of actin filaments or pre-formed bundles.

2. Baseline Establishment:

- Flow an appropriate buffer through the QCM-D chamber until stable baseline readings for both frequency (f) and dissipation (D) are achieved.

3. Sample Measurement:

- Introduce the reconstituted actomyosin bundle sample into the chamber.

- Monitor the changes in frequency (Δf) and dissipation (ΔD) in real-time. A decrease in Δf indicates mass accumulation on the sensor, while an increase in ΔD indicates the formation of a more dissipative (softer, more viscous) layer.

- To probe mechanical feedback, introduce perturbations such as:

- Different nucleotide states (e.g., ATP vs. ADP).

- Varying concentrations of actin-binding or crosslinking proteins.

- Changes in ionic strength to alter network stiffness.

4. Data Interpretation:

- Correlate the Δf and ΔD shifts with the biochemical perturbations. A stiffer, more elastic network will typically show a smaller increase in dissipation for a given frequency shift, while a softer, more viscous network will show a larger dissipation increase.

Data Presentation

Table 2: Quantitative analysis of color contrast for visualization elements, based on WCAG guidelines. This ensures diagrams are accessible and legible for all users [21] [22].

| Foreground Color | Background Color | Contrast Ratio | WCAG AA Rating (Text) | WCAG AAA Rating (Text) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #4285F4 (Blue) | #FFFFFF (White) | 4.5:1 | Pass (Large) | Fail |

| #EA4335 (Red) | #FFFFFF (White) | 4.2:1 | Pass (Large) | Fail |

| #FBBC05 (Yellow) | #202124 (Dark Gray) | 12.4:1 | Pass | Pass |

| #34A853 (Green) | #FFFFFF (White) | 3.2:1 | Fail | Fail |

| #5F6368 (Mid Gray) | #FFFFFF (White) | 6.3:1 | Pass | Pass |

| #202124 (Dark Gray) | #F1F3F4 (Light Gray) | 12.1:1 | Pass | Pass |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Workflow for GUV Reconstitution

Actin-Myosin Force Feedback Mechanism

Optimizing Co-organization of Multiple Filament Systems Through Cytolinkers and Crosslinkers

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when reconstituting multi-filament systems. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions to improve experimental reproducibility.

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Failed cytoskeletal co-localization | Incorrect stoichiometry of cytolinker to filament | Titrate cytolinker concentration; for anillin, use 5-50 nM as a starting range [23]. |

| Poor network formation in synthetic cells | Insufficient electrostatic driving force for bundling | Ensure presence of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (e.g., Q-Am for anionic PDA fibrils) [18]. |

| Unspecific aggregation | Cytolinker concentration too high, leading to nonspecific oligomerization | Optimize concentration; use mass photometry to confirm cytolinker is monomeric in solution prior to introduction [23]. |

| Lack of defined cytoskeletal positioning | Missing polarity/hydrophobicity cues in artificial cytoskeleton | Functionalize fibrils with terminal groups (e.g., 10% DBCO for membrane association, 10% azide for lumen distribution) [18]. |

| Inconsistent binding or crosslinking efficiency | Uncontrolled filament dynamics or incorrect nucleotide state | Use stable GTP-state microtubule seeds (GMPCPP) or taxol-stabilized microtubules for more reliable cytolinker binding [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using a reconstituted system to study cytolinkers like anillin?

Reconstituted systems allow for the precise study of specific cytolinker interactions without interference from the many other binding partners present in a cellular environment. This enables researchers to definitively establish direct binding capabilities, such as confirming that anillin can directly crosslink microtubules and actin filaments and mediate their sliding, independent of other cellular factors [23].

Q2: How can I control the spatial organization of an artificial cytoskeleton within a synthetic cell?

Spatial organization can be engineered by tuning the hydrophobicity of the cytoskeletal elements. For instance, polydiacetylene (PDA) fibrils functionalized with hydrophobic groups (like DBCO) will localize to the membrane of a coacervate-based synthetic cell. In contrast, fibrils with hydrophilic groups (like azide) will remain distributed throughout the internal lumen, allowing for the creation of distinct cytoskeletal architectures [18].

Q3: My cytolinker does not bundle filaments as expected. What should I check?

First, verify the presence of necessary co-factors. Some cytolinkers require the presence of a charged polymer to facilitate hierarchical assembly. For example, negatively charged PDA fibrils only form micron-sized bundles upon the addition of a positively charged polymer like Q-Am or poly(L-lysine). This bundling does not occur with neutral or negatively charged polymers [18]. Second, confirm the nucleotide state of your filaments, as some cytolinkers, like anillin, show a strong binding preference for GTP-state microtubules over GDP-state lattices [23].

Q4: What are the best practices for visualizing and quantifying interactions in these assays?

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy is a highly effective method for directly observing interactions such as diffusive binding, tip-tracking, and crosslinking in real-time [23]. To quantify encapsulation efficiency and spatial distribution within synthetic cell platforms, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) combined with line profile fluorescence measurements is recommended [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: In Vitro Reconstitution of Anillin-Mediated Microtubule-Actin Crosslinking

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating anillin's direct crosslinking function [23].

- Microscope Preparation: Passivate a glass coverslip flow chamber to prevent non-specific protein adhesion.

- Microtubule Assembly: Introduce tubulin along with stabilised GMPCPP microtubule seeds into the chamber and allow for dynamic microtubule growth.

- Filament Introduction: Introduce fluorescently labelled F-actin into the chamber.

- Initiate Crosslinking: Flow in a solution containing full-length human anillin (isoform 2, 5-50 nM) and image immediately using TIRF microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Quantify parameters such as binding frequency, diffusion coefficients, and the occurrence of actin filament sliding on microtubules.

Protocol 2: Integrating a Biomimetic Cytoskeleton into Synthetic Cells

This protocol outlines the creation of a functionalized artificial cytoskeleton inside membrane-stabilized coacervates [18].

- Fibril Polymerization: Synthesize polydiacetylene (PDA) fibrils by co-assembling diacetylene monomers (90% carboxylate-terminated, 10% azide- or DBCO-terminated) and polymerize them using UV light (254 nm) for ~35 minutes. Verify polymerization by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.

- Coacervate Formation: Form coacervate droplets by mixing a positively charged polymer and a negatively charged polymer.

- Cytoskeleton Integration: Incubate the pre-formed PDA fibrils with the positively charged polymer component to trigger bundle formation, then mix to form the coacervates. The fibrils will be efficiently taken up.

- Membrane Stabilization: Add a terpolymer to the coacervate solution to form a semi-permeable membrane at the interface.

- Validation: Use confocal microscopy to confirm the localization of the cytoskeleton (PDA-M at the membrane, PDA-L in the lumen).

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the featured experiments for cytoskeletal reconstitution.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Full-length human anillin (isoform 2) | Directly crosslinks microtubules and actin filaments; enables filament sliding and transport [23]. |

| Polydiacetylene (PDA) fibrils | Serves as a synthetic, biomimetic cytoskeleton; provides mechanical support and regulates membrane dynamics in synthetic cells [18]. |

| Carboxylate-terminated Diacetylene | Enables electrostatic uptake of fibrils into positively charged compartments and facilitates bundling via polyelectrolyte interactions [18]. |

| DBCO-functionalized Diacetylene | Provides hydrophobic handle for spatial control, localizing the artificial cytoskeleton to the synthetic cell membrane [18]. |

| Azide-functionalized Diacetylene | Provides hydrophilic handle for spatial control, maintaining the artificial cytoskeleton within the internal lumen of the synthetic cell [18]. |

| Quaternized Amylose (Q-Am) | Positively charged polyelectrolyte used in coacervate formation; also acts as a bundling agent for anionic PDA fibrils [18]. |

| GMPCPP-tubulin | Forms stabilized microtubule seeds for reconstitution assays; provides a preferred binding lattice for cytolinkers like anillin [23]. |

Experimental Workflow and Cytolinker Function

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow and mechanism of action for a key cytolinker.

Diagram 1: Core experimental workflow for in vitro reconstitution of cytolinker-mediated filament interactions.

Diagram 2: Anillin functions as a direct cytolinker, forming oligomers on microtubules to crosslink them with actin filaments [23].

Diagram 3: Controlling artificial cytoskeleton localization in synthetic cells by tuning fibril hydrophobicity [18].

Fluorescence Labeling Strategies for Multi-Spectral Visualization of Composite Dynamics

A robust and reproducible cytoskeletal reconstitution assay is foundational for research in cell mechanics, drug discovery, and synthetic biology. These assays allow researchers to dissect the complex behaviors of actomyosin networks, such as contraction and ring formation, in a controlled environment. Central to the success of these experiments is the effective use of multi-spectral fluorescence labeling, which enables the simultaneous visualization of multiple dynamic components—such as actin, myosin, cross-linkers, and membranes—within a synthetic cell. This technical support center is designed to help you overcome common challenges in labeling, thereby improving the reproducibility and quantitative output of your research. The following guides and protocols are framed within the context of advanced cytoskeletal reconstitution, drawing from cutting-edge methods in bottom-up synthetic biology [24] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions: Core Components for Reconstitution Assays

The table below details essential reagents for building and visualizing a minimal cytoskeletal system inside lipid vesicles or synthetic compartments.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Cytoskeletal Reconstitution and Visualization

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in the Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin & Associated Proteins | G-actin, Fascin, α-Actinin, Talin/Vinculin complex, VASP | Forms the primary filamentous network; cross-linkers dictate bundle architecture (e.g., straight vs. curved bundles) [24]. | Protein purity and activity are critical. Different bundlers create structurally distinct networks. |

| Membrane Anchor System | Biotinylated lipids, Biotinylated G-actin, Neutravidin | Links the actin cytoskeleton to the lipid membrane via a high-affinity biotin-neutravidin bridge, promoting ring assembly [24]. | Optimal concentrations (e.g., 1% biotinylated lipid, 4% biotinylated actin) are key for efficient binding without disrupting polymerization. |

| Motor Proteins | Myosin II (or similar) | Generates contractile forces on actin networks, leading to ring constriction and membrane deformation [24]. | ATP concentration must be optimized to drive motor activity. |

| Fluorescent Labels | SiR-Actin/Tubulin kits, Fluorogenic HaloTag/SNAP-tag substrates (e.g., JF525, JF669), Self-labeling tags (HaloTag, SNAP-tag) | Enable specific, high-contrast visualization of target proteins. Fluorogenic probes remain dark until bound, minimizing background [25] [26]. | Match the fluorophore's photostability and wavelength to your microscopy modality (e.g., STED, live-cell tracking). |

| Encapsulation Machinery | Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs), cDICE apparatus | Provides cell-sized spherical confinement for reconstituting cytoskeletal processes [24]. | Encapsulation efficiency is a major variable; cDICE improves reproducibility. |

Experimental Protocols: Core Methodologies for Reproducible Assays

Protocol: Reconstitution of a Contractile Actomyosin Ring in GUVs

This protocol is adapted from advanced bottom-up synthetic biology approaches for studying division machinery [24].

Key Materials:

- G-actin (from commercial source, stored in G-buffer)

- Actin bundling protein (e.g., Fascin, α-Actinin, or Talin/Vinculin)

- Biotinylated G-actin (typically 4% of total actin)

- Neutravidin

- Myosin motors (e.g., Myosin II)

- Lipids: POPC with 1% biotinylated lipid

- cDICE apparatus for encapsulation

Step-by-Step Method:

- Vesicle Formation: Form Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) from a lipid mixture of POPC and 1% biotinylated lipid using the cDICE method. This method efficiently encapsulates large biomolecules like proteins.

- Sample Preparation: In parallel, prepare the internal reaction mix containing:

- G-actin (with 4% biotinylated actin)

- Selected actin bundling protein

- Neutravidin (to bridge biotinylated actin and lipids)

- ATP and polymerization buffer components

- Encapsulation: Use the cDICE method to encapsulate the reaction mix from Step 2 within the GUVs from Step 1. The precise composition of the initial mix is crucial, as components cannot be added later.

- Polymerization and Assembly: Allow the encapsulated actin to polymerize. The combination of confinement, cross-linking, and membrane binding will promote the condensation of actin into a single ring-like structure at the vesicle membrane.

- Induction of Contraction: For contractility assays, include myosin motors in the initial reaction mix. Upon addition of ATP to the external solution (or if encapsulated), the motors will generate force, leading to the contraction of the actin ring and deformation of the vesicle.

Protocol: Multi-Spectral Labeling with Chemogenetic FRET Pairs

For multiplexed imaging of dynamics, chemogenetic FRET biosensors offer large dynamic ranges and spectral tunability [27].

Key Materials:

- ChemoG5 (or other ChemoX variants) plasmid DNA

- Cell-permeable rhodamine-based fluorophore (e.g., SiR, JF552, TMR)

- Standard cell culture and transfection reagents

Step-by-Step Method:

- Genetic Encoding: Fuse the gene of interest to the optimized chemogenetic FRET construct (e.g., ChemoG5) and express it in your cellular or synthetic cell system.

- Fluorophore Labeling: Incubate the cells/vesicles with a cell-permeable substrate for the HaloTag (e.g., SiR). The fluorophore covalently binds to the HaloTag domain.