Advanced Strategies for Cytoskeletal Drug Target Compound Screening: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern compound screening strategies targeting the cytoskeleton for drug discovery.

Advanced Strategies for Cytoskeletal Drug Target Compound Screening: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern compound screening strategies targeting the cytoskeleton for drug discovery. It covers the foundational biology of microtubules, actin, and other cytoskeletal components as validated therapeutic targets, explores established and emerging high-throughput screening methodologies including tubulin polymerization assays and phenotypic profiling, addresses key challenges in specificity and predictive value, and examines advanced validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current knowledge to guide the development of next-generation cytoskeletal-targeted therapeutics with improved efficacy and reduced side effects for cancer and other diseases.

The Cytoskeleton as a Therapeutic Target: Unveiling Molecular Complexity and Druggable Sites

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary cytoskeletal targets in drug discovery, and what associated diseases are being investigated? The cytoskeleton offers several high-value targets for therapeutic intervention, primarily focused on microtubules and actin, with relevance to cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and bacterial infections. The table below summarizes key targets and their therapeutic context.

Table 1: Key Cytoskeletal Targets in Drug Discovery

| Target Protein | Associated Diseases | Common Assay Types |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin | Cancer, Gout, Arthritis | Polymerization, Binding, Spin-down, Live cell [1] |

| Kinesin (e.g., KIF18A) | Cancer, Neurodegeneration | Microtubule-activated ATPase [1] |

| Cardiac Myosin | Cardiomyopathies | Actin-activated ATPase, Calcium-activated ATPase [1] |

| FtsZ (Bacterial) | Bacterial Infection | Polymerization, GTPase [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Off-Target Effects in Cytoskeletal Drug Screens

- Problem: A compound designed to inhibit a specific kinesin (e.g., KIF18A) shows unexpected cellular effects, suggesting off-target activity.

- Background: Many cytoskeletal proteins, such as kinesins, belong to large families with homologous structures, increasing the risk of cross-reactivity [1].

- Solution: Implement a comprehensive motor panel counter-screen.

- Protocol: Test your lead compounds against a panel of related motor proteins (e.g., KIF2, KIF3C, KIF11, KIF20A, etc.) to determine IC₅₀ values for each [1].

- Expected Outcome: Confirmation of target specificity. For example, a high-quality inhibitor will be highly specific to KIF18A and its close homologs (KIF18B, KIF19A) while showing minimal activity against other kinesins [1].

- Data Interpretation: Prioritize compounds with a high selectivity index for further development.

FAQ 2: How does the cytoskeleton contribute to drug resistance, particularly to chemotherapeutics like paclitaxel? A novel mechanism of resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs like paclitaxel involves the interplay between tubulin post-translational modifications and the cytoskeletal component septins [2].

- Key Players:

- Tubulin Polyglutamylation: Catalyzed by enzymes TTLL5 (branching initiation) and TTLL11 (chain elongation), this modification alters the microtubule surface [2].

- Septin Overexpression: Specifically, the overexpression of septins (SEPT2, SEPT6, SEPT7, SEPT9_i1) and their relocalization from actin fibers to microtubules is a critical event [2].

- Resistance Mechanism: High levels of tubulin polyglutamylation and SEPT9_i1 create a scaffold on microtubules that enhances the recruitment of proteins like CLIP-170 and MCAK. These proteins increase microtubule dynamics, thereby counteracting the stabilizing effect of paclitaxel and leading to drug resistance [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating Paclitaxel Resistance in a Cell Model

- Problem: Your previously paclitaxel-sensitive cancer cell line has developed resistance.

- Hypothesis: Resistance is driven by the septin-polyglutamylation pathway.

- Experimental Approach:

- Expected Result: Cells overexpressing the combination of septins and polyglutamylases will show significantly higher survival rates in paclitaxel compared to control cells, confirming the sufficiency of this mechanism to induce resistance [2].

FAQ 3: What is the function of septins in cytoskeletal crosstalk? Septins are considered the fourth component of the cytoskeleton and are crucial for mediating crosstalk between microtubules and actin filaments [3] [4]. They act as a molecular linker that captures and guides the growth of actin filaments along microtubule lattices [3]. This function is essential for cellular morphogenesis, particularly in structures like neuronal growth cones, where it helps maintain the peripheral actin network that fans out from microtubules [3].

Comparative Data Tables

Table 2: Core Structural and Functional Properties of Cytoskeletal Components

| Property | Microfilaments (Actin) | Intermediate Filaments | Microtubules | Septins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~7 nm [5] | ~10 nm [5] [6] | ~23 nm [5] [6] | Filamentous GTP-binding proteins [4] |

| Protein Subunit | Actin [5] | Tissue-specific (e.g., Keratin, Vimentin, Neurofilaments, Lamins) [5] [6] | α- and β-Tubulin heterodimer [5] | Hetero-oligomers (e.g., SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7) [4] [2] |

| Dynamic Instability | Yes [6] | No [6] | Yes [6] | More stable than actin/MTs; assembly state affects function [4] |

| Primary Functions | Muscle contraction, cell movement, cytokinesis, maintenance of cell shape [5] | Mechanical strength, organelle anchoring, nuclear integrity [5] [6] | Intracellular transport, chromosome segregation, cell motility (cilia/flagella) [5] | Scaffold & diffusion barrier; direct actin-microtubule cross-linking [3] [4] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay for Compound Screening

This assay is a cornerstone for identifying compounds that stabilize or destabilize microtubules, a key mechanism for anti-cancer drugs [1].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a solution of purified porcine brain tubulin in a chilled GTP-supplemented polymerization buffer [1].

- Compound Addition: Add the test compound to the tubulin solution on ice. Include controls (e.g., vehicle control, paclitaxel as a stabilizer, vinca alkaloid as a destabilizer).

- Initiate Polymerization: Transfer the solution to a pre-warmed cuvette and immediately place it in a spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature-controlled chamber set to 37°C.

- Data Collection: Monitor the increase in turbidity (optical density) at 340 nm over time. Microtubule polymerization leads to a increase in light scattering, which appears as a sigmoidal curve: a lag phase (nucleation), a growth phase (elongation), and a plateau phase (steady state) [1].

- Data Analysis: Compare the polymerization kinetics of the test sample to controls. Compounds that stabilize microtubules will typically show a shorter lag phase and a steeper growth phase, while destabilizers will suppress the overall increase in OD₃₄₀.

Protocol 2: Reconstitution of Septin-Mediated Actin-Microtubule Crosstalk

This assay visually demonstrates how septins directly couple actin filaments to microtubules [3].

- Component Preparation:

- Purify and stabilize microtubules.

- Purify actin and pre-polymerize into filaments (F-actin) using phalloidin for stabilization.

- Purify recombinant septin complexes (e.g., SEPT2/6/7) [3].

- Assay Assembly for TIRF Microscopy:

- Immobilize stabilized microtubules on a passivated glass chamber.

- Coat the microtubules with a physiological concentration (e.g., 200-500 nM) of the septin complex.

- Introduce pre-polymerized, fluorescently labeled actin filaments into the chamber.

- Image Acquisition: Use time-lapse Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to capture binding events.

- Analysis: Quantify the percentage of microtubule length decorated with actin filaments in the presence vs. absence of septins. In the presence of septins, you will observe stable capture and alignment of actin filaments along the microtubule lattice, and even polymerization of actin from the microtubule-bound sites [3].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Resistance pathway.

Diagram 2: Septin crosstalk mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Compound Screening Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Tubulin | Core subunit for in vitro polymerization and binding assays. | Screening for compounds that modulate microtubule stability [1]. |

| Recombinant Septin Complexes | For reconstituting cytoskeletal crosstalk and studying septin-specific functions. | In vitro assays to test if a compound disrupts septin-mediated actin-microtubule binding [3]. |

| Stabilized Actin Filaments (F-actin) | Pre-formed actin polymers for interaction and motor protein assays. | Studying myosin function or actin-septin interactions [1] [3]. |

| Kinesin Motor Panel | A set of purified kinesin proteins for selectivity screening. | Counter-screening to ensure a kinesin inhibitor is target-specific and avoids off-target effects [1]. |

| Polyglutamylation Enzymes (TTLL5, TTLL11) | To introduce specific tubulin post-translational modifications in vitro. | Modeling the modified microtubule surface found in paclitaxel-resistant cells [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Microtubule-Targeting Agent Research

FAQ 1: What are the primary binding sites on tubulin for clinically approved MTAs, and how do they affect microtubule dynamics?

Microtubule-Targeting Agents (MTAs) exert their effects by binding to specific sites on tubulin, primarily on the β-tubulin subunit, leading to either stabilization or destabilization of microtubules [7] [8]. The table below summarizes the key binding sites and their mechanisms.

- Table 1: Key Tubulin Binding Sites and Mechanisms of Action

| Binding Site | Agent Class | Effect on Microtubules | Mechanism of Action | Representative Approved Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinca Domain | Vinca Alkaloids | Destabilization | Inhibits tubulin assembly by sequestering tubulin into aggregates; creates a wedge between tubulin dimers [7] [9]. | Vinblastine, Vincristine [9] |

| Taxane Site | Taxanes | Stabilization | Binds to β-tubulin in the microtubule lumen, promoting polymerization and stabilizing the lattice [7] [9]. | Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Cabazitaxel [9] |

| Colchicine Site | Colchicine, Combretastatins | Destabilization | Prevents the conformational change in tubulin required for polymerization [7]. | Colchicine (non-cancer use) [7] |

| Maytansine Domain | Maytansinoids | Destabilization | Inhibits the addition of tubulin dimers to microtubule plus ends [7] [8]. | mertansine (DM1) used in ADC Kadcyla [10] [7] |

Troubleshooting Tip: If your MTA is not producing the expected cellular phenotype (e.g., mitotic arrest), verify its binding site and intended mechanism. Off-target effects or resistance mechanisms, such as point mutations in the binding site or overexpression of specific tubulin isotypes, can alter drug efficacy [11] [7].

Diagram 1: Cellular outcomes of MTA mechanisms.

FAQ 2: Which MTAs have been successfully developed into Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs), and what are their components?

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) represent a major advancement in targeted cancer therapy, linking the cytotoxicity of MTAs to the specificity of monoclonal antibodies [10]. This design allows for precise delivery of the payload to cancer cells, minimizing off-target effects.

- Table 2: Clinically Approved Microtubule-Targeting ADCs

| Drug (Trade Name) | Target | Antibody | Linker | Cytotoxic Payload (MTA Class) | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) | HER2 | Trastuzumab (IgG1) | Non-cleavable | DM1 (Maytansinoid) [7] | HER2+ Breast Cancer [10] |

| Enfortumab vedotin (Padcev) | Nectin-4 | IgG1 | Cleavable | MMAE (Vinca-site binder) [10] | Urothelial Carcinoma [10] |

| Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) | CD30 | Chimeric mAb (cAC10) | Cleavable | MMAE (Vinca-site binder) [10] | Hodgkin Lymphoma, sALCL [10] |

| Belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) | BCMA | IgG1 | Non-cleavable | MMAF (Auristatin) [10] [12] | Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma [13] [12] |

| Sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) | TROP-2 | IgG1 | Cleavable | SN-38 (Topoisomerase I inhibitor) | TNBC, Urothelial Carcinoma [10] |

Troubleshooting Tip: When evaluating a novel MTA for ADC development, consider the Drug-Antibody Ratio (DAR) and linker stability. An suboptimal DAR or an unstable linker can lead to premature payload release and systemic toxicity, while a too-stable linker may reduce efficacy [10]. The ADC assembly process, whether via cysteine (Cys) or lysine (Lys) conjugation, can impact DAR homogeneity and pharmacokinetics [10].

FAQ 3: What are the classic, historically significant MTAs and their therapeutic origins?

Many foundational MTAs were derived from natural products and have been used for decades, treating conditions from cancer to inflammatory diseases [7] [9].

- Table 3: Historical Microtubule-Targeting Agents

| Drug Name | Source | Year of Key Discovery/Approval | Primary Historical Use | MTA Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colchicine | Autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale) | ~1500 BC (Ebers Papyrus) [7] | Gout, Inflammatory diseases [7] | Destabilizer (Colchicine site) |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) | 1971 (Isolation) [9] | Ovarian, Breast Cancer [9] | Stabilizer (Taxane site) |

| Vinblastine & Vincristine | Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) | 1960s (Approval) [9] | Leukemia, Lymphoma [9] | Destabilizer (Vinca site) |

Troubleshooting Tip: When using classical MTAs like vinca alkaloids or taxanes in cell-based assays, be aware of common off-target effects. A frequent issue is peripheral neuropathy, which is often linked to the disruption of microtubule-dependent axonal transport in neurons [11] [7]. In vitro, this can manifest as altered cell morphology and impaired vesicular trafficking even in non-mitotic cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for conducting research on microtubule-targeting agents.

- Table 4: Essential Reagents for MTA Research

| Research Reagent | Function in MTA Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Protein (e.g., from bovine brain) | In vitro polymerization assays; binding studies to characterize novel MTAs. | Purity is critical for consistent assay results. Requires GTP and suitable buffers for polymerization. |

| Cell Lines with MTA Resistance | To study resistance mechanisms (e.g., tubulin mutations, efflux pumps). | Commonly used: HeLa, A549, and their drug-resistant derivatives. Verify resistance profile regularly. |

| Immunofluorescence Staining Kits (Anti-α/β-Tubulin) | Visualize microtubule network morphology and mitotic spindles in fixed cells. | Choose validated, high-specificity antibodies. Confocal microscopy is recommended for detailed analysis. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay Kits | Rapidly screen thousands of compounds for effects on tubulin polymerization. | Available in fluorescence- or absorbance-based formats. Ideal for initial hit identification [14]. |

| Reporter Cell Lines | Screen for compounds that affect receptors or pathways using luminescence/fluorescence readouts [14]. | Engineered for robust signal output (e.g., luciferase). Useful for target-based or phenotypic screening. |

Diagram 2: Typical workflow for MTA identification.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my tubulin polymerization assay yielding inconsistent results for compounds targeting the Vinca domain?

- Answer: Inconsistent results with Vinca alkaloids are often due to their substoichiometric and concentration-dependent mechanism. At low concentrations, vinca alkaloids can suppress microtubule dynamics without depolymerizing them, while higher concentrations lead to microtubule disintegration.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Drug Concentration: Re-prepare drug stock solutions and perform a dose-response curve (e.g., 0.1 µM to 10 µM) to identify the optimal concentration for your assay system.

- Standardize Tubulin Source and Purity: Use a consistent, high-purity tubulin source (e.g., porcine brain tubulin) to minimize variability [1].

- Control Temperature and Assembly Time: Ensure the polymerization assay is performed at a consistent temperature (typically 37°C) and that readings are taken at the same time point after initiation.

- Include Appropriate Controls: Always include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) and a positive control (e.g., paclitaxel for polymerization, vinblastine for depolymerization).

FAQ 2: My colchicine-binding site inhibitor (CBSI) shows high potency in enzymatic assays but poor cellular efficacy. What could be the cause?

- Answer: This discrepancy is common and can arise from several factors:

- Cellular Penetration: CBSIs may have poor membrane permeability. Consider evaluating logP and performing a cell-based uptake assay.

- Efflux by Transporters: Many CBSIs are substrates for multidrug resistance (MDR) transporters like P-glycoprotein. Test efficacy in cell lines with and without MDR overexpression [15] [16].

- Serum Binding: The compound may be highly bound by serum proteins, reducing its free, active concentration. Repeat assays in the presence of serum.

- Binding Site Flexibility: The colchicine binding domain contains flexible loops (e.g., the βT7 loop) whose conformation is highly ligand-dependent, which can affect binding in the cellular context compared to the purified protein environment [15].

FAQ 3: What are the key considerations when designing an Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) using a maytansinoid payload?

- Answer: The primary goal is to enhance tumor specificity and reduce systemic toxicity.

- Linker Stability: The linker connecting the maytansinoid (e.g., DM1 or DM4) to the antibody must be stable in circulation but efficiently cleavable inside the target cancer cell (e.g., by lysosomal enzymes).

- Drug-to-Antibody Ratio (DAR): Optimize the DAR (typically 3-4) to maximize efficacy while maintaining good pharmacokinetics and low aggregation.

- Target Antigen Selection: The target antigen should be highly and uniformly expressed on tumor cells with minimal expression on healthy tissues.

- Payload Mechanism: Remember that maytansine inhibits microtubule assembly by binding to tubulin at the rhizoxin site, strongly suppressing microtubule dynamics and leading to mitotic arrest [17] [18].

FAQ 4: How does the stabilization mechanism of peloruside differ from that of paclitaxel, and how can I demonstrate this experimentally?

- Answer: While both are microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs), they bind to distinct sites and have different structural consequences.

- Mechanism: Paclitaxel binds the luminal taxane-site and can induce structural heterogeneity in the microtubule lattice. In contrast, peloruside binds a site on the microtubule exterior and acts primarily at lateral contacts, regularizing the lattice and even overriding the heterogeneity induced by paclitaxel in doubly-bound structures [19] [20].

- Experimental Demonstration:

- Competitive Binding: Perform a binding assay (e.g., a fluorescent anisotropy competition assay) to show that peloruside does not compete with a labeled taxane-site binder for tubulin binding.

- Structural Analysis: Use cryo-EM to compare microtubule structures stabilized by each drug. This can reveal the differences in lattice parameters and seam conformity [19].

- Combination Studies: Show that the combination of peloruside and paclitaxel has a synergistic effect on microtubule assembly and stability [19].

Quantitative Data on Tubulin Inhibitors

Table 1: Summary of Microtubule-Targeting Agents and Their Binding Sites

| Binding Site | Representative Drugs | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Structural Insights | Main Clinical Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinca Domain [21] | Vinblastine, Vincristine, Vinorelbine | Inhibits microtubule assembly by disrupting tubulin dimer addition and suppressing microtubule dynamics. | Binds to tubulin ends, inducing a "kinetic cap" that suppresses growth and shortening. Two high-affinity binding sites per tubulin dimer [21]. | Neutropenia (Vinblastine), Peripheral Neuropathy (Vincristine), Vesicant [21]. |

| Taxane Site [19] [22] | Paclitaxel (Taxol), Docetaxel, Zampanolide | Stabilizes microtubules, inhibits dynamics, and promotes assembly. | Binds to β-tubulin on the luminal side. Can induce lattice expansion and structural heterogeneity. Stabilizes the βM-loop to reinforce lateral contacts [19] [22]. | Peripheral Neuropathy, Neutropenia, Hypersensitivity reactions. |

| Colchicine Site [15] [16] | Colchicine, Nocodazole, Plinabulin | Inhibits microtubule assembly by preventing the curved-to-straight conformational transition of tubulin. | Binds at the interface of α- and β-tubulin. The flexible βT7 loop can adopt a "flipped-in" conformation that occludes the site in the absence of ligand [15]. | Gastrointestinal toxicity (Colchicine), Generally less susceptible to multidrug resistance [15]. |

| Maytansine Site [17] [18] | Maytansine (Maitansine), DM1, DM4 | Destabilizes microtubules by inhibiting assembly and strongly suppressing microtubule dynamics. | Binds to tubulin at the rhizoxin binding site. The binding mode has been characterized, showing it interacts with a specific site on β-tubulin [17]. | Systemic toxicity (parent compound); side effects are target-dependent when used as an ADC payload (e.g., T-DM1: thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity) [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Tubulin Polymerization Assay

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the effect of a compound on the kinetics of microtubule assembly in vitro. Reagents:

- Purified tubulin (>95% purity) [1]

- G-PEM buffer (80 mM PIPES pH 6.9, 2 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM GTP)

- Test compound dissolved in DMSO

- Vehicle control (DMSO)

- Positive control (e.g., Paclitaxel)

Methodology:

- Prepare a solution of tubulin (e.g., 3 mg/mL) in cold G-PEM buffer.

- Dispense the tubulin solution into a pre-chilled quartz cuvette or a multi-well plate.

- Add the test compound, positive control, or vehicle. Keep the final DMSO concentration consistent and low (typically <1%).

- Immediately place the cuvette/plate in a spectrophotometer or fluorometer (equipped with a temperature-controlled chamber) pre-warmed to 37°C.

- Continuously monitor the increase in turbidity (absorbance at 340 nm) or fluorescence (if using a reporter dye) for 60-90 minutes.

- Analyze the polymerization curves: Lag phase, growth rate (slope), and final plateau (polymer mass).

Protocol 2: Competitive Binding Assay using Fluorescence Anisotropy

Purpose: To determine if a test compound competes for binding with a known, fluorescently-labeled ligand at a specific site (e.g., the maytansine site). Reagents:

- Purified tubulin

- Fluorescent tracer (e.g., a fluorescently-labeled maytansinoid) [17]

- Test compounds

- Reference inhibitor (unlabeled maytansine)

Methodology:

- Prepare a fixed concentration of tubulin and the fluorescent tracer in an appropriate assay buffer.

- Titrate with increasing concentrations of the test compound or the reference inhibitor.

- Incubate the mixture to reach binding equilibrium.

- Measure the fluorescence anisotropy for each sample.

- Analyze the data: A decrease in anisotropy indicates that the test compound is displacing the fluorescent tracer from its binding site. Fit the data to a competitive binding model to calculate the inhibitory constant (Ki).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Tubulin Compound Screening

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Porcine Brain Tubulin [1] | High-purity tubulin for in vitro polymerization and binding assays. | The primary substrate for biochemical assays to directly measure compound effects on microtubule dynamics. |

| Fluorescent Tracers (e.g., for maytansine site) [17] | Enable binding affinity and competition measurements via fluorescence anisotropy. | Determining if a novel compound binds to the maytansine site by competing with the tracer. |

| Stabilized Microtubules | Used in spin-down assays or as substrates for motor protein ATPase assays. | Differentiating between compounds that disrupt existing microtubules versus those that only prevent new assembly. |

| Kinesin Motor Proteins (e.g., KIF18A) [1] | Targets for anti-mitotic drugs; used in ATPase activity assays. | Counter-screening to ensure compound specificity for tubulin and not mitotic kinesins. |

| T2R-TTL Tubulin Complex [22] | A stable tubulin complex used for X-ray crystallography of ligand-tubulin interactions. | Determining high-resolution crystal structures of tubulin in complex with taxanes or other small molecules. |

Mechanism and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Mechanism of microtubule-targeting drugs.

Diagram 2: Drug discovery workflow for cytoskeletal targets.

The cytoskeleton, a complex network of protein filaments, is a cornerstone of cellular integrity and function. For decades, it has been a validated target for chemotherapeutics, with drugs like taxanes and vinca alkaloids focusing on a limited set of well-characterized binding sites. However, the emergence of drug resistance and dose-limiting toxicities associated with these classical targets has underscored the urgent need for innovation. This technical support article frames this challenge within the broader context of cytoskeletal drug target compound screening, guiding researchers through the opportunities and technical pitfalls of exploring novel binding sites and underexplored cytoskeletal elements. We detail experimental protocols for targeting these emerging areas, provide troubleshooting guides for common assays, and list essential reagent solutions to equip scientists and drug development professionals with the tools for next-generation discovery.

FAQs: Novel Targets and Screening Strategies

1. What constitutes an "emerging" or "novel" binding site on the cytoskeleton?

Beyond the classical taxane, vinca alkaloid, and colchicine sites, recent research has identified and characterized several novel binding sites on tubulin. These include the sites for maytansine, laulimalide/peloruside A, pironetin, and the recently discovered gatorbulin binding site [23]. Targeting these sites can help overcome resistance mechanisms that have evolved against traditional microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs). Furthermore, the cytoskeleton's role has expanded into new biological contexts, such as the DNA damage response (DDR) and cellular reprogramming, revealing proteins like the Rho/ROCK effectors and YAP/TAZ as underexplored therapeutic targets in these pathways [24] [25].

2. Beyond microtubules, what other cytoskeletal elements are gaining traction as drug targets?

While microtubules remain a prime focus, other cytoskeletal components offer rich, underexplored territory:

- Actin and its Regulators: The actin cytoskeleton is critical in cancer metastasis, neuronal plasticity in substance use disorders, and cellular reprogramming [24] [26]. Key targets include upstream regulators like the Rho GTPase family (e.g., Rac1), their effectors (e.g., the WAVE and WASP complexes), and actin-binding proteins (ABPs) such as cofilin, profilin, and non-muscle myosin II (NmII) [27] [26].

- Tubulin Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): The "tubulin code," comprising modifications like detyrosination, is frequently altered in cancers and is linked to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. Targeting the enzymes that write, read, or erase these PTMs is a promising new strategy [28].

- Cytoskeleton-Mediated Mechanotransduction: Elements that translate mechanical forces into biochemical signals, such as the perinuclear actin cap and the Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex, are emerging as targets to influence nuclear shape, chromatin organization, and cell fate [24].

3. What are the primary technical challenges in screening compounds against these novel targets?

Screening for novel cytoskeletal targets presents unique challenges:

- Dynamic Instability: The inherent polymerization/depolymerization dynamics of filaments can make assay readouts highly variable.

- Functional Redundancy: The cytoskeleton is a dense network of interconnected filaments and binding proteins, leading to compensatory mechanisms that can mask phenotypic effects.

- Context-Dependent Effects: A compound's impact can vary dramatically based on cell type, extracellular matrix stiffness, and cell density, as these factors directly influence cytoskeletal organization and tension [24].

- Off-Target Effects: Many regulatory proteins, like small GTPases, have pleiotropic functions, making it difficult to attribute a phenotypic change to a single intended target.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Variability in Polymerization Assays

Problem: High well-to-well variability in in vitro tubulin or actin polymerization assays, leading to poor Z'-factors.

| Possible Cause & Solution | Protocol Adjustment |

|---|---|

| Cause: Inconsistent reagent temperatures. Tubulin polymerization is highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations. | Solution: Pre-warm all buffers, assay plates, and tubulin samples to the exact reaction temperature (typically 37°C) before initiating polymerization. Use a thermal cycler or water bath for precise control. |

| Cause: Unstable GTP/ATP supply. Depletion of nucleotide triphosphates (GTP for tubulin, ATP for actin) halts polymerization. | Solution: Include an ATP/GTP-regenerating system in the reaction buffer. For example, for tubulin, add phosphocreatine and creatine phosphokinase to maintain a constant GTP concentration. |

| Cause: Protein quality and purity. Contaminating nucleases or proteases can degrade reagents, and aggregated protein can seed non-physiological polymerization. | Solution: Use high-purity, fresh tubulin/actin. Centrifuge the protein sample at high speed (e.g., 100,000 x g) immediately before the assay to remove any pre-formed aggregates. |

Guide 2: Interpreting Complex Phenotypes in Cell-Based Screening

Problem: A hit compound from a phenotypic screen (e.g., on cell morphology) produces an unexpected or ambiguous cytoskeletal phenotype.

| Possible Cause & Solution | Follow-up Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cause: Off-target engagement on a related cytoskeletal element. A compound intended to inhibit a microtubule motor protein might also affect actin. | Solution: Multiplexed staining. Fix and stain cells for multiple cytoskeletal components simultaneously (e.g., microtubules [green], actin [red], and DNA [blue]). Analyze co-localization and overall architecture using high-content imaging. |

| Cause: Indirect effect via mechanotransduction. The compound may be affecting substrate adhesion or stiffness sensing, indirectly altering the cytoskeleton. | Solution: Check focal adhesions and nuclear shape. Stain for vinculin or paxillin to visualize focal adhesions. Examine nuclear shape irregularities, which can indicate disruption of the LINC complex or perinuclear actin cap [24]. |

| Cause: Activation of compensatory pathways. Inhibiting one cytoskeletal network may upregulate another. | Solution: Time-course and dose-response analysis. Monitor phenotypic changes over time and across a range of concentrations. A rapid effect may be direct, while a delayed effect suggests an indirect or compensatory mechanism. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Targeting the Actin Cytoskeleton - A Focus on Profilin and Membrane Interaction

This protocol outlines a method to investigate how small molecules modulate the interaction between the actin-binding protein profilin and membrane phosphoinositides, a key regulatory node in actin dynamics [27].

Principle: Profilin regulates actin polymerization by sequestering G-actin and promoting its addition to formin-bound filaments. Its activity is inhibited by binding to phosphoinositides like PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane. Compounds that disrupt this interaction can shift the balance of actin assembly.

Workflow Diagram: Profilin-Membrane Interaction Screening

Materials:

- Cell Line: HeLa or U2OS cells.

- Plasmids: Mammalian expression vector for human profilin-1 tagged with GFP.

- Lipid Vesicles: Synthetic liposomes containing a defined percentage of PI(4,5)P2.

- Key Reagents: See the "Research Reagent Solutions" table below.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells on glass-bottom 96-well plates at 50-60% confluence. Incubate for 24 hours.

- Transfection: Transfect cells with the Profilin-1-GFP plasmid using a standard lipofection method. Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow for expression.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with test compounds from your library for a predetermined time (e.g., 1-4 hours). Include controls (DMSO vehicle, known pathway activators like EGF).

- Stimulation (Optional): To dynamically assess profilin release, stimulate cells with an agent that hydrolyzes PI(4,5)P2, such as an agonist for Gq-coupled receptors or a calcium ionophore.

- Fixation and Imaging: At the endpoint, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Acquire high-resolution images using a confocal microscope.

- Image Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity of Profilin-GFP at the cell periphery (plasma membrane) versus the cytosol. A decrease in the membrane-to-cytosol ratio indicates compound-induced dissociation of profilin from the membrane.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Compounds Targeting Tubulin Detyrosination

This protocol describes a cell-based assay to identify compounds that modulate the tubulin detyrosination cycle, a promising PTM target [28].

Principle: Tubulin detyrosination, the removal of the C-terminal tyrosine of α-tubulin, is associated with stable microtubules and is linked to aggressive cancers. This assay uses immunofluorescence to detect levels of detyrosinated tubulin (Glu-tubulin) in compound-treated cells.

Workflow Diagram: Tubulin Detyrosination Compound Screen

Materials:

- Cell Line: Any adherent cancer cell line (e.g., A549, MCF-7).

- Antibodies: Primary antibody against detyrosinated tubulin (e.g., anti-Glu-tubulin). Primary antibody against total α-tubulin. Species-specific secondary antibodies with distinct fluorophores (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 and 555).

- Key Reagents: See the "Research Reagent Solutions" table below.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells in 96-well imaging plates. After 24 hours, treat with test compounds for a duration that allows for microtubule turnover (typically 6-24 hours).

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with pre-warmed 4% PFA for 15 min, then permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min.

- Immunostaining: Block cells with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. Incubate with primary antibodies (anti-Glu-tubulin and anti-α-tubulin) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Wash and incubate with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Include a nuclear counterstain (e.g., Hoechst).

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Image plates using a high-content imaging system. Using the analysis software, segment cells based on the nuclear stain and measure the mean fluorescence intensity for both the Glu-tubulin and total tubulin channels within the cytoplasmic region.

- Data Normalization: For each cell, calculate the ratio of Glu-tubulin intensity to total tubulin intensity. Normalize the average ratio per well to the DMSO control. Compounds that significantly decrease this ratio are potential inhibitors of the detyrosination enzyme (vasohibins) or activators of the tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL).

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table compiles key reagents essential for experiments targeting emerging cytoskeletal elements.

| Reagent Name | Target/Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor Phalloidin [29] | F-actin / Binds and stabilizes filamentous actin. | Essential for visualizing actin stress fibers, cortex, and other structures in fixed cells. Available in multiple fluorophores. |

| CellLight Tubulin-GFP/RFP, BacMam 2.0 [29] | Microtubules / Labels endogenous tubulin via baculovirus delivery. | Ideal for live-cell imaging of microtubule dynamics; provides uniform labeling with low cytotoxicity. |

| Recombinant Profilin Protein | Actin Nucleation / Regulates actin monomer availability and formin-mediated elongation. | Critical for in vitro polymerization assays to study compound effects on profilin-actin or profilin-membrane interactions [27]. |

| Anti-Glu-Tubulin Antibody | Detyrosinated Tubulin / Specifically recognizes the detyrosinated form of α-tubulin. | Key reagent for immunofluorescence-based screening of compounds affecting the tubulin detyrosination cycle [28]. |

| YAP/TAZ Antibody | Mechanotransduction / Nuclear effectors of the Hippo pathway, regulated by cytoskeletal tension. | Used to assess compound effects on mechanosignaling; monitor nuclear/cytoplasmic localization [24]. |

| RhoA/Rac1/CDC42 G-LISA Activation Assay | Small GTPase Activity / Measures levels of active, GTP-bound Rho GTPases. | Colorimetric or luminescent ELISA-based kit to quantitatively screen compounds targeting upstream regulators of actin. |

| Tubulin Polymerization Assay Kit | Microtubule Dynamics / Measures tubulin polymerization kinetics in vitro via fluorescence. | A standard biochemical HTS tool for characterizing direct microtubule stabilizers/destabilizers. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Landscape of Novel MTAs

The table below summarizes key quantitative data on established and emerging Microtubule-Targeting Agent (MTA) binding sites, providing a reference for screening outcomes and compound characterization [23].

| Binding Site Category | Representative Agents | Mechanism of Action | Development Status & Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxane-site Binders | Paclitaxel, Docetaxel | Microtubule Stabilization | Approved; limited by resistance (e.g., P-gp efflux, βIII-tubulin overexpression) and toxicity (neuropathy). |

| Vinca-site Binders | Vinblastine, Vincristine | Microtubule Destabilization | Approved; challenges include inherent and acquired resistance mechanisms. |

| Colchicine-site Binders | Combretastatin A-4 | Microtubule Destabilization | Orphan drug status; extensive research into novel analogs to improve pharmacokinetics. |

| Laulimalide/Peloruside | Laulimalide, Peloruside A | Microtubule Stabilization (novel site) | Preclinical; shows efficacy in taxane-resistant models but faces formulation challenges. |

| Maytansine-site Binders | Maytansine, DM1 | Microtubule Destabilization | DM1 is an ADC payload (Kadcyla); systemic use limited by toxicity. |

| Gatorbulin-site Binners | Gatorbulin-1 | Tubulin Degradation (novel mechanism) | Early preclinical; induces unique tubulin oligomers leading to proteasomal degradation. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in cytoskeletal drug target screening, providing practical solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

FAQ: Experimental Design and Model Selection

Q1: What are the key considerations when choosing between 2D and 3D cell culture models for cytoskeletal drug screening?

A1: The choice between 2D and 3D models significantly impacts your screening results and predictive validity.

- Traditional 2D Monolayers are suitable for initial high-throughput screening as they allow for rapid assessment of compound efficacy and cytotoxicity. However, they often overestimate compound effects and lack the physiological relevance of tumor microenvironments [30].

- 3D Spheroid Cultures better mimic solid tumor features, including structural organization, biological responses, gene expression patterns, and drug resistance mechanisms [30]. They develop distinct cellular layers:

Troubleshooting Tip: If your compound shows high efficacy in 2D cultures but fails in later-stage models, validate its activity in 3D spheroid cultures early in your screening pipeline. For instance, colchicine demonstrated potent activity in both 2D (IC~50~: 0.016-0.056 μM) and 3D AT/RT spheroid models (IC~50~: 0.004-0.023 μM), confirming its therapeutic potential across model systems [30].

Q2: How can I address differential chemosensitivity in my cancer cell models during screening?

A2: Differential chemosensitivity is a common challenge that can be leveraged to understand compound mechanisms.

- Strategy: Intentionally use cell lines with known differential sensitivity profiles. For example, in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) screening, BT-12 cells (chemosensitive) and BT-16 cells (chemoresistant) provide a valuable system for identifying compounds that can overcome resistance mechanisms [30].

- Implementation: Screen compounds in parallel across sensitive and resistant lines. Compounds maintaining efficacy in resistant lines may target alternative pathways or bypass common resistance mechanisms.

Troubleshooting Tip: When encountering inconsistent results across cell lines of the same cancer type, characterize their genetic backgrounds (e.g., SMARCB1 deficiency in AT/RT cells) and establish baseline sensitivity to reference cytoskeletal agents (vinca alkaloids, taxanes) to create internal reference standards [30].

FAQ: Technical Implementation and Optimization

Q3: What controls and validation steps are critical for high-throughput screening of cytoskeletal targets?

A3: Rigorous quality control is essential for generating reliable screening data.

- Control Setup: Implement stringent controls including:

- Positive controls: Known cytoskeletal agents (vincristine, paclitaxel, colchicine)

- Negative controls: Vehicle-only treatments (DMSO)

- Cell viability controls: Untreated cells for normalization [30]

- Validation Metrics: Use statistical quality parameters like Z'-factor >0.5 to ensure robust assay performance and minimize false positives/negatives.

- Secondary Validation: Follow primary screening with dose-response studies to determine IC~50~ values and assess cytotoxicity in relevant normal cells (e.g., human brain endothelial cells and astrocytes) to establish therapeutic windows [30].

Q4: How can I optimize blood-brain barrier penetration for neurological indications?

A4: BBB penetration remains a significant challenge for CNS-targeted cytoskeletal drugs.

- Compound Selection: Prioritize compounds with molecular properties conducive to BBB penetration (lower molecular weight, appropriate lipophilicity). Some microtubule-targeting agents like colchicine show favorable selectivity indices (>2 orders of magnitude) between tumor cells and normal brain cells [30].

- Delivery Strategies: Consider advanced delivery systems including nanoparticles, liposomes, and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that can enhance CNS delivery while minimizing systemic exposure [31].

- Mechanistic Considerations: Evaluate effects on interphase microtubules rather than just antimitotic activity, as this may provide therapeutic benefits in neurological disorders with reduced neurotoxicity [32] [33].

Troubleshooting Tip: If promising compounds show poor BBB penetration in preclinical models, explore structural analogs or prodrug strategies that maintain cytoskeletal targeting while improving brain bioavailability.

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening for Cytoskeletal-Targeting Compounds

This protocol outlines a robust framework for screening compound libraries against cytoskeletal targets [30] [34].

- Compound Library Preparation: Prepare stock plates (384-, 1536-, or 3456-well formats) of your compound library. Use liquid handling devices to transfer compounds to assay plates [34].

- Cell Culture and Plating:

- Maintain relevant cell lines (e.g., BT-12 and BT-16 for AT/RT) under standard conditions

- Seed cells in assay-compatible plates at optimized densities for 2D (traditional monolayers) or 3D (spheroid) cultures [30]

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with test compounds (e.g., 10 μM initial concentration), positive controls (doxorubicin, known cytoskeletal agents), and vehicle controls [30].

- Viability Assessment: After appropriate incubation (typically 72 hours), measure cell viability using optimized detection methods (fluorescence intensity, luminescence, colorimetry) [34].

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Use plate readers capable of high-throughput detection

- Normalize data to positive and negative controls

- Identify "hit" compounds that inhibit viability by >80% compared to controls [30]

- Perform dose-response curves for confirmed hits to determine IC~50~ values

Troubleshooting Tip: For 3D spheroid cultures, ensure uniform spheroid size and quality before compound treatment, as size variability can significantly impact compound penetration and response metrics [30].

Protocol 2: Validating Cytoskeletal-Targeting Mechanisms

This protocol confirms whether hit compounds directly target cytoskeletal components [32] [33].

- Immunofluorescence Microscopy:

- Treat cells with compounds at relevant concentrations (IC~50~-IC~80~) for 4-24 hours

- Fix, permeabilize, and stain with antibodies against tubulin (microtubules), actin (microfilaments), or relevant cytoskeletal proteins

- Include markers for DNA to assess mitotic arrest and cellular morphology

- Image using high-content or confocal microscopy

- In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay:

- Incubate purified tubulin with test compounds in polymerization-promoting buffer

- Monitor microtubule formation turbidimetrically (350nm) over time at 37°C

- Compare polymerization kinetics to vehicle controls and reference agents (paclitaxel for stabilizers, vincristine/colchicine for destabilizers)

- Binding Site Characterization:

- Perform competition assays with fluorescently-labeled reference compounds (e.g., colchicine-site, vinca-site binders)

- Use structural biology approaches (crystallography, cryo-EM) for definitive binding site identification

Troubleshooting Tip: If immunofluorescence shows cytoskeletal disruption but in vitro tubulin assays are negative, investigate potential indirect mechanisms through kinase inhibition (MARK4, GSK3β) or effects on microtubule-associated proteins [35].

Table 1: Efficacy Profiles of Selected Cytoskeletal-Targeting Compounds in Preclinical Models

| Compound | Primary Target | Cancer Model efficacy (IC~50~) | Neurological Indication | Therapeutic Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colchicine | Tubulin (colchicine site) [32] | 0.016-0.056 μM (AT/RT, 2D) [30]0.004-0.023 μM (AT/RT, 3D) [30] | Gout, Pericarditis [32] | >357-fold (vs. astrocytes) [30] |

| Eribulin | Tubulin (vinca site) [32] | Breast cancer, Liposarcoma (clinical) [32] | - | Reverses EMT, improves survival [32] |

| Vinca Alkaloids | Tubulin (vinca site) [32] | Hematological malignancies (clinical) [32] | - | Dose-limiting neurotoxicity [33] |

| Taxanes | Tubulin (taxane site) [33] | Solid tumors (clinical) [33] | Under investigation [31] | Limited by neurotoxicity [33] |

Table 2: Advanced Cytoskeletal-Targeting Modalities in Development

| Therapeutic Approach | Mechanism | Therapeutic Indications | Advantages | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (e.g., T-DM1) [32] | Antibody-targeted delivery of maytansinoid DM1 | HER2+ breast cancer [32] | Targeted delivery, reduced systemic toxicity | FDA-approved [32] |

| PROTACs targeting CDKs [36] | Targeted protein degradation of cell cycle regulators | Various cancers [36] | Overcomes resistance, catalytic action | Preclinical/clinical development [36] |

| MARK4 Inhibitors [35] | Inhibition of tau hyperphosphorylation | Alzheimer's disease [35] | Addresses specific neurodegenerative mechanism | Preclinical identification [35] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Cytoskeletal Drug Target Screening

| Reagent / Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines with Differential Sensitivity | Identifying compounds that overcome resistance | BT-12 (chemosensitive) vs. BT-16 (chemoresistant) AT/RT cells [30] |

| 3D Spheroid Culture Systems | Mimicking solid tumor architecture and drug resistance | Layered spheroids with proliferative, quiescent, and necrotic zones [30] |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Quantifying cytoskeletal and morphological changes | Immunofluorescence analysis of microtubule, actin organization [32] [33] |

| Tubulin Polymerization Assays | Direct assessment of microtubule dynamics | In vitro turbidimetric measurements of microtubule formation [32] |

| OATP Transporter Models | Evaluating cellular uptake mechanisms | OATP1B1/1B3 (hepatic), OATP1A2 (BBB) transporters for MC-LR uptake [37] |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

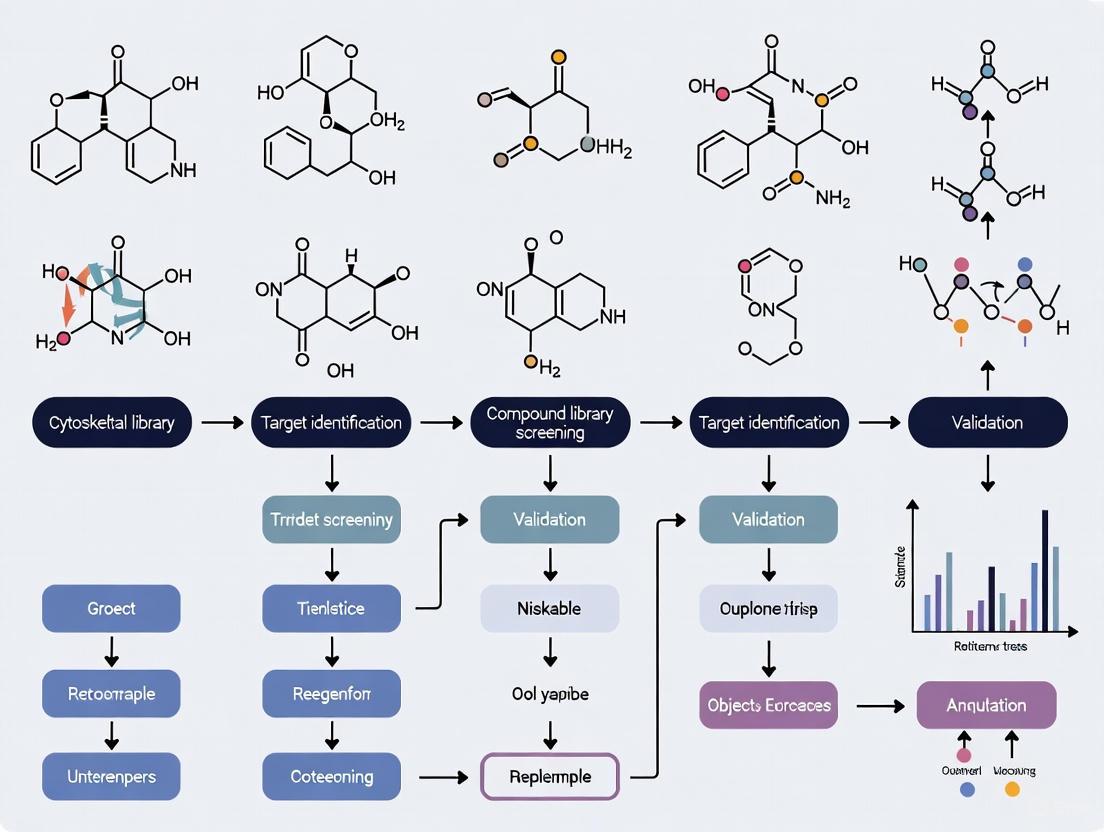

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Screening Workflow for Cytoskeletal-Targeting Compounds. This diagram outlines the key stages in identifying and validating compounds that target the cytoskeleton, from initial screening through mechanistic validation [30].

Diagram 2: Cytoskeletal Dysregulation in Neurodegeneration and Therapeutic Targeting. This pathway illustrates how cytoskeletal stressors lead to neuronal dysfunction and identifies key intervention points for cytoskeletal-targeting therapies [38] [35].

Screening Technologies and Assay Platforms: From Biochemical to Complex Physiological Systems

What is the fundamental principle behind an in vitro tubulin polymerization assay? The assay is an economical and convenient extracellular method that monitors the polymerization of tubulin into microtubules over time under controlled conditions. As tubulin polymerizes, the increasing mass of microtubules in solution changes its optical properties. This change can be measured either by an increase in turbidity (absorbance) or by an increase in the fluorescence of a reporter dye that incorporates into the growing microtubule structures. The resulting polymerization curve allows researchers to qualitatively judge compound binding and quantitatively analyze inhibitory or promotive activity on tubulin polymerization [39].

How is this assay used in drug discovery? In vitro tubulin polymerization is a primary screen for identifying and characterizing Microtubule Targeting Agents (MTAs). It confirms whether a compound directly affects tubulin and determines its mode of action—stabilizing/polymerizing or destabilizing/depolymerizing [40]. The assay is crucial for determining half-maximal effective or inhibitory concentration values (EC₅₀/IC₅₀) and for establishing structure-activity relationships (SAR) during lead compound optimization [39] [41].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Fluorescence-Based Protocol

This protocol uses a commercially available kit (e.g., Cytoskeleton, Inc. BK011P) and is designed for high-throughput screening [42].

- Principle: A fluorescent reporter dye binds to tubulin and emits a strong signal upon incorporation into the microtubule polymer. Fluorescence intensity increases as polymerization proceeds [42].

- Materials:

- Purified tubulin (>99% pure)

- Tubulin buffer with a fluorescent reporter

- GTP (Guanosine triphosphate)

- Tubulin glycerol buffer

- Control compounds (e.g., Paclitaxel, Vinblastine)

- Half-area 96-well or 384-well black, flat-bottom microtiter plates

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reconstitution: Prepare all reagents according to the kit's datasheet, keeping them on ice.

- Reaction Setup: In a well, combine tubulin protein, fluorescent reporter, and GTP in the appropriate tubulin polymerization buffer. The typical final volume is 50 µL for a 96-well format or 10 µL for a 384-well format.

- Compound Addition: Add the test compound to the reaction mix. Include controls: a no-compound control, a polymerization enhancer control (e.g., paclitaxel), and a polymerization inhibitor control (e.g., vinblastine).

- Data Acquisition: Immediately transfer the plate to a temperature-controlled fluorimeter pre-heated to 37°C. Record the fluorescence intensity (Ex: 360 nm / Em: 420 nm) every minute for 60-90 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence versus time to generate polymerization curves for each condition.

Absorbance (Turbidity)-Based Protocol

- Principle: Polymerization of tubulin into microtubules increases the turbidity of the solution, which can be measured as an increase in optical density (OD) [39].

- Materials:

- Purified tubulin (often from mammalian brain)

- MES or PEM buffer system

- GTP

- Glycerol (often used at 15-20% to promote polymerization)

- Clear 96-well plates

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare tubulin in a glycerol-containing polymerization buffer (e.g., MES buffer with 15% glycerol) and keep it on ice [39] [42].

- Reaction Setup: Pipette the tubulin solution into a well. Add test compound or vehicle control.

- Data Acquisition: Transfer the plate to a temperature-controlled plate reader at 37°C. Monitor the absorbance at 350 nm (A350) every minute for 60-90 minutes [39].

- Data Analysis: Plot OD350 versus time. The slope of the curve indicates the rate of polymerization, and the plateau indicates the total mass of polymer formed.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow common to both types of assays.

Quantitative Data and Assay Performance

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics for a standard fluorescence-based tubulin polymerization assay [42].

Table 1: Standard Assay Performance Metrics for a Fluorescence-Based Tubulin Polymerization Assay

| Parameter | Specification / Value | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Method | Fluorescence (360 nm Ex / 420 nm Em) | |

| Tubulin Purity | >99% | Essential for reliable, reproducible results [42]. |

| Assay Throughput | 96-well or 384-well format | 50 µL (96-well) or 10 µL (384-well) reaction volume [42]. |

| Key Control EC₅₀/IC₅₀ | Paclitaxel EC₅₀: 0.49 µMVinblastine IC₅₀: 0.6 µM | Under standard kit conditions [42]. |

| Assay Variability | Coefficient of Variation (CV): ~11% | Indicates good reproducibility [42]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

We observe a low signal-to-noise ratio or a flat polymerization curve in both control and test samples. What could be wrong? This is typically caused by loss of tubulin activity.

- Cause 1: Improper handling or storage. Tubulin is a labile protein. Always keep it on ice and use glycerol-containing buffers for stability. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles [39].

- Solution: Use fresh, high-purity tubulin. Confirm that positive controls (e.g., paclitaxel) are working. If they fail, the tubulin lot is likely compromised.

- Cause 2: Inaccurate temperature control. Polymerization is highly temperature-sensitive and requires a precise and rapid shift to 37°C [39].

- Solution: Pre-heat the fluorimeter or plate reader to 37°C and ensure the plate equilibrates quickly. Verify the instrument's temperature calibration.

The positive control (e.g., Paclitaxel) works, but our test compound shows high variability between replicates. This often points to issues with compound solubility and preparation.

- Cause: Many discovery compounds are dissolved in DMSO, which can affect tubulin dynamics at high concentrations. Precipitation can lead to inconsistent exposure.

- Solution: Ensure the final concentration of DMSO is consistent and low (typically ≤1%) across all samples, including controls. Centrifuge compound stocks to remove insoluble particles before use.

The shape of our polymerization curve is abnormal, with a sudden drop in signal mid-experiment. This suggests microtubule instability after formation.

- Cause: Physical disturbance of the plate or temperature fluctuations during the reading phase can cause microtubules to depolymerize.

- Solution: Ensure the plate reader is in a stable location, free from vibrations. Confirm that the temperature is maintained consistently at 37°C throughout the entire run.

We get different results when testing the same compound in cell-based assays. Why? This is a common disconnect between in vitro and cell-based readouts.

- Cause 1: The compound may not be cell-permeable.

- Cause 2: The compound might be metabolized or sequestered in the cellular environment.

- Cause 3: Cellular factors, such as Microtubule-Associated Proteins (MAPs) or different tubulin isotypes, can modulate the compound's effect [41]. A positive in vitro result confirms the compound can target pure tubulin, suggesting follow-up live-cell imaging experiments are needed [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Tubulin Polymerization Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Assay |

|---|---|

| Purified Tubulin | The core substrate of the assay. High purity (>99%) is critical for reliable results and is typically purified from mammalian brain or recombinant sources [42] [40]. |

| Nucleotides (GTP) | Provides the energy source necessary for the polymerization reaction. It is an essential component of the polymerization buffer. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Microtubule-stabilizing control compound. Used as a positive control to promote polymerization and validate assay performance [39] [42]. |

| Vinblastine / Colchicine | Microtubule-destabilizing control compounds. Used as positive controls to inhibit polymerization. They bind to distinct sites on tubulin (vinca and colchicine sites, respectively) [42] [43]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Dye | A dye that exhibits enhanced fluorescence upon binding to polymerized microtubules, enabling real-time, quantitative tracking of polymerization in fluorescence-based assays [42]. |

| Glycerol | A common component of polymerization buffers that promotes and stabilizes microtubule formation by reducing the critical concentration of tubulin required for polymerization [39] [42]. |

Advanced Techniques and Emerging Methods

Are there more advanced methods to study compound effects on tubulin? Yes, beyond standard fluorescence and absorbance assays, several advanced techniques provide deeper mechanistic insights.

- Nano-Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (nanoDSF): This innovative label-free method monitors the intrinsic fluorescence of tubulin's tryptophan residues during a temperature ramp. It provides a dual readout: it can detect compound binding through tubulin thermostabilization (change in melting temperature, Tm) and simultaneously determine the compound's functional effect on the apparent polymerization temperature (Tpoly). This makes it highly valuable for discriminating between different mechanisms of action [41].

- Mechanistic Binding Site Competition Assays: These assays determine if a novel compound binds to a known site (e.g., taxane, vinca, or colchicine sites). They involve measuring the polymerization kinetics of tubulin in the presence of both the novel compound and a well-characterized site-specific inhibitor. If the novel compound's effect is abolished, it likely binds to the same site [40].

- Live-Cell Imaging: Following in vitro confirmation, this technique validates that the compound engages its target in a physiologically relevant context, disrupting the microtubule cytoskeleton and causing phenotypic changes like cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase [40] [43].

Mechanistic Binding Site Competition Assays

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle of a competitive binding assay? A competitive binding assay measures how an unlabeled analyte (like a drug candidate) competes with a labeled reagent for a limited number of binding sites on a target protein. The core principle is that the amount of labeled analyte bound to the target is inversely proportional to the concentration of the competing unlabeled analyte. When the concentrations of the antibody and labeled analyte are constant, the bound labeled analyte decreases as the concentration of the competitive, unlabeled analyte increases [44].

2. Why would my assay show high background signal or poor curve fit? High background or poor data fitting in assays like Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) can often be traced to compound-related issues. Common culprits include intrinsic fluorescence of the test compound, interactions between the compound and the fluorescent dye, or poor compound solubility leading to aggregation. These factors can produce irregular melt curves that are difficult to interpret [45].

3. My compound shows binding in a biochemical assay but not in a cellular one. What could be wrong? A positive result in a biochemical assay (e.g., using purified protein) that fails to translate to a cellular assay (like CETSA) often points to a cell membrane permeability issue. The test compound must efficiently cross the cell membrane to bind its intracellular target. If the compound cannot enter the cell, no stabilization or destabilization of the target protein will be observed, despite confirmed binding in a cell-free system [45].

4. How do I calculate the binding affinity (Ki) of my unlabeled compound? The inhibitory constant (Ki) for an unlabeled ligand is not measured directly but is calculated from a competition experiment. First, you must determine the dissociation constant (Kd) between your target and a fluorescently labeled competitor. Then, you titrate your unlabeled ligand against a pre-formed complex of the target and the labeled competitor to determine the EC50 (the concentration that displaces 50% of the labeled ligand). The Ki can then be calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff equation: Ki = EC50 / (1 + [C]t / Kd,C + [T]t / Kd,T), where [C]t and [T]t are the total concentrations of the labeled competitor and target, respectively [46].

5. What are the major advantages of label-free binding assays? Techniques like Thermal Shift Assays (TSAs) and Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) are label-free, meaning neither the drug compound nor the target protein needs to be modified with a fluorescent or radioactive tag. This avoids the risk of the label altering the binding characteristics of the molecule. DARTS, for example, is cost-effective, can be applied to unmodified small molecules, and does not require large quantities of pure protein [45] [47].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irregular or noisy melt curves (DSF) | Compound-dye interactions; compound autofluorescence [45]. | Test compound intrinsic fluorescence beforehand; use a control with compound and dye only [45]. |

| No thermal shift observed | No binding; incorrect buffer conditions; protein already aggregated [45]. | Ensure protein is stable and soluble in chosen buffer; include a positive control ligand [45]. |

| Low signal in competition assays | Insufficient complex formation; labeled ligand concentration too high [46]. | Use target concentration ~1-2x its Kd with the labeled competitor; keep labeled ligand concentration at or below its Kd [46]. |

| High variability between replicates | Protein aggregation or precipitation; inconsistent sample preparation [45]. | Include low concentrations of non-ionic detergents (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20) to improve protein stability [45]. |

| Positive in lysate but not in whole cells (CETSA) | Poor cell permeability of the compound [45]. | Confirm compound permeability; use lysate-based TSAs (PTSA/DSF) as an intermediate step [45]. |

Table 2: Key Buffer and Reagent Considerations

| Parameter | Consideration | Impact on Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Composition | Additives like detergents or viscosity agents can interfere with fluorescent dyes [45]. | Can cause high background fluorescence or quenched signals [45]. |

| Protein Quality | Protein must be stable, soluble, and not pre-aggregated before the assay [45]. | Unstable protein leads to poor melt curves and unreliable Tm shifts [45]. |

| Labeled Ligand Purity | The purity and specific activity of the labeled antigen are critical for assay accuracy [44]. | Impurities can lead to inaccurate quantification and reduced sensitivity [44]. |

| Loading Control (PTSA) | Use a highly heat-stable protein like SOD1 or APP-αCTF for normalization [45]. | Ensures accurate quantification of the target protein band during densitometry [45]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Competitive Binding Assay with Fluorescent Tracer

This protocol outlines the steps to determine the Ki of an unlabeled ligand by competing it with a fluorescently labeled molecule [46].

Step 1: Determine the Kd of the Labeled Competitor

- Setup: Prepare a titration series of the unlabeled target protein.

- Reaction: Incubate each target concentration with a constant, low concentration of the fluorescent competitor (at or below its expected Kd).

- Measurement: Use a compatible method (e.g., fluorescence anisotropy, TR-FRET) to measure the fraction of bound competitor.

- Analysis: Fit the dose-response data to the law of mass action to extract the Kd for the labeled competitor-target interaction [46].

Step 2: Competition Experiment to Determine EC50

- Setup: Prepare a titration series of the unlabeled ligand of interest.

- Reaction: In each reaction, include a constant concentration of the target (sufficient to form a complex, ~1-2x Kd from Step 1) and a constant concentration of the labeled competitor (same as in Step 1). Add the titrated unlabeled ligand.

- Measurement: Measure the signal corresponding to the bound labeled competitor. As the unlabeled ligand concentration increases, the signal will decrease.

- Analysis: Fit the resulting data with a sigmoidal dose-response curve (Hill equation) to determine the EC50 value [46].

Step 3: Calculate the Ki

Use the Cheng-Prusoff equation to calculate the Ki for your unlabeled ligand:

Ki = EC50 / (1 + [C]t / Kd,C + [T]t / Kd,T)

Where:

- EC50 is from Step 2.

- [C]t is the total concentration of the labeled competitor used in Step 2.

- Kd,C is the dissociation constant for the competitor from Step 1.

- [T]t is the total concentration of the target used in Step 2 [46].

Protocol 2: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

CETSA evaluates target engagement in a more biologically relevant cellular context [45].

- Sample Preparation: Plate cells according to the desired experimental setup. Treat cells with the test compound or vehicle control for a specified time to allow for cellular uptake and target binding.

- Heating: Aliquot the cell suspensions (intact cells or cell lysates) and heat each aliquot at different temperatures (e.g., from 40°C to 65°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 3 minutes).

- Protein Quantification: Lyse the heated cells (if using intact cells) and separate the soluble protein from aggregates by centrifugation. Quantify the remaining soluble target protein in each sample using Western blot or other immunoassays.

- Data Analysis: Plot the fraction of soluble protein remaining against the temperature. Fit the data to generate melt curves. A rightward shift in the melting temperature (Tm) in the compound-treated sample indicates stabilization and direct binding of the compound to the target protein [45].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Competitive Binding Principle

Competitive Binding Assay Workflow

TSA Progression in Drug Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Binding Site Competition Assays | Example Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Protein | The target molecule for biochemical binding studies. High purity and stability are critical [45]. | DSF, PTSA, competitive binding with fluorescent tracer [45]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Provide high specificity for a single epitope, essential for immunometric and detection assays [44]. | Western blot detection in CETSA/PTSA; engineered polyclonal mixtures for complex targets [44] [45]. |

| Polarity-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., SyproOrange) | Bind hydrophobic patches exposed upon protein unfolding; core detection reagent in DSF [45]. | High-throughput screening of compound libraries using DSF [45]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled Ligands | Serve as the competing tracer molecule in fluorescence-based competitive binding assays [46]. | Determining Kd and EC50 values for Ki calculations [46]. |

| Heat-Stable Loading Control Proteins (e.g., SOD1) | Used for normalization in PTSA to account for sample-to-sample variation [45]. | Ensuring accurate quantification of target protein bands in gel-based thermal shift assays [45]. |

| Cytoskeletal Target Proteins | Specific proteins relevant to cytoskeletal research for specialized screening [48]. | Tubulin polymerization assays; kinesin ATPase assays; myosin activity screens [48]. |

Cell Painting is a high-content, image-based morphological profiling assay that utilizes multiplexed fluorescent dyes to comprehensively characterize cell state in an unbiased manner. By simultaneously labeling multiple cellular components, it generates rich, quantitative data describing cellular morphology, enabling researchers to detect subtle phenotypic changes resulting from genetic or chemical perturbations [49] [50]. This technique is particularly powerful for cytoskeletal drug target compound screening, as it can capture complex phenotypic signatures induced by compounds affecting tubulin, actin, myosin, and other cytoskeletal targets, providing insights into their mechanism of action (MoA) without prior knowledge of the specific target [48] [51] [52].

The assay employs six fluorescent dyes imaged in five channels to reveal eight broadly relevant cellular components: the nucleus, nucleoli, cytoplasmic RNA, the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus, the actin cytoskeleton, and the plasma membrane [49] [53] [50]. Automated image analysis software then identifies individual cells and extracts ~1,500 morphological features (measuring size, shape, texture, intensity, and spatial relationships) to create a morphological "fingerprint" or profile for each treated cell population [49] [50] [54]. These profiles can be compared to suit various goals in drug discovery, including identifying the phenotypic impact of chemical perturbations, grouping compounds into functional pathways based on biosimilarity, and identifying signatures of disease [49] [50] [51].

For cytoskeletal research, Cell Painting offers a distinct advantage. It can identify compounds with a shared MoA, such as cell-cycle modulation, even when they have different annotated protein targets or are structurally diverse [51] [52]. This is crucial for discovering compounds that target non-protein biomolecules or exhibit polypharmacology. Furthermore, the assay can be used to build performance-diverse small-molecule libraries for phenotypic screening, enriching for compounds that produce measurable morphological effects in a specific cell type [50].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Cell Painting Assay

Detailed Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for a Cell Painting experiment, from cell plating to data analysis:

Protocol Duration: The entire process, from cell culture to data analysis, typically takes 2 to 4 weeks [49] [53].

Step 1: Cell Plating

- Plate cells in multiwell plates (typically 96- or 384-well format) at an appropriate confluency to ensure isolated cells for accurate segmentation [49] [54]. U-2OS cells are commonly used due to their large, flat morphology and good adherence, but the protocol can be adapted to other cell lines [51].

- Critical Consideration: Include appropriate controls (e.g., vehicle controls, positive control compounds) and account for potential edge effects in the plates [49].

Step 2: Treatment/Perturbation

- Perturb cells with the treatments to be tested (e.g., small molecules from a cytoskeleton-focused library [52]) for a desired duration, often 24-48 hours [49] [54]. A typical concentration range includes multiple doses (e.g., 2 μM, 10 μM) to assess phenotypic concentration dependence [51].

Step 3: Staining and Fixation

- After treatment, cells are fixed, permeabilized, and stained with the multiplexed dye set. The original and updated Cell Painting protocols specify the following stains [49] [53]:

- Hoechst 33342: Labels DNA in the nucleus.

- Concanavalin A conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488: Labels the endoplasmic reticulum.

- Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555: Labels the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus.

- Phalloidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 or 568: Labels filamentous actin (F-actin).

- SYTO 14 green fluorescent RNA stain: Labels nucleoli and cytoplasmic RNA.

- MitoTracker Deep Red: Labels mitochondria.

- Protocol Update (Cell Painting v3): Recent optimizations have shown that concentrations for some stains (e.g., Phalloidin, WGA, Concanavalin A) can be reduced without compromising data quality, lowering assay cost [53].

Step 4: Image Acquisition

- Image the stained plates on a high-throughput or high-content screening (HCS) microscope capable of automated imaging in five fluorescence channels [49] [54].

- Acquire multiple fields per well to ensure a statistically significant number of cells are captured for analysis.

Step 5: Image Analysis and Feature Extraction

- Use automated image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler [49] [53], Cellpose [53]) to identify individual cells and their subcellular compartments.

- The software extracts ~1,500 morphological features per cell, quantifying various aspects of size, shape, texture, intensity, and spatial correlations between channels [49] [50] [54].

Step 6: Data Analysis and Profiling

- Generate population-level morphological profiles from the single-cell data.

- Use data processing tools (e.g., Pycytominer [53]) and clustering algorithms to compare profiles across different perturbations. Compounds or genes with similar morphological impacts will cluster together, suggesting a shared MoA [50] [51].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required to perform a Cell Painting assay.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for the Cell Painting Assay

| Item | Function in the Assay | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dyes | Multiplexed staining of 8 cellular components. | Hoechst 33342 (DNA), Phalloidin (F-actin), WGA (Golgi/PM), ConA (ER), MitoTracker (Mitochondria), SYTO 14 (RNA) [49] [53] [54]. |

| Cell Painting Kit | Pre-optimized reagent set for convenience. | Image-iT Cell Painting Kit (Thermo Fisher) provides all dyes in pre-measured amounts [54]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automated image acquisition of multi-well plates. | Systems like the CellInsight CX7 LZR Pro are designed for high-throughput fluorescence imaging [54]. |

| Image Analysis Software | Cell segmentation and feature extraction. | CellProfiler [49] [53] is an open-source standard; Cellpose [53] is a powerful alternative. |

| Data Analysis Tools | Processing and clustering morphological profiles. | Pycytominer [53] for data normalization and aggregation; KNIME [53] for workflow integration. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can Cell Painting specifically benefit cytoskeletal drug discovery? Cell Painting is exceptionally well-suited for cytoskeletal research because it directly visualizes and quantifies changes in cellular structures. It can group compounds based on their phenotypic impact, identifying novel microtubule, actin, or myosin regulators even without prior target knowledge [51] [52]. For instance, it can cluster iron chelators with S/G2 phase cell-cycle regulators based on their shared morphological fingerprint, revealing a common MoA rooted in impaired cell division [51].