Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cytoskeleton's dynamic role as a central regulator of cellular behavior, bridging fundamental biology with clinical applications.

Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cytoskeleton's dynamic role as a central regulator of cellular behavior, bridging fundamental biology with clinical applications. We explore the core molecular mechanisms governing actin, microtubule, and intermediate filament dynamics, and detail advanced methodologies for their study in physiological and pathological contexts. The content addresses critical challenges in targeting cytoskeletal pathways, including heterogeneous drug responses in cancer subtypes and cytoskeletal defects in neurodegenerative diseases. By integrating foundational knowledge with emerging technical approaches and validation strategies, this review serves as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and manipulate cytoskeletal dynamics for therapeutic benefit in oncology, neurology, and regenerative medicine.

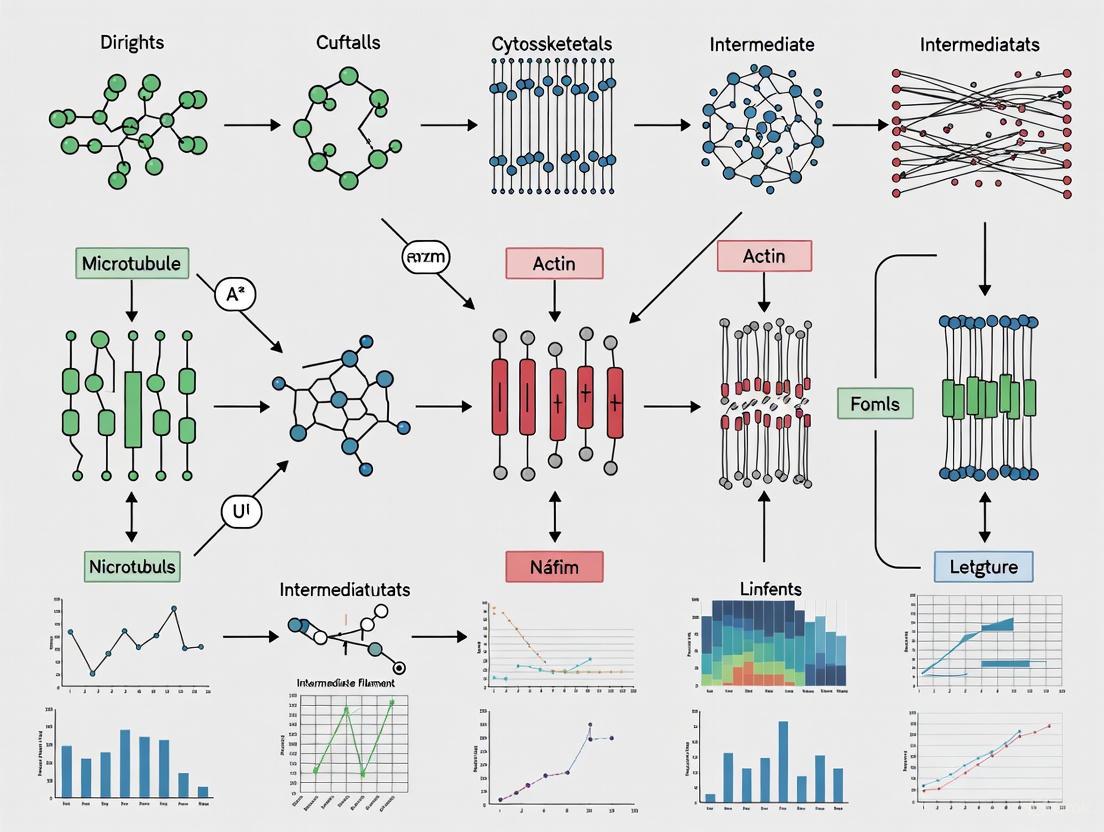

The Dynamic Cytoskeleton: Architectural Principles and Regulatory Mechanisms

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic and intricate network of protein filaments, provides the fundamental structural and functional framework for all eukaryotic cells. Comprising three core components—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—this system determines cellular shape, enables mechanical resistance, facilitates intracellular transport, and powers cell motility [1]. Beyond these structural roles, the cytoskeleton is increasingly recognized as a central signaling node that integrates mechanical and biochemical cues to regulate virtually all aspects of cellular behavior, from division and differentiation to disease progression [2]. In specialized tissues, cytoskeletal components enable critical functions: keratin intermediate filaments provide mechanical integrity to epithelial cells, neurofilaments support the elaborate architecture of neurons, and the coordinated action of actin and myosin filaments enables muscle contraction [3] [1]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these three core cytoskeletal systems, their dynamic interplay, and their collective role in cellular mechanobiology, with particular emphasis on contemporary research methodologies and quantitative biophysical properties relevant to drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Structural and Functional Characteristics

Each cytoskeletal filament type possesses distinct biochemical composition, structural organization, and mechanical properties that define its unique functional contributions to cellular physiology. The table below provides a comprehensive quantitative comparison of these core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Structural and Functional Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

| Parameter | Actin Filaments (Microfilaments) | Microtubules | Intermediate Filaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~7 nm [4] [1] | ~25 nm [4] [1] | ~10 nm [4] [1] |

| Protein Subunit | Actin (G-actin) [1] | α/β-Tubulin heterodimer [5] [1] | Tissue-specific (e.g., Keratin, Vimentin, Lamin) [3] [1] |

| Structure | Two intertwined helical strands (F-actin) [1] | Hollow cylinder of 13 protofilaments [1] | Rope-like, staggered tetramers [3] |

| Polarity | Yes (Barbed/+ and Pointed/- ends) [2] | Yes (Plus/+ and Minus/- ends) [5] | No (Non-polar) [6] |

| ATP/GTP Hydrolysis | ATP [2] | GTP [5] | Not required for assembly [3] |

| Primary Mechanical Role | Tension bearing [1] | Compression resisting [1] | Tensile strength, mechanical stability [5] [1] |

| Dynamic Instability | Yes [3] | Yes [3] | No (more stable) [3] |

The mechanical synergy between these systems is critical for cellular integrity. Actin filaments form a cortical network beneath the plasma membrane that resists tensile forces, while microtubules function as intracellular struts that counteract compressive loads [1]. Intermediate filaments, with their rope-like architecture and exceptional extensibility, provide tensile strength and enhance the cell's ability to withstand large deformations without mechanical failure [6] [1]. This composite material design allows the cytoskeleton to be both strong and resilient, adapting to a wide range of mechanical challenges.

Cytoskeletal Dynamics and Mechanotransduction

Force Generation and Cellular Mechanics

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic structure that continuously remodels in response to intracellular and extracellular signals. Actin filaments generate contractile forces through their association with myosin motor proteins, forming actomyosin complexes that power cell migration, cytokinesis, and changes in cell shape [1] [2]. These force-generating capabilities are particularly evident in stress fibers—contractile bundles of F-actin and myosin II that are connected to focal adhesions and play a crucial role in mechanotransduction [2]. Microtubules exhibit dynamic instability, stochastically switching between growth and shrinkage phases, which allows them to rapidly reorganize the intracellular space and respond to cellular demands [5] [6]. This dynamic behavior is crucial for mitotic spindle formation during cell division and the intracellular positioning of organelles [5].

Integrated Mechanosensing and Signaling

The cytoskeleton serves as a primary mechanotransduction pathway, translating mechanical forces into biochemical signals that regulate gene expression and cell fate [2]. Mechanical stresses are sensed at focal adhesions and transmitted through the cytoskeletal network to the nucleus, influencing nuclear shape, chromatin organization, and tension-dependent signaling pathways such as YAP/TAZ (Yes-associated protein/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif) [2]. The perinuclear actin cap, a highly organized network of actomyosin bundles that connects to the nucleus via LINC complexes, plays a particularly important role in this process by physically transducing forces from the extracellular matrix to the nuclear envelope [2]. Recent research has revealed that cytoskeletal proteins, including actin and myosin, also function within the nucleus, where they directly influence transcription by interacting with RNA polymerases and chromatin remodeling complexes [2].

Diagram: Cytoskeletal Mechanotransduction Pathway

The diagram above illustrates the integrated mechanotransduction pathway where external mechanical forces are sensed at focal adhesions, transmitted through cytoskeletal networks, and ultimately influence nuclear signaling and cell fate decisions through effectors like YAP/TAZ.

Experimental Methodologies for Cytoskeletal Research

Traction Force Microscopy and Cytoskeletal Disruption

To investigate the mechanical contributions of specific cytoskeletal components, researchers employ targeted disruption approaches combined with quantitative biomechanical measurements. A representative protocol from a glaucoma study illustrates this methodology [7]:

Objective: To quantify the relative contributions of actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments to cellular traction force generation and collagen matrix remodeling in human trabecular meshwork cells.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Culture normal human high-flow TM cells on compliant type I collagen gels (4.7 kPa stiffness, confirmed by atomic force microscopy) to mimic physiological conditions [7].

- Cytoskeletal Disruption:

- Actin disruption: Treat cells with Latrunculin B (0.5 µM for 4 hours) to depolymerize actin filaments [7].

- Microtubule disruption: Treat cells with Nocodazole (10 µM for 4 hours) to depolymerize microtubules [7].

- Intermediate filament disruption: Treat cells with Acrylamide (5 mM for 4 hours) to disrupt vimentin intermediate filaments [7].

- Force Measurement: Quantify cell-generated traction forces using traction force microscopy, which measures the displacement of fluorescent beads embedded in the collagen substrate [7].

- Collagen Reorganization Assessment: Analyze collagen fibril orientation and strain using quantitative image analysis of second harmonic generation or confocal reflection microscopy [7].

Key Findings: This approach revealed that disruption of actin filaments or microtubules reduced cellular traction forces by approximately 80% (∼10 kPa) and decreased local collagen fibril strain by ∼3.7 arbitrary units. In contrast, intermediate filament disruption produced only modest, non-significant changes, indicating a hierarchical mechanical contribution where actin and microtubules work synergistically as the primary force-transmitting systems [7].

Advanced Imaging and Simulation Approaches

Advanced microscopy techniques are essential for visualizing cytoskeletal dynamics and organization:

Super-resolution Microscopy: MoNaLISA (Molecular Nanoscale Live Imaging with Sectioning Ability) enables time-lapse imaging of whole cells with approximately 50 nm resolution and reduced photodamage. This technique allows tracking of single vimentin intermediate filament dynamics with nanometer precision, revealing distinct mechanical behaviors between perinuclear and peripheral filament pools [8].

Quadruple Optical Trap Experiments: This approach quantitatively characterizes filament-filament interactions. Two filaments are held with four optical traps, brought into perpendicular contact, and moved relative to each other while measuring interaction forces. When combined with simulations parametrized using Cytosim software, this method can determine the kinetic parameters of bonds between cytoskeletal filaments, such as those between vimentin intermediate filaments and microtubules [9].

Diagram: Quadruple Optical Trap Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal Studies

The table below catalogizes essential research reagents and their applications in cytoskeletal research, with a focus on pharmacological agents used to perturb specific filament systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Cytoskeletal Manipulation

| Reagent | Target | Mechanism of Action | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latrunculin B | Actin filaments | Binds G-actin, prevents polymerization [7] | Depolymerizes actin to assess its mechanical role [7] |

| Nocodazole | Microtubules | Binds β-tubulin, disrupts polymerization [7] | Depolymerizes microtubules to study force transmission [7] |

| Acrylamide | Vimentin IFs | Disrupts intermediate filament organization [7] | Tests intermediate filament contribution to mechanics [7] |

| Rho/ROCK inhibitors | Actomyosin signaling | Inhibits Rho-associated protein kinase | Reduces cellular contractility; studies mechanotransduction [2] |

| Fluorescent tubulin (GFP-tubulin) | Microtubules | Labels microtubules for live imaging | Visualizes microtubule dynamics and organization [8] |

| Vimentin-rsEGFP2 | Intermediate filaments | Photoactivatable label for super-resolution | Tracks single IF dynamics with MoNaLISA nanoscopy [8] |

| EMTB-3xGFP | Microtubules | Microtubule-binding domain fusion tag | Visualizes microtubules with high signal-to-noise [8] |

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Dysregulation of cytoskeletal components contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis, making them attractive therapeutic targets. In glaucoma, pathological stiffening of the trabecular meshwork results from aberrant cytoskeletal dynamics, with actin-microtubule synergy dominating force transmission and collagen strain regulation [7]. Glaucomatous cells in low-flow regions exert exceptionally strong traction forces leading to local extracellular matrix stiffening, which impedes aqueous humor outflow and increases intraocular pressure [7]. Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also involve cytoskeletal pathologies, with tau protein malfunctions affecting microtubule stability in Alzheimer's and compromised microtubule assembly contributing to neuronal degradation in Parkinson's [1]. In cancer biology, vimentin expression serves as a biomarker for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and increased metastatic potential [8], while disruptions to the perinuclear actin cap correlate with nuclear shape abnormalities and impaired cell motility in cancer cells [2]. These clinical connections highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting cytoskeletal dynamics, with current research exploring cytoskeletal-directed agents for conditions ranging from glaucoma to metastatic cancer.

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of protein filaments, is fundamental to cellular architecture, mechanical integrity, and behavior. Its functional versatility is governed by a sophisticated suite of molecular regulators that control filament assembly, disassembly, and mechanical output. These regulators—actin-binding proteins (ABPs), microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), and motor proteins—translate biochemical signals into precise structural changes and forces that direct processes ranging from cell division and migration to intracellular transport and signal transduction. In research and therapeutic contexts, understanding these regulators provides critical insights into disease mechanisms, including cancer metastasis, neurodegenerative disorders, and cellular reprogramming. This guide synthesizes current knowledge on the structure, function, and experimental analysis of these molecular machines, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals exploring cytoskeletal dynamics and its applications in biomedicine.

Actin-Binding Proteins (ABPs)

Classification and Molecular Functions

Actin-binding proteins are a diverse class of regulators that control the assembly, organization, and disassembly of actin filaments (F-actin). They function through specific, often regulated, interactions with actin monomers (G-actin) or filaments to orchestrate the dynamic remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, which is essential for cell motility, shape changes, and mechanical signaling [2] [10].

Table 1: Major Classes of Actin-Binding Proteins and Their Functions

| Class | Representative Proteins | Core Function | Effect on Actin Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Promoters | Arp2/3 complex, Formins (e.g., VASP) | Initiate new filament formation | Promotes polymerization; Arp2/3 creates branched networks, formins create unbundled filaments [2] |

| Severing/Depolymerizing | ADF/Cofilin, Gelsolin | Break filaments or promote disassembly | Increases filament turnover and monomer recycling [2] [11] |

| Capping | CP, Tropomodulin | Bind filament ends | Prevents addition/loss of subunits, stabilizing filament length [2] |

| Cross-Linking | α-Actinin, Fascin | Connect filaments to each other | Forms bundles and networks, increasing structural integrity [2] |

| Monomer Binding | Profilin, Twinfilin | Bind G-actin | Regulates monomer pool available for polymerization [10] [11] |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Signaling Inputs

The activity of ABPs is under intricate biochemical control. A primary regulatory mechanism involves phosphoinositide (PIPn) signaling, particularly through PtdIns(4,5)P2 (PIP2) at the plasma membrane. This lipid acts as a central hub to control ABP activity, thereby linking extracellular signals to cytoskeletal reorganization [11].

- Inhibition of Disassembly: PtdIns(4,5)P2 sequesters proteins like cofilin and gelsolin, preventing their interaction with actin filaments. This inhibition stabilizes the actin network. Upon PIP2 hydrolysis, these proteins are released, leading to enhanced filament severing and disassembly [11].

- Regulation of Polymerization: Profilin, which promotes the exchange of ADP for ATP on G-actin and facilitates actin addition to barbed ends, is also regulated by PtdIns(4,5)P2. Their interaction can release profilin from actin, making monomers available for polymerization in response to specific signals [11].

The diagram below illustrates how external signals trigger PIPn-mediated regulation of ABPs to control actin network architecture.

Experimental Analysis of ABPs

Studying ABP function requires a combination of biochemical, biophysical, and cell-based assays. Key Methodology: In Vitro Actin Polymerization Assay (Pyrene-Actin Assay) This foundational assay quantitatively measures the kinetics of actin filament assembly in real-time.

- Principle: Actin monomers are conjugated with pyrene, a fluorophore whose fluorescence increases dramatically upon incorporation into a filament. The rise in fluorescence over time directly reports on the rate of polymerization [10].

- Protocol:

- Protein Purification: Purify G-actin from muscle acetone powder or recombinant sources using cycles of polymerization/depolymerization and gel filtration. ABPs are expressed recombinantly and purified via affinity chromatography [10].

- Sample Preparation: In a low-salt buffer (to prevent spontaneous nucleation), mix pyrene-labeled G-actin (typically 5-10% of total actin) with unlabeled G-actin. Add the ABP of interest (e.g., profilin, cofilin) at varying concentrations.

- Initiation: Rapidly initiate polymerization by adding salt (KCl or MgClâ‚‚ to 50-100 mM) and ATP (1 mM) to the mixture.

- Data Acquisition: Immediately transfer the solution to a cuvette and monitor fluorescence (excitation ~365 nm, emission ~407 nm) in a fluorometer over 30-60 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. time. Compare parameters like nucleation lag time, initial polymerization rate, and final steady-state level between conditions to determine the ABP's effect.

- Applications: This assay can distinguish between nucleators, cappers, severing proteins, and monomer sequesterers based on their characteristic effects on the polymerization curve.

Microtubule-Associated Proteins (MAPs)

Structural and Regulatory MAPs

Microtubule-associated proteins encompass a broad category of proteins that bind to microtubules to regulate their stability, organization, and interactions with other cellular components. They are broadly classified into Structural MAPs, which stabilize and bundle microtubules, and Regulatory MAPs, which control the dynamic instability of microtubules (growing and shrinking phases) [12].

- Stabilizers and Destabilizers: Proteins like Tau and certain MAP4 isoforms stabilize microtubules, while others like stathmin/Op18 promote depolymerization. The balance between these opposing forces is critical for cellular processes like mitosis and neuronal axon guidance.

- Dysfunction in Disease: Aberrations in MAP expression and function are strongly linked to disease. For example, in breast cancer, alterations in MAPs such as the loss of the tumor suppressor ATIP3 or overexpression of the oncogene MASTL contribute to metastatic potential and therapy resistance by deregulating microtubule assembly and stability [12].

MAPs in Signaling Pathways

MAPs are integral components of major signaling cascades that sense and respond to the cellular environment. The Hippo pathway, a key regulator of organ size and cell fate, is one such pathway where MAP4K family members act as upstream regulators.

Table 2: MAP4K Family Members in Cellular Signaling and Disease

| Kinase | Alternative Name | Key Roles in Signaling | Implication in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAP4K1 | HPK1 | Negative regulator of T-cell receptor signaling; activates JNK and Hippo pathways [13] | Overexpression in AML confers drug resistance; targeted to boost immunotherapy [13] |

| MAP4K4 | HGK | Regulates actin cytoskeleton via STRIPAK complex; JNK and Hippo pathway activation [13] | Promotes tumor invasion and metastasis |

| MAP4K7 | TNIK | Activator of JNK and Hippo pathways [13] | Emerging target in colorectal cancer |

The following diagram integrates MAP4K proteins into the Hippo signaling cascade, demonstrating how they influence cell proliferation and fate.

Experimental Analysis of MAPs

Key Methodology: Microtubule Co-Sedimentation Assay This assay is used to confirm and quantify the direct binding of a MAP to microtubules in vitro.

- Principle: Microtubules are heavy and can be pelleted by high-speed centrifugation. If a MAP binds to microtubules, it will co-sediment with the pellet; otherwise, it will remain in the supernatant.

- Protocol:

- Polymerize Microtubules: Purify tubulin and polymerize it into microtubules in the presence of GTP and a stabilizing agent (e.g., paclitaxel/Taxol).

- Incubation: Incubate the purified MAP with pre-formed microtubules in a suitable binding buffer (e.g., containing BRB80 buffer: 80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifugation: Ultracentrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 100,000 x g for 30 minutes at 25°C) to pellet the microtubules and any bound protein.

- Analysis: Carefully separate the supernatant (unbound protein) from the pellet (bound protein). Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining or immunoblotting. The amount of MAP in the pellet fraction indicates binding affinity.

Motor Proteins

Kinesins and Dyneins: Structure and Function

Motor proteins are molecular machines that convert chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis into mechanical movement along cytoskeletal tracks. They are essential for intracellular transport, cell division, and signal transduction.

- Kinesins: Most kinesins move toward the plus-end of microtubules. They typically have a homodimeric structure with two motor domains (heads) that processively "walk" along the microtubule. Kinesin-1, the founding member, transports various cargos, including vesicles, organelles, and proteins, from the cell center toward the periphery [14].

- Dyneins: Dyneins are large multi-subunit complexes that move toward the minus-end of microtubules, transporting cargo towards the cell center. They are crucial for mitosis, organelle positioning, and the retrograde transport of signals in neurons.

A recent landmark study on kinesin-2 revealed a previously unknown "hook-like adaptor and cargo-binding (HAC) domain" in its tail. This HAC domain, with a helix–β-hairpin–helix (H-βh-H) motif, acts as a molecular connector, enabling the motor to specifically recognize and bind its cargo, the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein, via adaptor protein KAP3 [15]. This discovery provides the first atomic-level insight into the "logistics code" of cellular transport.

Controversies and Mechanistic Insights

Decades of research on motor proteins like kinesin-1 have yielded a detailed but sometimes conflicting understanding of their dynamics. The table below summarizes key contrasting experimental findings.

Table 3: Contrasting Experimental Observations on Kinesin-1 Dynamics

| Aspect of Dynamics | Conflicting Observation A | Conflicting Observation B | Potential Explanatory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP Binding State | Binding occurs in the one-head-bound (1HB) state [14] | Binding occurs mainly in the two-heads-bound (2HB) state [14] | Different attachment points and sizes of labels may impede motor head movement. |

| Velocity vs. Load | Velocity has a sigmoid relationship with backward load (movable optical trap) [14] | Velocity has a nearly linear relationship with backward load (fixed optical trap) [14] | Fixed traps create a load that increases as the motor moves, while movable traps maintain constant load. |

Experimental Analysis of Motor Proteins

Key Methodology: Single-Molecule Optical Trapping This powerful technique allows researchers to observe and manipulate the mechanical steps of individual motor proteins in real-time.

- Principle: A dielectric bead (e.g., polystyrene or silica) is attached to a single motor protein. This bead is caught in the focus of a highly focused laser beam (optical trap), which acts like a spring, exerting a force on the bead. As the motor protein steps along its track, it displaces the bead, and this displacement is measured with nanometer precision, allowing the measurement of step size, velocity, and stall force [14].

- Protocol:

- Surface Preparation: Create a flow chamber with a glass surface. Anchor microtubules to the surface, often via biotin-neutravidin linkages.

- Motor Protein Labeling: Engineer the motor protein (e.g., kinesin) to have a specific tag (e.g., His-tag or biotin ligase site) on its tail domain. Bind the motor to a bead coated with the appropriate binding partner (e.g., anti-His antibody or streptavidin).

- Assay Setup: Flow the bead-motor complexes into the chamber in an ATP-containing motility buffer. Use a microscope to position a bead over a surface-bound microtubule.

- Data Acquisition: Once a motor engages the microtubule, it will begin to walk, pulling the bead from the center of the optical trap. Record the bead's position with a quadrant photodiode detector at high temporal resolution (kHz range).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the recorded trajectory to extract parameters like step size (typically ~8 nm for kinesin), velocity (up to ~800 nm/s), and stall force (the load at which forward and backward steps are equally probable, ~6-8 pN for kinesin) [14].

- Variants: Fixed traps measure force as the motor moves away from the trap center, while feedback-controlled movable traps maintain constant force on the motor, explaining some of the conflicting data observed in velocity-load relationships [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cytoskeletal Research

| Reagent/Tool | Key Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Actin from Muscle | High-quality substrate for in vitro polymerization and binding assays. | Pyrene-actin polymerization assays to study ABP activity [10]. |

| Tubulin & Microtubule Stabilizers (e.g., Taxol/Paclitaxel) | Essential for polymerizing and stabilizing microtubules for structural and binding studies. | Microtubule co-sedimentation assays to test MAP binding [12]. |

| Caged/Photoactivatable Compounds | Enable precise spatiotemporal control of cytoskeletal dynamics using light. | Uncoupling the timing of signal induction (e.g., ATP or Ca²⺠release) in live cells. |

| Single-Molecule Labeling (e.g., Gold Nanoparticles, Fluorophores) | High-resolution tracking of molecular movement. | Visualizing the stepping dynamics of single kinesin molecules on microtubules [14]. |

| Cytoskeletal-Targeted Inhibitors | Chemically perturb specific regulators to determine function. | Using ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to study actomyosin contractility in cell reprogramming [2]. |

| Recombinant ABPs/MAPs/Motors | Defined, consistent protein for mechanistic in vitro studies. | ATPase assays with purified kinesin to understand chemomechanical coupling. |

| Rapamycin-d3 | Rapamycin-d3, MF:C51H79NO13, MW:917.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Linoleoyl Glycerol | 1-Linoleoyl Glycerol, MF:C21H38O4, MW:354.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Perspectives on Therapeutic Targeting

The molecular regulators of the cytoskeleton are not merely fundamental to cell biology; they represent a promising frontier for therapeutic intervention. The critical role of cytoskeletal dynamics in cancer progression is underscored by the ability of tumor cells to alter ABP, MAP, and motor protein activity to drive invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance [12]. For instance, targeting specific cytoskeletal regulators like PAK kinases, FAK, or MAP4K family members is being explored as a strategy to mitigate metastasis and overcome resistance in aggressive breast cancer subtypes [12] [13].

Furthermore, in the field of regenerative medicine, manipulating the cytoskeleton through biophysical or biochemical cues—such as modulating substrate stiffness or using ROCK inhibitors—has been shown to enhance the efficiency of cellular reprogramming and direct stem cell fate decisions [2] [16]. This highlights the profound influence of these molecular regulators on cellular identity and function. Future research and drug development will continue to decode the intricate logistics of cytoskeletal regulation, leveraging advanced structural techniques like cryo-EM [15] and single-molecule biophysics to design highly specific inhibitors and novel therapeutic strategies for a wide range of human diseases.

The interface between the plasma membrane and the cytoskeleton constitutes a critical signaling hub where cells perceive, integrate, and respond to extracellular cues. This dynamic boundary facilitates the transduction of mechanical and biochemical signals into intracellular responses that govern complex cell behaviors including migration, polarization, and division. This technical review examines the molecular machinery and regulatory mechanisms operating at this interface, with emphasis on phosphoinositide signaling, small GTPase regulation, and mechanotransduction pathways. We synthesize current understanding of how cytoskeletal components—actin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—interface with membrane-associated signaling networks to coordinate cellular responses. The clinical implications of these processes in cancer metastasis, immune function, and developmental disorders are discussed, alongside experimental approaches and key research reagents essential for investigating this rapidly advancing field.

The membrane-cytoskeleton interface is a specialized compartment where the plasma membrane and underlying cytoskeletal networks engage in continuous, bidirectional communication. This interface serves as a primary site for receiving extracellular information—including chemical gradients, mechanical forces, and topographical features—and converting these signals into coordinated intracellular responses [17]. The cytoskeleton, comprising actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, not only provides structural support but also functions as a dynamic signaling platform that integrates multiple extracellular cues to direct cell behavior [1].

The significance of this interface extends across numerous physiological processes. During embryonic development, coordinated deployment of cytoskeletal mechanisms drives tissue morphogenesis, as evidenced by basal constriction during optic cup formation [18]. In immune function, precise cytoskeletal remodeling enables T cells to migrate, form immunological synapses, and execute effector functions [19]. Pathologically, dysregulation of membrane-cytoskeleton signaling contributes to cancer metastasis, neurodegeneration, and immunodeficiencies, highlighting the therapeutic relevance of understanding these mechanisms [11] [1] [19].

A central feature of this interface is its capacity for spatial and temporal coordination of signaling events. Recent research has revealed that signaling and cytoskeletal components often self-organize into propagating wave patterns that define subcellular organization and enable rapid cellular responses to environmental changes [20]. These dynamic patterns represent a fundamental principle of cellular organization, allowing precise control over processes such as directed migration, phagocytosis, and cell division.

Molecular Mechanisms of Signal Integration at the Interface

Phosphoinositide Signaling in Cytoskeletal Regulation

Phosphoinositides (PIPns) serve as key membrane-associated signaling molecules that directly regulate cytoskeletal dynamics through interactions with various actin-binding proteins (ABPs). These lipids undergo reversible phosphorylation at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th positions of the inositol ring, generating seven distinct isoforms that localize to specific membrane compartments and recruit distinct effector proteins [11].

Table 1: Phosphoinositide Regulation of Actin-Binding Proteins

| PIPn Species | Target ABP | Effect on ABP | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ | Cofilin | Inhibits binding to actin | Stabilizes filaments, prevents disassembly |

| PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ | Profilin | Releases from actin | Increases monomer pool for polymerization |

| PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ | Gelsolin | Inhibits severing activity | Stabilizes actin network |

| PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ | Twinfilin | Inhibits monomer sequestration | Promotes polymerization |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P₃ | Profilin | Inhibits actin binding | Modulates actin assembly factor preference |

PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚, particularly concentrated at the plasma membrane, serves as a master regulator of actin dynamics by both inhibiting ABPs that promote disassembly and activating those that enhance polymerization [11]. For instance, PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ binding to cofilin prevents its interaction with actin filaments, thereby stabilizing the actin network [11]. Conversely, hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ releases cofilin, enabling filament severing and increased turnover. Similarly, PtdIns(4,5)Pâ‚‚ interaction with profilin regulates the availability of actin monomers for polymerization, effectively serving as a switch that controls actin assembly in response to external signals [21] [11].

The spatial restriction of PIPn signaling creates discrete functional domains at the membrane-cytoskeleton interface. During cell migration, PtdIns(3,4,5)P₃ accumulates at the leading edge, where it recruits proteins containing pleckstrin homology domains, including guanine nucleotide exchange factors that activate Rho GTPases [20]. This polarized distribution establishes front-rear asymmetry essential for directional migration.

Small GTPase Regulation of Cytoskeletal Dynamics

Small GTPases of the Rho family—particularly RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42—function as molecular switches that transduce signals from surface receptors to cytoskeletal rearrangements. These proteins cycle between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states, with activation promoting their association with membranes through lipid modifications [21].

Table 2: Small GTPase Functions in Cytoskeletal Organization

| GTPase | Primary Activator | Cytoskeletal Structure | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cdc42 | α-factor receptor (yeast) | Filopodia | Cell polarization, shmoo formation |

| Rac1 | Growth factors, integrins | Lamellipodia | Membrane ruffling, cell migration |

| RhoA | Lysophosphatidic acid | Stress fibers | Focal adhesion formation, contractility |

| Cdc42 | TCR engagement | Immunological synapse | T cell activation, polarity |

In budding yeast, Cdc42 activation in response to mating factor gradients directs polarized actin assembly toward the source of the signal, enabling directional growth during mating [22]. This polarization mechanism is evolutionarily conserved, with mammalian Cdc42 regulating filopodia formation through activation of neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP), which in turn activates the Arp2/3 complex to nucleate branched actin networks [22] [19].

The Rac1-WAVE2-Arp2/3 pathway drives lamellipodia formation in migrating cells, including fibroblasts and immune cells. Recent research has identified that the WAVE complex interacts with motif-containing membrane proteins, ranging from channels to adhesion molecules, providing a mechanism for coupling diverse surface receptors to actin polymerization [21]. Similarly, RhoA activation promotes stress fiber formation and contractility primarily through formin proteins such as mDia1 and mDia2, which nucleate linear actin filaments.

In T cells, coordinated activation of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA following T cell receptor engagement orchestrates immunological synapse formation. Cdc42 and Rac1 activate WASP and WAVE2 respectively, leading to Arp2/3-mediated branched actin polymerization at the synapse periphery, while RhoA-formin signaling generates contractile actin arcs in the inner synapse through myosin II activity [19].

Mechanotransduction Pathways

The membrane-cytoskeleton interface serves as the primary cellular site for mechanotransduction—the conversion of mechanical forces into biochemical signals. This process involves force-dependent changes in protein conformation, binding affinity, and activity at adhesion complexes [17].

Mechanosensitive ion channels, such as Piezo1, directly sense membrane tension and transmit calcium signals to the cytoskeleton. Additionally, force-dependent reinforcement of focal adhesions and adherens junctions occurs through changes in protein interactions. For example, mechanical tension increases α-catenin binding to actin and enhances association of the cross-linker α-actinin-4 with actin filaments [17]. Conversely, increased tension on single actin filaments reduces the binding rate of cofilin and delays severing [17].

Actin filaments themselves function as mechanosensors, with tension altering their structural conformation and interaction with ABPs. Mechanical stimulation induces rapid cytoskeletal remodeling, including localized depolymerization of microtubules at indentation sites and subsequent polymerization at the periphery [17]. Intermediate filaments, due to their high flexibility and extensibility, provide mechanical resistance and undergo reorganization in response to fluid shear stress in endothelial cells [17].

During optic cup morphogenesis in zebrafish, mechanical tensions generated by actomyosin contractility at the basal surface of retinal neuroblasts drive tissue folding. Laser ablation experiments revealed a developmental window during which local disruptions trigger global tissue relaxation, demonstrating supra-cellular transmission of mechanical tension dependent on extracellular matrix attachments [18].

Experimental Approaches for Studying the Interface

Live-Cell Imaging and Quantitative Analysis

Advanced live-cell imaging techniques enable direct visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics at the membrane interface. High-resolution time-lapse microscopy of fluorescently tagged cytoskeletal components (e.g., GFP-actin, RFP-tubulin) reveals dynamic behaviors including wave propagation, oscillatory contractions, and polarized growth.

In studying optic cup morphogenesis, researchers employed tg(vsx2.2:GFP-caax) zebrafish lines to monitor retinal precursor behavior during basal constriction [18]. Quantitative analysis of membrane pulsatile behavior and actomyosin dynamics demonstrated that myosin condensation correlates with episodic contractions that progressively reduce basal feet area. Similarly, imaging of actin waves in Dictyostelium and mammalian cells has elucidated how wave patterns define membrane protrusion morphologies and guide cell migration [20].

Experimental Protocol: Visualization of Actin Waves

- Transfect cells with F-tractin-GFP or LifeAct-mCherry to label F-actin

- Plate cells on glass-bottom dishes compatible with high-resolution microscopy

- Acquire time-lapse images every 2-5 seconds for 10-30 minutes using TIRF or confocal microscopy

- Maintain physiological temperature and COâ‚‚ levels throughout imaging

- Analyze wave propagation parameters (velocity, directionality, frequency) using kymographs and particle image velocimetry

Laser Ablation for Tension Mapping

Laser ablation serves as a powerful approach for mapping mechanical tensions within cells and tissues. This technique involves focused laser irradiation to sever specific cytoskeletal structures, followed by measurement of subsequent recoil dynamics to infer pre-existing tensions.

In zebrafish optic cup studies, laser ablation of the basal retinal epithelium during specific developmental windows triggered global tissue displacement, revealing the supra-cellular transmission of mechanical tension [18]. The recoil velocity following ablation provides a quantitative measure of tension, while the pattern of displacement maps force propagation through the tissue.

Experimental Protocol: Laser Ablation Tension Mapping

- Express fluorescent markers for cytoskeletal structures of interest (e.g., membrane-GFP, myosin-RFP)

- Identify target regions using confocal microscopy

- Apply focused laser pulses (typically 355nm or 405nm) to ablate 1-5μm regions

- Capture high-speed images (100-500ms intervals) immediately before and after ablation

- Quantify initial recoil velocity and displacement patterns using particle tracking algorithms

- Correlate mechanical properties with molecular perturbations (drug treatments, genetic manipulations)

Biochemical and Genetic Perturbation Approaches

Dissecting molecular mechanisms requires specific perturbation of candidate proteins followed by functional assessment. Genetic approaches include siRNA/shRNA knockdown, CRISPR-Cas9 knockout, and expression of dominant-negative or constitutively active mutants. Pharmacological inhibitors targeting cytoskeletal regulators (e.g., latrunculin for actin, nocodazole for microtubules, blebbistatin for myosin) enable acute manipulation of specific components.

In T cell studies, genetic deficiencies in WASP or ARPC1B reveal the essential roles of Arp2/3-mediated branched actin nucleation in immunological synapse formation and T cell activation [19]. Similarly, formin inhibition disrupts actin arc formation and TCR microcluster movement, demonstrating the complementary roles of different nucleation mechanisms [19].

Signaling and Actin Waves: A Systems-Level Perspective

Recent research has revealed that signaling and cytoskeletal components often self-organize into propagating wave patterns at the membrane-cytoskeleton interface. These waves represent a systems-level property of the underlying biochemical networks, enabling cells to define spatiotemporal dimensions for physiological processes [20].

Ventral waves of actin polymerization and associated signaling molecules (including PI(3,4,5)P₃, Ras, and Rho GTPases) have been observed across diverse cell types, from Dictyostelium to human neutrophils and cancer cells [20]. These waves regulate essential functions including cell polarity, random migration, macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and cytokinesis. In migrating cells, wave patterns directly control protrusion morphology—transitioning between lamellipodia, filopodia, and blebs based on the strengths of different signaling axes [20].

The excitable network dynamics underlying these waves enable cells to amplify stochastic fluctuations into coordinated behaviors and rapidly respond to external cues. For instance, in Dictyostelium cells, simultaneous regulation of PI(4,5)Pâ‚‚ levels and Ras activation induces instantaneous transitions in protrusion morphology and migratory mode [20]. Similarly, in embryonic systems, restriction of traveling actin polymerization waves by cell-cell contacts drives pulsed contractions essential for morphogenesis [20].

Figure 1: Signaling Wave Dynamics. Excitable network properties of signaling and cytoskeletal components generate propagating waves through positive feedback loops and delayed negative regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Membrane-Cytoskeleton Interface

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Biosensors | F-tractin-GFP, LifeAct-RFP, PIP₃ PH-domain biosensor | Live visualization of cytoskeletal and signaling dynamics | Real-time observation of actin waves, polarized signaling |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Latrunculin A/B (actin), Nocodazole (microtubules), Blebbistatin (myosin) | Acute disruption of specific cytoskeletal components | Dissection of force generation and transmission mechanisms |

| Genetic Tools | shCLIMP-63, WASP/ARPC1B mutants, Cdc42/Rac1/RhoA DN/CA mutants | Specific perturbation of molecular pathways | Identification of protein functions in cytoskeletal organization |

| Model Organisms | Zebrafish (tg(vsx2.2:GFP-caax), Dictyostelium, Yeast mutants | In vivo study of cytoskeletal dynamics in development | Discovery of basal constriction in optic cup morphogenesis |

| Advanced Microscopy | TIRF, FRAP, laser ablation, FIB-SEM | High-resolution spatial and temporal analysis | Mapping of mechanical tensions, ER-cytoskeleton interactions |

| Rose Bengal Sodium | Rose Bengal Sodium, MF:C20H2Cl4I4Na2O5, MW:1017.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Scandium(3+);triacetate;hydrate | Scandium(3+);triacetate;hydrate, MF:C6H11O7Sc, MW:240.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Dysregulation of membrane-cytoskeleton signaling underlies numerous pathological conditions, making this interface an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. In oncology, cancer cell invasion and metastasis depend on aberrant cytoskeletal dynamics and mechanotransduction. Increased Ras-PI(3,4,5)P₃-actin wave frequency in mammary epithelial cancer cells promotes metastasis by enhancing glycolysis and ATP production [20]. Matrix stiffening in breast cancer promotes microtubule glutamylation, affecting mechanical stability and promoting invasive behavior [17].

In immunology, mutations in cytoskeletal regulators cause severe immunodeficiencies. Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, resulting from WASP mutations, features defective T cell activation and cytoskeletal organization due to impaired Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization [19]. Similarly, ARPC1B deficiency leads to aberrant actin structures, unstable immune synapses, and defective cytotoxic function [19].

Neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, involve cytoskeletal pathologies. In Alzheimer's, tau protein malfunction compromises microtubule stability, while Parkinson's involves compromised microtubule assembly leading to neuronal degradation [1].

Emerging therapeutic strategies aim to modulate these pathways through small molecule inhibitors targeting key cytoskeletal regulators, with potential applications in cancer, autoimmune diseases, and neurological disorders. The development of compounds that specifically target pathological cytoskeletal dynamics while preserving normal cellular function represents an active frontier in drug discovery.

Figure 2: Clinical Implications of Membrane-Cytoskeleton Interface Dysregulation. Dysfunctional signaling at the interface contributes to diverse pathologies, inspiring targeted therapeutic strategies.

The membrane-cytoskeleton interface represents a sophisticated signaling compartment where extracellular information converges to direct coordinated cellular responses. Through integrated phosphoinositide signaling, small GTPase regulation, and mechanotransduction pathways, this interface translates diverse inputs into precise cytoskeletal rearrangements that govern cell behavior. The emergence of signaling waves as an organizing principle highlights the systems-level properties of these networks, enabling complex spatiotemporal control of cellular processes.

Future research directions include elucidating the molecular mechanisms enabling PIPns to specifically recognize distinct cytoskeletal components, identifying complete sets of PIPn-binding proteins involved in cytoskeletal regulation, and understanding how PIPn signaling pathways integrate with other networks to orchestrate cytoskeletal dynamics during development, homeostasis, and disease [11]. Advanced imaging technologies, biosensor development, and computational modeling will continue to reveal the exquisite subcellular organization and dynamic regulation of this critical cellular interface.

The therapeutic potential of targeting membrane-cytoskeleton interactions remains largely unexplored despite their crucial roles in disease pathogenesis [11]. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens, innovative approaches to modulate specific aspects of cytoskeletal dynamics may yield novel treatments for cancer, immunological disorders, and other conditions characterized by dysregulated cell behavior.

The physical forces experienced by a cell are not merely passive events but are potent biochemical signals that dictate fundamental cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival. This process of mechanotransduction—the conversion of mechanical stimuli into chemical activity—is orchestrated by key signaling hubs within the cell. Principal among these are the Rho GTPases and the YAP/TAZ transcriptional co-activators. These pathways form an integrated signaling network that senses and responds to the physical properties of the cellular microenvironment, such as extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness, cell geometry, and cell-cell contacts. Within the context of cytoskeletal dynamics, this network is a critical regulator of cellular architecture and behavior, driving processes essential in both normal tissue homeostasis and disease pathogenesis, including cancer and cardiovascular disorders. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these core pathways, details experimental methodologies for their study, and visualizes the complex signaling interplay that governs cellular decision-making.

Core Pathway Mechanics and Signaling Interplay

Rho GTPases: Masters of the Cytoskeleton

Rho GTPases function as molecular switches, cycling between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. This cycle is tightly controlled by three classes of regulatory proteins: Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) activate them, GTPase-Activating Proteins (GAPs) inactivate them, and Guanine nucleotide Dissociation Inhibitors (GDIs) sequester them in the cytoplasm. Once activated, Rho GTPases exert precise control over the actin cytoskeleton:

- RhoA promotes the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions, enabling contractility and stable cell adhesion.

- Rac1 stimulates the formation of lamellipodia, sheet-like membrane protrusions that drive forward movement during cell migration.

- Cdc42 induces the formation of filopodia, finger-like protrusions that sense the extracellular environment and guide migration.

The activity of Rho GTPases is directly modulated by mechanical cues. For instance, increasing ECM stiffness promotes RhoA activation through integrin-mediated signaling, leading to enhanced actomyosin contractility.

YAP/TAZ: Nuclear Effectors of Mechanical Cues

YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ (Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif) are the terminal effectors of the Hippo signaling pathway and function as potent transcriptional co-activators. Their activity is regulated by a complex array of biochemical and biomechanical signals.

- Canonical Hippo Pathway: In conditions of high cell density or an inactive state, the kinase cascade MST1/2 phosphorylates and activates LATS1/2. LATS1/2 then phosphorylates YAP/TAZ, leading to their cytoplasmic sequestration by 14-3-3 proteins or proteasomal degradation, effectively inhibiting their transcriptional function [23] [24].

- Hippo-Independent Regulation: YAP/TAZ are also regulated by other inputs, including GPCR signaling. Gα12/13-, Gαq/11-, or Gαi/o-coupled receptors inhibit LATS1/2 and promote YAP/TAZ activation, whereas Gαs-coupled receptors activate LATS1/2 and inhibit YAP/TAZ [24].

A key feature of YAP/TAZ is their role as mechanotransducers. They directly sense and respond to mechanical perturbations, including changes in ECM stiffness, cell shape, and cytoskeletal tension. In a permissive mechanical environment—such as low cell density or a stiff ECM—YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus. There, they partner primarily with TEAD transcription factors (and others like SMADs and AP-1) to drive the expression of target genes that regulate cell proliferation, survival, and stemness [23].

Table 1: Key Regulatory Inputs and Functional Outputs of YAP/TAZ

| Regulatory Input | Effect on YAP/TAZ | Primary Downstream Effect |

|---|---|---|

| High Cell Density / Cell-Cell Contact | Inactivation (Cytoplasmic retention) | Contact inhibition of proliferation |

| ECM Stiffness | Activation (Nuclear translocation) | Proliferation, Survival |

| GPCRs (Gα12/13, Gαq/11, Gαi/o) | Activation | Gene expression for growth & migration |

| GPCRs (Gαs) | Inactivation | Inhibition of proliferative programs |

| Energy Stress (AMPK) | Inactivation | Conservation of cellular energy |

| Mechanical Strain | Activation | Tissue expansion & remodeling |

The Integrated Rho-YAP/TAZ Signaling Axis

The Rho GTPase and YAP/TAZ pathways are not parallel but are deeply intertwined, forming a coherent mechanosignaling axis. The central link between them is the actin cytoskeleton. Activation of RhoA and its downstream effector ROCK leads to increased actin polymerization and actomyosin contractility. This reorganization of the cytoskeleton and the generation of intracellular tension are potent signals that inhibit the Hippo pathway kinases MST1/2 and LATS1/2, or promote the nuclear translocation of YAP/TAZ through other mechanisms, thereby activating YAP/TAZ [23] [24].

This creates a positive feedback loop: mechanical cues activate Rho → Rho-generated tension activates YAP/TAZ → YAP/TAZ transcriptional programs reinforce cytoskeletal dynamics and contractility. This loop is critical for sustaining phenotypes such as cancer cell invasion, fibroblast activation in fibrosis, and stem cell fate decisions.

Pathway Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core integrated signaling network connecting Rho GTPases, mechanosensing, and YAP/TAZ activation.

Diagram Title: Integrated Rho-YAP/TAZ Mechanosignaling Network

Experimental Analysis: Methodologies and Reagents

Studying the Rho-YAP/TAZ axis requires a multidisciplinary approach combining molecular biology, biochemistry, and live-cell imaging techniques.

Assessing YAP/TAZ Localization and Activity

A fundamental assay for YAP/TAZ activity is determining their subcellular localization, which serves as a direct readout of their functional state.

Protocol: Immunofluorescence for YAP/TAZ Localization

- Cell Seeding and Plating: Plate cells on substrates of varying stiffness (e.g., soft 0.5 kPa vs. stiff 50 kPa polyacrylamide gels) or at different densities (sparse vs. confluent) to manipulate mechanical signaling.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: After 24-48 hours, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Blocking and Staining: Block non-specific sites with 1-5% BSA or normal serum for 1 hour. Incubate with primary antibodies against YAP (e.g., Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-101199) and/or TAZ (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology, 70148) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Detection and Imaging: Wash and incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 or 568) for 1 hour at room temperature. Counterstain actin filaments with phalloidin (e.g., Cytoskeleton, Inc., PHDN1) and nuclei with DAPI. Image using a confocal or high-resolution fluorescence microscope.

- Analysis: Quantify the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity for YAP/TAZ using image analysis software like ImageJ (with plugins for cytoplasmic masking) or commercial high-content analysis systems. A high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio indicates pathway activation.

Alternative Methods:

- Fractionation and Immunoblotting: Separate nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions, followed by western blotting for YAP/TAZ. Lamin A/C and α-tubulin serve as nuclear and cytoplasmic markers, respectively.

- Luciferase Reporter Assays: Transfert cells with a reporter plasmid containing TEAD-responsive elements driving firefly luciferase expression (e.g., 8xGTIIC-luciferase). Measure luciferase activity as a direct indicator of YAP/TAZ-mediated transcription.

Modulating and Quantifying Rho GTPase Activity

Directly measuring the activation status of Rho GTPases is crucial for correlating their activity with YAP/TAZ behavior.

Protocol: RhoA Pull-Down Assay This assay uses the Rho-binding domain (RBD) of the effector protein Rhotekin, which specifically binds to the active, GTP-bound form of RhoA.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a buffer containing Mg²⺠to preserve the GTP-bound state of Rho proteins (e.g., 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors).

- Affinity Precipitation: Incubate the clarified cell lysates with glutathione Sepharose beads bound to GST-Rhotekin-RBD (available from Cytoskeleton, Inc., cat. # RT02). Gently rotate for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Washing and Elution: Pellet the beads and wash extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound, active RhoA-GTP by boiling the beads in Laemmli sample buffer.

- Detection: Resolve the eluted proteins and total cell lysate (input control) by SDS-PAGE. Perform western blotting using an anti-RhoA antibody (e.g., Cytoskeleton, Inc., cat. # ARH03). The level of RhoA in the pull-down fraction reflects its activated state.

Similar pull-down assays are available for Rac1 and Cdc42 using the p21-binding domain (PBD) of PAK1.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating the Rho-YAP/TAZ Axis

| Reagent / Tool | Supplier Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Rhotekin-RBD / PAK-PBD | Cytoskeleton, Inc.; Merck Millipore | Affinity purification of active, GTP-bound Rho GTPases (Pull-down assays). |

| YAP/TAZ Antibodies | Cell Signaling Technology; Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Detection of total protein, specific phosphorylation sites (e.g., YAP S127), and subcellular localization via IF/IHC. |

| TEAD Reporter Plasmid | Addgene (Plasmid #34615) | Luciferase-based reporter to measure functional YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity. |

| Inhibitors (VERTEPORFIN) | Selleck Chemicals | YAP/TAZ-TEAD interaction inhibitor; used to probe functional dependence on the pathway. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Tocris Bioscience | Inhibits ROCK kinase, reducing actomyosin contractility to dissect its role in YAP/TAZ activation. |

| Modular Substrates | Matrigen; Sigma-Aldrich | Tunable stiffness polyacrylamide or PDMS hydrogels to apply controlled mechanical cues to cells. |

| siRNA/shRNA Pools | Dharmacon; Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Targeted knockdown of YAP, TAZ, or Rho GTPases to establish genetic necessity in functional assays. |

| Water-18O | Water-18O H218O | |

| Sethoxydim | Sethoxydim, CAS:71441-80-0, MF:C17H29NO3S, MW:327.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Data Synthesis and Analysis

The interplay between mechanical forces, biochemical signaling, and transcriptional outputs generates complex, quantifiable data. Summarizing key quantitative relationships is essential for modeling and understanding this system.

Table 3: Quantitative Relationships in Rho-YAP/TAZ Signaling

| Parameter | Typical Experimental Range / Value | Measurement Technique | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear/Cytoplasmic YAP Ratio | 0.1-0.3 (High Density) vs. 3.0-8.0 (Low Density) | Quantitative Immunofluorescence | Direct measure of YAP/TAZ activation status; highly sensitive to cell crowding. |

| ECM Stiffness for YAP Activation | 0.5 kPa (Inactive) to >20 kPa (Active) | Cells plated on tunable hydrogels | Softer tissues (e.g., brain) suppress YAP/TAZ; stiffer tissues (e.g., bone, fibrotic tumors) activate it. |

| YAP/TAZ Target Gene Induction (CTGF, CYR61) | 2 to 50-fold increase upon activation | qRT-PCR, RNA-Seq | Magnitude indicates strength of downstream transcriptional program. |

| Active RhoA (GTP-bound) Levels | Can increase by 2-5 fold on stiff vs. soft ECM | RhoA G-LISA / Pull-down Assay | Correlates cytoskeletal activation with the mechanical properties of the substrate. |

| IC₅₀ for Y-27632 (ROCK Inhibitor) | ~0.1 - 10 µM | Dose-response in contractility / YAP localization assays | Effective concentration range for perturbing the mechanotransduction pathway. |

The signaling network comprising Rho GTPases, mechanotransduction, and YAP/TAZ pathways represents a fundamental regulatory module in cell biology. It exemplifies how cells continuously integrate physical information from their environment with traditional biochemical signals to govern their fate and behavior. A rigorous, multi-faceted experimental approach—combining the modulation of physical cues, precise biochemical assays, and quantitative imaging—is required to dissect this complex axis. As research continues to unravel the intricacies of these signaling hubs, they present promising therapeutic targets for a wide range of diseases, from inhibiting cancer progression and fibrosis to promoting tissue regeneration, by effectively reprogramming the cellular response to its physical environment.

The neuronal cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of protein filaments, is fundamental to maintaining neuronal structure, facilitating intracellular transport, and enabling synaptic plasticity. In neurodegenerative diseases, this intricate system undergoes profound dysregulation, driving the loss of neuronal structure and function that characterizes conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A growing body of evidence positions cytoskeletal instability not as a secondary consequence but as a primary driver of early pathogenesis in these disorders [25] [26]. The cytoskeleton comprises three core filament systems: microtubules, crucial for axonal transport and polarity; actin filaments, which govern synaptic spine dynamics; and neurofilaments, which provide structural support [25]. Understanding how defects in these components initiate and propagate neurodegeneration provides a critical framework for developing novel biomarkers and targeted therapeutics. This review dissects the molecular mechanisms of cytoskeletal failure across neurodegenerative diseases, framed within the broader context of cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular behavior research, to offer a strategic guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Mechanisms of Cytoskeletal Dysfunction

Microtubule Destabilization and Tau Pathology

Microtubules (MTs), composed of α/β-tubulin heterodimers, form the structural backbone of neurons, enabling the long-range transport of essential cargo. Their function is critically dependent on microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), most notably tau [25].

In Alzheimer's disease, tau undergoes a pathogenic transformation. Aberrant post-translational modifications (PTMs)—including hyperphosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination—at its microtubule-binding domain cause it to dissociate from MTs [25]. This loss of stabilizing contact leads to microtubule destabilization, impairing axonal transport and leading to synaptic dysfunction. The liberated, hyperphosphorylated tau subsequently aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), a hallmark of AD pathology [25] [26]. This creates a vicious cycle, as destabilized microtubules further promote tau aggregation [25].

The significance of MT instability is underscored by its role as one of the earliest pathological events in AD, potentially preceding the classical hallmarks of amyloid plaques and NFTs [26]. This insight has elevated MT dysregulation as a promising diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target.

Table 1: Key Proteins in Cytoskeletal Pathology and Their Roles

| Protein | Normal Function | Pathogenic Role | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | Stabilizes microtubules, regulates axonal transport | Hyperphosphorylation leads to MT dissociation, aggregation into NFTs | Alzheimer's Disease, FTD |

| TDP-43 | RNA binding and processing | Cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregation | ALS, FTD, LATE |

| Cofilin | Severs and depolymerizes actin filaments | Forms stable "cofilin-actin rods" under stress | AD, PD, Huntington's |

| Neurofilaments | Provides structural support to axons | Accumulation disrupts axonal transport | ALS, AD, PD |

Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling and Synaptic Failure

The actin cytoskeleton is the primary architectural element of dendritic spines, the sites of most excitatory synapses in the brain. Its dynamic remodeling is therefore essential for synaptic plasticity and stability. In neurodegeneration, this dynamism is hijacked, leading to spine destabilization and loss [25].

Pathological tau is again a key instigator, disrupting the Rho GTPase signaling pathways that tightly control actin polymerization [25]. Furthermore, recent research identifies specific mutations at the actin-ATP interface (e.g., K18A, D154A, G158L) as promoters of anomalous actin structures. These mutants induce the formation of cofilin-actin rods and large actin inclusions reminiscent of Hirano bodies, which are associated with AD and other dementias [27]. The persistence of cofilin-actin rods is particularly detrimental, as it leads to the sequestration of active actin and cofilin, resulting in the loss of dendritic spines and excitatory synapses [27].

Cross-Disease Proteomic Signatures and Cytoskeletal Involvement

Large-scale plasma proteomics studies comparing Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease (PD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) reveal both shared and disease-specific pathways involving the cytoskeleton. While immune and glycolytic pathways are commonly enriched across these diseases, specific cytoskeletal-related dysregulation varies [28].

For instance, network analyses have identified MAPK1 as a key upstream regulator in FTD, a kinase known to phosphorylate several cytoskeletal proteins [28]. Furthermore, the matrisome—a network of extracellular matrix and associated proteins—is another commonly dysregulated pathway, highlighting the importance of cell-matrix interactions, which are communicated intracellularly through the cytoskeleton [28].

Table 2: Plasma Proteomics Reveals Cytoskeleton-Associated Signals in Neurodegeneration

| Disease | Key Cytoskeleton-Associated Findings from Plasma Proteomics | Implicated Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Association with MAPT (tau); enrichment in microglial/macrophage cells | Apoptotic processes, immune response |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Dysregulation of proteins involved in ubiquitination and degradation | Protein degradation, endoplasmic reticulum-phagosome impairment |

| Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) | MAPK1 identified as a key upstream regulator | Platelet dysregulation, RNA processing |

Advanced Research Methodologies and Biomarkers

Imaging Microtubule Dynamics In Vivo

The recognition of MT instability as an early pathological event has spurred the development of novel imaging biomarkers. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) radiotracers that selectively bind to destabilized MTs now allow for the non-invasive visualization and quantification of MT dynamics in living subjects [26].

The radiotracer [\11C]MPC-6827 has demonstrated high specificity for destabilized MTs and excellent brain uptake in cross-species validation, from rodent models to humans [26]. This technology provides unprecedented insights into disease progression and offers a platform for evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring MT stability.

Functional and Behavioral Assessments

Simple, non-invasive cognitive tests that probe visual recognition memory are emerging as sensitive tools for early diagnosis. Color recognition memory tests have shown significant utility in differentiating individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD from cognitively healthy older adults [29].

The test involves presenting subjects with a set of colors and testing their recognition after delays (e.g., 5 and 30 minutes). The total error scores significantly increase across control, MCI, and mild AD groups, and adding this score to demographic and standard cognitive test data improves diagnostic accuracy from 77.9% to 84.4% [29]. This functional deficit is linked to pathology in the ventral visual stream and medial temporal lobe, areas critical for color recognition and memory that are affected early in AD [29].

Experimental Protocols for Cytoskeletal Research

Protocol: Investigating Actin Mutants Using an Optogenetic System

Objective: To characterize the role of specific actin residues in the formation of anomalous cytoskeletal structures associated with neurodegenerative disease.

Background: The CofActor (Cofilin Actin optically responsive) system is an optogenetic tool used to probe the stress-induced interaction between cofilin and actin. It consists of two protein fusions: Cryptochrome2-mCherry-Cofilin.S3E and beta Actin-CIB-GFP. The system allows for light- and stress-gated induction of cofilin-actin cluster formation, mimicking the formation of cofilin-actin rods [27].

Investigation of Actin Mutants Workflow

Methodology:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduce point mutations into the nucleotide-binding site of the beta Actin-CIB-GFP construct. Key residues to target include those interacting with the phosphate tail of ATP (e.g., K18, D154, G158, S14, K213) [27].

- Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture HeLa cells or primary cortical neurons in appropriate media.

- Co-transfect cells with the mutant (or wild-type) Actin-CIB-GFP construct and the Cry2-mCherry-Cofilin.S3E construct.

- Induction and Imaging:

- Homeostatic Conditions: Image for baseline actin distribution using widefield fluorescence microscopy.

- Stress Conditions: Induce energetic stress via ATP depletion (e.g., using sodium azide).

- Optogenetic Activation: Expose transfected cells to blue light (470 nm) to activate the Cry2-CIBN interaction, promoting cluster formation. Image cells every 30 seconds to monitor cluster dynamics [27].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Qualitatively assess actin distribution (normal, rod-like, large inclusions).

- Quantify cytosolic cluster formation using image analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ "Analyze Particles" feature).

- In neurons, assess impact on dendritic spine morphology.

Expected Outcomes: Mutations like K18A, D154A, and G158L will likely display aberrant phenotypes, such as forming cofilin-actin rods or large inclusions under homeostatic conditions, and will show a disrupted response to CofActor-mediated light activation compared to wild-type actin [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Neurodegeneration Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Specificity | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| CofActor Optogenetic System | Light- and stress-gated induction of cofilin-actin clusters. | Modeling anomalous actin structure formation in live cells [27]. |

| [\11C]MPC-6827 PET Tracer | Selectively binds destabilized microtubules. | Non-invasive, in vivo visualization of MT dynamics in animal models and humans [26]. |

| Anti-phospho-Tau Antibodies | Detect specific phospho-epitopes (e.g., Ser202, Thr205). | Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis of tau pathology in tissue and cell models. |

| Color Recognition Memory Test | Assesses visual recognition memory. | A simple, non-invasive behavioral test for early cognitive impairment in clinical studies [29]. |

| SomaScan Assay | Aptamer-based platform quantifying ~7,000 human proteins. | Large-scale, unbiased plasma proteomics to discover disease-associated signatures [28]. |

| Astrophloxine | Astrophloxine, MF:C27H33IN2, MW:512.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sodium metabisulfite | Sodium metabisulfite, CAS:7681-57-4; 7757-74-6, MF:Na2S2O5, MW:190.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Therapeutic Strategies and Future Directions

Targeting the cytoskeleton offers a multi-faceted approach to treating neurodegenerative diseases. The primary strategies under investigation include:

- Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents: Compounds like paclitaxel (and brain-penetrant derivatives) are being explored to counteract MT destabilization, restore axonal transport, and disrupt the vicious cycle of tau pathology [25] [26].

- Targeting Actin Dysregulation: Inhibiting the formation of cofilin-actin rods represents a promising strategy. This could involve developing molecules that stabilize the actin-ATP binding interface or that inhibit the pathological interaction between cofilin and ADP-actin [27].

- Multi-Target Interventions: Given the interplay between MTs, actin, and neurofilaments, effective therapies may need to simultaneously address instability across multiple cytoskeletal systems to restore overall homeostasis [25].

Future research must leverage advanced methods like super-resolution microscopy to visualize cytoskeletal structures at nanometer resolution and integrate findings from large-scale 'omics' datasets to build a complete molecular network of cytoskeletal dysfunction [30]. The ultimate goal is to translate these insights into precision interventions that can halt the structural collapse of neurons in Alzheimer's, ALS, and related disorders.

Cytoskeletal Dysregulation in Neurodegeneration

Advanced Techniques for Probing Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Research and Drug Discovery

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) and photoactivation (PA) represent cornerstone techniques in modern live-cell imaging for quantifying the dynamic behavior of molecules within living cells. These methods provide unparalleled insight into the kinetic properties of cellular components, enabling researchers to determine diffusion coefficients, mobile fractions, transport rates, and binding kinetics of fluorescently labeled molecules. Within the context of cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular behavior research, FRAP and PA have proven particularly valuable for understanding the rapid turnover and reorganization of actin networks, microtubules, and associated regulatory proteins [21] [18]. The ability to visualize and quantify protein dynamics in vesicles, organelles, and cells has provided new insights into fundamental processes such as mitosis, embryonic development, and cytoskeleton remodeling, which are crucial for understanding both normal physiology and disease states [31].

The application of these techniques to cytoskeletal research has revealed that many regulators of the cytoskeleton interact with membranes and exist in a dynamic equilibrium between monomeric and polymeric states [21]. For instance, studies of actin-binding proteins like profilin have demonstrated how membrane phosphoinositides can spatially regulate actin assembly by controlling the availability of these regulatory proteins [21]. Similarly, research on contractile actomyosin networks during zebrafish optic cup morphogenesis has utilized live imaging to reveal how myosin condensation correlates with episodic contractions that drive tissue folding [18]. Such findings underscore the critical importance of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions in coordinating cellular remodeling events.

Theoretical Foundations of Turnover Analysis

Fundamental Principles of FRAP and Photoactivation

FRAP operates on the principle of irreversibly bleaching fluorescent molecules in a defined region of interest (ROI) within a cell expressing a fluorescently tagged protein of interest, then monitoring the subsequent recovery of fluorescence into the bleached area over time [32]. This recovery occurs through the replacement of bleached molecules with unbleached ones from the surrounding environment, and the kinetics of this process reveal critical information about the mobility and binding characteristics of the studied molecules [32]. If fluorescent molecules are immobile, no fluorescence recovery will be observed, whereas highly mobile molecules exhibit rapid recovery kinetics.

Photoactivation represents a complementary approach wherein photoactivatable fluorescent molecules undergo a change in their absorption spectrum when illuminated with specific wavelengths, resulting in a dramatic increase (often 100-1000 fold) in fluorescence signal [33]. In fluorescence redistribution after photoactivation (FRAPa) experiments, molecules in a specified region are rapidly "turned on" using a high-intensity laser beam, and the subsequent redistribution of fluorescence due to diffusion is recorded through time-lapse imaging [33]. This approach typically generates higher signal-to-noise ratios with substantially lower light load compared to classic photobleaching experiments, reducing potential phototoxicity concerns [33].

Quantitative Parameters in Turnover Analysis

The fluorescence recovery curves generated from FRAP experiments provide three fundamental quantitative parameters that characterize protein dynamics:

- Mobile Fraction (Mf): The proportion of molecules that are free to diffuse and exchange between cellular compartments, calculated as the distance between the bleach depth and the recovered signal when kinetics reach a plateau [32].

- Immobile Fraction: The proportion of molecules that remain permanently bound within the bleached area, calculated as the distance between the recovered signal and the pre-bleach (100%) signal [32].

- Half-Time of Recovery (t½): The time required for fluorescence to reach half of its maximum recovery value, providing information about the speed of molecular movement [32].

- Diffusion Coefficient (D): A quantitative measure of molecular mobility, representing the area per unit time that molecules diffuse through the cellular environment [33] [34].

For cytoskeletal proteins, these parameters have revealed that despite a major fraction being bound to structural elements at any given moment, binding is typically transient with high turnover rates and residence times on the order of seconds [32]. This dynamic behavior is crucial for generating plasticity in cellular architecture and rapid response to signaling cues.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in FRAP/Photoactivation Analysis