Cytoskeletal Defects in Neurodegeneration: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

This article synthesizes current knowledge on cytoskeletal dysfunction as a central mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Huntington's disease.

Cytoskeletal Defects in Neurodegeneration: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on cytoskeletal dysfunction as a central mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Huntington's disease. We explore how defects in microtubules, neurofilaments, and actin filaments disrupt axonal transport, mitochondrial function, and neuronal integrity. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review examines emerging therapeutic strategies targeting cytoskeletal pathways, discusses methodological approaches and associated challenges, and evaluates cytoskeletal biomarkers for disease monitoring and therapeutic validation. The integration of foundational science with translational applications provides a comprehensive framework for developing novel interventions against these devastating disorders.

The Neuronal Cytoskeleton: Architecture and Core Pathologies in Neurodegeneration

The neuronal cytoskeleton, a complex and dynamic network, is fundamental to maintaining cellular structure, facilitating intracellular transport, and enabling neuronal plasticity. Comprised primarily of microtubules, neurofilaments, and actin filaments, this integrated system ensures proper neuronal function and viability. Increasing evidence indicates that defects in these cytoskeletal components and their regulatory mechanisms constitute a primary pathological feature in numerous neurodegenerative diseases. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the structure, function, and dynamics of these core filaments, frames their integrity within the context of neurodegeneration research, and presents current methodologies for investigating cytoskeletal defects. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing novel biomarkers and therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving neuronal health in conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

The cytoskeleton is an essential, dynamic network of filamentous proteins that extends throughout the cell cytoplasm, providing mechanical support, organizing intracellular contents, and facilitating crucial processes like cell division, motility, and intracellular transport [1] [2]. In neurons, the cytoskeleton takes on additional, specialized responsibilities due to the cells' extreme polarity and unique architectural demands. The elongated axons and complex dendrites of neurons, which can span remarkable distances, require a robust and adaptable internal scaffold to maintain their shape, resist mechanical stress, and enable the efficient transport of cargo between the cell body and distant synaptic terminals [3].

This neuronal scaffold is composed of three primary polymeric structures, classified by their diameter and biochemical composition: microtubules (~25 nm), neurofilaments (~10 nm), and actin filaments (~7 nm) [1] [2] [3]. Unlike static girders, these filaments form a dynamic system that is constantly being remodeled through assembly and disassembly, and their functions are finely tuned by a vast array of associated proteins, molecular motors, and post-translational modifications [4]. The coordinated interplay between these three systems allows the neuron to construct, maintain, and adapt its complex morphology over a lifetime.

The critical importance of the cytoskeleton for neuronal health is underscored by the fact that its collapse is a common hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases [3]. Defects in axonal transport, alterations in filament dynamics, and the accumulation of filamentous aggregates are observed in conditions including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [5] [3]. The resulting failure to transmit information and essential cargoes between the cell body and synapses triggers a "dying-back" degeneration of the neuron [3]. Consequently, the cytoskeleton is not merely a structural element but a central player in neurodegeneration, making its components prime targets for diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Core Components: Structure, Function, and Dynamics

Microtubules

Structure and Composition: Microtubules are the largest of the cytoskeletal filaments, with a diameter of approximately 25 nm [1] [6]. They are hollow cylinders composed of 13 linear protofilaments, each of which is a polymer of alternating α-tubulin and β-tubulin heterodimers [6]. This structure exhibits an inherent polarity, with a fast-growing plus end (exposed β-tubulin) and a slow-growing minus end (exposed α-tubulin) [6]. The minus end is typically anchored at the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC), while the plus end extends into the cellular periphery, a configuration critical for directional transport [6].

Dynamic Instability and Regulation: A defining characteristic of microtubules is dynamic instability, the stochastic switching between phases of growth and shrinkage [6]. This process is governed by GTP hydrolysis; the addition of GTP-bound tubulin stabilizes the growing end, while hydrolysis to GDP destabilizes the lattice, leading to rapid depolymerization (a "catastrophe") [6]. In neurons, microtubules are exceptionally stable, a property conferred by extensive post-translational modifications (e.g., acetylation, detyrosination) and stabilization by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) like tau and MAP2 [6] [3]. Neuronal microtubules are also highly organized; in axons, they exhibit a uniform plus-end-out orientation, whereas dendrites contain microtubules of mixed polarity [6].

Key Functions in Neurons:

- Intracellular Transport: Microtubules serve as tracks for the ATP-dependent movement of motor proteins. Kinesins typically transport cargo (e.g., vesicles, organelles) anterogradely toward the axon terminal, while dynein mediates retrograde transport back to the cell body [6] [3].

- Structural Support: They provide structural integrity to long axons and dendrites, resisting compressive forces [1].

- Neuronal Development: Microtubules are essential for neurite outgrowth, axon pathfinding, and the establishment of neuronal polarity during development [6].

Neurofilaments

Structure and Composition: Neurofilaments are the core type IV intermediate filaments of mature neurons, with a diameter of about 10 nm [1] [7]. They are composed of three principal subunits: neurofilament light (NF-L), medium (NF-M), and heavy (NF-H) chains, which co-assemble as obligate heteropolymers, often with α-internexin in the CNS or peripherin in the PNS [7]. Like all intermediate filament proteins, each subunit features a central α-helical rod domain flanked by variable head (N-terminal) and tail (C-terminal) domains [1] [7].

Assembly and Dynamics: Assembly begins with two monomers forming a parallel coiled-coil dimer. Two dimers then associate in an anti-parallel, staggered fashion to form a tetramer. Eight tetramers pack together to form a unit-length filament, which then anneals end-to-end to create the mature, ropelike polymer [1] [7]. This structure confers tremendous tensile strength. Neurofilaments are less dynamic than microtubules and actin and do not exhibit classic dynamic instability [1]. However, their organization and transport are highly dynamic and regulated by phosphorylation events on their head and tail domains [7].

Key Functions in Neurons:

- Radial Axonal Growth: Neurofilaments are the primary determinants of axonal caliber. A denser neurofilament network expands the axon's diameter, which in turn increases the conduction velocity of action potentials [7].

- Mechanical Strength: They provide mechanical strength, enabling neurons to withstand physical stress [1] [2].

- Synaptic Regulation: Specific subunits interact with synaptic components; for example, NF-L binds to the NMDA receptor and myosin Va, thereby influencing synaptic vesicle dynamics and receptor anchoring [7].

Actin Filaments

Structure and Composition: Actin filaments (or microfilaments) are the thinnest cytoskeletal filaments, with a diameter of roughly 7 nm [1] [2]. They are helical polymers of the protein actin, which exists as a globular monomer (G-actin) that polymerizes into filamentous F-actin [4]. The filament is polarized, featuring a fast-growing barbed end (plus end) and a slow-growing pointed end (minus end) [4].

Dynamics and Regulation: Actin filaments undergo rapid assembly and disassembly, a process controlled by a host of actin-binding proteins. Profilin promotes actin polymerization, while cofilin severs and depolymerizes existing filaments [4] [5]. The Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rho, Rac, Cdc42) acts as master regulators, integrating extracellular signals to orchestrate large-scale actin remodeling [4]. This allows the actin cytoskeleton to be rapidly rebuilt in response to cellular needs.

Key Functions in Neurons:

- Cell Motility and Morphogenesis: Actin is the primary driver of cell crawling and, in neurons, the motility of the growth cone at the tip of a developing axon [4].

- Structural Cortex: A meshwork of actin filaments underneath the plasma membrane, known as the cell cortex, provides structural stability and defines cell shape [4] [1].

- Synaptic Plasticity: Actin is highly enriched in dendritic spines and presynaptic terminals, where its dynamic remodeling is essential for the formation, maintenance, and structural changes underlying synaptic plasticity and learning [3].

- Cargo Transport: While microtubules are the highways for long-range transport, actin facilitates short-range movements and the final positioning of cargo near the membrane [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Core Cytoskeletal Components

| Feature | Microtubules | Neurofilaments | Actin Filaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~25 nm [1] [6] | ~10 nm [1] [7] | ~7 nm [1] [2] |

| Protein Subunit | α/β-Tubulin heterodimer [6] | NF-L, NF-M, NF-H [7] | Actin [4] |

| Polymer Polarity | Yes (Plus/Minus end) [6] | No (Apolar) [1] | Yes (Barbed/Pointed end) [4] |

| Nucleotide Hydrolysis | GTP [6] | Not applicable | ATP [4] |

| Dynamic Instability | Yes [6] | No [1] | Yes (Treadmilling) [4] |

| Primary Motor Proteins | Kinesin, Dynein [6] | Myosin Va [7] | Myosin [4] |

| Key Neuronal Function | Long-range transport, Structural support [6] | Axonal caliber determination, Mechanical strength [7] | Growth cone motility, Synaptic plasticity [4] |

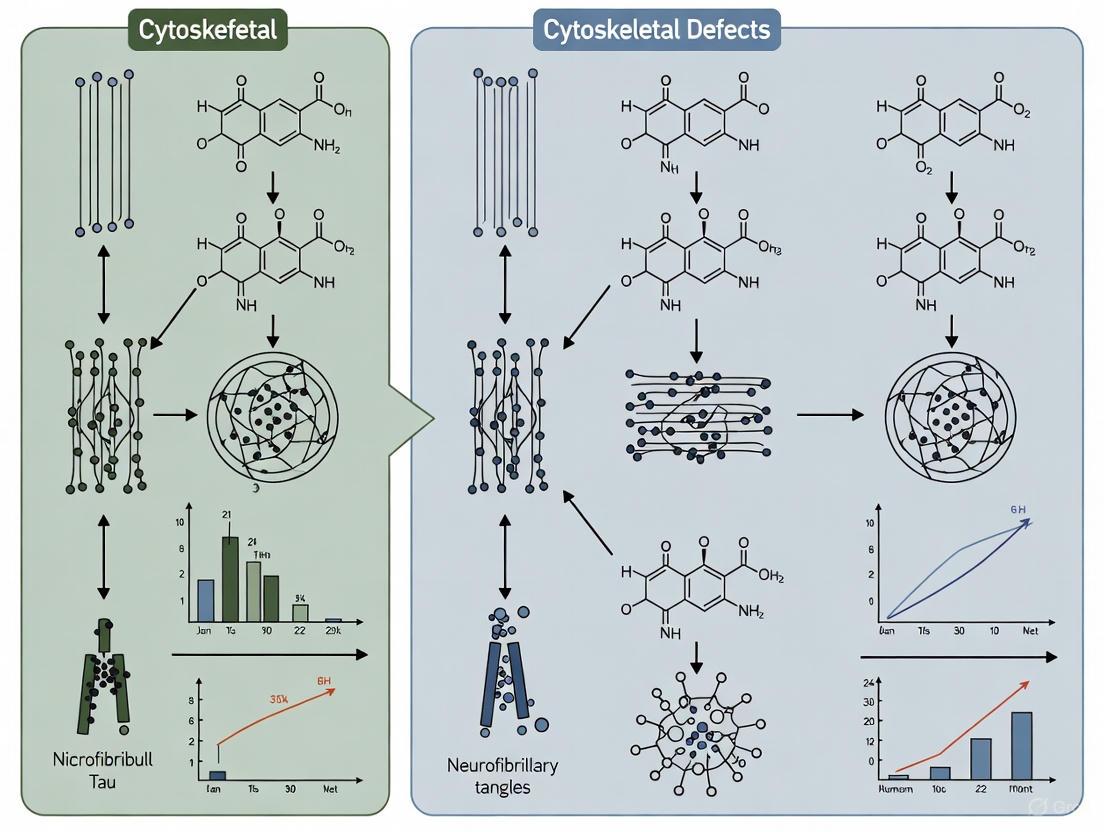

Cytoskeletal Defects in Neurodegeneration Mechanisms

The proper function of the cytoskeletal network is paramount for neuronal survival, and its disruption is a convergent mechanism in many neurodegenerative diseases. These defects often manifest as impaired axonal transport, aberrant filament aggregation, and a breakdown of structural integrity, ultimately leading to the characteristic "dying-back" neuropathy where the synapse degenerates first [3].

Microtubule Dysregulation

Microtubule instability is one of the earliest pathological events in several neurodegenerative disorders [6]. In Alzheimer's disease (AD), the microtubule-associated protein tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, causing it to detach from microtubules. This leads to microtubule destabilization and the self-aggregation of tau into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), a key pathological hallmark of the disease [6] [3]. The loss of functional tau from microtubules compromises axonal transport, depriving synapses of essential components. Furthermore, mutations in the MAPT gene encoding tau are directly linked to frontotemporal dementia, providing genetic evidence for the central role of microtubule dysfunction in neurodegeneration [3].

In Parkinson's disease (PD) and ALS, microtubule dysregulation also contributes to impaired intracellular trafficking and loss of neuronal integrity [6]. Mutations in genes encoding proteins involved in the axonal transport machinery, such as kinesin family member 5A (KIF5A) and dynactin (DCTN1), are associated with ALS and other neuropathies, directly linking transport defects to disease pathogenesis [3].

Neurofilament Aggregation and Pathophysiology

The accumulation of neurofilaments is a long-observed feature in ALS, PD, and AD [7]. While historically considered a secondary phenomenon, the discovery of rare neurological disorders caused by mutations in NF genes has solidified their primary pathogenic role. For example, mutations in the NEFL gene cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2E, a peripheral neuropathy, by interfering with normal neurofilament assembly and transport [3] [7].

The mechanism of NF aggregation often involves hyperphosphorylation, particularly of the side-arm domains of NF-M and NF-H [7]. This aberrant phosphorylation can alter ionic interactions between subunits, disrupt their binding to molecular motors, and protect NFs from proteolysis, ultimately leading to their accumulation and aggregation in axonal swellings [7]. These aggregates physically obstruct axonal transport and are thought to contribute to the degeneration of motor neurons in ALS. Notably, neurofilament proteins themselves, especially the light chain (NF-L), have emerged as highly sensitive biomarkers in patient biofluids (blood and CSF) for monitoring neurodegeneration across a spectrum of diseases, including ALS and SMA [5] [3].

Actin Dynamics and Synaptic Failure

Defects in the actin cytoskeleton are increasingly recognized as a key factor in synaptic failure and neurodegeneration. Mutations in profilin 1 (PFN1), an actin-binding protein that regulates polymerization, are a cause of familial ALS [3]. These mutations lead to cytoskeletal defects, including impaired axonal outgrowth. In Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), caused by a deficiency in the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein, there is a profound disruption of actin dynamics in growth cones and synapses, contributing to the selective vulnerability of motor neurons [5]. Furthermore, in Huntington's disease and Fragile X syndrome, aberrant actin regulation in dendritic spines underlies the observed deficits in synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [3].

Table 2: Cytoskeletal Defects in Select Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Key Cytoskeletal Defects | Associated Genes/Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Tau hyperphosphorylation & NFT formation; Microtubule destabilization; NF accumulation [6] [3] [7] | MAPT (Tau) [3] |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Microtubule dysfunction; Impaired axonal transport; Presence of NFs in Lewy bodies [6] [7] | |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | NF aggregates in axons; Mutated actin-regulating proteins; Impaired axonal transport [3] [7] | SOD1, TDP-43, PFN1, KIF5A [3] |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease (CMT2E) | Disorganized NF network; Disrupted NF assembly and transport [3] [7] | NEFL [3] |

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | Impaired actin dynamics in growth cones; Destabilization of microtubules; Altered profiling and plastin levels [5] | SMN1 [5] |

| Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) | Tau pathology leading to microtubule instability [3] | MAPT [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Cytoskeletal Research

Analyzing Neurofilament-Motor Protein Interactions

Objective: To characterize the direct interaction between neurofilament subunits and the cytoplasmic dynein motor complex.

Method Details:

- Protein Purification: Isolate native neurofilaments from central nervous system tissue (e.g., bovine spinal cord) via differential centrifugation. Purity is assessed by SDS-PAGE, confirming the presence of the NF triplet proteins (NF-L, NF-M, NF-H) constituting >95% of total protein [8]. Purify the dynein/dynactin complex from brain tissue using microtubule affinity and ATP-dependent release, followed by sucrose gradient sedimentation [8].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Deposit diluted protein samples (NFs, dynein/dynactin, or mixtures) onto freshly cleaved mica. Image in fluid tapping mode to visualize single molecules and complexes in an unfixed, unstained state. To quantify binding frequency, scan along the contour of multiple neurofilaments and measure height profiles. A localized height increase >15 nm (sum of NF height ~8 nm and dynein height ~6 nm) is scored as a binding event [8].

- Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening: Use a human brain library to screen for proteins that interact with the dynein intermediate chain (DIC). Identify positive clones encoding interacting proteins, such as fragments of NF-M, via DNA sequencing and database searching. This confirms a direct protein-protein interaction [8].

- Inhibition Assays: Pre-incubate neurofilaments or dynein with function-blocking monoclonal antibodies. Subsequent AFM imaging or in vitro motility assays is used to assess the disruption of the NF-dynein interaction, validating the specificity of the binding [8].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for characterizing NF-motor protein interaction.

Profiling Cytoskeletal Gene Expression in Age-Related Diseases

Objective: To identify transcriptionally dysregulated cytoskeletal genes as potential biomarkers for age-related neurodegenerative and other diseases.

Method Details:

- Data Acquisition: Retrieve transcriptome data (e.g., RNA-Seq) from public repositories for disease cohorts (e.g., Alzheimer's, Cardiomyopathy) and matched controls. Obtain a curated list of cytoskeletal genes from the Gene Ontology term GO:0005856 [9].

- Machine Learning Feature Selection: Employ Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) coupled with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. The RFE-SVM model is trained on the expression data of cytoskeletal genes and recursively prunes the least important features, identifying a minimal subset of genes that best discriminates patients from controls. Validate model performance using 5-fold cross-validation [9].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Independently analyze the transcriptome data using tools like

DESeq2orLimmato identify cytoskeletal genes with statistically significant (e.g., adjusted p-value < 0.05) expression changes between disease and control groups [9]. - Data Integration and Validation: Identify the overlapping genes from the RFE-selected features and the differential expression analysis. Validate the diagnostic power of these candidate biomarker genes using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis on external, independent datasets [9].

Diagram 2: Computational pipeline for cytoskeletal biomarker discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cytoskeletal Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Microtubule-stabilizing drug. Binds to and stabilizes polymerized microtubules, suppressing dynamic instability [8] [6]. | Used in protein purification to stabilize microtubules for motor protein assays; employed in cellular models to study the effects of hyper-stable microtubules [8]. |

| Profilin & Cofilin | Actin-binding proteins. Profilin promotes G-actin polymerization; Cofilin severs and depolymerizes F-actin [4] [5]. | Used in in vitro actin polymerization assays to manipulate dynamics; studied in cellular models of ALS (mutant PFN1) and SMA to understand pathogenesis [5] [3]. |

| Function-Blocking Antibodies | Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the activity of specific target proteins. | Antibodies against dynein IC or NF-M used in AFM/in vitro assays to block and study specific protein interactions [8]. |

| SOMAmer Technology | Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamers; a high-throughput proteomic platform for measuring thousands of proteins in biofluids [10]. | Used in large consortia (e.g., GNPC) to discover and validate protein biomarkers, including cytoskeletal proteins like neurofilaments, in plasma and CSF [10]. |

| [11C]MPC‑6827 | A positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer that selectively binds to destabilized microtubules [6]. | Enables non-invasive, in vivo imaging of microtubule instability in the brains of living patients with AD or PD, serving as a translational diagnostic tool [6]. |

| Tubulin & Actin Polymerization Assay Kits | Commercial kits containing purified proteins and buffers to monitor in vitro polymerization in real-time (e.g., via fluorescence). | Used for high-throughput screening of compounds that modulate microtubule or actin dynamics for drug discovery [6]. |

The essential cytoskeletal components—microtubules, neurofilaments, and actin filaments—form an integrated, dynamic network that is fundamental to neuronal architecture, function, and survival. The precise regulation of their assembly, disassembly, and transport is critical for maintaining axonal integrity, synaptic connectivity, and cellular homeostasis. As detailed in this whitepaper, the breakdown of this delicate balance is a central mechanism in the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases. The convergence of genetic, biochemical, and histopathological evidence firmly establishes cytoskeletal defects not as a mere secondary consequence but as a primary driver of neurodegeneration.

Current research, leveraging advanced techniques from atomic force microscopy and machine learning to in vivo PET imaging, is rapidly translating this knowledge into clinical applications. The emergence of neurofilament proteins as fluid biomarkers and the development of tracers for microtubule stability herald a new era for early diagnosis and disease monitoring. Future therapeutic efforts aimed at directly stabilizing the cytoskeleton, modulating the activity of associated proteins, or correcting aberrant post-translational modifications hold significant promise. For researchers and drug development professionals, targeting the cytoskeleton offers a powerful, mechanistic approach to developing the next generation of treatments for neurodegenerative disorders.

Cytoskeletal Defects as a Unifying Hallmark Across Neurodegenerative Disorders

The neuronal cytoskeleton is an intricate, dynamic network essential for maintaining neuronal structure, facilitating intracellular transport, and supporting synaptic function. Comprising three primary polymeric structures—microtubules (composed of tubulin), intermediate filaments (neurofilaments), and actin-based microfilaments—this complex system enables neurons to construct, maintain, and modify their elaborate architecture [3]. In neurodegenerative diseases, this carefully orchestrated system undergoes progressive disintegration, leading to a cascade of cellular failures. Cytoskeletal defects represent a fundamental pathological hallmark shared across diverse neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Huntington's disease (HD) [3] [11]. These defects disrupt critical cellular processes, ultimately resulting in the characteristic clinical manifestations of these devastating conditions.

The significance of cytoskeletal pathology in neurodegeneration is underscored by its recent identification as one of the eight core hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases, alongside pathological protein aggregation, synaptic dysfunction, aberrant proteostasis, altered energy homeostasis, DNA/RNA defects, inflammation, and neuronal cell death [11] [12]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms linking cytoskeletal abnormalities to neurodegenerative processes, presents current experimental methodologies for their investigation, and explores emerging therapeutic strategies targeting cytoskeletal integrity.

Molecular Composition and Functions of the Neuronal Cytoskeleton

Core Cytoskeletal Components

The neuronal cytoskeleton consists of three structurally and functionally distinct filament systems that collectively determine cell morphology, mechanical properties, and intracellular organization. Microtubules, the stiffest of the three polymers, are hollow tubes composed of αβ-tubulin heterodimers with a persistence length of approximately 5 mm, enabling them to form nearly linear tracks that span the considerable length of mature neurons [13]. These structures serve as primary highways for intracellular transport, guiding the movement of vesicles, organelles, and cargo via molecular motor proteins including kinesins and dyneins [13]. Actin filaments (microfilaments) are more flexible polymers that organize into complex networks and bundles beneath the plasma membrane and at synaptic terminals. They are crucial for maintaining cell shape, facilitating motility, and mediating structural plasticity at dendritic spines and other specialized neuronal compartments [13] [3]. Intermediate filaments, particularly neurofilaments in mature neurons, provide crucial mechanical strength and regulate axon diameter, thereby influencing conductivity velocity and structural integrity [3].

Regulatory Proteins and Molecular Interactions

The organization and dynamics of these cytoskeletal networks are controlled by numerous regulatory proteins that govern assembly, disassembly, and higher-order organization. Key regulators include nucleation-promoting factors that initiate filament formation, capping proteins that terminate filament growth, polymerases that promote sustained elongation, depolymerizing factors that disassemble filaments, and crosslinkers that organize higher-order network structures [13]. Particularly important in neuronal contexts are microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) such as tau, which stabilize microtubules and regulate motor protein access [3]. The actin cytoskeleton is similarly regulated by proteins like cofilin (which severs and depolymerizes actin filaments), profilin (which promotes actin polymerization), and formins (which nucleate linear actin filaments) [13] [14]. Cross-linking proteins including bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BPAG1) and microtubule actin cross-linking factor 1 (MACF1) stabilize connections between different cytoskeletal elements, creating an integrated network [3].

Table 1: Major Cytoskeletal Components in Neurons and Their Primary Functions

| Cytoskeletal Element | Protein Composition | Key Functions | Regulatory Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microtubules | αβ-tubulin heterodimers | Intracellular transport, structural support, mitotic spindle organization | Tau, MAP2, kinesin, dynein |

| Actin Filaments | Actin | Cell shape determination, structural plasticity, endocytosis, cytokinesis | Cofilin, profilin, formins, WAVE complex |

| Intermediate Filaments | Neurofilament proteins (NFL, NFM, NFH) | Mechanical strength, axon caliber regulation, organelle positioning | Kinases, phosphatases |

Cytoskeletal Defects in Major Neurodegenerative Diseases

Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's disease presents profound cytoskeletal pathology characterized by neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. In healthy neurons, tau normally stabilizes microtubules and promotes their assembly. In AD, abnormal phosphorylation of tau reduces its affinity for microtubules, leading to microtubule destabilization and collapse of the transport system [3]. The dissociated tau subsequently aggregates into paired helical filaments and eventually neurofibrillary tangles, which represent a defining neuropathological feature of the disease [15] [3]. Beyond tau pathology, actin cytoskeleton abnormalities also contribute to AD pathogenesis. Recent research has identified that mutations to the actin-ATP interface (K18A, D154A, G158L, K213A) promote the formation of disease-associated actin-rich structures including cofilin-actin rods and Hirano bodies, which disrupt synaptic function and contribute to spine loss [14].

Parkinson's Disease

While Parkinson's disease is traditionally characterized by Lewy bodies containing aggregated α-synuclein, emerging evidence indicates significant cytoskeletal involvement in its pathogenesis. Mutations in genes encoding the microtubule-associated protein tau have been identified as risk factors for PD, suggesting shared pathogenic mechanisms with primary tauopathies [3]. Additionally, defects in axonal transport machinery have been documented in PD models, with impaired mitochondrial trafficking contributing to the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [3]. The actin cytoskeleton also undergoes alterations in PD, with disruptions in actin-binding proteins contributing to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death [16].

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

ALS demonstrates prominent cytoskeletal pathology manifested through abnormalities in all three cytoskeletal systems. Mutations in the gene encoding neurofilament light chain (NEFL) cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2E, with mutant NEFL interfering with proper neurofilament assembly and transport [3]. Additionally, mutations in profilin 1 (PFN1), an actin-binding protein, lead to ALS pathogenesis through disrupted actin polymerization and the formation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates [3]. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) inclusions, a pathological hallmark of most ALS cases, are associated with impaired axonal transport and cytoskeletal disorganization, ultimately leading to the degeneration of motor neurons [3].

Frontotemporal Dementia and Huntington's Disease

Frontotemporal dementia frequently involves direct tau pathology, with mutations in the MAPT gene encoding tau leading to familial forms of the disorder [3]. These mutations result in microtubule destabilization and breakdown of the neuronal cytoskeleton, accompanied by the formation of toxic tau aggregates [3]. In Huntington's disease, mutant huntingtin protein disrupts vesicular transport along microtubules by interfering with molecular motor proteins, particularly kinesin-1 and dynein [3]. This transport deficit contributes to the selective vulnerability of striatal neurons, even though huntingtin itself is widely expressed throughout the brain.

Table 2: Cytoskeletal Defects in Major Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Primary Cytoskeletal Defects | Associated Gene Mutations | Resulting Pathological Inclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Tau hyperphosphorylation, microtubule destabilization, actin rod formation | MAPT (tau) | Neurofibrillary tangles, cofilin-actin rods, Hirano bodies |

| Parkinson's Disease | Impaired axonal transport, tau pathology, actin dynamics disruption | MAPT | Lewy bodies, neurofibrillary tangles |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | Neurofilament aggregation, disrupted actin polymerization, impaired transport | NEFL, PFN1, TDP-43 | Neurofilament aggregates, ubiquitinated inclusions |

| Frontotemporal Dementia | Tau dysfunction, microtubule instability | MAPT | Tau inclusions, neurofibrillary tangles |

| Huntington's Disease | Disrupted vesicular transport, impaired motor protein function | HTT (huntingtin) | Huntingtin aggregates |

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Cytoskeletal Defects to Neurodegeneration

Disrupted Axonal Transport

The extreme polarity and considerable length of neurons make them uniquely dependent on efficient axonal transport for their survival and function. The cytoskeleton provides the structural framework for this transport, with microtubules serving as tracks for motor proteins that carry essential cargo between the cell body and synaptic terminals [13] [3]. Cytoskeletal disruptions directly impair this critical process, leading to a "dying-back" pattern of degeneration where distal synapses and axons degenerate before the cell body [3]. Mutations in genes encoding components of the axonal transport machinery, including kinesin family member 5A (KIF5A) and dynactin 1 (DCTN1), have been directly linked to ALS and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, highlighting the fundamental importance of intact transport systems for neuronal health [3]. The collapse of efficient transport results in improper distribution of vesicles, organelles (including mitochondria), and essential components between the cell body and synaptic endings, ultimately compromising synaptic function and neuronal viability [3].

Actin Dynamics and Synaptic Dysfunction

The actin cytoskeleton plays particularly important roles at synapses, where it forms the structural core of dendritic spines and participates in the trafficking of neurotransmitter receptors. Defects in actin regulatory proteins have been implicated in multiple neurodegenerative conditions. For example, mutations in profilin 1 (PFN1), which promotes actin polymerization, cause ALS by disrupting actin dynamics and leading to the formation of pathological inclusions [3]. Similarly, abnormalities in LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1), which phosphorylates and inactivates the actin depolymerizing factor cofilin, have been associated with spine morphology defects in Williams syndrome [3]. Recent research has demonstrated that specific mutations at the actin-ATP interface (K18A, D154A, G158L, K213A) promote the formation of cofilin-actin rods and Hirano bodies under conditions of cellular stress, providing a direct mechanistic link between actin pathology and neurodegenerative processes [14]. These actin-rich aggregates sequester essential actin-binding proteins, disrupt synaptic function, and contribute to the elimination of excitatory synapses [14].

Cytoskeletal Cross-Talk and Integration

The different components of the cytoskeleton do not function in isolation but rather engage in extensive cross-talk that integrates their activities. Plakins such as BPAG1 and MACF1 physically cross-link different cytoskeletal elements, allowing coordinated responses to mechanical and biochemical signals [3]. The Rho GTPase family members, including RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, serve as key regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics, controlling actin organization and microtubule stability through complex signaling networks [3]. During neurodegeneration, disruptions to this integrated cytoskeletal network become progressively amplified through positive feedback loops. For example, activation of the RhoA signaling pathway leads to cytoskeletal remodeling, which in turn activates myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF), promoting the expression of fibrosis-related genes and further strengthening RhoA signaling [17].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Investigating Actin Pathology Using the CofActor System

Recent advances in optogenetic tools have enabled more precise investigation of cytoskeletal dynamics in living cells. The CofActor system represents an innovative approach for studying actin-cofilin interactions in a light- and stress-gated manner [14]. This system consists of two primary components: (1) a blue-light responsive cryptochrome 2 (Cry2)-Cofilin.S3E protein fusion, and (2) a betaActin-CIB protein fusion [14]. Upon blue light activation in the presence of cellular stress (e.g., ATP depletion), these components interact to form cytoplasmic clusters that can be quantitatively monitored using live-cell imaging techniques.

Experimental Protocol for CofActor Analysis:

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Plate HeLa cells or primary cortical neurons in appropriate culture conditions. Transfect with CofActor constructs (Cry2-mCherry-Cofilin.S3E and betaActin-CIB-GFP) using standard transfection methods.

- Stress Induction: Induce energetic stress using mitochondrial inhibitors (e.g., sodium azide) or oxidative stress using glutamate excitotoxicity models.

- Optogenetic Activation: Expose cells to 470 nm blue light to activate the Cry2-CIBN interaction system. Typically, light activation for 30-second intervals followed by imaging every 30 seconds provides optimal temporal resolution.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Capture time-lapse images using widefield or confocal microscopy. Quantify cluster formation using image analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ) with the Analyze Particles feature to determine particle counts, size distribution, and fluorescence intensity over time.

- Mutant Analysis: Introduce specific point mutations into the actin-ATP interface (e.g., K18A, D154A, G158L, K213A) to investigate their effects on cluster formation under stress conditions.

This methodology has revealed that mutations at the actin-ATP interface significantly alter the propensity to form anomalous actin structures, providing insight into how specific actin residues contribute to neurodegenerative disease progression [14].

Diagram 1: CofActor experimental workflow for analyzing actin-cofilin interactions.

Advanced Imaging and Visualization Techniques

The investigation of cytoskeletal defects in neurodegeneration relies heavily on advanced imaging methodologies that enable visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics in live cells and intact tissues. Recent advances in the visualization of the microtubule and actin cytoskeleton in multicellular organisms have provided unprecedented insights into cytoskeletal organization and dynamics [3]. Key approaches include:

- High-resolution live-cell microscopy using GFP-tagged cytoskeletal proteins to monitor dynamics in real-time

- Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy for visualizing cytoskeletal structures near the plasma membrane

- Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) and stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy to overcome diffraction limits and resolve fine cytoskeletal details

- Electron microscopy techniques for ultrastructural analysis of cytoskeletal organization

- Combined approaches that correlate light and electron microscopy data to bridge resolution gaps

These techniques have revealed that both internal and external physical forces can act through the cytoskeleton to affect local mechanical properties and cellular behavior, with long-lived cytoskeletal structures potentially serving as epigenetic determinants of cell shape, function, and fate [13].

Therapeutic Approaches and Research Reagents

Targeting Cytoskeletal Pathways

Current therapeutic strategies for addressing cytoskeletal defects in neurodegenerative diseases focus on normalizing cytoskeletal dynamics, enhancing axonal transport, and reducing pathological protein aggregation. These approaches include:

Microtubule-Stabilizing Compounds:

- Epothilone D - crosses the blood-brain barrier and enhances microtubule stability, shown to improve axonal transport and reduce tau pathology in animal models of AD

- TPI-287 - a taxane-derived microtubule stabilizer evaluated in clinical trials for AD and PSP

- Naturally occurring compounds such as paclitaxel and its derivatives, which reduce microtubule dynamics but face challenges with blood-brain barrier penetration

Actin Dynamics Modulators:

- Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors - target the RhoA-ROCK pathway involved in stress fiber formation and neurite retraction

- Cofilin inhibitors - designed to prevent pathological cofilin-actin rod formation

- Blebbistatin - a selective inhibitor of non-muscle myosin II that reduces actin-myosin contractility

Signaling Pathway Modulators:

- LIMK inhibitors - target the kinase responsible for cofilin phosphorylation, potentially normalizing actin dynamics

- Rho GTPase modulators - influence multiple cytoskeletal regulatory pathways

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cytoskeletal Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic Tools | CofActor system (Cry2-Cofilin.S3E, betaActin-CIB) [14] | Live-cell imaging of actin-cofilin dynamics | Light- and stress-gated monitoring of cytoskeletal protein interactions |

| Chemical Inhibitors/Activators | Rho kinase inhibitors (Y-27632), Microtubule stabilizers (Taxol), Cofilin inhibitors | Pathway modulation in cellular and animal models | Targeted manipulation of specific cytoskeletal regulatory pathways |

| Live-Cell Probes | GFP-tagged cytoskeletal proteins, SiR-actin/tubulin stains, Photoactivatable probes | Real-time visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics | Fluorescent labeling and tracking of cytoskeletal components |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, siRNA/shRNA knockdown, Mutant constructs (K18A, D154A actin) [14] | Genetic manipulation of cytoskeletal components | Selective alteration of specific cytoskeletal proteins and their regulators |

Multi-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Given the complexity of cytoskeletal defects in neurodegenerative diseases, effective therapeutic approaches will likely require multi-targeted strategies that address multiple pathological processes simultaneously [16] [11]. Promising approaches include:

- Combination therapies that simultaneously target cytoskeletal integrity and disease-specific protein aggregation

- Disease-modifying strategies focused on enhancing cellular resilience to cope with toxic protein species

- Interventions targeting shared pathways such as energy metabolism, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation that indirectly influence cytoskeletal health

- Gene-based therapies designed to correct specific genetic defects affecting cytoskeletal proteins

These approaches recognize that cytoskeletal defects do not occur in isolation but rather interact with other hallmark pathological processes in neurodegeneration, including protein aggregation, synaptic dysfunction, and inflammatory responses [16] [11].

Diagram 2: Pathogenic cascade linking cytoskeletal defects to neurodegeneration.

Cytoskeletal defects represent a fundamental pathological hallmark shared across diverse neurodegenerative disorders, contributing directly to clinical symptomatology through disrupted axonal transport, synaptic failure, and loss of structural integrity. The integrated view of cytoskeletal pathology presented in this review highlights common mechanisms while acknowledging disease-specific variations. As research in this field advances, several promising directions emerge:

First, the development of increasingly sophisticated tools for visualizing and manipulating cytoskeletal dynamics in live cells and intact organisms will continue to provide deeper insights into pathological mechanisms. Second, the identification of cytoskeletal biomarkers - particularly neurofilament proteins in biofluids - offers potential for improved diagnosis and tracking of disease progression [3]. Third, therapeutic strategies that target cytoskeletal defects as part of a comprehensive, multi-target approach hold promise for effectively modifying disease progression across multiple neurodegenerative conditions.

Ultimately, recognizing cytoskeletal defects as a unifying hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases reframes our conceptual approach to these disorders, emphasizing shared pathogenic mechanisms while acknowledging disease-specific variations. This perspective provides a robust framework for developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving neuronal structure and function in the face of neurodegenerative assault.

The neuronal cytoskeleton, composed of microtubules, neurofilaments, and actin filaments, serves as the structural foundation for axonal transport—a critical process that maintains neuronal health and function. Neurons are highly polarized cells with markedly compartmentalized structures, making them reliant on intricate transport systems to shuttle newly synthesized macromolecules and organelles from the cell body to distant synaptic terminals (anterograde transport) and to return signaling endosomes and autophagosomes for degradation (retrograde transport). This continuous bidirectional trafficking occurs along microtubule highways powered by molecular motor proteins: kinesins primarily mediate anterograde transport toward the synapse, while cytoplasmic dynein drives retrograde transport back to the cell body [18].

The proper functioning of axonal transport is fundamental to neuronal survival, as it ensures the appropriate distribution of essential components throughout the extensive axonal architecture. Disruption of this finely balanced system represents an early and critical event in the pathogenesis of multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and hereditary spastic paraplegia [18]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms underlying axonal transport failure, with particular emphasis on kinesin and dynein dysfunction within the broader context of cytoskeletal defects in neurodegeneration.

Molecular Mechanisms of Motor Protein Dysfunction

Regulation of Motor Protein Function and Cargo Binding

Motor proteins do not function in isolation; their activity is precisely regulated through interactions with binding partners, adaptor proteins, and post-translational modifications. Recent research has identified kinesin-binding protein as a key regulator of CHMP2B, a core component of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) pathway. This regulation is crucial for the processive movement and presynaptic localization of CHMP2B, which facilitates endolysosomal protein degradation at synapses. The frontotemporal dementia-causative CHMP2Bintron5 mutation exhibits deficient binding to kinesin-binding protein, resulting in impaired axonal transport characterized by little processive movement and oscillatory behavior of transport vesicles—a phenotype reminiscent of a tug-of-war between kinesin and dynein motor proteins [19].

The annexin family of calcium-binding proteins provides another layer of motor protein regulation. Annexin A7 (ANXA7) enhances the axonal trafficking of TIA1, an RNA-binding protein that forms ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules. This process is calcium-dependent, with calcium overload inducing phase separation of ANXA7-TIA1 complexes and consequently halting their transport. This mechanism is particularly relevant for ALS, where TIA1 mutations are associated with pathological protein aggregation. ANXA7 serves as a molecular bridge connecting TIA1-containing RNPs to dynein, facilitating their retrograde transport from axonal terminals to the cell body. Disruption of this system leads to TIA1 granule accumulation in axons and subsequent neurodegeneration [20].

Cytoskeletal Defects and Motor Protein Impairment

The integrity of microtubule networks is essential for efficient axonal transport, and modifications to tubulin or microtubule-associated proteins can severely disrupt motor protein function. In ALS, evidence suggests that tubulin nitration near the dynactin binding site may destabilize microtubule tracts and interfere with dynein motor function [21]. This nitration occurs through peroxynitrite formation, which modifies tyrosine residues on the aromatic ring. Since superoxide dismutase (SOD) normally prevents peroxynitrite formation, SOD1 mutations in familial ALS may promote tubulin nitration, creating a direct link between oxidative stress and transport defects along microtubules [21].

Tau, a microtubule-associated protein, plays a critical role in stabilizing microtubules and regulating motor protein function. In AD and other tauopathies, hyperphosphorylated tau exhibits reduced binding affinity to microtubules, potentially destabilizing them. However, hyperphosphorylated tau alone does not form fibrils unless sulphated aminoglycans such as heparin sulfate are present, suggesting that microtubule modifications may facilitate pathological fibril formation [21]. The specific tau isoforms also influence transport efficiency; mutations that increase the ratio of four-repeat to three-repeat tau isoforms enhance microtubule binding strength and aggregation propensity, further impairing axonal transport [21].

Table 1: Motor Protein Dysfunctions in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Motor Protein Affected | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontotemporal Dementia (linked to CHMP2Bintron5) | Kinesin | Deficient binding to kinesin-binding protein | Loss of processive movement, oscillatory transport vesicles, impaired presynaptic localization |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | Dynein | Tubulin nitration near dynactin binding site | Impaired retrograde transport, organelle accumulation |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Kinesin and Dynein | Hyperphosphorylated tau destabilizing microtubules | Reduced microtubule stability, impaired bidirectional transport |

| ALS/FTD (linked to TIA1 mutations) | Dynein | Disrupted ANXA7-TIA1-dynein complex in calcium overload | Defective RNP granule transport, pathological aggregation in axons |

Axonal Transport Deficits in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Alzheimer's Disease and Tauopathies

In Alzheimer's disease, the relationship between cytoskeletal defects and axonal transport disruption represents a core pathological mechanism. While amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin mutations influence the production and accumulation of amyloid-β peptides, neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau are more closely correlated with cognitive decline. Tau normally stabilizes microtubules, but when hyperphosphorylated, it dissociates from microtubules and aggregates into paired helical filaments. This loss of functional tau decreases microtubule stability, while the accumulated tau aggregates may physically impede motor protein progression along axons [21].

The significance of tau-mediated transport disruption extends beyond AD to a class of disorders collectively known as tauopathies, which include frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and Pick's disease. In FTDP-17, mutations in the tau gene directly cause disease, with some mutations altering the ratio of three-repeat to four-repeat tau isoforms and others affecting tau's binding affinity to microtubules [22]. These changes not only impair microtubule stability but also influence the motility of both kinesin and dynein motors, ultimately disrupting the balanced bidirectional transport essential for neuronal function.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Related Disorders

ALS exemplifies the devastating consequences of disrupted axonal transport on motor neuron survival. Multiple pathways converge to impair motor protein function in this disease. Mutations in SOD1, present in approximately 2% of familial ALS cases, were initially thought to cause disease through loss of antioxidant function. However, SOD1 null mice do not develop ALS-like pathology, suggesting a toxic gain-of-function mechanism instead [21]. Mutant SOD1 promotes protein aggregation that sequesters essential motor proteins and transport components, leading to measurable slowing of axonal transport in motor neurons—an early event in ALS pathophysiology [21].

The critical role of axonal transport in ALS is further highlighted by recent discoveries concerning RNA-binding proteins. In ALS and frontotemporal dementia, TIA1 protein mutations promote pathological phase separation and aggregation, disrupting the transport of mRNA granules in axons. The calcium-regulated mechanism of Annexin A7 in mediating TIA1-RNP transport via dynein provides a compelling link between calcium signaling defects and impaired axonal transport in neurodegeneration. When this transport fails, TIA1 granules accumulate in axons, forming pathological aggregates that trigger degenerative processes [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of Axonal Transport Defects in Neurodegeneration

| Experimental Model | Transport Parameter Measured | Change in Disease State | Technical Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHMP2Bintron5 mutant neurons | Processive movement | Drastic reduction | Live-cell imaging of fluorescently tagged CHMP2B |

| CHMP2Bintron5 mutant neurons | Vesicle dynamics | Increased oscillatory behavior ("tug-of-war") | Kymograph analysis of vesicle movements |

| ANXA7-deficient neurons | Retrograde transport velocity | Decreased by >50% | Live imaging of TIA1-RNP granules in axons |

| SOD1 mutant models | Axonal transport rate | Significant slowing | Radiolabeled protein tracking in motor neurons |

| Hyperphosphorylated tau models | Mitochondrial transport | Reduced velocity and increased pausing | Live imaging of mito-GFP in axons |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Live Imaging of Axonal Transport

The direct observation of cargo movement in living neurons has revolutionized our understanding of axonal transport dynamics. Current methodologies employ high-resolution live-cell imaging to track fluorescently labeled organelles, vesicles, or protein complexes in real-time. For investigating CHMP2B transport, researchers typically culture hippocampal or cortical neurons from rodent models, transfect them with fluorescent protein-tagged CHMP2B constructs (both wild-type and mutant forms), and conduct time-lapse imaging using spinning disk or TIRF microscopy. The resulting videos are analyzed with kymograph tools to quantify transport parameters including velocity, processivity, run length, and directionality. This approach revealed that while wild-type CHMP2B exhibits robust activity-dependent transport to presynaptic boutons, the CHMP2Bintron5 mutant displays minimal directed movement with increased oscillatory behavior [19].

For studying RNP granule transport, as in the ANXA7-TIA1 mechanism, researchers use microfluidic chambers to physically isolate axons from cell bodies, enabling clear observation of axonal transport without interference from somatic processes. Neurons are transfected with fluorescently tagged TIA1, and RNP movement is tracked before and after calcium influx induction. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) can further assess granule dynamics and phase separation properties. Through these methods, researchers determined that ANXA7 knockdown reduces retrograde transport velocity of TIA1 granules by over 50%, while ANXA7 overexpression can rescue transport defects caused by disease-associated TIA1 mutations [20].

Biochemical and Molecular Analyses

Complementary biochemical approaches are essential for elucidating the molecular interactions underlying transport defects. Co-immunoprecipitation assays demonstrate physical interactions between motor proteins and their cargo adapters. For example, immunoprecipitation of ANXA7 from neuronal lysates followed by mass spectrometry identification of binding partners established its role as a molecular bridge between TIA1 and the dynein motor complex [20]. Similarly, comparative co-immunoprecipitation of wild-type versus mutant CHMP2B with kinesin-binding protein confirmed the deficient interaction in the disease-associated variant [19].

Proximity ligation assays (PLA) provide spatial information about protein interactions within cellular contexts, revealing disrupted molecular proximities in disease states. In vitro microtubule binding and motility assays using purified components allow researchers to dissect the direct effects of pathogenic proteins on motor function, isolating these mechanisms from broader cellular influences. These reductionist approaches have been instrumental in demonstrating how mutant SOD1 directly impairs kinesin motility on microtubules and how hyperphosphorylated tau creates physical barriers to motor protein movement.

Figure 1: Experimental Approaches for Studying Axonal Transport Mechanisms. This workflow integrates live imaging, biochemical assays, genetic manipulation, and animal models to comprehensively investigate motor protein dysfunction in neurodegeneration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Axonal Transport Defects

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent protein tags | GFP-, RFP-, mCherry-tagged CHMP2B | Live imaging of ESCRT component transport | Visualizing and quantifying processive movement and synaptic recruitment |

| Microfluidic chambers | Compartmentalized neuronal culture chips | Isolation of axons for transport studies | Analyzing directional transport without somatic interference |

| Kymograph analysis software | ImageJ KymoToolBox | Quantification of vesicle dynamics | Measuring velocity, processivity, and directionality of moving cargo |

| Site-directed mutagenesis kits | CHMP2Bintron5 mutation | Introducing disease-associated mutations | Modeling genetic forms of neurodegeneration |

| Calcium indicators | GCaMP, Fura-2 | Monitoring intracellular calcium dynamics | Linking calcium signaling to transport regulation |

| Motor protein inhibitors | Ciliobrevin D (dynein inhibitor) | Disrupting specific motor functions | Determining contribution of specific motors to transport defects |

| Proximity ligation assay | Duolink PLA | Detecting protein-protein interactions | Visualizing molecular complexes in situ |

| Gene manipulation vectors | shRNA for ANXA7 knockdown | Modulating expression of regulatory proteins | Establishing necessity of adaptor proteins for transport |

Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions

Targeting Motor Protein Regulation

Emerging therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases focus on restoring axonal transport by targeting motor protein regulation and function. One promising approach involves enhancing the connectivity between motor proteins and their cargo. In the case of CHMP2Bintron5-related neurodegeneration, strategies that strengthen the interaction between mutant CHMP2B and kinesin-binding protein could potentially restore its axonal transport and presynaptic localization [19]. Similarly, modulating the ANXA7-TIA1-dynein interaction presents a therapeutic opportunity for ALS, particularly since ANXA7 overexpression has been shown to rescue TIA1 transport defects and reverse pathology in model systems [20].

Small molecule compounds that enhance kinesin or dynein processivity represent another innovative approach. These compounds could increase the run length of motor proteins, helping them overcome partial transport barriers formed by protein aggregates or cytoskeletal abnormalities. Additionally, compounds that regulate the phosphorylation state of motor proteins or their adaptors may optimize transport efficiency. For instance, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) inhibitors can reduce pathological tau phosphorylation, thereby improving microtubule stability and motor protein function—a strategy being explored for Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies.

Integrated Therapeutic Strategies

Given the complex, multifactorial nature of axonal transport breakdown, effective treatments will likely require integrated approaches that address multiple pathological mechanisms simultaneously. Gene therapy strategies that deliver neuroprotective factors like ANXA7 or functional versions of disease-associated genes offer promising avenues for inherited neurodegenerative conditions [20]. Meanwhile, approaches that enhance cellular protein clearance mechanisms, such as the ESCRT pathway whose components depend on proper axonal transport, may help reduce the burden of pathological protein aggregates [19].

The development of these targeted therapies depends on continued advances in understanding the basic biology of axonal transport and its regulation. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular interactions between motor proteins, their adaptors, and cargoes; mapping the signaling pathways that regulate these interactions in response to neuronal activity and stress; and identifying how disease-associated mutations specifically disrupt these processes. Such insights will enable the rational design of therapeutics that can restore axonal transport in a precise and disease-specific manner.

Figure 2: Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Axonal Transport Breakdown. Multiple intervention points exist for restoring axonal transport, including direct enhancement of motor protein function, stabilization of the cytoskeleton, and correction of cargo mislocalization through genetic and pharmacological approaches.

The investigation of axonal transport breakdown represents a crucial frontier in understanding and treating neurodegenerative diseases. As research continues to unravel the intricate relationships between kinesin, dynein, cytoskeletal elements, and disease-associated proteins, new opportunities for therapeutic intervention will emerge. By targeting the fundamental mechanisms of motor protein dysfunction within the broader context of cytoskeletal defects, researchers and drug development professionals can work toward effective treatments that address the root causes of neurodegeneration rather than merely alleviating symptoms.

The neuronal cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of microtubules, neurofilaments, and actin microfilaments, serves as the fundamental architectural and functional backbone of the neuron. This tripartite system maintains structural integrity, enables morphological plasticity, and facilitates essential processes including axonal transport, synaptic function, and intracellular signaling [23] [24] [25]. Microtubules, composed of α/β-tubulin heterodimers, provide polarized tracks for the active transport of vesicles, organelles, and proteins [24] [25]. Neurofilaments, as intermediate filaments, confer mechanical strength and regulate axonal caliber [24]. Actin microfilaments govern synaptic remodeling and dendritic spine dynamics through continuous assembly and disassembly [24]. The precise regulation of this cytoskeletal network is critical for neuronal homeostasis, and its progressive collapse is a central event in neurodegenerative pathogenesis [23] [24].

This review examines the pathological interplay between key aggregating proteins—tau and α-synuclein—and the cytoskeletal framework, positioning cytoskeletal defects as a critical mechanistic nexus in neurodegeneration. We explore how the functional impairment of tau, a microtubule-associated protein, and α-synuclein, a presynaptic protein, triggers a "dying back" pattern of degeneration that begins at the vulnerable synaptic terminals and progresses along the axon [26]. The synergistic relationship between these proteinopathies, their co-aggregation, and their combined disruptive effects on cytoskeletal integrity represent a compelling paradigm for understanding disease progression in conditions like Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and other related dementias [26] [27] [28].

Molecular Physiology of Cytoskeletal-Associated Proteins

Tau: Architect of Microtubule Stability

Tau is an intrinsically disordered microtubule-associated protein (MAP) predominantly expressed in neurons, where it plays a pivotal role in stabilizing microtubules and regulating axonal transport [26] [24]. The MAPT gene on chromosome 17 undergoes complex alternative splicing to generate six major isoforms in the human central nervous system [26] [24]. These isoforms differ by the inclusion of 0, 1, or 2 N-terminal inserts (0N, 1N, 2N) and either three or four microtubule-binding repeats (3R, 4R), resulting in proteins ranging from 352 to 441 amino acids [26] [24]. The 4R tau isoforms exhibit greater microtubule-binding affinity compared to 3R isoforms, and their balanced expression is crucial for neuronal health [26]. During development, a transition occurs where fetal brain expresses only the shortest 0N3R isoform, while adult brain maintains a nearly equal ratio of 3R and 4R isoforms, with regional variations in distribution [26] [24].

In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), tau transcript incorporates an additional exon, 4a, generating a high molecular weight isoform termed "Big tau" [26]. This isoform, with its elongated N-terminal domain, is believed to provide enhanced structural stability to long peripheral axons subject to significant mechanical stress and to facilitate the high rates of axonal transport characteristic of these neurons [26]. Its unique structure may also confer reduced propensity for pathological aggregation [26].

Table 1: Major Tau Isoforms in the Human Nervous System

| Isoform Name | N-Terminal Inserts | Microtubule-Binding Repeats | Primary Expression Context | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0N3R | 0 | 3 | Fetal Brain, Adult CNS | Shortest isoform; developmental regulation |

| 1N3R | 1 | 3 | Adult CNS | --- |

| 2N3R | 2 | 3 | Adult CNS | --- |

| 0N4R | 0 | 4 | Adult CNS | Higher microtubule affinity |

| 1N4R | 1 | 4 | Adult CNS | Higher microtubule affinity |

| 2N4R | 2 | 4 | Adult CNS | Higher microtubule affinity; less abundant |

| Big Tau | Extended (Exon 4a) | 4 | Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) | Enhanced mechanical stability |

Beyond its canonical role in microtubule stabilization, tau participates in other cellular processes. It can regulate axonal transport by influencing the attachment and detachment of motor proteins like kinesin and dynein [26]. Tau also localizes to pre- and post-synaptic structures and the nucleus, suggesting additional non-microtubule-related functions [26]. Under physiological conditions, tau's intrinsically disordered nature allows it to adopt a "paperclip" conformation, where its N- and C-termini interact with the mid-domain, a state modulated by post-translational modifications [26].

α-Synuclein: A Multifunctional Synaptic Regulator

Alpha-synuclein (α-syn) is a 140-amino-acid, natively unfolded protein highly enriched at presynaptic terminals [29] [27]. Its primary physiological functions center on synaptic vesicle trafficking, neurotransmitter release, and the maintenance of synaptic vesicle pools [27]. α-Syn interacts with synaptic vesicles to promote their clustering and modulates the assembly of the SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complex, which is essential for synaptic vesicle exocytosis [27]. This role in facilitating efficient synaptic transmission underscores its importance in neuronal communication. Furthermore, α-syn's ability to bind lipids allows it to participate in regulating membrane curvature and lipid metabolism [27].

Neurofilaments: The Structural Scaffold

Neurofilaments are the intermediate filaments of neurons, forming a stable, flexible network that provides crucial structural support and determines axonal caliber [24]. Composed of polypeptide subunits (NF-L, NF-M, NF-H), they assemble into heteropolymers that exhibit high tensile strength and resistance to mechanical stress [23] [24]. Unlike the highly dynamic microtubules and actin filaments, neurofilaments are more stable, forming a robust scaffold that maintains the structural integrity of elongated axons and facilitates the efficient conduction of electrical impulses [23] [24].

Pathological Transitions: From Functional Protein to Cytoskeletal Toxin

Tau Misfolding, Hyperphosphorylation, and Microtubule Dissociation

The pathological transformation of tau from a stabilizing MAP to a toxic entity is a multi-step process. A critical initiating event is its abnormal post-translational modification, particularly hyperphosphorylation [24] [25]. In Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other tauopathies, tau undergoes site-specific hyperphosphorylation within its microtubule-binding domain, reducing its affinity for microtubules and leading to its dissociation [24] [25]. This liberation of tau from microtubules has two catastrophic consequences: the destabilization of microtubule networks, which disrupts axonal transport, and the accumulation of free, phosphorylated tau in the cytosol [24] [25].

Once dissociated, hyperphosphorylated tau undergoes a conformational change, misfolding and self-assembling into toxic oligomers, which subsequently aggregate into larger, insoluble structures known as paired helical filaments (PHFs) and straight filaments (SFs) [29] [24]. These filaments are the primary constituents of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), a defining histopathological hallmark of AD [24]. The accumulation of tau pathology, as described by Braak staging, closely parallels the trajectory of cognitive decline and brain atrophy in AD, positioning it as a central executor of neurodegeneration [24] [25]. The prion-like propagation of pathological tau between cells further accelerates the spread of pathology throughout connected brain networks [24].

α-Synuclein Aggregation and Strain Heterogeneity

Similar to tau, α-synuclein is prone to pathological transformation. Under stress conditions or due to genetic mutations, natively unfolded α-syn monomers undergo a conformational shift, forming β-sheet-rich oligomers and ultimately progressing into insoluble fibrils [29] [27]. These aggregates are the primary components of Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites, the pathological hallmarks of PD and other synucleinopathies [27] [28]. A groundbreaking discovery in the field is the existence of distinct α-synuclein "strains"—structurally unique fibril polymorphs that are associated with different disease phenotypes and seeding properties [29].

Recent cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies have revealed a specific α-syn fibril polymorph, termed "strain B," which possesses a unique core structure that incorporates both the N- and C-termini of the protein (residues 14-22 and 105-115, respectively) [29]. This strain demonstrates a remarkable propensity to cross-seed and promote the aggregation of tau protein, both in neuronal cultures and in vitro, providing a structural basis for the co-occurrence of these pathologies [29]. The C-terminal domain of α-syn (residues 105-115) appears critical for this interaction, suggesting it presents a novel interface for direct interaction with tau [29].

Table 2: Characteristics of Pathological Alpha-Synuclein Strains

| Strain Feature | Strain A | Strain B |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Seeding Preference | α-Synuclein aggregation | Tau co-aggregation |

| Core Structure (Residues) | 38-97 | 14-22, 37-100, 105-115 |

| Fibril Core Size | Smaller, classic wild-type | Largest reported α-syn structure |

| Terminal Involvement | Not incorporated into core | N- and C-termini form part of ordered core |

| Biological Consequence | Traditional synucleinopathy | Mixed proteinopathy, promotes tau pathology |

Synergistic Toxicity: Cross-Seeding and Co-Aggregation

The interplay between tau and α-synuclein extends beyond mere coexistence; they engage in a synergistic relationship that exacerbates neurodegeneration. These proteins can directly interact and promote each other's aggregation through cross-seeding, where fibrils of one protein can act as a template to accelerate the misfolding and aggregation of the other [27] [28]. This cross-talk creates a deleterious feed-forward loop, significantly amplifying the burden of pathological aggregates beyond what either protein could achieve independently [28]. This synergy is a key feature of mixed dementias, such as Alzheimer's disease with Lewy bodies, and contributes to more rapid and aggressive disease progression [27] [28].

The molecular basis for this interaction is being unraveled. As mentioned, the unique structure of α-syn "strain B" facilitates tau aggregation [29]. Furthermore, the co-localization of tau and α-syn within the same cellular inclusions, such as Lewy bodies, has been consistently observed in post-mortem brain tissue, and mass spectrometry has identified tau as a component of LBs [27] [28]. This co-aggregation potentiates neurotoxicity by disrupting mutual physiological functions and overwhelming the cell's proteostatic clearance mechanisms, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway [27].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Protein-Cytoskeleton Interactions

Structural Elucidation of Pathological Aggregates

Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) for Atomic-Level Structural Determination

Cryo-EM has become an indispensable tool for determining the high-resolution structures of pathological protein aggregates, such as tau filaments and α-synuclein fibrils [29]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for structural determination of α-synuclein fibrils:

- Fibril Preparation and Purification: Recombinant α-synuclein is expressed and purified. Fibrillization is induced by incubating monomeric α-synuclein with constant agitation. Distinct strains (e.g., Strain A and B) can be generated through successive seeding generations [29].

- Grid Preparation and Vitrification: A purified fibril sample is applied to a cryo-EM grid (e.g., a holey carbon grid). Excess liquid is blotted away, and the grid is rapidly plunged into a cryogen (liquid ethane) to vitrify the sample, preserving its native state in a thin layer of amorphous ice [29].

- Data Collection: The vitrified grid is loaded into a high-end cryo-electron microscope (e.g., a 300 keV Titan Krios). Thousands of micrographs are collected automatically at a high magnification (e.g., 81,000x) under low-dose conditions to minimize radiation damage [29].

- Image Processing and Helical Reconstruction:

- Particle Picking: Fibril segments ("particles") are manually or automatically selected from the micrographs. For example, one study picked 46,626 fibril segments from 2,934 micrographs [29].

- 2D Classification: Particles are classified based on similar features to identify homogeneous groups and remove junk particles.

- Initial Model Generation and 3D Refinement: An initial 3D model is generated and used as a reference for iterative rounds of 3D classification and helical refinement using software suites like RELION. This yields a high-resolution 3D density map [29].

- Atomic Model Building and Refinement: An atomic model is built into the resolved density map using tools like Coot and refined against the map using programs like Phenix [29].

In Vitro Cross-Seeding Assays Using Thioflavin T (ThT) Fluorescence

Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assays are a standard method to quantitatively monitor the kinetics of protein aggregation and cross-seeding in real-time [29].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare purified monomeric proteins (e.g., tau 2N4R, α-synuclein). Pre-formed fibrils (PFFs) of the "seeding" protein are sonicated to generate short fragments.

- Assay Setup: In a quartz cuvette or multi-well plate, mix the monomeric "substrate" protein with ThT dye in a suitable buffer. For cross-seeding experiments, add PFFs of the "seeder" protein (e.g., α-syn Strain B) to the reaction. Include control groups with monomers alone and seeds alone.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Load the plate into a fluorescence plate reader. Set the excitation wavelength to ~440 nm and emission to ~480 nm. Incubate the reaction at 37°C with continuous shaking, taking fluorescence measurements at regular intervals.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity over time to generate aggregation kinetics curves. A characteristic sigmoidal curve is observed, with a lag phase (nucleation), growth phase (elongation), and plateau phase (saturation). Cross-seeding by an active strain (like α-syn Strain B) is indicated by a significant shortening of the lag phase and an increase in the final fluorescence intensity compared to controls [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Cytoskeletal Proteinopathies

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Formed Fibrils (PFFs) | Seeding agents to induce aggregation in cell/animal models. | Sonicated α-syn or tau fibrils; distinct strains (e.g., α-syn Strain B for tau cross-seeding). |

| Thioflavin T (ThT) | Fluorescent dye for monitoring aggregation kinetics. | Binds to β-sheet-rich structures; increased fluorescence indicates fibril formation. |

| Primary Neuronal Cultures | Physiologically relevant in vitro system for studying toxicity. | Mouse or rat cortical/hippocampal neurons; can be seeded with PFFs. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | High-resolution structural biology technique. | Determines atomic structures of fibrils (e.g., α-syn Strain B at 2.6 Å). |

| Transgenic Mouse Models | In vivo modeling of proteinopathy and cytoskeletal defects. | Express human mutant tau (e.g., P301L) or α-syn (e.g., A53T); model propagation. |

| Proteomics Platforms (SomaScan, Olink) | High-dimensional biomarker discovery in biofluids. | Measures ~7,000 proteins; identifies disease-specific signatures (GNPC consortium) [10]. |

Figure 1: Pathological Cascade of Tau and α-Synuclein Interaction. This diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between tau and α-synuclein in driving neurodegeneration. Initial pathological triggers lead to the misfolding of both proteins. Critically, specific α-synuclein strains can directly cross-seed tau aggregation, creating a feed-forward loop that leads to co-aggregation, cytoskeletal collapse, and eventual neuronal death.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Cytoskeletal Integrity and Protein Aggregation

The understanding of tau and α-synuclein interactions with the cytoskeleton opens multiple avenues for therapeutic intervention. One strategic approach is to directly stabilize the microtubule network. Microtubule stabilizers, such as those used in cancer therapy (e.g., taxanes), or brain-penetrant derivatives like TPI-287, have been explored in clinical trials for AD and related tauopathies [23]. These compounds aim to compensate for the loss of stabilizing function caused by tau dissociation, thereby restoring axonal transport and neuronal health [23] [24].