Cytoskeletal Blueprint of Invasion: Decoding Architectural Cues in Cancer Cells for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advancements

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct cytoskeletal architectures that differentiate invasive from non-invasive cancer cells, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cytoskeletal Blueprint of Invasion: Decoding Architectural Cues in Cancer Cells for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advancements

Abstract

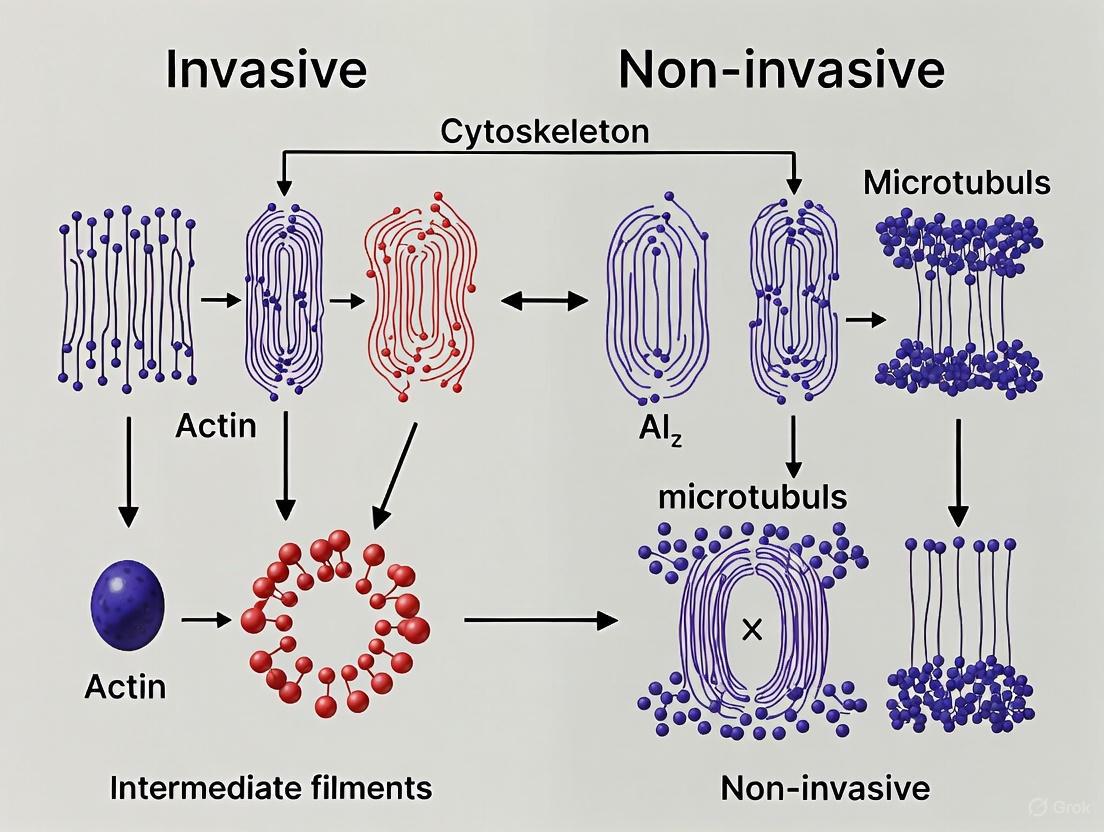

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct cytoskeletal architectures that differentiate invasive from non-invasive cancer cells, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational role of cytoskeletal dynamics in cell invasion, evaluates advanced computational and live-cell imaging methodologies for quantitative analysis, addresses key technical challenges in assay systems, and validates cytoskeletal targets for therapeutic intervention. By synthesizing recent findings on microtubule organization, actin dynamics, and cytoskeletal crosslinkers like plectin, this review establishes the cytoskeleton as a critical biomarker and a promising target for anti-metastatic strategies, offering a roadmap for future biomedical and clinical research.

Architectural Hallmarks: How Cytoskeletal Reorganization Drives the Invasive Phenotype

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, three-dimensional network essential for maintaining cellular architecture and enabling critical processes such as cell division, migration, and invasion [1]. During cancer progression, cells undergo profound morphological transformations, and the reorganization of the cytoskeleton, particularly microtubules, is known to play a key role [1]. Microtubules, composed of α-/β-tubulin heterodimers, are not merely structural elements; their precise organization—including their quantity, orientation, compactness, and radiality—creates identifiable signatures that can distinguish invasive from non-invasive cellular phenotypes [1]. The ability to detect and quantify these subtle architectural alterations provides a powerful proxy for identifying aggressive cancer cells at an early stage, addressing a critical limitation in current diagnostic approaches [1]. This guide objectively compares the microtubule signatures associated with invasive potential, summarizing key experimental data and providing the methodological toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals to apply these findings in their work.

Quantitative Comparison of Microtubule Signatures

The architectural features of microtubules undergo distinct reorganization in cells with invasive potential. The quantitative differences outlined in the table below provide a signature profile for identifying such cells.

Table 1: Quantitative Microtubule Signatures in Non-Invasive vs. Invasive Cells

| Microtubule Feature | Non-Invasive Cell Signature | Invasive Cell Signature | Measurement Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Orientation | Higher Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) [1] | Lower OOP value, indicating disperse fiber orientations [1] | Measures global alignment of fibers; lower OOP signifies disorganization. |

| Fiber Length | Longer, more stable microtubules [1] | Shorter microtubules [1] | Indicates microtubule polymerization dynamics and stability. |

| Fiber Quantity (Nl) | Variable, dependent on cell state [1] | Variable, dependent on cell state [1] | The absolute number of polymerized microtubule fibers in a cell. |

| Fiber Compactness | Lower fiber density (e.g., 0.421 μmâ»Â²) [1] | Higher fiber density (e.g., 1.539-2.039 μmâ»Â²) [1] | Number of fibers per unit area (Nl/Ac); indicates spatial distribution. |

| Radiality (Radial Score) | Lower radial score (e.g., 0.266) [1] | Prominent radial pattern from nucleus (e.g., 0.564) [1] | Measures the extent to which fibers nucleate from the nucleus centroid. |

These signatures were validated in a model of cells expressing wild-type E-cadherin (non-invasive) versus a mutant E-cadherin that leads to loss of cell-cell adhesion and an invasive phenotype. The analysis confirmed that mutant, invasive cells exhibit significantly lower OOP values, corresponding to a more disorganized microtubule network [1].

Experimental Protocols for Microtubule Signature Analysis

Computational Pipeline for Cytoskeletal Architecture

A novel computational pipeline has been developed to dissect the cytoskeletal architecture of cancer cells with invasive potential from immunofluorescence images [1]. The following workflow details the key steps:

Table 2: Key Experimental Reagents and Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| α-Tubulin Antibody | Immunofluorescence staining to visualize the microtubule network. |

| Cell Culture with Laminin | Provides a supportive extracellular matrix environment for cell growth. |

| E-cadherin Mutant Model | A well-established cellular model (e.g., p.L13_L15del mutant) that leads to loss of cell-cell adhesion and an invasive phenotype for validation. |

| Deconvolution Software | Removes noise and blur from Z-stack images, improving contrast and resolution. |

| Gaussian, Sato, and Hessian Filters | Image processing filters used to smooth signals, highlight curvilinear structures, and generate binary images of fibers. |

Protocol Workflow:

- Sample Preparation and Imaging: Culture cells on an appropriate substrate like laminin. Perform immunofluorescence staining using an antibody against α-tubulin to label the microtubule network. Acquire high-resolution images using a fluorescence microscope, capturing multiple Z-slices for each field of view [1].

- Image Pre-processing: Apply deconvolution to the Z-stack images to reduce noise and enhance clarity. Perform a maximum intensity projection (MIP) to create a single 2D composite image from the Z-stack for analysis [1].

- Fiber Enhancement and Segmentation: Process the projected image with a Gaussian filter to smooth the fluorescence signal. Subsequently, apply a Sato filter, which is specifically designed to enhance curvilinear structures, making individual microtubule fibers more distinct. Finally, use a Hessian filter to generate a binary image, separating the fiber structures from the background [1].

- Skeletonization and Feature Extraction: Skeletonize the binary image to reduce each fiber to a single-pixel-wide line. This skeleton is then used for automatic extraction of two classes of features:

- Line Segment Features (LSFs): Treats the skeleton as a collection of line segments to quantify metrics like fiber length, orientation (OOP), and quantity (Nl) [1].

- Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNFs): Represents the skeleton as a graph network of nodes and edges to quantify connectivity, complexity, and radiality relative to the nucleus centroid [1].

- Data Analysis and Validation: Compare the extracted feature sets (e.g., OOP, compactness, radiality) between control (e.g., wild-type E-cadherin) and experimental (e.g., mutant E-cadherin) cell populations to identify statistically significant alterations associated with the invasive phenotype [1].

Directionality Analysis with TeDT

For a more focused analysis of microtubule orientation, the Texture Detection Technique (TeDT) provides a robust solution. This software tool is based on the Haralick texture method and quantifies directionality by considering both local and global image features, with greater weight on the latter [2]. It is particularly useful for complex microtubule patterns that are difficult to assess visually.

Protocol Workflow:

- Input: Use immunofluorescence images of microtubules.

- Analysis: Run the TeDT algorithm, which expresses results in a graphic form that is responsive to subtle variations in microtubule distribution.

- Output: A numerical score that allows for the quantitation of overall directionality, enabling direct comparison between cell states [2].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental and analytical processes described in this guide.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Diagram Title: Workflow for Automated Microtubule Feature Extraction

Microtubule Signature Feature Relationships

Diagram Title: Microtubule Signature Relationships in Invasive Cells

The actin cytoskeleton serves as a primary mechanical engine for cell motility, generating the protrusive and contractile forces necessary for cellular movement. In pathological contexts such as cancer metastasis, the dysregulation of actin dynamics is a critical factor driving the transition from a non-invasive to an invasive phenotype. Invasive cells exhibit distinct cytoskeletal architectures characterized by altered filament organization, dynamics, and mechanical properties compared to their non-invasive counterparts. These differences are not merely morphological but are fundamental to the enhanced migratory and force-generating capabilities of invasive cells. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the experimental frameworks and quantitative data used to dissect these differences, offering researchers a detailed overview of methodologies, key regulatory components, and analytical tools for studying actin-based motility.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Actin Architecture and Dynamics

Computational Pipeline for Cytoskeletal Feature Extraction

A novel bioimage analysis pipeline enables quantitative dissection of the cytoskeleton's spatial organization from standard immunofluorescence images. This method is particularly suited for comparing invasive and non-invasive cells [1].

- Sample Preparation and Imaging: Cells are cultured on appropriate substrates (e.g., laminin for a supportive environment), fixed, and stained for a cytoskeletal component such as α-tubulin (for microtubules) or phalloidin for F-actin. The nucleus is also stained. Multiple images are acquired for each channel along the Z-axis [1].

- Image Pre-processing: Z-stacks are projected into 2D using maximum intensity projection (MIP). Deconvolution is applied to remove noise and blur, improving contrast and resolution. A Gaussian filter is then used to smooth the fluorescence signal of cytoskeletal components [1].

- Fiber Segmentation and Skeletonization: A Sato filter is applied to highlight curvilinear structures, and a Hessian filter helps generate binary images. The binary images are then skeletonized, reducing the cytoskeletal network to single-pixel-wide lines for quantitative analysis [1].

- Feature Extraction: The skeletonized image is analyzed to extract two classes of features:

- Line Segment Features (LSFs): Describe the morphology and distribution of individual fibers, including parameters like length, orientation, and quantity [1].

- Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNFs): Describe the topological properties of the network using graph theory, quantifying connectivity, complexity, and radiality relative to the nucleus centroid [1].

- Application Note: This pipeline was validated using cells expressing wild-type E-cadherin versus a mutant E-cadherin (p.L13_L15del) that causes loss of cell-cell adhesion and increases invasiveness. The method successfully distinguished unique microtubule signatures between the two cell types [1].

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) for Actin Turnover

FRAP is used to measure the dynamics and turnover of actin filaments, differentiating between populations of stable and dynamic actin [3].

- Cell Preparation: Neurons or other cell types expressing a fluorescently tagged actin (e.g., GFP-Actin) are used. The cells should be in a mature state (e.g., 14 days in vitro for neurons) [3].

- Photobleaching and Recovery: A specific region of interest within a cellular structure, such as a dendritic spine, is bleached using a high-intensity laser beam, permanently disabling the fluorescence of the tagged proteins in that area. The laser is then switched back to a low-intensity setting to monitor the fluorescence recovery over time [3].

- Data Analysis: The recovery kinetics are quantified. The mobile fraction of actin and the half-time of recovery provide information on actin turnover rates. A persistent, non-recovering fraction indicates a stable pool of actin that does not exchange rapidly with the surrounding cytoplasm. This stable pool is often associated with cross-linked filaments [3].

- Application Note: This protocol can reveal long-term changes in actin stability following stimuli. For instance, hours after the induction of chemical Long-Term Potentiation (cLTP), a 2-3 fold increase in the stable actin pool was observed in dendritic spines, which is crucial for maintaining structural changes [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Cytoskeletal Features

The following tables summarize key quantitative differences in cytoskeletal organization and the effects of various perturbations, as identified through the described methodologies.

Table 1: Quantitative Cytoskeletal Features in Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Cells

| Parameter | Description | Non-Invasive Cells (Wild-Type E-cadherin) | Invasive Cells (Mutant E-cadherin) | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) | Measures fiber alignment; higher value = more aligned fibers. | Higher OOP values | Significantly lower OOP values [1] | Computational Pipeline [1] |

| Fiber Compactness (Nl/Ac) | Number of fibers per unit cell area. | Less compact, more dispersed fibers (e.g., 0.421 μmâ»Â²) [1] | More compactly distributed fibers (e.g., 1.539-2.039 μmâ»Â²) [1] | Computational Pipeline [1] |

| Fiber Length Variability | Intercellular variability in the length of fibers. | Lower variability | Higher variability [1] | Computational Pipeline [1] |

| Radiality Score (RS) | Measures how much fibers nucleate from the nucleus centroid. | Variable, but can be low in round cells (e.g., 0.266) [1] | Can show a more prominent radial pattern (e.g., 0.564) [1] | Computational Pipeline [1] |

Table 2: Effects of Genetic and Pharmacological Perturbations on Actin Dynamics

| Perturbation / Condition | Biological Context | Key Observed Effects on Cytoskeleton & Motility | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cofilin Deficiency | T cell development | Severe early block in thymocyte development; accumulated F-actin, impaired migration and synapse disassembly [4]. | Genetic mouse model (Cfl1 mutation) [4] |

| WASP/ARPC1B Mutation | Immunodeficiency (WAS) | Defective branched actin polymerization; aberrant actin spikes/filopodia; unstable cell conjugates and impaired cytotoxicity [4]. | Patient T cells [4] |

| ATM-3507 (Tpm3.1/3.2 inhibitor) | B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | Disrupted peripheral actin ring and actomyosin arcs; inhibited BCR-induced spreading, growth, and chemotaxis [5]. | DLBCL cell lines [5] |

| Non-Invasive Physical Plasma (NIPP) | Various Cancer Cell Lines | Disrupted cytoskeletal organization; altered metabolic activity; inhibited proliferation and migration [6]. | Ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer cell lines [6] |

| Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) | Neuronal Dendritic Spines | Rapid spine volume increase (~150%); long-term (hours) 2-3 fold increase in the stable, cross-linked actin pool [3]. | Hippocampal cultured neurons [3] |

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Actin Regulators in Protrusion and Motility

The core machinery for generating protrusive forces involves a coordinated system of nucleators, binding proteins, and small GTPases. The Arp2/3 complex, activated by Nucleation-Promoting Factors (NPFs) like WASP and WAVE2, generates branched actin networks that drive lamellipodial protrusions at the leading edge. Simultaneously, formin proteins (e.g., mDia1) generate linear actin filaments and arcs, which cooperate with myosin II to contract and transport cargo inward [4]. The balance between polymerization and depolymerization is fine-tuned by proteins like cofilin, which severs old filaments to replenish the monomer pool [4]. In motile cells such as lymphocytes, this machinery is polarized to form an immunological synapse, with continuous retrograde actin flow corralling receptors and stabilizing contact with target cells [4].

Diagram Title: Actin Regulatory Network for Motility

Force Generation and Mechanosensing by Myosin Filaments

Myosin II is the primary motor protein generating contractile forces. It self-assembles into bipolar filaments that walk toward the barbed ends of actin filaments. The structural properties of these filaments—including the number of myosin heads, the length of the filament, and the size of the central bare zone—directly impact the magnitude and efficiency of force generation [7]. In disorganized actomyosin networks, myosin II filaments generate tensile forces by pulling anti-parallel actin filaments together, while compressive forces are dissipated through filament buckling. Computational models show that cooperative effects between multiple myosin filaments can enhance total force output, and the presence of passive actin cross-linkers can stabilize the network against these forces [7]. This contractile apparatus is essential for processes like cytokinesis, focal adhesion turnover, and the retrograde flow of actin at the immunological synapse.

Actin Repair by Force-Activated Zyxin

The cytoskeleton is subject to mechanical stress and damage. The LIM-domain protein zyxin acts as a force-sensitive sensor that localizes to sites of actin filament rupture. Upon damage, zyxin forms force-dependent assemblies that bridge broken filament fragments. These assemblies then serve as a platform to recruit and coordinate repair factors: they recruit VASP to nucleate new actin filaments and α-actinin to crosslink them into aligned bundles, thereby rapidly restoring the integrity of the stress fiber [8]. This mechanism operates at the network scale to maintain cytoskeletal integrity under mechanical load.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Actin Dynamics and Motility

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ATM-3507 (Anisina) | Selective inhibitor of Tpm3.1/3.2 tropomyosin isoforms [5]. | Disrupts Tpm3.1/3.2-stabilized actin filaments; used to study roles in B-cell spreading, lymphoma growth, and migration [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Targeted gene knockout or mutation. | Generating deficient cell lines (e.g., cofilin, WASP, ARPC1B) to study protein function in actin polymerization and T cell function [4]. |

| Reconstituted Systems | Purified proteins (actin, NPFs, Arp2/3, etc.) assembled in vitro [9]. | Minimal system to study actin network assembly, force generation, and interaction with membranes or beads, free from cellular complexity [9] [8]. |

| Agent-Based Computational Models | In silico simulation of actomyosin structures [7]. | Modeling force generation by myosin II filaments with detailed structural properties in bundles and networks [7]. |

| Non-Invasive Physical Plasma (NIPP) | Induces oxidative stress and metabolic disruption [6]. | Modulates cancer cell cytoskeleton, growth, and motility without inducing cytoprotective heat shock proteins [6]. |

| Flt3-IN-6 | Flt3-IN-6, MF:C23H25N5O3, MW:419.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser TFA | Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser TFA, MF:C19H31F3N8O11, MW:604.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Computational Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key steps in the computational pipeline for quantifying cytoskeletal architecture, providing a clear workflow for researchers looking to implement this approach.

Diagram Title: Cytoskeletal Analysis Computational Pipeline

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network critical for maintaining cellular architecture and function. Its three major components—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—do not operate in isolation but are functionally integrated by specialized proteins known as cytoskeletal crosslinkers. Among these, plectin stands out as a versatile and crucial cytolinker that facilitates cytoskeletal crosstalk and mechanotransduction. This review synthesizes current research comparing cytoskeletal organization in invasive and non-invasive cells, with a focused analysis on plectin's role as a master integrator of mechanical signaling. We examine how plectin-mediated networks differ between these cellular states and evaluate emerging therapeutic strategies that target this crosslinking functionality, providing a comparative guide grounded in experimental data.

Plectin: A Master Cytoskeletal Integrator

Plectin is a giant (~500 kDa) cytolinker protein encoded by the PLEC gene, located on chromosome 8 (8q24) [10]. Its structural organization includes an N-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD), a central plakin domain, a rod domain, and a C-terminal intermediate filament-binding domain [10]. This multidomain architecture enables plectin to crosslink all three major cytoskeletal filament systems: actin filaments, intermediate filaments (particularly vimentin), and microtubules [10]. Through alternative splicing of its first exons, plectin generates multiple isoforms that target distinct cellular structures, including plectin 1a (hemidesmosomes), 1b (mitochondria), 1c (microtubules), and 1f (focal adhesions) [10].

Plectin's crosslinking activity is mechanosensitive, responding to actomyosin contractility and substrate stiffness [11]. This property positions plectin as a key regulator of cellular tensional homeostasis, enabling cells to sense and respond to mechanical cues from their extracellular environment [12] [13]. In migrating cells, plectin facilitates the interaction between F-actin and vimentin intermediate filaments in an actomyosin-dependent manner, creating integrated networks that withstand mechanical stress during cell movement [11].

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Cytoskeletal Organization

Methodologies for Assessing Cytoskeletal Crosstalk

Investigating plectin-mediated cytoskeletal integration requires specialized experimental approaches that can capture both structural organization and dynamic interactions:

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA): This technique generates fluorescent signals when antibodies bound to target proteins are within 40 nm, allowing precise detection of protein-protein interactions. Researchers have employed PLA to demonstrate plectin-dependent crosslinking between actin and vimentin networks, with significant reduction in PLA puncta observed following plectin knockdown [11].

Intermolecular FRET Imaging: Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between fluorophore-tagged cytoskeletal components (e.g., mTurquoise-actin and mNeongreen-vimentin) confirms their close molecular interactions in live cells migrating through 3D environments. This approach has revealed that actin-vimentin interactions are partially dependent on ROCK-mediated actomyosin contractility [11].

Computational Cytoskeletal Analysis: Novel image-based pipelines enable quantitative characterization of cytoskeletal architecture from immunofluorescence images. This methodology involves deconvolution, Gaussian and Sato filtering, Hessian analysis, and skeletonization to extract parameters including fiber orientation, morphology, compactness, and radiality relative to the nucleus [1].

Genetic and Pharmacological Perturbation: Plectin function can be disrupted using siRNA-mediated knockdown (achieving ~62% reduction in expression) [11], CRISPR/Cas9-generated knockout cells [12] [13], and the ruthenium-based inhibitor plecstatin-1 (PST) [12] [13]. These approaches enable comparative analysis of cytoskeletal organization and cell behavior with and without functional plectin.

Workflow for Cytoskeletal Architecture Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for analyzing cytoskeletal organization in invasive and non-invasive cells:

Comparative Cytoskeletal Architecture: Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Cells

Quantitative Differences in Cytoskeletal Organization

Computational analysis of cytoskeletal architecture reveals distinct organizational patterns between invasive and non-invasive cells. The table below summarizes key differences identified through quantitative imaging:

Table 1: Cytoskeletal Features in Invasive Versus Non-Invasive Cells

| Cytoskeletal Feature | Non-Invasive Cells | Invasive Cells | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microtubule Orientation | Higher OOP values (0.475) indicating aligned fibers | Lower OOP values (0.019) indicating disorganized fibers | Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) [1] |

| Microtubule Length | Variable | Shorter fibers with higher length variability | Line Segment Extraction (LiE) [1] |

| Fiber Compactness | More dispersed distribution (0.421 μmâ»Â²) | More compact distribution (2.039 μmâ»Â²) | Fibers per cell area (Nl/Ac) [1] |

| Radial Organization | Lower radial scores (0.266) | Higher radial scores (0.564) | Radiality Score (RS) [1] |

| Fiber-Nucleus Distance | Shorter distances (3.14 μm) | Longer distances (15.94 μm) | Distance to nucleus centroid (Di) [1] |

| Actin-Vimentin Interaction | Plectin-dependent, mechanosensitive | Enhanced, contractility-dependent | Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) [11] |

Plectin Expression and Localization Patterns

Plectin demonstrates distinct expression and subcellular localization patterns that correlate with invasive potential:

Table 2: Plectin Dysregulation in Cancer Cells

| Aspect of Dysregulation | Non-Invasive/Well-Differentiated Cells | Invasive/Poorly-Differentiated Cells | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Lower plectin expression | Elevated plectin levels (HCC, pancreatic, ovarian cancer) [12] [10] | Promoted migration, invasion, and metastasis [12] [13] |

| Subcellular Localization | Cytoplasmic distribution | Perimembranous enrichment; cell surface presentation (CSP) [12] [10] | Enhanced mechanosignaling; novel functions in migration [12] [10] |

| Isoform Expression | Balanced isoform profile | Isoform-specific dysregulation (e.g., plectin 1f in focal adhesions) [10] | Targeted cytoskeletal remodeling at specific locations [10] |

| Prognostic Value | Not applicable | Correlates with poor survival and decreased recurrence-free survival in HCC [12] [13] | Potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarker [12] [13] |

Plectin in Mechanosignaling and 3D Cell Migration

Mechanisms of Plectin-Mediated Mechanotransduction

In invasive cells, plectin integrates mechanical signals from the extracellular matrix through focal adhesions, activating key oncogenic signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates plectin's role in mechanotransduction:

Plectin inactivation through genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition with plecstatin-1 disrupts this mechanical signaling cascade, attenuating FAK, MAPK/Erk, and PI3K/AKT pathway activation and consequently suppressing tumor growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma models [12] [13] [14].

Role in 3D Migration and Nuclear Piston Mechanism

Plectin facilitates a "nuclear piston" migration mechanism essential for invasive movement through 3D matrices. This process involves:

Cytoskeletal Polarization: Plectin crosslinks vimentin and actomyosin filaments, localizing the vimentin network around the nucleus and polarizing non-muscle myosin II (NMII) anterior to the nucleus [11].

Nuclear Translocation: Plectin-mediated connections between the vimentin network and actomyosin filaments enable forward pulling of the nucleus as cells migrate through confined 3D spaces [11].

Pressure Compartmentalization: The nucleus acts as a piston, generating compartmentalized intracellular pressure with high-pressure anterior cytoplasmic compartments and lower-pressure rear compartments, facilitating lobopodial protrusions [11].

Mechanosensitive Regulation: Plectin-vimentin interactions are mechanosensitive, responding to NMII contractility and substrate stiffness to activate the nuclear piston machinery specifically in cross-linked 3D environments [11].

Plectin knockdown disrupts these processes, impairing 3D migration without significantly affecting 2D movement, highlighting its specific role in invasive migration through complex microenvironments [11].

Therapeutic Targeting of Plectin-Mediated Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions for Plectin Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Plectin Function

| Reagent/Technique | Specific Example | Research Application | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA Knockdown | Pan-plectin siRNA | Reduces plectin expression by ~62% [11] | Decreased actin-vimentin PLA puncta; impaired 3D migration [11] |

| Pharmacological Inhibitor | Plecstatin-1 (PST) | Ruthenium-based plectin inhibitor [12] [13] | Suppressed HCC growth, invasion, and metastasis in mouse models [12] [13] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout | PLEC-deficient HCC cells | Complete genetic ablation of plectin [12] [13] | Limited migration, invasion, and anchorage-independent growth [12] [13] |

| Proximity Ligation Assay | Actin-Vimentin PLA | Detects <40 nm interactions between cytoskeletal networks [11] | Quantified plectin-dependent cytoskeletal crosslinking [11] |

| FRET Imaging | mTurquoise-actin + mNeongreen-vimentin | Live-cell monitoring of cytoskeletal interactions [11] | Confirmed actomyosin-dependent actin-vimentin association [11] |

Emerging Therapeutic Applications

Targeting plectin-mediated cytoskeletal integration represents a promising therapeutic strategy for invasive cancers:

Plecstatin-1 in HCC: Treatment with PST inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma initiation and growth in autochthonous and orthotopic mouse models, reducing metastatic outgrowth in lungs by disrupting oncogenic mechanosignaling [12] [13] [14].

Non-Invasive Physical Plasma (NIPP): This novel approach disrupts cytoskeletal organization across ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer cell lines by inducing oxidative stress that damages actin and tubulin without triggering cytoprotective heat shock proteins [6] [15].

Antibody-Based Therapies: Monoclonal antibodies targeting cancer-specific plectin (CSP) on the cell surface show potential for selective drug delivery in ovarian cancer [10].

These approaches demonstrate the therapeutic potential of disrupting plectin-mediated cytoskeletal integration to combat invasive cancers, with plecstatin-1 showing particular promise in preclinical HCC models [12] [13].

Plectin serves as a critical integrator of cytoskeletal networks, with distinct expression patterns, organizational roles, and functional contributions that differentiate invasive from non-invasive cells. Through its mechanosensitive crosslinking capabilities, plectin regulates essential processes in cell invasion, including 3D migration, nuclear translocation, and oncogenic mechanosignaling. The comparative analysis presented herein provides researchers with methodological frameworks, quantitative benchmarks, and therapeutic insights for investigating cytoskeletal organization in the context of cell invasiveness. Emerging strategies that target plectin-mediated mechanisms offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in invasive cancers, particularly through the disruption of mechanical homeostasis that drives tumor progression and metastasis.

E-Cadherin Disruption and its Cascading Effects on Cytoskeletal Architecture

| Feature | Wild-Type (Non-Invasive) E-Cadherin Cells | Mutant (Invasive) E-Cadherin Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Microtubule Organization (OOP) [1] | Higher Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) | Significantly lower OOP |

| Microtubule Morphology [1] | Longer fibers | Shorter fibers |

| Microtubule Distribution [1] | More dispersed in the cytoplasm | More compactly distributed |

| Microtubule Radiality [1] | Variable radial patterns | Dispersed orientations, less radial |

| Primary Extrusion Direction [16] | Primarily apical extrusion | Preferential basal extrusion into the ECM |

| Cell-ECM Adhesion [16] | Normal adhesion strength | Increased adhesion to ECM |

| Invadopodia Formation [17] | Not typically observed | E-cadherin localizes to invadopodia, promoting structuration and ECM degradation |

Experimental Workflow for Cytoskeletal Analysis

A novel computational pipeline enables a detailed quantitative comparison of cytoskeletal architecture between non-invasive and invasive cells [1]. The methodology below allows researchers to systematically dissect the subtle cytoskeletal alterations triggered by E-cadherin disruption.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is designed to quantify fine alterations in the cytoskeleton of cells where E-cadherin function has been disrupted.

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture control cells (e.g., MDCK or MCF10A) and isogenic lines expressing mutant E-cadherin (e.g., p.L13_L15del). Grow cells on appropriate ECM-coated glass-bottom dishes to model cell-ECM interaction.

- Immunofluorescence Staining:

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes.

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Block with 1% BSA for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibody against α-tubulin (microtubule marker) overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution z-stack images using a confocal microscope with a 60x or higher magnification oil-immersion objective. Maintain identical laser power and gain settings across all samples.

- Image Processing and Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Apply deconvolution to remove noise and blur. Create a 2D maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the z-stacks.

- Filtering: Process images with a Gaussian filter to smooth the signal, followed by a Sato filter to highlight curvilinear structures of cytoskeletal fibers.

- Segmentation: Apply a Hessian filter to generate binary images. Skeletonize the binary images to create a 1-pixel-wide representation of each fiber.

- Feature Extraction: Use custom algorithms to automatically extract two classes of features:

- Line Segment Features (LSFs): Quantify fiber length, orientation (Orientational Order Parameter - OOP), and quantity (number of lines, Nl).

- Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNFs): Analyze compactness (Nl/Ac), radiality (radial score relative to nucleus centroid), and fiber-nucleus interconnection (average distance, Di).

This assay tests the ability of E-cadherin dysfunctional cells to detach from an epithelium and invade the underlying matrix, mimicking an early step in cancer dissemination.

- Generation of Co-culture Model:

- Label E-cadherin mutant cells (e.g., A634V, R749W, V832M) with a fluorescent cell tracker dye.

- Mix these labeled mutant cells at a highly diluted ratio (e.g., 1:100) with an excess of unlabeled wild-type cells.

- Seed the cell mixture on top of a thick collagen I matrix to form a confluent monolayer.

- Confocal Microscopy and Quantification:

- After 24-48 hours of culture, acquire xz-sections (side views) of the monolayer using confocal microscopy.

- Quantify the position of the nuclei of mutant (fluorescent) and wild-type cells relative to the apical-basal axis of the monolayer.

- A cell is scored as "basally extruded" if its nucleus is located below the basal plane of the wild-type monolayer.

E-Cadherin Disruption and Downstream Signaling

E-cadherin is not merely a passive adhesive molecule; its engagement or disruption initiates powerful signaling cascades that directly remodel the actin cytoskeleton, primarily through the Rho family of GTPases [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mutant E-cadherin Constructs | Model hereditary E-cadherin dysfunction to study loss of cell-cell adhesion. | p.L13_L15del, A634V, R749W, V832M mutants in HDGC research [1] [16]. |

| Laminin / Collagen I Matrix | Provides a physiological, supportive 3D environment for cell growth and invasion assays. | Substrate for cell culture in cytoskeleton analysis and basal extrusion assays [1] [16]. |

| Anti-α-Tubulin Antibody | Primary antibody for visualizing the microtubule network via immunofluorescence. | Key reagent for staining and segmenting cytoskeletal fibers [1]. |

| Pefabloc (Serine Protease Inhibitor) | Inhibits serine proteases like FAP/seprase to test their role in invasion. | Validates role of FAP in cancer cell invasion through urothelial barrier [19]. |

| Fluorescent Cell Tracker Dyes | Labels specific cell populations for tracking their behavior in co-culture. | Distinguishes E-cadherin mutant cells from wild-type neighbors in extrusion assays [16]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Engineered Cells | Creates isogenic cell lines with precise knockouts (e.g., CDH1+/-) to study E-cadherin loss. | Modeling E-cadherin downregulation in airway epithelial barrier dysfunction [20]. |

| Ykl-5-124 tfa | Ykl-5-124 tfa, MF:C30H34F3N7O5, MW:629.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SJ-172550 | SJ-172550, MF:C22H21ClN2O5, MW:428.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The quantitative data and experimental workflows presented provide a robust framework for objectively comparing cytoskeletal organization in invasive versus non-invasive cellular models. The integration of computational image analysis with mechanistic biochemical assays allows for a comprehensive dissection of how E-cadherin disruption serves as a master regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, driving pro-invasive cellular phenotypes.

{}

Cytoskeletal Drugs as Probes: Unraveling Function Through Targeted Disruption

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filamentous proteins, is a central regulator of cellular architecture, mechanics, and motility. Its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous diseases, particularly cancer, where it drives invasion and metastasis. This guide provides a comparative analysis of cytoskeleton-targeting drugs, evaluating their efficacy as biological probes and their potential as therapeutics. We objectively compare the performance of actin filament disruptors, Rho kinase inhibitors, and microtubule-targeting agents, supported by experimental data on their morphological, mechanical, and functional impacts on cells. Framed within the context of cytoskeletal organization in invasive versus non-invasive cells, this review integrates detailed experimental protocols, visualizes key signaling pathways, and catalogs essential research reagents to serve as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The cytoskeleton is a complex, integrated system composed of three primary filament types: actin filaments (AFs), microtubules (MTs), and intermediate filaments (IFs). This network is not a static scaffold but a dynamic structure that governs essential processes such as cell division, migration, and intracellular transport [21] [22]. In cancer, the cytoskeleton is hijacked to enable invasive behaviors; cells undergo dramatic rearrangements of their cytoskeletal architecture to breach tissues, enter the circulation, and form metastases [1] [22]. Consequently, drugs that selectively disrupt specific cytoskeletal components have become indispensable tools for dissecting the contribution of each filament system to cellular function and pathology.

These "cytoskeletal drugs" function through distinct mechanisms. Actin filament disruptors, such as Latrunculin A, directly target the polymerization dynamics of actin. In contrast, Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors act upstream, modulating the signaling pathways that control actomyosin contractility [23]. The specific disruption caused by these drugs allows researchers to infer the normal function of the cytoskeletal components they target. By comparing the effects of these agents on cellular morphology, mechanical properties, and migratory behavior—particularly in models of invasive and non-invasive cells—we can unravel the fundamental mechanisms driving diseases like cancer and identify potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Comparative Analysis of Major Cytoskeletal Drug Classes

This section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the primary classes of cytoskeleton-modulating agents, focusing on their mechanisms, cellular effects, and experimental outcomes.

Actin Filament Disruptors

Actin filament disruptors directly interfere with the polymerization or stability of actin, leading to a rapid dissolution of actin-based structures. The table below summarizes key drugs in this class and their observed experimental effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Actin Filament Disruptors

| Drug Name | Primary Mechanism of Action | Effect on Actin Structures | Quantified Effect on Cell Elasticity | Impact on Cell Migration/Invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latrunculin A | Sequesters G-actin monomers, preventing polymerization [23]. | Disassembles stress fibers and cortical actin [23]. | Distinct decrease in elastic modulus [24]. | Significantly inhibits migration and invasion [6]. |

| Cytochalasin D | Caps filament ends, preventing elongation [23]. | Disassembles stress fibers; can cause actin aggregation [24]. | Distinct decrease in elastic modulus [24]. | Inhibits migration by disrupting leading edge protrusions. |

| Jasplakinolide | Stabilizes actin filaments and promotes polymerization [24]. | Disaggregates filaments but does not disassemble stress fibers [24]. | No significant change in elastic modulus [24]. | Can inhibit migration by reducing filament turnover. |

Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors

ROCK inhibitors act by disrupting the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway, which is a major regulator of actomyosin contractility. By inhibiting myosin light chain phosphorylation, they indirectly cause actin cytoskeleton reorganization.

Table 2: Comparison of Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors

| Drug Name | Primary Mechanism of Action | Effect on Actin Structures & Contractility | Documented Effect on Tissue/Outflow | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y-27632 | Specific inhibitor of Rho kinase [23]. | Reduces MLC phosphorylation, leading to stress fiber disassembly and loss of focal adhesions [23]. | Relaxes contractions in TM strips; decreases outflow resistance in animal models [23]. | Induces cell rounding and intercellular separation; mimics effects of direct actin disruption. |

| H-1152 | Potent and selective ROCK inhibitor [23]. | Reduces basal MLC phosphorylation, changing cell shape and depolymerizing actin [23]. | Effectively decreases intraocular pressure in models [23]. | More potent than Y-27632 in some physiological assays. |

Microtubule-Targeting Agents

While the provided search results focus more on actin-targeted therapies, microtubules are a co-conspirator in cancer progression. The computational pipeline study revealed that microtubules in invasive cells with disrupted E-cadherin are shorter, have dispersed orientations, and are more compactly distributed [1]. This suggests that drugs stabilizing or destabilizing microtubules (e.g., Taxol, Vinca alkaloids) would profoundly alter the invasive architecture of cancer cells, though their use as probes is complicated by their essential role in mitosis.

Experimental Protocols for Probing Cytoskeletal Function

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for comparison, this section outlines standard methodologies for assessing the effects of cytoskeletal drugs.

Protocol: Quantifying Drug-Induced Changes in Cell Mechanics via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the mechanical role of the cytoskeleton [24].

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells (e.g., fibroblasts or cancer cells) onto sterile, glass-bottom culture dishes and allow them to adhere for 24-48 hours until they reach 60-70% confluence.

- Drug Treatment: Replace the medium with a serum-free medium containing the desired concentration of cytoskeletal drug (e.g., 1 µM Latrunculin A, 10 µM Cytochalasin D, or 10 µM Y-27632). Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO). Incubate for the determined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

- AFM Measurement:

- Use an AFM equipped with a colloidal probe (e.g., a silica bead with a 5-10 µm diameter) to ensure non-indenting measurements.

- Approach the cell surface at multiple locations (avoiding the nucleus) to obtain force-indentation curves.

- Maintain a consistent culture medium and temperature (37°C) during measurements.

- Data Analysis: Fit the force-indentation curves with an appropriate mechanical model (e.g., Hertz model) to extract the Young's modulus (Elastic Modulus). Compare the mean values from drug-treated cells to vehicle-treated controls using statistical tests (e.g., t-test). A significant decrease indicates a loss of mechanical stiffness, as seen with actin disruption [24].

Protocol: Assessing Cytoskeletal Architecture via Computational Image Analysis

This workflow, based on a novel computational pipeline, allows for the quantitative dissection of cytoskeletal organization from fluorescence images [1].

- Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Culture cells on appropriate substrates (e.g., laminin to mimic ECM interaction).

- Fix, permeabilize, and stain cells for a cytoskeletal target (e.g., α-tubulin for microtubules) and the nucleus.

- Acquire high-resolution Z-stack images using a fluorescence microscope.

- Image Pre-processing:

- Apply deconvolution to remove noise and blur.

- Create a 2D maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the Z-stacks.

- Process images with a Gaussian filter to smooth signal and a Sato filter to highlight curvilinear structures.

- Feature Extraction:

- Generate binary images using a Hessian filter and skeletonize the structures.

- Use the pipeline to automatically extract two classes of features:

- Line Segment Features (LSFs): Quantify fiber orientation, length, and compactness.

- Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNFs): Describe connectivity, radiality, and complexity via graph networks.

- Data Interpretation:

- Calculate the Orientational Order Parameter (OOP). A lower OOP indicates disorganized fibers, a signature of invasive cells [1].

- Compare metrics like fiber compactness and radiality between experimental groups (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant E-cadherin cells) to statistically evaluate cytoskeletal reorganization.

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core mechanisms and methodologies discussed in this guide.

Rho/ROCK Signaling Pathway in Cytoskeletal Regulation

Diagram 1: Key pathways regulating actin and myosin. This diagram illustrates the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway that regulates actomyosin contractility and stress fiber formation. It highlights the points of inhibition for ROCK inhibitors (like Y-27632) and the direct target of actin filament disruptors (like Latrunculin A).

Computational Image Analysis Pipeline

Diagram 2: Workflow for cytoskeleton architecture analysis. This flowchart outlines the computational pipeline for quantitatively analyzing cytoskeletal architecture from fluorescence images, culminating in the extraction of Line Segment and Cytoskeleton Network Features [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents, drugs, and tools for conducting research in cytoskeletal dynamics and targeted disruption.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Disruption Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Key Characteristics / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Latrunculin A & B | Selective actin monomer sequestering agent; disrupts actin dynamics [23] [25]. | Ideal for probing the specific role of actin polymerization in processes like migration and mechanotransduction. |

| Cytochalasin D | Actin filament capping agent; prevents filament elongation [23] [24]. | Useful for rapid disruption of existing actin networks. Can cause actin aggregation. |

| Y-27632 | Cell-permeable, potent ROCK inhibitor [23]. | A standard tool for investigating Rho/ROCK-mediated contractility and its role in cell morphology and tissue function. |

| Jasplakinolide | Actin-stabilizing agent; promotes polymerization [24]. | Used to study the effects of reduced actin turnover. Notably, it does not soften cells in AFM studies [24]. |

| Anti-β-Actin Antibody | Immunofluorescence staining; functional inhibition [25]. | Beyond imaging, specific antibodies can be microinjected to inhibit actin function and disrupt drug resistance [25]. |

| PSC833 & Probenecid | Inhibitors of drug transporters P-glycoprotein and MRP1 [25]. | Used to study the link between cytoskeleton-associated drug resistance and chemotherapeutic efficacy. |

| Laminin-coated Substrata | ECM substrate for cell culture. | Provides a supportive environment for studying cell-ECM interactions and their effect on cytoskeletal organization [1]. |

| LYP-IN-1 | LYP-IN-1|p32 Inhibitor|For Research Use | LYP-IN-1 is a potent and selective inhibitor of the p32 protein. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

| JAK-IN-5 hydrochloride | JAK-IN-5 hydrochloride, MF:C27H32ClFN6O, MW:511.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The targeted disruption of the cytoskeleton with specific pharmacological probes remains a powerful strategy for elucidating its complex functions in health and disease. As this guide has detailed, actin disruptors and ROCK inhibitors are highly effective at breaking down the mechanical integrity and contractile machinery of cells, providing direct evidence for the cytoskeleton's role in processes from glaucoma to cancer metastasis. The experimental data clearly shows that while both classes induce similar phenotypic outcomes like stress fiber loss, their mechanisms—direct molecular intervention versus indirect signaling modulation—are distinct and must be chosen based on the specific research question.

Future research will be shaped by several key frontiers. First, the development of more cell-type-specific agents and prodrugs is crucial to minimize off-target effects and enhance therapeutic potential, as initially explored in glaucoma research [23]. Second, the integration of advanced computational pipelines, like the one described here, will move the field beyond qualitative description to robust, quantitative analysis of cytoskeletal architecture, enabling the discovery of novel, disease-specific signatures [1]. Finally, the emergence of nanomaterials as cytoskeleton-modulating platforms offers exciting possibilities for spatiotemporally controlled drug delivery, potentially overcoming the limitations of conventional small molecules [21]. By combining precise pharmacological probes with quantitative readouts and advanced delivery systems, researchers can continue to unravel the intricate functions of the cytoskeleton and translate these insights into next-generation therapeutics.

From Images to Insights: Cutting-Edge Computational and Real-Time Analysis Tools

The quantitative analysis of cytoskeletal architecture provides critical insights into cellular behavior, particularly in cancer research where specific cytoskeletal patterns are associated with invasive potential [1]. Computational pipelines for automated feature extraction are indispensable for objectively identifying these subtle, yet biologically significant, morphological changes. These tools enable researchers to move beyond qualitative descriptions and extract high-dimensional data on features like line segments and network topology from complex biological images.

This guide compares automated feature extraction pipelines, focusing on their application in quantifying cytoskeletal organization differences between invasive and non-invasive cells. We evaluate computational tools based on their feature extraction capabilities, performance metrics, and applicability to cytoskeletal analysis, providing researchers with objective data to select appropriate methodologies for their specific research contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Extraction Tools

Different computational approaches have been developed for feature extraction from biological images, each with unique strengths in handling specific data types and analytical tasks.

Table 1: Computational Pipelines for Feature Extraction

| Pipeline Name | Primary Function | Segmentation Approach | Tracking Capability | Dimensionality | Key Cytoskeletal Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nellie [26] | Organelle segmentation & tracking | Multiscale Frangi filter, hierarchical deconstruction | Radius-adaptive pattern matching, subvoxel tracking | 2D, 3D, live-cell | Morphology, motility, sub-organellar regions, graph networks |

| Cytoskeletal Pipeline [1] | Cytoskeletal architecture analysis | Gaussian, Sato, & Hessian filtering, skeletonization | Not specified | 2D (from 3D Z-stacks) | Line orientation (OOP), compactness, radiality, fiber length, bundling |

| Geometric Feature Method [27] | 3D line segment extraction | Region growing, geometric feature enhancement, CNN | Not specified | 3D large-scale | Line segment completeness, correctness, hierarchical topology |

Performance and Experimental Data

Performance benchmarking reveals how effectively these pipelines extract meaningful biological data. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from experimental validations.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics

| Pipeline / Study | Experimental Context | Key Quantitative Findings | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Analysis Pipeline [1] | E-cadherin mutant (invasive) vs. wild-type (non-invasive) cells | Invasive cells: ↓OOP (dispersed orientations), ↓Fiber Length, ↑Compactness [1] | Successfully distinguished invasive vs. non-invasive cytoskeletal architectures |

| Geometric Line Extraction [27] | Large-scale outdoor point clouds (Semantic3D, WHU-TLS) | Completeness: ~86%, Correctness: ~86%, Speed: 25,000 points/sec [27] | High accuracy and efficiency in complex environments |

| Nellie [26] | Diverse organelle segmentation & tracking tasks | Outperformed state-of-the-art tools in segmentation across simulated datasets [26] | Superior to custom-trained Swin UNETR models in generalization [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cytoskeletal Feature Extraction from Immunofluorescence Images

This protocol is designed for quantifying microtubule reorganization in 2D cell cultures, suitable for comparing invasive and non-invasive cancer cell lines [1].

Sample Preparation

- Cell Culture: Plate cells on laminin-coated coverslips to model cell-ECM interactions.

- Staining: Immunofluorescence staining for α-tubulin (microtubules) and a nuclear marker (e.g., DAPI).

- Imaging: Acquire high-resolution Z-stack images using a fluorescence microscope.

Image Preprocessing

- Deconvolution: Remove noise and blur, improving contrast and resolution.

- Z-Stack Projection: Create a 2D maximum intensity projection (MIP) from the deconvoluted Z-stacks.

- Filtering Pipeline:

- Apply a Gaussian filter to smooth the fluorescence signal.

- Apply a Sato filter to highlight curvilinear structures of cytoskeletal fibers.

- Apply a Hessian filter to generate a binary image for segmentation.

Segmentation and Skeletonization

- Process the binary image to create a skeleton representation of the cytoskeletal network.

Feature Extraction

- Line Segment Features (LSFs): Extract features like length and orientation from the skeleton.

- Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNFs): Calculate graph-based features from network nodes.

- Key Metrics:

- Orientational Order Parameter (OOP): Measures fiber alignment. Lower angular distribution yields higher OOP.

- Fiber Compactness: Number of fibers per unit area (Nl/Ac).

- Radiality Score (RS): Measures how fibers radiate from the nucleus centroid.

The workflow for this analysis is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Nellie for 3D Organelle Segmentation and Tracking

This protocol is used for 3D analysis of organelle morphology and dynamics, which can be applied to study cytoskeletal components in volumetric data [26].

Input Data Preparation

- Acquire 2D/3D or 4D (3D + time) live-cell microscopy images.

- Ensure proper image metadata (voxel dimensions, time interval) is available.

Metadata Validation and Preprocessing

- Metadata Module: Nellie automatically detects dimension order and resolutions, allowing for user correction.

- Multiscale Filtering: A modified Frangi filter enhances structural contrast based on local architecture, not just intensity, adapting to various magnifications.

Hierarchical Segmentation

- Semantic Segmentation: Minotri thresholding creates an initial organellar landscape mask.

- Instance Segmentation: Connected-components labeling identifies spatially disconnected organelles.

- Subcompartments: Skeletonization and junction node detection deconstruct networks into individual branches.

Motion Tracking and Feature Extraction

- Motion-Capture Markers: Generate tracking points independently of segmentation labels for consistency across frames.

- Pattern Matching: Use radius-adaptive, variable-range feature matching to create linkages between time points.

- Feature Output: Extract a hierarchical pool of spatial and temporal features for analysis.

The workflow for this protocol is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cytoskeletal Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevance to Feature Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| α-Tubulin Antibody [1] | Immunofluorescence staining of microtubules | Primary target for visualizing microtubule networks in the cytoskeletal pipeline. |

| AF488-phalloidin / SiR-jasplakinolide [28] | F-actin staining for fixed / living cells | Labels actin filaments for organization analysis; used in polarimetry. |

| Genetically Encoded Actin Reporters [28] | Live-cell imaging of actin organization (e.g., constrained GFP fusions) | Enables measurement of filament orientation (Ï) and alignment (ψ) via polarimetry in living samples. |

| Laminin-Coated Substrata [1] | Provides physiologically relevant ECM for cell culture | Models cell-ECM interactions crucial for studying invasive phenotypes. |

| Nellie Software [26] | Automated segmentation and tracking pipeline | Provides objective, high-throughput analysis of organelle/cytoskeletal morphology and dynamics. |

| Napari Viewer [26] | User-friendly GUI for image analysis | Facilitates visualization of intermediate images and tracks from Nellie without coding. |

| JH-XI-10-02 | JH-XI-10-02, MF:C53H69N5O9, MW:920.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA hydrochloride | H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA hydrochloride, MF:C27H37ClN8O5, MW:589.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data indicates that tool selection should be driven by specific research questions. For dedicated 2D cytoskeletal architecture analysis, the specialized pipeline [1] offers targeted metrics like OOP and radiality that directly discriminate invasive phenotypes. For comprehensive 3D and dynamic studies, Nellie's [26] generalizable, hierarchical approach provides unparalleled depth in quantifying morphology and motility.

The consistent finding that invasive cells display shorter microtubules with disorganized orientations and compact distribution [1] provides a quantifiable signature of metastatic potential. Integrating these computational pipelines with advanced imaging techniques, such as polarimetry [28], will further deepen our understanding of cytoskeletal dynamics. These automated, unbiased extraction tools are paving the way for new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in cancer research.

The architectural organization of cellular and subcellular components is a critical determinant of biological function, particularly in the context of disease progression such as cancer invasion and metastasis. Quantitative parameters that can objectively measure organizational properties provide powerful tools for distinguishing between physiological states that may appear similar through qualitative assessment alone. This guide focuses on three key quantitative parameters—orientational order, fractal dimension, and connectivity—that have emerged as essential metrics for characterizing biological organization, particularly in cytoskeletal architecture and cellular patterning. These parameters enable researchers to move beyond subjective descriptions to objective, computationally-derived measurements that can detect subtle yet biologically significant changes in cellular organization associated with transformative processes like the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells.

The comparative analysis presented here examines the underlying principles, methodological approaches, and experimental applications of these parameters specifically within the context of distinguishing invasive from non-invasive cellular phenotypes. By providing a structured comparison of these quantitative tools, along with detailed experimental protocols and visualization approaches, this guide aims to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select and implement the most appropriate parameters for their specific research questions in cytoskeletal organization and cancer cell behavior.

Comparative Analysis of Quantitative Parameters

Table 1: Core Quantitative Parameters for Cellular Organization Analysis

| Parameter | Mathematical Basis | Measurement Range | Biological Interpretation | Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) | Liquid crystal physics; tensor analysis of vector orientation [29] [30] | 0 (isotropic) to 1 (perfectly aligned) | Degree of alignment and directional consistency of cytoskeletal elements | Invasive cells show significantly lower OOP, indicating disorganized fibers [1] |

| Co-Orientational Order Parameter (COOP) | Extension of OOP framework to correlation between two constructs [29] [30] | 0 (uncorrelated) to 1 (perfectly correlated) | Correlation in orientation between different cytoskeletal components (e.g., actin & Z-lines) | Not specifically reported for invasion, but quantifies coordination between structural elements |

| Fractal Dimension (FD) | Modified Blanket Method analyzing power law relationship between surface area and resolution [31] | 2.0-4.5 for biological structures | Structural complexity and space-filling characteristics | Higher FD associates with increased aggressiveness in prostate cancer nuclei [32] |

| Local Connected Fractal Dimension (LCFD) | Local implementation of FD measuring connectivity [32] | Varies by biological context | Regional complexity and interconnection density | LCFD >1.7051 associates with high-aggressiveness prostate carcinomas [32] |

Table 2: Complementary Metrics for Comprehensive Organizational Profiling

| Metric Category | Specific Parameters | Application Context | Invasion-Associated Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Distribution | Lacunarity (λ) [32] | Measures heterogeneity and "gappiness" of spatial patterns | λ < 0.7 in high-aggression prostate cancers [32] |

| Information Theory | Shannon Entropy (H) [32] | Quantifies disorder and uncertainty in spatial organization | H > 0.9 in high-complexity, aggressive carcinomas [32] |

| Morphometric | Line Segment Features (LSF) and Cytoskeleton Network Features (CNF) [1] | Quantifies fiber length, bundling, and network architecture | Invasive cells show shorter microtubules with dispersed orientations [1] |

| Radiality | Radial Score (RS) [1] | Measures pattern organization relative to a central point (e.g., nucleus) | Variable based on cell type and context [1] |

Parameter-Specific Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) and COOP

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation: The Orientational Order Parameter (OOP) is derived from liquid crystal physics and provides a quantitative measure of the degree of alignment within a system of pseudo-vectors representing biological structures such as cytoskeletal fibers [29] [30]. The parameter is calculated through tensor analysis of vector orientation data. For a set of pseudo-vectors K, the order tensor is defined as:

ð•‹K = 2⟨ki,xki,x⟩⟨ki,xki,y⟩⟨ki,xki,y⟩⟨ki,yki,y⟩ - ð•€

where ð•€ is the identity matrix, and the OOP is the maximum eigenvalue of this tensor [30]. The Co-Orientational Order Parameter (COOP) extends this framework to measure correlation between two different constructs (P and Q) by creating a new field F representing the angle between corresponding vectors:

COOPPQ = ⟨fi,x²⟩ + ⟨fi,y²⟩ - 1 + √(⟨fi,x²⟩ - ⟨fi,y²⟩)² + 4⟨fi,xfi,y⟩²

where fi,x = pi·qi and fi,y = |pi×qi| [30]. This enables quantification of how well the orientation of one biological construct (e.g., actin filaments) correlates with another (e.g., Z-lines).

Experimental Workflow for Cytoskeletal Analysis:

- Sample Preparation and Imaging: Culture cells on appropriate substrates, fix at relevant time points, and perform immunofluorescence staining for cytoskeletal components (e.g., α-tubulin for microtubules). Acquire high-resolution Z-stack images using confocal microscopy [1].

- Image Preprocessing: Apply deconvolution to remove noise and blur, followed by maximum intensity projection (MIP) to create 2D images. Process images with Gaussian filtering to smooth fluorescence signal, Sato filtering to highlight curvilinear structures, and Hessian filtering to generate binary images [1].

- Fiber Skeletonization: Convert binary images to skeletonized representations using thinning algorithms to reduce fibers to single-pixel width representations while preserving topology [1].

- Orientation Extraction: Calculate local orientation vectors using line segment detection or gradient-based methods. For each detected fiber segment, compute the orientation angle relative to a reference axis.

- OOP/COOP Computation: Implement the tensor-based calculations described above using computational platforms such as MATLAB or Python. The COOP is particularly valuable for assessing coordination between different cytoskeletal elements in engineered cardiac tissues, where perfect correlation between actin filaments and Z-lines is expected [29].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for Orientational Order Parameter analysis

Fractal Dimension and Connectivity Metrics

Theoretical Foundation of Fractal Analysis: Fractal dimension quantifies the structural complexity and space-filling characteristics of biological structures by measuring how detail changes with scale. The Modified Blanket Method (MBM) operates by interpreting images as topographical maps and calculating the local surface area as a function of image resolution [31]. The power law relationship between surface area (SA) and pixel size defines the fractal dimension:

FD = 2 - Δlog(SA)/Δlog(pixel size)

This approach enables computation of local FD values at each pixel, facilitating the analysis of specific structures or individual cells [31]. For connectivity assessment, the Local Connected Fractal Dimension (LCFD) provides a specialized metric for evaluating interconnection density within cellular structures.

Experimental Protocol for Fractal Analysis:

- Image Acquisition: Obtain high-quality images of biological structures of interest (e.g., mitochondrial networks, cancer cell nuclei, or cytoskeletal patterns) using appropriate microscopy techniques. For mitochondrial analysis, NADH autofluorescence images can be utilized [31].

- Region of Interest Definition: Delineate precise regions of interest (ROIs) for analysis. For intracellular structures, accurate cell segmentation is crucial, potentially employing clone stamping to fill backgrounds with intracellular feature copies [31].

- MBM Implementation:

- Resample both the image and convolution kernel proportionally

- Compute horizontal and vertical gradients using X- and Y-gradient kernels ([1,-1,0] and [0,-1,1]áµ€ respectively)

- Sum absolute gradient values by convolving with a binary disk kernel

- Calculate local surface area maps by adding horizontal and vertical gradients

- Resample SA maps back to original dimensions

- Repeat with progressively reduced kernel sizes (decrementing by 1 pixel until 1×1 kernel remains)

- Determine FD from the power law exponent relating local SA measurements to pixel sizes [31]

- Validation and Calibration: Assess algorithm accuracy using simulated cell images with known fractal dimension. Validate against established methods like Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis, which computes a radial average of the 2D Fourier transform of the image [31].

Application to Cancer Cell Nuclei: In prostate cancer diagnostics, fractal analysis of cancer cell nuclei spatial distribution has demonstrated significant diagnostic value. Specific cut-off values for global fractal capacity dimension (D0) enable stratification of carcinomas into distinct aggressiveness classes [32]:

- D0 < 1.5820: Low complexity, low aggressive carcinomas

- D0 > 1.6980: High complexity, high aggressive carcinomas

Complementary parameters including LCFD, lacunarity (λ), and Shannon entropy (H) further refine this classification, with high-aggression carcinomas typically showing LFD > 1.7644, LCFD > 1.7051, H > 0.9, and λ < 0.7 [32].

Figure 2: Fractal dimension analysis workflow using the Modified Blanket Method

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Organizational Analysis

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Reagents | α-tubulin antibodies [1] | Microtubule visualization | Enables cytoskeletal architecture analysis |

| Phalloidin conjugates | Actin filament staining | Highlights actin cytoskeleton organization | |

| Hoechst 33342 [33] | Nuclear staining | Defines nuclear boundaries for spatial reference | |

| Computational Tools | MATLAB with customized algorithms [31] [1] | Implementation of MBM, OOP/COOP calculations | Flexible programming environment for custom analysis |

| CellProfiler [33] | Image analysis and segmentation | Open-source platform for high-throughput screening | |

| Topcat [33] | Data visualization and plotting | Specialized tools for biological data representation | |

| Reference Materials | Simulated cell images with known FD [31] | Algorithm validation | Provides ground truth for methodological verification |

| Population-based input functions [34] | Calibration and normalization | Enables cross-study comparisons |

Integration of Multiple Parameters for Enhanced Classification

The most powerful applications of these quantitative parameters emerge when they are integrated to create multidimensional organizational profiles. Research demonstrates that combining fractal dimension with complementary metrics like lacunarity and entropy significantly enhances the discrimination between aggressive and non-aggressive cancer phenotypes [32]. Similarly, the concurrent analysis of orientational order with morphometric parameters (e.g., fiber length, compactness, and radiality) provides a more comprehensive understanding of cytoskeletal reorganization in invasive cells [1].

This integrated approach is particularly valuable in the context of cytoskeletal organization in invasive versus non-invasive cells. Studies have revealed that cancer cells with disrupted E-cadherin and increased invasive potential display distinctive cytoskeletal architecture characterized by shorter microtubules, dispersed orientations (lower OOP), and more compact distribution compared to their non-invasive counterparts [1]. These organizational differences, quantifiable through the parameters described in this guide, provide objective markers of invasive potential that could complement traditional histopathological analysis.

The implementation of these quantitative parameters continues to evolve with advancements in computational power and imaging technology. Future directions include the development of standardized reference datasets, improved algorithms for three-dimensional organizational analysis, and integration with machine learning approaches for automated classification of cellular phenotypes based on organizational signatures.

In vitro cell culture models represent a foundational technology in cancer research, particularly for preclinical drug development. However, traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures grown on rigid plastic substrates fail to replicate the complex and dynamic nature of the tumor microenvironment (TME). This microenvironment is a sophisticated ecosystem comprising cancer cells, stromal cells, immune components, endothelial cells, signaling molecules, and the extracellular matrix (ECM). The limitations of 2D models contribute to a significant translational gap, with approximately only 10% of anticancer drug candidates that show promise in conventional cultures progressing successfully to clinical trials [35].

The transition to three-dimensional (3D) culture models addresses these deficiencies by providing a platform that more accurately mimics the structural, biochemical, and cellular interactions found in vivo. These advanced models, including multicellular spheroids, organoids, and bioprinted constructs, recapitulate critical tumor characteristics such as oxygen and nutrient gradients, cell-ECM interactions, and the development of drug-resistant phenotypes [36] [37] [35]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading 3D culture technologies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform their application in cancer research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of 3D Culture Technologies

Various 3D culture technologies have been developed, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and suitability for specific research applications. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary scaffold-free and scaffold-based methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary 3D Cell Culture Technologies

| Technology | Classification | Key Features | Throughput | Physiological Relevance | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Drop [35] | Scaffold-free | Cells aggregate at liquid-air interface to form spheroids | Medium | Medium - Recapitulates cell-cell contacts; lacks ECM | Produces uniform, tightly-packed spheroids; no artificial scaffold | Difficult medium changes; limited spheroid size; absent cell-ECM interactions |

| Forced Floating [35] | Scaffold-free | Cells form spheroids on ultra-low attachment surfaces | High | Medium - Recapitulates cell-cell contacts; lacks ECM | Simple protocol; compatible with various assays; uniform spheroid size | Absent cell-ECM interactions; does not fully mimic tumor physiology |

| Bioreactors [35] | Scaffold-free | Spheroid formation via agitated suspension culture | High (for large quantities) | Medium - Recapitulates cell-cell contacts; lacks ECM | Generates large spheroid quantities; long-term viability | Significant spheroid size variation; potential shear stress damage |

| Organoids [36] [38] | Scaffold-based | Stem cells differentiate into 3D, organ-like structures in a matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | Low to Medium | High - Retains tumor heterogeneity; contains multiple cell types | Preserves patient-specific genetics and tumor heterogeneity; high clinical predictive value | Technically challenging; culture instability; batch-to-batch matrix variability |

| 3D Bioprinting [39] | Scaffold-based | Layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks (cells + biomaterials) to create complex structures | Medium (Rapidly improving) | High - Customizable architecture; can incorporate vasculature and multiple cell types | High precision and control over TME composition and spatial organization; rising integration with AI for optimization | High cost; requires specialized equipment; complex protocol optimization (bioink, parameters) |

| Tumor-on-Chip [37] | Scaffold-based or free | Microfluidic devices culture cells in 3D gels or as spheroids under perfused flow | Low to Medium | High - Mimics fluid flow, shear stresses, and systemic delivery | Enables real-time monitoring of metabolites (e.g., glucose, lactate); models delivery dynamics | Specialized device design and operation; lower throughput |

Quantitative Data from 2D vs. 3D Model Comparisons

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate significant phenotypic and functional differences between cells cultured in 2D versus 3D formats. The following tables summarize key experimental findings that highlight the superior biological relevance of 3D models.

Table 2: Phenotypic and Behavioral Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Morphology [40] | Flat, stretched | In vivo-like, often spherical | 3D morphology influences cytoskeletal organization, cell polarity, and mechanotransduction. |

| Proliferation Rate [36] [37] | Rapid, contact-inhibited | Slower, more in vivo-like | Models tumor dormancy and quiescent cell populations often resistant to therapy. |