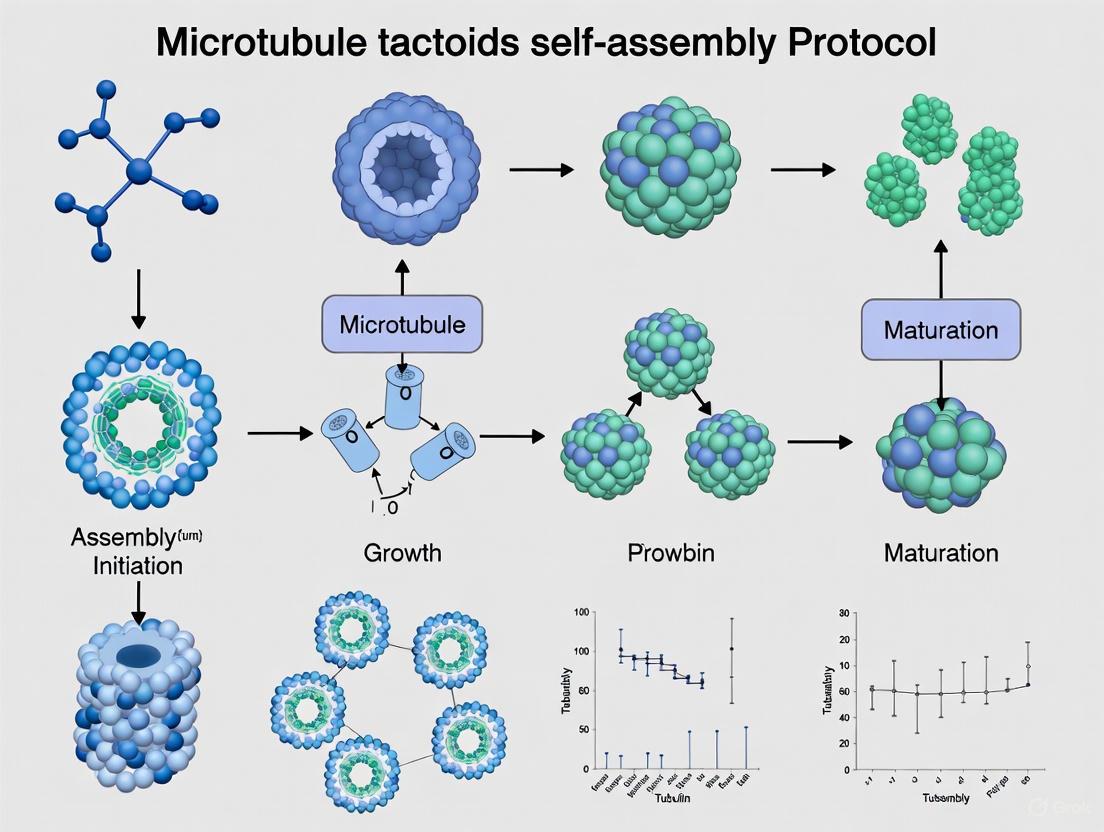

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Microtubule Tactoids Self-Assembly: From Reconstitution to Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the self-assembly of microtubule tactoids, which are spindle-shaped, liquid crystal-like structures that serve as minimalistic in vitro models for...

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Microtubule Tactoids Self-Assembly: From Reconstitution to Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the self-assembly of microtubule tactoids, which are spindle-shaped, liquid crystal-like structures that serve as minimalistic in vitro models for the mitotic spindle. It details a proven protocol utilizing the antiparallel crosslinker MAP65 and crowding agents to reconstitute these structures from a minimal set of components. The scope covers the foundational principles of tactoid formation, a step-by-step methodological pipeline, essential troubleshooting and optimization strategies based on recent research, and robust techniques for validating the assemblies through fluorescence microscopy and Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP). This resource is tailored for professionals in biophysics and drug development seeking to implement this technique in their labs for studying cytoskeletal organization and screening potential therapeutic targets.

Understanding Microtubule Tactoids: Biological Significance and Liquid Crystal Principles

The mitotic spindle is a transient, complex machinery essential for cell division via mitosis and meiosis, responsible for the accurate segregation of genetic material [1] [2]. This structure is primarily composed of microtubule filaments—dynamic polymers of tubulin dimers with a high aspect ratio and significant stiffness—organized into specific architectures by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) and motor proteins [2].

The spindle contains distinct microtubule populations: kinetochore microtubules that connect spindle poles to chromosome kinetochores, and interpolar microtubules that grow past chromosomes and overlap at the spindle's central midzone [2]. A third type, astral microtubules, extends from the poles to the cell cortex and is outside the scope of this discussion [2]. The physical organization of short, dynamic, and overlapping microtubule arrays, particularly in meiotic spindles, gives these structures properties similar to liquid crystal tactoids [2]. These spindle-like shapes arise from the local alignment of asymmetric molecules or structures into a nematic phase, a property shared by the high local concentration of microtubules in the spindle [2].

Table 1: Key Features of the Mitotic Spindle

| Feature | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Segregate chromosomes during cell division [2] | Ensures accurate genetic inheritance |

| Main Structural Element | Microtubules (tubulin polymers) [2] | Provides structural framework and force-generation machinery |

| Key Microtubule Types | Kinetochore, Interpolar, Astral [2] | Facilitates chromosome attachment, spindle stability, and positioning |

| Liquid Crystal Properties | Similar to a bipolar tactoid [2] | Suggests physical mechanisms contribute to self-organization |

The Rationale for In Vitro Models

Studying the mitotic spindle directly within living cells is complex due to the vast number of interconnected biochemical and physical variables. In vitro reconstitution provides a powerful alternative by simplifying the system to its core components, allowing for precise dissection of the mechanisms underlying spindle assembly and function [3].

A major goal of in vitro approaches is to understand how self-organization emerges from a minimal set of components. The cytoskeleton performs major internal reorganization without central direction, especially during mitosis [1] [2]. In vitro models enable researchers to test how specific proteins, such as antiparallel crosslinkers or molecular motors, contribute to the formation of bipolar structures from an initially disordered state [2] [4].

These models are also indispensable for functional analysis. For instance, the Xenopus laevis egg extract system allows for the direct inhibition of specific proteins via immunodepletion or dominant-negative constructs to analyze their mitotic function [3]. Similarly, isolated diatom spindles can be reactivated in vitro to study the energy requirements and mechanics of anaphase spindle elongation [5]. Ultimately, well-characterized in vitro systems serve as critical platforms for screening and drug discovery, enabling the identification of compounds that modulate spindle dynamics, which is relevant for cancer therapy [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Key In Vitro Models for Studying the Mitotic Spindle

| Model System | Key Components | Applications and Insights | Example Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xenopus Egg Extracts | Meiotic cytoplasm, sperm nuclei or chromatin beads [3] [4] | Study of spindle assembly pathways, function via protein inhibition, and anaphase [3] | Sawin & Mitchison, 1991 [4] |

| Isolated Diatom Spindles | Pre-formed spindles isolated from cells [5] | Analysis of ATP-dependent spindle elongation and microtubule dynamics in anaphase B [5] | Cande & McDonald, 1985 [5] |

| Minimal Systems (e.g., Tactoids) | Purified tubulin, crosslinkers (MAP65), crowding agents [1] [2] | Investigation of physical principles of self-organization and minimal requirements for spindle-like shapes [2] | JoVE Protocol, 2022 [1] |

Pathways of Mitotic Spindle Assembly In Vitro

Research using in vitro models, particularly Xenopus egg extracts, has revealed multiple pathways for spindle assembly. One study identified two distinct pathways dependent on the cell cycle state of the extract when sperm nuclei are introduced [4].

In the first pathway, sperm nuclei added to metaphase-arrested extracts direct the assembly of polarized half-spindles. These half-spindles subsequently fuse pairwise to form bipolar spindles [4]. In the second pathway, sperm nuclei are introduced to extracts that are first induced to enter interphase and are then arrested in the subsequent mitosis. In this case, a single sperm nucleus can direct the assembly of a complete bipolar spindle [4]. A key finding from this work is that while microtubule arrays are strongly biased towards chromatin, the establishment of stable bipolar arrays does not strictly depend on specific kinetochore-microtubule interactions in either pathway [4]. This suggests a hierarchy of selective microtubule stabilization involving chromatin-microtubule and antiparallel microtubule-microtubule interactions [4].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and key differences between these two assembly pathways.

The Microtubule Tactoid Model: A Minimal System

The microtubule tactoid model represents a minimalist approach to reconstituting spindle-like structures. This system aims to recreate the spindle's shape and some physical properties using a highly reduced set of components, focusing on the role of antiparallel microtubule crosslinking and macromolecular crowding [2].

The core insight behind this model is that microtubules, as mesoscale objects with high stiffness and a high aspect ratio, can be treated as scaled-up versions of liquid crystal molecules (mesogens) [2]. The meiotic spindle's behavior, including its ability to coalesce and merge, aligns with the properties of a liquid crystal tactoid—a nematic phase that nucleates and grows from an isotropic state [2]. The characteristic spindle shape arises because the asymmetric microtubules cannot form a rounded crystal when they align [2].

Successful formation of these tactoids requires specific conditions:

- Short Microtubules: Achieved by nucleating and stabilizing filaments with GMPCPP, a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog, to prevent dynamic instability and end-to-end annealing [2].

- Antiparallel Crosslinker: MAP65, a plant microtubule-associated protein and a homolog of mammalian PRC1 and yeast Ase1, is used to self-organize microtubules into spindle-like assemblies [1] [2] [6].

- Crowding Agent: Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is included to create depletion forces that increase the local concentration of microtubules and favor bundle formation [2].

A key advantage of this minimal system is that it is highly reproducible and accessible, requiring only purified components rather than complex biological extracts [7]. It serves as a bridge, connecting biological organization to the principles of soft matter physics [2] [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Microtubule Tactoid Assembly

The following table details the essential reagents and their functions for recreating the microtubule tactoid assembly in vitro.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Microtubule Tactoid Assembly

| Reagent | Function and Purpose | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin | Core structural protein for microtubule polymerization [2] [7] | Often a mix of unlabeled and rhodamine-labeled tubulin for visualization [7] |

| MAP65 | Antiparallel microtubule crosslinker [1] [2] | Plant homolog of PRC1/Ase1; can be tagged with GFP for visualization [2] [7] |

| GMPCPP | Nucleates and stabilizes short microtubules [2] | A non-hydrolyzable GTP analog that caps microtubule ends [2] |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Crowding agent [2] | Creates depletion interactions that promote microtubule condensation and bundling [2] |

| Glucose Oxidase/Catalase | Oxygen-scavenging system [7] | Prevents photodamage during fluorescence microscopy [7] |

| Pluronic F-127 | Non-ionic block copolymer surfactant [2] [7] | Coats chamber surfaces to prevent non-specific microtubule adhesion [2] [7] |

Detailed Protocol for Microtubule Tactoid Assembly and Analysis

This protocol is adapted from the JoVE video article "Self-Assembly of Microtubule Tactoids" [2] [7].

Tubulin Preparation

- Obtain an aliquot of unlabeled tubulin (1 mg lyophilized powder) from -80°C storage and keep it on ice.

- Resuspend the unlabeled tubulin in 200 µL of cold PEM-80 buffer. Keep on ice for 10 minutes to dissolve completely.

- Obtain a tube of rhodamine-labeled tubulin (20 µg lyophilized powder) from -80°C storage and keep it on ice.

- Resuspend the labeled tubulin in 4 µL of cold PEM-80 buffer. Keep on ice for 10 minutes.

- Combine 100 µL of the resuspended unlabeled tubulin with the 4 µL of resuspended rhodamine-labeled tubulin. Mix by pipetting slowly 6-7 times.

- Aliquot the tubulin mix into seven tubes (15 µL each), flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C for future use [7].

Flow Chamber Assembly

- Clean a glass slide thoroughly with double-distilled water and ethanol, then dry it with a lint-free wipe.

- Create two thin strips from double-sided tape and place them on the slide 5-8 mm apart.

- Place a silanized coverslip on top of the tape strips to create the flow path.

- Seal the chamber by gently pressing on the tape area with the back of a pen until the tape turns clear.

- Trim excess tape from the edges, leaving about 1 mm at the chamber entrance, and label the chamber [7].

Tactoid Assembly Reaction

- Thaw all reagents on ice and keep them on ice throughout the procedure.

- Coat the flow chamber with 20 µL of 5% Pluronic F-127 in PEM-80. Incubate in a humid chamber for 5-7 minutes.

- In a sterile tube on ice, mix the following components by pipetting 5-6 times:

- PEM-80 buffer

- GMPCPP

- Pluronic F-127

- Dithiothreitol (DTT)

- Glucose

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

- The prepared tubulin mix

- MAP65 (with GFP-MAP65 for visualization)

- Add 1 µL of a pre-mixed glucose oxidase and catalase solution to the tubulin-MAP mixture. Mix by pipetting 7-8 times.

- Remove the Pluronic solution from the flow chamber by capillary action using a lint-free wipe at one end.

- Immediately add the tubulin-MAP mixture to the chamber entrance to draw it inside.

- Seal both ends of the chamber with five-minute epoxy.

- Incubate the chamber at 37°C for 30 minutes to nucleate and grow microtubule tactoids [7].

Imaging and Analysis

- Use a fluorescence microscope with a 60x or higher magnification objective and a numerical aperture (NA) of 1.2 or greater.

- Maintain the sample at 37°C during imaging using an environmental chamber or stage heater.

- For rhodamine-labeled tubulin, use a 561 nm laser with at least 1 mW of power at the sample.

- For GFP-MAP65, use a 488 nm laser for excitation.

- Acquire at least 10 images from different areas to capture over 100 tactoids. Save images as 16-bit TIFF files for analysis [7].

- To characterize constituent mobility, perform Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP). For microtubules in tactoids, no fluorescence recovery is typically observed, indicating a solid-like state. For MAP65, fluorescence recovers gradually, indicating mobility, and can be fit to a rising exponential decay to find the amplitude and time scale of recovery [2] [7].

The experimental workflow for the entire protocol, from preparation to analysis, is summarized below.

What are Liquid Crystal Tactoids? Bridging Soft Matter Physics and Cell Biology

Liquid crystal tactoids are anisotropic microdroplets that spontaneously nucleate from an isotropic dispersion and represent a transition state before forming a macroscopic liquid crystalline phase [8] [9]. First observed in vanadium pentoxide sols by Zocher in 1925, these spindle-shaped or spherical birefringent microdroplets have since been identified in numerous lyotropic liquid crystalline systems including tobacco mosaic viruses, cellulose nanocrystals, carbon nanotubes, and various biological systems [8] [9]. Tactoids form through a process of microscopic phase separation when local concentration reaches a critical threshold, creating discrete ordered microdomains within a continuous disordered phase [8] [10]. What makes tactoids particularly fascinating to soft matter physicists and cell biologists alike is their ability to exhibit long-range orientational order while maintaining fluidity, a combination that enables complex structural transformations through coalescence, sedimentation, and response to external fields [8] [11].

The fundamental formation process of tactoids relies on a balance between competing forces: attractive interactions that gather mesogens into microdroplets and repulsive forces that arrange them into liquid crystalline order [8]. These interactions are often modeled using the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory, where electrostatic repulsion between charged mesogens balances with long-range van der Waals attraction [8]. According to Onsager theory, the critical concentration for phase separation decreases with increasing aspect ratio of rod-like mesogens, meaning tactoids preferentially form in microdomains rich in high-aspect-ratio particles [8]. This selective nucleation process enables tactoids to function as molecular sorting mechanisms in both synthetic and biological systems.

Tactoids in Biological Systems

Microtubule Tactoids and Cell Division

The cytoskeleton exemplifies nature's utilization of liquid crystal principles, particularly during cell division when microtubules form the mitotic spindle without central direction [12]. This self-organizing process mirrors the behavior of liquid crystal tactoids, where microtubules function as mesoscale mesogens that assemble into spindle-like configurations [12] [1]. The meiotic spindle especially resembles a liquid crystal tactoid, containing short, dynamic microtubules that overlap in networked arrays [12]. This structural similarity has inspired researchers to reconstitute microtubule tactoids in vitro using minimal components, providing crucial insights into how cells might orchestrate such complex structural transformations without centralized control [12].

Microtubules possess inherent characteristics that make them ideal candidates for liquid crystalline organization: they are significantly longer than they are wide (high aspect ratio), exhibit substantial stiffness, and can align through steric and electrostatic interactions [12]. In the cellular environment, these properties enable microtubules to behave as scaled-up versions of liquid crystal molecules, following similar physical principles of phase transitions, nucleation, and growth [12]. The discovery that microtubules can form tactoids in vitro suggests that biological systems may exploit these fundamental soft matter principles to achieve complex organizational tasks.

Actin and Other Biological Tactoids

Beyond microtubules, tactoid formation has been observed in other crucial biological systems. Filamin has been shown to cause actin to condense into tactoids, suggesting similar liquid crystal principles may govern the organization of multiple cytoskeletal components [9]. Additionally, filamentous bacteriophage Pf4 generates a tactoid shell around host P. aeruginosa cells that confers antibiotic resistance [9]. These diverse biological examples demonstrate that tactoid formation is not merely a laboratory curiosity but a fundamental organizational strategy employed across biological systems.

Table 1: Biological Systems Exhibiting Tactoid Formation

| Biological System | Structural Role | Key Organizing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Microtubule Spindles | Chromosome segregation during cell division | MAP65/Ase1/PRC1 crosslinkers, molecular crowding [12] |

| Actin Bundles | Cytoskeletal organization, mechanical stability | Filamin crosslinking, concentration thresholds [9] |

| Filamentous Phage Pf4 | Bacterial biofilm assembly, antibiotic resistance | Viral particle self-assembly at cell surface [9] |

Quantitative Characterization of Tactoids

Shape and Size Parameters

Tactoids exhibit predictable relationships between their size, shape, and internal structure. Experimental studies using β-lactoglobulin amyloid fibrils and cellulose nanocrystals have revealed that tactoids with smaller volumes (approximately 10² μm³) typically maintain a homogeneous configuration, while medium-sized tactoids (approximately 10³ μm³) often transition to a bipolar structure, and larger tactoids (approximately 10ⴠμm³) frequently develop cholesteric configurations with characteristic striped textures [11]. The aspect ratio (α = R/r, where R is the major semi-axis and r is the minor semi-axis) decreases with increasing volume, creating a predictable size-shape relationship [13].

The shape of tactoids is determined by the competition between surface energy, which favors spherical droplets, and elastic energy of the liquid crystalline phase, which promotes elongation [8]. For smaller tactoids, an additional competition emerges between surface energy and anchoring energy caused by deviation of the director field at the boundary from preferred orientation [8]. This delicate balance results in tactoids exhibiting spindle-like, prolate, or oblate shapes with different internal structures depending on their size and mesogen characteristics [8].

Relaxation Dynamics

The relaxation behavior of tactoids following deformation follows predictable exponential decay patterns. Research has demonstrated that shape relaxation, characterized by the parameter Ʀ = (R(t) - Requil)/(Rinit - Requil), follows a single exponential decay across all tactoid classes: Ʀ = exp(-t/τs) [11]. The characteristic shape relaxation time (τs) can be expressed as the sum of liquid crystalline anisotropic contributions (τa) and characteristic shape relaxation time of elongated isotropic tactoids (τ_i) [11]:

τs = b[ω/(ckBT(2K/K2 - 1)^(1/2)Mφ^(1/4)MQ^(3/4)ξ^(1/2)) + (βμI)/(bγ)]R_equiv

where K and K2 are elastic constants, Mφ and MQ are mobility parameters, ξ is the correlation length, μI is the isotropic viscosity, and γ is the interfacial tension [11].

Table 2: Characteristic Parameters of Different Tactoid Classes

| Tactoid Class | Typical Volume (μm³) | Aspect Ratio Range | Director Field Configuration | Relaxation Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogeneous Nematic | ~10² | Higher | Uniform alignment parallel to long axis | Single exponential decay [11] |

| Bipolar Nematic | ~10³ | Intermediate | Director follows interface with defects at poles | Single exponential decay [11] |

| Uniaxial Cholesteric | ~10â´ | Lower | Helical structure with periodic bands | Second-order exponential decay [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Microtubule Tactoid Self-Assembly Protocol

The following protocol enables the formation and study of microtubule tactoids in vitro using a minimal set of components, based on established methodologies [12] [1]:

Silanization of Cover Glasses

- Safety Note: Perform all steps in a fume hood while wearing appropriate protective equipment due to toxic silane vapors.

- Rinse cover glasses sequentially with ddHâ‚‚O, 70% ethanol, and ddHâ‚‚O to remove dust and soluble particles.

- Dry between rinses with lint-free laboratory wipes.

- Place cover glasses in a metal rack and expose to dimethyl-dichloro-silane vapor in a desiccator for 30 minutes.

- Bake silanized cover glasses at 110°C for 10 minutes to complete the process.

Preparation of Microtubules

- Use tubulin dimers purified from mammalian brain tissue or recombinant sources.

- Polymerize tubulin using GMPCPP (a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog) to nucleate and stabilize microtubules.

- Critical Step: Ensure microtubules are short (controlled length distribution) by regulating nucleation conditions and growth time.

- Stabilize resulting microtubules against dynamic instability and end-to-end annealing.

Formation of Tactoids

- Combine stabilized short microtubules with MAP65 (antiparallel microtubule crosslinker from plants) in appropriate buffer.

- Include PEG (crowding agent) to create depletion interactions that enhance local concentration.

- Incubate mixture between silanized cover glasses at room temperature for 30-60 minutes.

- Monitor tactoid formation using polarized light microscopy or fluorescence microscopy.

Characterization Methods

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Image tactoid shapes using fluorescently labeled microtubules.

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP): Assess mobility of components within tactoids.

- Polarized Light Microscopy: Visualize birefringence patterns to determine internal director field.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for microtubule tactoid assembly and characterization.

Capture and Stabilization of Tactoids in Solid Matrices

Studying the fine structure of tactoids has been challenging due to their highly deformable, fluid nature. Recent advances enable capturing these structures in solid matrices for detailed examination [8] [10]:

- Photopolymerization Method: Introduce cross-linked polyacrylamide matrices into the tactoid system.

- Rapid Polymerization: Initiate using UV light or chemical catalysts to quickly stabilize tactoid structures.

- Electron Microscopy: Examine captured tactoids using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at resolutions sufficient to identify individual mesogens.

- Cross-section Analysis: Create fracture surfaces perpendicular to each other to examine chiral nematic structures from multiple angles.

This approach has revealed that small tactoids often exhibit unwound nematic structure with uniformly aligned cellulose nanocrystals, while larger tactoids develop left-handed helical chiral nematic structures appearing as series of flat periodic bands, each representing a half-helical pitch [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microtubule Tactoid Research

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MAP65 (Ase1/PRC1) | Antiparallel microtubule crosslinker | Plant-derived; essential for spindle-like assembly [12] |

| GMPCPP | Non-hydrolyzable GTP analog | Nucleates and stabilizes microtubules; controls length [12] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Crowding agent | Creates depletion interactions; enhances local concentration [12] |

| Dimethyl-dichloro-silane | Hydrophobic surface treatment | Enables polymer brush coating on cover glasses [12] |

| Tubulin Dimers | Structural protein | Purified from mammalian brain or recombinant sources [12] |

| β-lactoglobulin Amyloid Fibrils | Model rod-like colloids | Used for liquid crystalline phase studies [11] [13] |

| Cellulose Nanocrystals | Model rod-like colloids | Used for chiral nematic phase studies [8] [11] |

| Cabotegravir | Cabotegravir, CAS:1264720-72-0, MF:C19H17F2N3O5, MW:405.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, CAS:1085711-35-8, MF:C22H22O12, MW:478.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Flow-Induced Order-Order Transitions

Recent research has revealed that tactoids undergo fascinating structural transformations under flow conditions. When subjected to extensional flow in microfluidic devices, tactoids align and deform, undergoing order-order transitions at critical elongation thresholds [13]. Bipolar and cholesteric tactoids transform into homogeneous configurations when sufficiently extended, with the cholesteric pitch decreasing as an inverse power-law of the tactoid aspect ratio [13]. These flow-induced transformations provide insights into how biological systems might control structural organization through mechanical forces and confinement.

Microfluidic approaches with hyperbolic contraction zones enable precise control over extension rates (typically 0.004-0.020 sâ»Â¹ for amyloid fibril tactoids), allowing researchers to observe how tactoids respond to defined flow fields [13]. This methodology has revealed that tactoids align parallel to flow during extension, then rotate approximately 90° to perpendicular alignment after exiting extension zones, exhibiting behaviors similar to other anisotropic colloidal particles [13].

Nanoparticle Separation and Magnetic Manipulation

Liquid crystalline tactoids exhibit remarkable size-selective exclusion effects on foreign nanoparticles, providing a potential mechanism for nanoparticle separation [10]. Experiments with polymer nanospheres, gold nanoparticles, and paramagnetic nanoparticles have demonstrated that tactoids selectively incorporate particles below a threshold size while excluding larger particles [10]. This principle enables size-based separation where smaller nanoparticles are transported from disordered to ordered phases during phase separation.

When paramagnetic nanoparticles are added to systems containing tactoids, the disordered phases develop higher volume magnetic susceptibility due to preferential nanoparticle exclusion from tactoids [10]. This property enables control of tactoid movement and orientation using gradient magnetic fields as weak as several hundred Gauss/cm, potentially allowing researchers to direct phase separation rates, configurations, and director field orientations [10].

Figure 2: Tactoid applications in nanoparticle separation and magnetic control.

Liquid crystal tactoids represent a fascinating convergence of soft matter physics and biological organization principles. Their ability to self-assemble, transform, and respond to environmental cues makes them ideal model systems for understanding how biological systems achieve complex organization without central direction. The experimental protocols outlined here, particularly for microtubule tactoids, provide researchers with robust methodologies to explore these structures in controlled settings.

Future research directions will likely focus on harnessing tactoid properties for advanced materials design, drug delivery systems, and organizational principles in synthetic biology. The ability to control tactoid formation, transformation, and interaction with nanoparticles suggests numerous applications in biosensing, materials separation, and biomimetic material design. As our understanding of these remarkable structures deepens, we anticipate increasing convergence between fundamental soft matter research and biological applications, potentially revealing new principles of self-organization across length scales.

The cytoskeleton is a prime example of self-organization within the cell, achieving complex structural changes without central direction. This is particularly evident during cell division, where microtubules (MTs) form the mitotic spindle to segregate genetic material. Microtubule tactoids are spindle-shaped, self-organized assemblies that serve as minimal in vitro models for studying the physical principles underlying spindle formation [2] [12]. These structures recapitulate the bipolar morphology of the spindle midzone and are nucleated through a carefully balanced interplay of core biochemical components. The self-assembly process is driven by a minimal system comprising tubulin, antiparallel microtubule crosslinkers from the MAP65/PRC1/Ase1 family, and macromolecular crowding agents [2]. This application note details the protocols and quantitative data essential for reconstituting these structures, providing researchers with a toolkit for investigating cytoskeletal self-organization.

The Key Players: Components and Functions

Tubulin: The Structural Monomer

Tubulin, a heterodimeric protein, is the fundamental building block of microtubules. The kinetics of its polymerization are critical for tactoid formation.

- Self-Assembly Kinetics: Traditional one-dimensional (1D) models of microtubule growth assume a constant subunit dissociation rate. However, recent high-resolution studies using TIRF microscopy and laser tweezers have demonstrated that the tubulin subunit dissociation rate from a microtubule tip actually increases with free tubulin concentration [14]. This results in much faster on-off kinetics than previously estimated—an order of magnitude higher—and must be considered when modeling tactoid assembly.

- Microtubule Length Control: For successful tactoid formation, short microtubules are essential [2]. Long microtubules typically form extended bundles rather than finite, tapered tactoids. To obtain short, stable microtubules, the protocol recommends nucleating filaments with GMPCPP, a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog that suppresses dynamic instability and end-to-end annealing, resulting in a high density of short seeds for self-assembly [2].

MAP65/PRC1/Ase1: The Antiparallel Crosslinker

The MAP65/PRC1/Ase1 family of microtubule-associated proteins are the primary architects defining the architecture of microtubule tactoids.

- Function as Antiparallel Crosslinkers: These proteins are dimeric and specifically crosslink microtubules in an antiparallel orientation [2]. This activity is crucial for organizing microtubules into the bipolar, spindle-like shape of a tactoid, mirroring their role in forming the central spindle midzone during anaphase in cells [15].

- Liquid Condensate Formation: Recent findings indicate that MAP65 and its homolog PRC1 can undergo phase separation to form biomolecular condensates under physiological conditions, even without added crowding agents [16]. These condensates can nucleate and grow microtubule bundles. The size of the resulting microtubule asters is directly controlled by the concentration of MAP65, highlighting a potential mechanism for regulating intracellular organization [16].

- Regulatory Network: The activity of these crosslinkers is finely tuned by a post-translational modification network involving key kinases such as Cdk1, Plk1, and Cdc14, which ensures their function is restricted to the correct stage of cell division [15].

Crowding Agents: Creating the Physiochemical Environment

Macromolecular crowding agents are indispensable for recreating the dense cytoplasmic environment in vitro.

- Depletion Forces: Crowding agents like polyethylene glycol (PEG) create an "excluded volume" effect, which generates entropic (depletion) forces that promote microtubule bundling and condensation [17] [2]. This effect is critical for concentrating tubulin and MAP65 to the thresholds required for tactoid nucleation.

- Acceleration of Kinetics: Crowding dramatically accelerates biochemical reactions. In the case of microtubule growth, the presence of crowding agents can increase the apparent rate constant for tubulin addition by up to 10-fold [17]. When combined with regulatory enzymes like XMAP215 and EB1, crowding agents can push microtubule growth rates to approximately 45 μm/min at 10 μM tubulin, approaching the theoretical maximum and observed physiological rates [17].

Table 1: Key Components for Microtubule Tactoid Assembly

| Component | Key Function | Critical Considerations for Protocol Design |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin | Structural monomer for microtubule polymerization | Use GMPCPP to generate short, stable seeds. Net growth rate increases with free tubulin concentration, but dissociation rate also rises [14]. |

| MAP65/PRC1/Ase1 | Antiparallel microtubule crosslinking | Concentration controls organization; low levels yield tactoids, high levels can form condensates that nucleate asters [2] [16]. |

| Crowding Agent (e.g., PEG) | Induces bundling via depletion forces & accelerates growth | Strength of attractive force and system density favor formation of extensile nematic networks over asters [17] [18]. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Parameters

Successful self-assembly of microtubule tactoids depends on precise control over component concentrations and environmental conditions. The following tables consolidate key quantitative parameters from foundational studies.

Table 2: Effects of Crowding Agents and MAP65 on Microtubule Growth and Organization

| Experimental Condition | Observed Effect on Microtubules | Quantitative Measurement / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding (PEG) + XMAP215 + EB1 | Synergistic acceleration of growth | Growth rates saturate near ~45 μm/min at 10 μM tubulin [17]. |

| Crowding Agent Alone | Increased tubulin addition rate | Apparent rate constant for tubulin addition increased up to 10-fold [17]. |

| MAP65 Crosslinking | Formation of finite, spindle-shaped tactoids | Requires short MTs; forms solid-like, birefringent, homogeneous tactoids [2]. |

| High [MAP65] / PRC1 | Formation of phase-separated condensates | Condensates nucleate MT bundles/asters; can be liquid-like (gelating over time) [16]. |

| Varying Ionic Strength | Modulation of MAP65-MT binding and organization | High salt shifts tactoids to unbounded bundles; reduces but does not eliminate MAP65 binding [16]. |

Table 3: Optimized Concentration Ranges for Tactoid Self-Assembly

| Parameter | Recommended Range / Value | Notes and Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Concentration | 0.5 - 2.0 μM (for growth) | Higher concentrations increase net growth but also dissociation fluctuations [14]. |

| MAP65 Concentration | Low, precisely titrated | Critical for tactoid shape; high concentrations promote large-scale aster formation [2] [16]. |

| Crowding Agent (PEG) | Variable, system-dependent | Strength of depletion attraction controls transition from asters to extensile bundles [18]. |

| Microtubule Length | Short (stabilized with GMPCPP) | Essential for tapered tactoids; long filaments form unbounded bundles [2]. |

| Ionic Strength | Physiological, but can be manipulated | Increased salt disrupts electrostatic interactions, affecting tactoid finiteness [16]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the steps for forming microtubule tactoids, with special emphasis on surface preparation to prevent non-specific adhesion and allow for proper microscopic observation.

Coverslip Silanization and Chamber Preparation

NOTE: Perform these steps in a fume hood while wearing appropriate personal protective equipment. Dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) is highly toxic [2].

- Cleaning: Rinse coverslips sequentially with ddHâ‚‚O, 70% ethanol, and ddHâ‚‚O. Dry them with lint-free laboratory wipes between each rinse.

- UV-Ozone Cleaning: Place coverslips in a metal rack and transfer to a UV-Ozone (UVO) machine. Irradiate for 20 minutes to remove organic contaminants and reduce background fluorescence. (A plasma cleaner can be used as an alternative.)

- Solvent Rinsing: Using tweezers, transfer the coverslips to a dedicated silanization rack.

- Immerse the rack in 100% acetone for 1 hour. Rinse the container 3x with tap water and 3x with ddHâ‚‚O.

- Immerse the rack in 100% ethanol for 10 minutes. Rinse the container 3x with tap water and 3x with ddHâ‚‚O.

- Base Wash: Immerse the rack in 0.1 M KOH for 15 minutes. Rinse the container thoroughly 3x with tap water and 3x with ddHâ‚‚O.

- Final Water Rinse: Immerse the rack in ddHâ‚‚O three times for 5 minutes each.

- Drying: Air-dry the rack with coverslips overnight in a fume hood or laminar flow hood.

- Silanization: After complete drying, immerse the rack and coverslips in 2% dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) in a dedicated container for 5 minutes.

- Ethanol Rinse: Immerse the rack and coverslips twice in 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each.

- Curing: Air-dry the coverslips again. The silanized coverslips are now ready for creating a flow chamber and subsequent polymer brush coating to create a non-adhesive passivated surface for imaging [2].

Tactoid Self-Assembly Reaction

- Prepare Tubulin Solution: Mix tubulin in a general tubulin buffer (e.g., 80 mM PIPES pH 6.8-7.0, 1 mM EGTA, 1-2 mM MgClâ‚‚). For short, stable microtubules, include GMPCPP to nucleate and stabilize filaments against dynamic instability [2].

- Initiate Assembly: Combine the prepared tubulin solution with the antiparallel crosslinker MAP65 and a crowding agent (e.g., PEG) in the appropriate buffer.

- Incubate: Allow the reaction mixture to incubate at room temperature or a defined physiological temperature (e.g., 25-37°C) for a sufficient period (typically 30-60 minutes) for tactoids to nucleate and grow.

- Image: Transfer an aliquot of the reaction to a passivated imaging chamber and analyze using fluorescence microscopy. For characterization of shape and internal dynamics, employ:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Experiment | Example Source / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Protein (various species) | Core structural monomer for microtubule polymerization. | Porcine brain, human (e.g., MCF-7 cells), plant (soybean), fungi (Agaricus bisporus) [19]. |

| GMPCPP | Non-hydrolyzable GTP analog; nucleates and stabilizes short microtubules. | Jena Bioscience; used to prevent dynamic instability and annealing [2]. |

| MAP65 / PRC1 / Ase1 | Antiparallel microtubule crosslinking protein; defines bipolar tactoid shape. | Recombinant protein (e.g., from plant MAP65-1, human PRC1) [2] [16]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Macromolecular crowding agent; induces depletion-induced bundling. | Common molecular weights: 5-20 kDa [17] [2]. |

| PIPES Buffer | Standard buffer for tubulin and microtubule experiments; maintains pH. | 80 mM PIPES, pH 6.8-7.0, with 1 mM EGTA, 1-2 mM MgClâ‚‚ [19]. |

| Taxol / Paclitaxel | Microtubule-stabilizing drug; used in some protocols to suppress dynamics. | Cytoskeleton Inc.; often used at low micromolar concentrations [19]. |

| Silanized Coverslips | Hydrophobic surface for subsequent polymer brush coating to prevent adhesion. | Prepared in-lab with dimethyldichlorosilane [2]. |

| VU0420373 | VU0420373, MF:C15H11FN2O, MW:254.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Atopaxar hydrobromide | Atopaxar hydrobromide, CAS:943239-67-6, MF:C29H39BrFN3O5, MW:608.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Molecular Regulation of the Ase1/PRC1/MAP65 Family

The following diagram summarizes the key regulatory inputs that control the activity of the central crosslinkers in this family, such as PRC1, during cell division.

Diagram 1: Regulatory network of PRC1 family proteins.

Workflow for Microtubule Tactoid Self-Assembly

This flowchart outlines the major experimental steps for successfully creating and analyzing microtubule tactoids, from reagent preparation to data collection.

Diagram 2: Microtubule tactoid self-assembly workflow.

The Role of Short, Stable Microtubules and Antiparallel Crosslinking in Shape Determination

The self-organization of microtubules into specific, functional architectures is a fundamental process in cell division, polarity, and motility. Central to this process is the formation of the mitotic spindle, a structure that shares remarkable geometric similarity with liquid crystal tactoids. These spindle-like assemblies can be reconstituted in vitro using a minimal set of components: short, stable microtubules and specific antiparallel microtubule crosslinkers from the MAP65/PRC1/Ase1 family [20] [1]. The interplay between microtubule length and crosslinking activity is critical for determining the final shape and mechanical properties of these cytoskeletal structures. This application note details the quantitative relationships and experimental protocols that underpin the role of these components in shape determination, providing a resource for researchers aiming to reconstitute and study these architectures.

Core Principles: Geometry and Crosslinking in Shape Determination

The Mechanistic Role of Antiparallel Crosslinkers

Proteins such as PRC1 (in mammals), Ase1 (in yeast), and MAP65 (in plants) are evolutionarily conserved non-motor microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) that selectively crosslink microtubules in an antiparallel orientation [21]. They serve as the primary architectural element that "marks" regions of antiparallel overlap, forming compliant crosslinks that define bundle organization.

Structural and biophysical studies reveal that PRC1 functions as a homodimer, utilizing a combination of a structured spectrin-fold domain and an unstructured Lys/Arg-rich basic domain to bind microtubules [21]. This dual-domain structure is key to its function. The linker between the two microtubule-binding domains exhibits flexibility on single microtubules but forms well-defined, rigid crossbridges when engaging two antiparallel filaments [21]. This unique property allows PRC1 to selectively stabilize antiparallel configurations while allowing for dynamic reorganization.

The Influence of Microtubule Length on Assembly Geometry

The length of the microtubule building blocks is a critical determinant of the final assembly's shape. Long microtubules tend to form extended bundles. In contrast, short microtubules are essential for the formation of tapered, spindle-shaped tactoids [20]. The use of GMPCPP, a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog, to nucleate and stabilize short filaments is a common strategy to obtain a high density of short microtubules that serve as the mesogens for tactoid self-assembly [20].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Geometrical Parameters on Microtubule Organization by PRC1 and Kif4A

| Geometrical Parameter | Experimental System | Impact on Microtubule Organization | Quantitative Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Overlap Length | PRC1 & Kinesin-4 (Kif4A) [22] | Regulates sliding velocity | Sliding velocity scales with initial microtubule-overlap length |

| Microtubule Length | PRC1 & Kinesin-4 (Kif4A) [22] | Defines size of final stable overlap | Width of the final overlap scales with microtubule lengths |

| Motor Density | Kinesin-14 (Ncd) [23] | Determines rotational pitch of sliding microtubules | Helical pitch varies with motor density (0.5 to 3 µm observed) |

| Motor Extension | Kinesin-14 (Ncd) [23] | Defines spatial separation of cross-linked filaments | In situ motor extension measured at ~20 nm |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Formation of Microtubule Tactoids

This protocol enables the self-assembly of spindle-shaped microtubule tactoids using the antiparallel crosslinker MAP65 and a crowding agent [20] [1].

Reagents and Materials:

- Tubulin: Purified, lyophilized, unlabeled and fluorescently-labeled.

- Crosslinker: MAP65, Ase1, or PRC1.

- Crowding Agent: Polyethylene Glycol (PEG).

- Stabilizing Nucleotide: GMPCPP for nucleating short, stable microtubules.

- Imaging Chamber Components: Silanized coverslips.

Procedure:

- Coverslip Silanization: Clean coverslips are irradiated with UV-Ozone to remove background fluorescence. They are then treated with dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) in a fume hood to create a hydrophobic surface, which facilitates subsequent coating with a block copolymer to form a polymer brush [20].

- Tubulin Preparation: Resuspend lyophilized tubulin in cold PEM-80 buffer (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8). Mix unlabeled and fluorescently-labeled tubulin to a final concentration suitable for visualization (e.g., 5 mg/mL) [20].

- Short Microtubule Preparation: Polymerize tubulin in the presence of GMPCPP to generate a population of short, stable microtubules. The specific incubation conditions (time, temperature) will determine the average filament length.

- Tactoid Assembly: In the assembled imaging chamber, combine the short microtubules with MAP65 and PEG. The final solution should contain:

- Microtubules (concentration tuned for assembly, e.g., 2-5 µM tubulin dimer)

- MAP65/PRC1 (e.g., 50-100 nM)

- PEG (e.g., 1-2% w/v as a crowding agent)

- Incubation and Imaging: Allow the mixture to incubate for 15-60 minutes at room temperature to facilitate self-assembly. Image the resulting tactoids using fluorescence microscopy. Characterize shape and constituent mobility using techniques like Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) [20] [1].

Protocol 2: Simultaneous Visualization of Crosslinked and Single Microtubule Dynamics

This TIRF microscopy assay allows for the direct comparison of dynamic properties between PRC1-crosslinked microtubule bundles and single microtubules under identical conditions [24].

Reagents and Materials:

- Assay Buffer (BRB80): 80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8.

- Oxygen Scavenging System: Glucose oxidase, catalase, and glucose to reduce photodamage.

- Blocking Agents: Kappa-casein or Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Microtubule Seeds: Biotinylated, GMPCPP-stabilized microtubule fragments for surface immobilization.

Procedure:

- Imaging Chamber Preparation: Create a flow chamber using a silanized coverslip and a glass slide. Introduce NeutrAvidin (0.2 mg/mL) to coat the surface, followed by a blocking step with kappa-casein (0.5 mg/mL) [24].

- Surface Immobilization of Microtubule Seeds: Flow in biotinylated microtubule seeds and allow them to immobilize on the NeutrAvidin-coated surface.

- Generation of Crosslinked Bundles: Introduce PRC1 (e.g., 0.2 nM) to form crosslinks between immobilized seeds and free microtubules, creating bundled architectures alongside single microtubules [22] [24].

- Initiation of Dynamics: Flow in the final assay mixture containing:

- Soluble tubulin (e.g., 10-15 µM)

- GTP (1 mM)

- ATP (1 mM, if motors are used)

- Oxygen scavenging system

- Relevant MAPs or motor proteins of interest

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Use multi-wavelength TIRF microscopy to simultaneously record the dynamics (growth, shrinkage, catastrophe, rescue) of single and crosslinked microtubules over time. Kymograph analysis is used to extract dynamic parameters [24].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps for this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Microtubule Crosslinking and Shape Determination Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Antiparallel Crosslinkers | Selectively binds and bundles antiparallel microtubules, defining array architecture. | PRC1 (human), Ase1 (yeast), MAP65 (plant); homo-dimeric [21]. |

| Kinesin Motor Proteins | Drives relative sliding and generates mechanical forces within crosslinked arrays. | Kinesin-4 (Kif4A): plus-end-directed, regulates sliding and dynamics [22]. Kinesin-14 (Ncd): minus-end-directed, induces helical sliding [23]. |

| Microtubule Stabilizers | Generates short, stable microtubules as building blocks for defined assemblies. | GMPCPP: nucleates short, stable filaments resistant to catastrophe [20]. Taxol: stabilizes microtubule lattice, suppresses dynamics. |

| Crowding Agents | Mimics intracellular crowded environment, promotes condensation and phase separation. | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): induces depletion forces that bundle filaments [20]. Methylcellulose: increases solution viscosity, used in motility assays. |

| Actin-Microtubule Crosslinkers | Links actin and microtubule cytoskeletons, enabling crosstalk and force transmission. | Tau: MAP that bundles F-actin and crosslinks it to microtubules [25]. TipAct: engineered crosslinker for actin transport by microtubule ends [26]. |

| Pexidartinib | Pexidartinib, CAS:1447274-99-8, MF:C20H15ClF3N5, MW:417.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GSK481 | GSK481, MF:C21H19N3O4, MW:377.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Concepts and Inter-System Crosstalk

The principles of shape determination extend beyond single-network systems. A powerful example of cytoskeletal crosstalk is the transport of actin filaments by growing microtubule ends, mediated by passive crosslinkers like the engineered TipAct protein [26]. This transport arises from a force balance: a forward condensation force is generated by the preferential binding of crosslinkers to the chemically distinct microtubule tip region, which attempts to maximize the overlap with the actin filament. This is antagonized by a backward friction force caused by crosslinkers binding to the microtubule lattice [26]. This mechanism, distinct from motor-driven transport, illustrates how passive crosslinkers can enable one cytoskeletal system to actively remodel another.

The following diagram illustrates this force balance mechanism:

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative analysis is key to understanding the mechanisms of shape determination. The following parameters should be measured and analyzed:

- For Tactoid Assays:

- Shape Characterization: Length, width, and aspect ratio of assembled tactoids.

- Material Properties: FRAP to measure mobility and turnover of constituents (tubulin, crosslinkers) within the assembly [20].

- For Sliding and Dynamics Assays:

- Sliding Velocity: Tracked from kymographs or time-lapse sequences [22] [24].

- Helical Parameters: For 3D assays, measure helical pitch and diameter of sliding trajectories [23].

- Dynamic Instability Parameters: For dynamic microtubules, quantify growth/shrinkage rates, and catastrophe/rescue frequencies from single and crosslinked populations [24].

The integration of short, stable microtubules with specific antiparallel crosslinking proteins provides a powerful minimal system for understanding the physical principles of cytoskeletal shape determination. The protocols and data outlined here offer a reproducible path for in vitro reconstitution and quantitative analysis, forming a critical foundation for research in cell biophysics, cytoskeletal engineering, and drug discovery targeting cellular architecture.

A Detailed Protocol for Creating and Observing Microtubule Tactoids

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required for research on tubulin and microtubule tactoid self-assembly.

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Tubulin (from brain tissue) | The fundamental protein subunit (dimer) that polymerizes to form microtubules. Purified from fresh porcine or bovine brain via polymerization/depolymerization cycles. [27] [28] |

| MAP65/Ase1/PRC1 | An antiparallel microtubule crosslinking protein, essential for bundling microtubules into spindle-like tactoid structures. A key minimal component for in vitro reconstitution. [2] [15] |

| GMPCPP (Guanosine-5'-[(α,β)-methyleno]triphosphate) | A slowly-hydrolyzable GTP analog. Used to nucleate and stabilize microtubules, preventing dynamic instability and enabling the creation of short, stable microtubules necessary for tactoid formation. [29] [2] |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | A crowding agent that creates depletion interactions, increasing the local concentration of microtubules and promoting their condensation and self-assembly into larger structures like tactoids. [2] |

| GTP (Guanosine Triphosphate) | The natural nucleotide required for tubulin polymerization. It is incorporated into the growing microtubule end and subsequently hydrolyzed, regulating dynamics. [27] [29] |

| Phosphocellulose (PC) Resin | A cation-exchange chromatography medium used for the final purification step of tubulin, separating it from microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). [27] [28] |

| Pipes Buffer | A common buffering agent (pH 6.6-6.9) used in tubulin and microtubule protocols to maintain a stable chemical environment. [27] |

Tubulin Preparation from Brain Tissue

This protocol describes the large-scale preparation of tubulin from fresh pig or cow brains, adapted from established methods. [27] [28]

Materials and Equipment

- Biological Material: 3-5 fresh pig brains or a larger quantity (e.g., 10) of fresh cow brains.

- Buffers:

- PM Buffer: 100 mM Pipes (pH 6.9), 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSOâ‚„, 2 mM DTT. [27]

- PM-4M Buffer: PM Buffer with 4 M Glycerol. [27]

- PM-8M Buffer: PM Buffer with 8 M Glycerol. [27]

- PB (Pipes/Polymerization Buffer): 0.1 M K-Pipes (pH 6.8), 0.5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM ATP. [28]

- Nucleotides: GTP and ATP. [27] [28]

- Key Equipment: Waring blender, Dounce homogenizer, high-speed centrifuge (e.g., Sorvall with SS-34 rotor), ultracentrifuge (e.g., Beckman with Ti70 rotor), phosphocellulose (PC) column. [27] [28]

Protocol Steps

- Homogenization: Remove meninges and blood vessels from fresh brains in a cold room. Homogenize the tissue in a pre-cooled Waring blender with PM-4M buffer. [27]

- Clarification: Centrifuge the homogenate at low speed (e.g., 9,500 rpm in an SS-34 rotor) to remove debris. Then, centrifuge the resulting supernatant at high speed (e.g., 96,000 × g) to obtain a clear lysate. [27]

- First Polymerization Cycle: Add GTP to the lysate to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Incubate the mixture at 34-37°C for 45-60 minutes to polymerize microtubules. Pellet the polymerized microtubules by warm centrifugation (e.g., 30,000 rpm at 27°C). [27] [28]

- First Depolymerization: Resuspend the pellet in a small volume of cold PM buffer and homogenize using a Dounce homogenizer. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes to depolymerize microtubules. Clarify by cold, high-speed centrifugation to remove aggregates. The supernatant contains tubulin. [27]

- Second Polymerization/Depolymerization Cycle: Repeat steps 3 and 4 to increase the purity of the tubulin. The volume of buffer used for resuspension can be based on the volume from the first cycle (e.g., 0.25 × V1). [27]

- Phosphocellulose Chromatography: Apply the twice-cycled tubulin supernatant to a pre-equilibrated PC column. Elute with PM buffer. The flow-through contains pure tubulin, while microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) bind to the column. [27]

- Storage: Pool the pure tubulin fractions, add an equal volume of PM-8M buffer, divide into aliquots, freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C. [27]

Self-Assembly of Microtubule Tactoids

This protocol describes the formation of spindle-shaped microtubule assemblies (tactoids) using stabilized microtubules, the crosslinker MAP65, and PEG. [2]

Materials

- Proteins: Purified tubulin, MAP65.

- Nucleotide: GMPCPP.

- Crowding Agent: Polyethylene Glycol (PEG).

- Imaging Supplies: Glass coverslips.

- Specialized Chemicals: Dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) for silanization. [2]

Protocol Steps

- Coverslip Silanization (for sample chambers):

- Clean coverslips with water and ethanol, then treat with UV-Ozone (UVO) or plasma to remove organic residue. [2]

- In a fume hood, immerse the coverslips in a 2% solution of dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) in a suitable container for 5 minutes. Caution: DDS is highly toxic. [2]

- Rinse the coverslips thoroughly with 100% ethanol and then water. Air-dry completely in the fume hood. This creates a hydrophobic surface for subsequent polymer brush coating. [2]

- Formation of GMPCPP-stabilized Microtubules:

- Polymerize tubulin in the presence of GMPCPP to create short, stabilized microtubules. The specific protocol for GMPCPP microtubule growth should be followed. [2]

- Tactoid Assembly Reaction:

- Combine the stabilized, short microtubules with the antiparallel crosslinker MAP65.

- Include PEG in the reaction mixture to act as a crowding agent, which promotes self-assembly through depletion forces. [2]

- Incubate the mixture to allow for the formation of long, thin, spindle-shaped tactoids.

- Characterization:

Table 1: Key Buffers for Tubulin Preparation

| Buffer Name | Composition | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| PM Buffer [27] | 100 mM Pipes (pH 6.9), 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSOâ‚„, 2 mM DTT | General tubulin handling and depolymerization. |

| PM-4M Buffer [27] | PM Buffer + 4 M Glycerol | Homogenization buffer; glycerol aids in polymerization cycles. |

| PM-8M Buffer [27] | PM Buffer + 8 M Glycerol | Tubulin storage at -20°C. |

| PB (Pipes/Polymerization Buffer) [28] | 0.1 M K-Pipes (pH 6.8), 0.5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM ATP | Buffer used in large-scale preps for polymerization. |

Table 2: Centrifugation Parameters for Tubulin Prep

| Step | Rotor Type | Speed & Duration | Temperature | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarification [27] | Sorvall SS-34 | 9,500 rpm for 15 min | 4°C | Remove tissue debris. |

| Lysate Clearance [27] | Beckman Ti70 | 96,000 × g for 75 min | 4°C | Obtain clear supernatant for polymerization. |

| Polymer Pellet (Cycle 1) [27] | Beckman Ti70 | 96,000 × g for 60 min | 27°C | Pellet polymerized microtubules. |

| Depolymerization Clearance [27] | Beckman Ti70 | 96,000 × g for 60 min | 4°C | Remove aggregates after depolymerization. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Tubulin Protein Purification Workflow

Tactoid Self-Assembly Workflow

Nucleotide Role in Microtubule Assembly

Within the broader research on the self-assembly of microtubule tactoids, the preparation of the experimental substrate is a critical foundational step. The formation of these spindle-like liquid crystal assemblies, which serve as minimalistic models for the mitotic spindle, is highly sensitive to surface interactions [20] [7]. The self-organization of microtubules into tactoids requires a specific set of conditions, including the use of an antiparallel crosslinker like MAP65 and a crowding agent such as Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [20] [2]. The role of the flow chamber surface is to minimize undesired adsorption of these components and to prevent non-specific sticking of microtubules, which could disrupt the delicate self-organization process [20]. The protocol outlined herein describes the silanization of glass coverslips to create a hydrophobic surface, which subsequently allows for the application of a non-adsorbing polymer brush coating (e.g., Pluronic F-127) within the final flow chamber [20] [7]. This treatment is essential for achieving a reproducible environment in which microtubule tactoids can form and be observed without interference from the surface.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the key materials required for the silanization process and their specific functions in the protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials for Coverslip Silanization

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Glass Coverslips | Serves as the primary substrate for constructing the flow chamber. |

| Dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) | A highly toxic silane compound that reacts with the glass surface to create a stable hydrophobic layer [20]. This layer is crucial for the subsequent attachment of a block copolymer brush. |

| Acetone (100%) | Organic solvent used for deep cleaning the coverslip surface to remove organic residues [20]. |

| Ethanol (100%) | Used for rinsing and cleaning steps to remove water and other solvents [20]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH), 0.1 M | Aqueous base used to clean and hydroxylate the glass surface, preparing it for the silanization reaction [20]. |

| UV-Ozone (UVO) Machine or Plasma Chamber | Used for high-level cleaning and removal of any fluorescent contaminants from the glass surface prior to silanization [20]. |

Equipment

- Metal coverslip-holding racks (dedicated one for UVO/plasma and another for silanization)

- Fume hood

- Lint-free laboratory wipes

- Tweezers

- Containers for immersion steps

Experimental Protocol

NOTE: The following procedure must be performed in a fume hood while wearing appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves. Dimethyldichlorosilane is highly toxic and must be handled with utmost care [20].

Initial Coverslip Cleaning

- Rinse: Rinse the coverslips thoroughly with ddHâ‚‚O, followed by 70% ethanol, and then ddHâ‚‚O again. Dry the coverslips with lint-free laboratory wipes between each rinse. This sequence removes dust and water-soluble or organic particles from the surface [20].

- UV-Ozone/Plasma Treatment: Place the coverslips in a dedicated metal rack and transfer them to a UV-Ozone (UVO) machine. Irradiate the coverslips for 20 minutes to eliminate any background fluorescence. A plasma chamber can be used as an effective alternative to UVO [20].

- Transfer: Using tweezers, transfer the coverslips from the rack used for UVO treatment to a different, pre-cleaned metal rack designated for the silanization process. Using separate racks prevents cross-contamination and high levels of oxidation [20].

Detailed Solvent Cleaning Sequence

This series of immersion steps ensures the surface is impeccably clean and ready for chemical modification.

- Acetone Immersion: Immerse the rack with coverslips in a container with 100% acetone for 1 hour. After immersion, rinse the container 3 times with tap water and then 3 times with ddHâ‚‚O to remove all traces of acetone [20].

- Ethanol Immersion: Immerse the rack in 100% ethanol for 10 minutes. Rinse the container 3 times with tap water and then 3 times with ddHâ‚‚O [20].

- Water Rinses: Immerse the rack 3 times in ddHâ‚‚O for 5 minutes each [20].

- KOH Immersion: Immerse the rack in 0.1 M KOH (prepared by adding 50 mL of 1 M KOH to 450 mL of ddHâ‚‚O) for 15 minutes. Rinse the container 3 times with tap water and then 3 times with ddHâ‚‚O [20].

- Final Water Rinses: Immerse the rack 3 more times in ddHâ‚‚O for 5 minutes each [20].

- Drying: Air-dry the rack with the coverslips overnight in a fume hood or laminar flow hood [20].

Silanization Reaction

- Silane Application: After ensuring the coverslips and rack are completely dry, immerse them for 5 minutes in a 2% solution of dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) in a container used specifically for silane. It is critical that no moisture is introduced at this stage. [20]

- Ethanol Rinses: Immerse the rack and coverslips 2 times in a container with 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each. Rinse the container 3 times with tap water and then 3 times with ddHâ‚‚O afterward [20].

- Water Rinses: Immerse the rack and coverslips 3 times in ddHâ‚‚O for 5 minutes each [20].

- Final Drying: Air-dry the rack with the coverslips overnight in a fume hood or laminar flow hood [20].

- Storage: Using tweezers, transfer the silanized coverslips into coverslip boxes. These treated coverslips remain usable for 1-2 months. Coverslips that are stored longer may lose their coating effectiveness and should be discarded [20].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential stages of the flow chamber preparation process, from initial cleaning to the final readiness for the tactoid assay.

Quantitative Data & Specifications

Table 2: Critical Parameters and Timing for the Silanization Protocol

| Process Step | Key Parameter | Specification / Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Ozone Cleaning | Duration | 20 minutes | Alternatively, use a plasma chamber. |

| Acetone Immersion | Duration & Concentration | 1 hour in 100% Acetone | Removes organic residues. |

| KOH Immersion | Concentration & Duration | 15 minutes in 0.1 M KOH | Cleans and hydroxylates the surface. |

| Silanization | Concentration & Duration | 5 minutes in 2% DDS | Critical step. Must be performed in a fume hood with dry materials. |

| Drying Steps | Duration | Overnight (x2) | Essential for complete reaction and evaporation of solvents. |

| Coated Coverslip Shelf Life | Usability Period | 1 to 2 months | Old coatings lose effectiveness and should be discarded. |

Within the broader research on the self-assembly of microtubule tactoids, the preparation of the tubulin mix and the final reaction solution constitutes a foundational and critical step. This protocol details the precise methodology for combining purified tubulin with essential nucleotides, crowding agents, and crosslinking proteins to create the conditions necessary for the spontaneous formation of spindle-shaped microtubule assemblies [2] [6]. The reproducibility of tactoid self-assembly is highly dependent on the accuracy and timing of these preparatory steps, which are designed to create a minimalistic in vitro system that mimics the liquid crystal properties of the mitotic spindle [1] [2]. The following sections provide a detailed, step-by-step guide for researchers to prepare the tubulin mix and the final reaction solution, ensuring consistent and reliable results.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the key reagents required for preparing the tubulin mix and reaction solution for microtubule tactoid assembly.

- Table 1: Essential Reagents for Tubulin Tactoid Assembly

Reagent Name Function in the Protocol Key Specifications / Notes Unlabeled Tubulin Primary structural protein for microtubule assembly; forms the bulk of the tactoid structure. Lyophilized, stored at -80°C. Resuspended in cold PEM-80 buffer [7]. Rhodamine-Labeled Tubulin Fluorescent marker for visualization of microtubules via fluorescence microscopy. Lyophilized, stored at -80°C. Typically constitutes a small fraction of the total tubulin mix [7]. PEM-80 Buffer Tubulin resuspension and reaction buffer. Provides the ionic conditions necessary for tubulin stability and polymerization. Composition: 80 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl₂, pH 6.8 [7]. GMPPCPP (Guanylyl-(α,β)-methylene-diphosphonate) Non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue used to nucleate and stabilize microtubule seeds, protecting them from depolymerization [2]. Creates stable microtubule nuclei from which dynamic microtubules can grow [2]. MAP65 (with GFP tag) Antiparallel microtubule crosslinker; essential for bundling microtubules into spindle-shaped tactoids. Plant homolog of PRC1/Ase1. GFP tag allows visualization of the crosslinker's localization [2] [7] [6]. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Crowding agent. Creates depletion forces that increase the effective tubulin concentration and promote microtubule condensation [2]. --- Pluronic F-127 Non-ionic block copolymer surfactant. Passivates the chamber surface to prevent non-specific adhesion of microtubules [7]. --- Glucose Oxidase/Catalase Oxygen-scavenging system. Reduces photodamage during fluorescence microscopy by removing reactive oxygen species [7]. --- Dithiothreitol (DTT) Reducing agent. Helps maintain protein stability and function by preventing oxidation of cysteine residues [7]. ---

Detailed Methodology

Preparation of the Tubulin Working Mix

The first critical stage involves creating a ready-to-use tubulin aliquot that combines unlabeled and fluorescently labeled tubulin.

- Thaw Reagents: Retrieve one aliquot of unlabeled tubulin (1 mg lyophilized powder) and one aliquot of rhodamine-labeled tubulin (20 µg lyophilized powder) from the -80°C freezer. Place both immediately on ice [7].

- Resuspend Tubulin:

- To the 1 mg unlabeled tubulin aliquot, add 200 µL of cold PEM-80 buffer.

- To the 20 µg rhodamine-labeled tubulin aliquot, add 4 µL of cold PEM-80 buffer.

- Keep both tubes on ice for 10 minutes to ensure the lyophilized powder is fully dissolved. Gently pipette up and down if necessary, avoiding bubble formation [7].

- Combine Tubulins: Transfer 100 µL of the resuspended unlabeled tubulin solution into the tube containing the 4 µL of rhodamine-labeled tubulin [7].

- Mix and Aliquot:

- Mix the combined solutions by pipetting slowly up and down 6-7 times.

- Distribute the final tubulin mix into seven new tubes, with 15 µL in each.

- Immediately snap-freeze the aliquots in liquid nitrogen and return them to the -80°C freezer for future use. This step ensures tubulin stability and allows for reproducible experiments over time [7].

Preparation of the Final Reaction Solution

The assembly of the final reaction must be performed efficiently and with reagents kept on ice to preserve tubulin functionality. The entire process from mixing to loading into the flow chamber should be completed within 10-12 minutes [7].

- Prepare Flow Chamber: Prior to preparing the reaction mix, coat a silanized flow chamber with 20 µL of a 5% solution of Pluronic F-127 in PEM-80. Incubate the chamber in a humidified environment (e.g., a Petri dish with a wet lint-free wipe) for at least 5-7 minutes to allow for surface passivation [7].

- Combine Reaction Components: In a sterile tube kept on ice, combine the following reagents in the order listed. Mix by pipetting 5-6 times after addition [7].

- PEM-80 buffer

- GMPPCPP

- Pluronic F-127

- Dithiothreitol (DTT)

- Glucose

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

- The prepared Tubulin Mix (from step 3.1)

- MAP65 (with GFP-MAP65 for visualization)

- Add Oxygen Scavengers: Introduce 1 µL of a pre-mixed glucose oxidase and catalase solution into the reaction tube. Mix the entire solution thoroughly by pipetting 7-8 times [7].

- Load the Chamber:

- Remove the Pluronic F-127 solution from the flow chamber by capillary action, using a lint-free wipe placed at the opposite end of the chamber.

- Immediately add the prepared tubulin-MAP65 reaction mix to the chamber entrance to draw it in via capillary action [7].

- Seal and Incubate: Once the sample has filled the chamber, seal both ends with five-minute epoxy glue. Transfer the chamber to a 37°C incubator for 30 minutes to allow for microtubule nucleation and tactoid growth [7].

The preparation of reagents is characterized by specific volumetric and concentration parameters, which are summarized below for quick reference.

- Table 2: Quantitative Data for Tubulin and Reaction Preparation

Parameter Value Relevance / Context Unlabeled Tubulin Mass 1 mg Mass in one primary aliquot for resuspension [7]. Rhodamine-Tubulin Mass 20 µg Mass in one primary aliquot for resuspension; creates a labeled fraction for imaging [7]. Final Tubulin Mix Aliquot Volume 15 µL Volume of single-use working aliquots stored at -80°C [7]. Chamber Coating Volume 20 µL Volume of 5% Pluronic F-127 used to passivate the flow chamber [7]. Chamber Coating Time 5-7 minutes Minimum incubation time for surface passivation [7]. Reaction Preparation Timeframe 10-12 minutes Maximum recommended time from mixing to loading; critical for tubulin activity [7]. Tactoid Assembly Incubation 30 minutes Time required at 37°C for complete tactoid formation [7]. Incubation Temperature 37°C Temperature for microtubule nucleation and tactoid growth [7].

This application note details the procedure for assembling and incubating microtubule tactoids, which are spindle-shaped, liquid-crystal-like assemblies of microtubules. This protocol is a critical step in reconstituting self-organized spindle-like structures in vitro using a minimal system comprising short, stabilized microtubules, the antiparallel microtubule crosslinker MAP65, and the crowding agent polyethylene glycol (PEG) [2] [1]. The formation of these tactoids provides a valuable model for studying the physical principles of biological self-organization, relevant to processes such as mitotic spindle formation and the behavior of mesoscale liquid crystals [2] [30].

Reagent Preparation

Tubulin Stock Solution

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Unlabeled Tubulin | 1 mg lyophilized [7] | Primary structural component for microtubule assembly. |

| Rhodamine-Labeled Tubulin | 20 µg lyophilized [7] | Fluorescent marker for microtubule visualization. |

| PEM-80 Buffer | Cold [7] | Buffer for reconstituting and storing tubulin. |

Procedure:

- Obtain an aliquot of unlabeled tubulin (1 mg lyophilized) and an aliquot of rhodamine-labeled tubulin (20 µg lyophilized) from a -80 °C freezer and keep them on ice [7].

- Add 200 µL of cold PEM-80 to the unlabeled tubulin vial. Add 4 µL of cold PEM-80 to the rhodamine-labeled tubulin vial [7].

- Keep both tubes on ice for 10 minutes to dissolve the lyophilized material completely [7].

- Combine 100 µL of the resuspended unlabeled tubulin with the entire 4 µL of rhodamine-labeled tubulin. Mix by pipetting slowly 6-7 times [7].

- Distribute the tubulin mix into aliquots of 15 µL in new tubes. Flash-freeze the aliquots in liquid nitrogen and store them at -80 °C for future use [7].

MAP65 Working Solution

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| MAP65 | Plant-derived, recombinant [2] | Anti-parallel microtubule crosslinking protein, essential for tactoid shape. |

| GFP-MAP65 | Optional [7] | Fluorescently tagged version for visualizing crosslinker localization. |

Assembly Mix Components

| Component | Typical Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PEM-80 Buffer | To volume [7] | Reaction buffer. |

| GMPCPP | As required [7] | Non-hydrolyzable GTP analog; nucleates and stabilizes short microtubules. |

| Pluronic F-127 | As required [7] | Non-ionic block copolymer surfactant; prevents surface adhesion. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | As required [7] | Reducing agent; maintains protein integrity. |

| Glucose | As required [7] | Substrate for oxygen-scavenging system. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | As required [2] [7] | Macromolecular crowder; induces depletion forces that promote tactoid condensation. |

| Glucose Oxidase/Catalase Mix | 1 µL pre-mixed [7] | Oxygen-scavenging system; reduces photodamage during fluorescence imaging. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the tactoid assembly and incubation protocol.

Detailed Protocol

Flow Chamber Assembly

Principle: A sealed, passivated flow chamber is required to contain the reaction mixture and prevent non-specific adhesion of microtubules to glass surfaces, which would inhibit tactoid formation [2] [7].

Procedure:

- Silanization of Coverslips (Perform in a fume hood):

- Rinse coverslips sequentially with ddHâ‚‚O, 70% ethanol, and ddHâ‚‚O, drying with lint-free wipes between rinses [2].

- Place coverslips in a metal rack and irradiate with UV-Ozone (UVO) for 20 minutes (or use plasma treatment) to remove background fluorescence [2].

- Immerse the rack with coverslips in 2% dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS) in a dedicated container for 5 minutes. Caution: DDS is highly toxic. [2]

- Rinse the rack and coverslips twice in 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each [2].

- Air-dry the rack and coverslips overnight in a fume hood or laminar flow hood [2].

- Chamber Construction:

- Clean a glass slide with ddHâ‚‚O and ethanol, then dry it [7].

- Create two thin strips from double-sided tape (40-50 mm long) and place them on the slide 5-8 mm apart to form a flow path [7].

- Place a silanized coverslip on top of the tape strips to form the chamber [7].

- Press gently with the back of a pen on the tape region to seal. A good seal will turn the tape from translucent to clear [7].

- Trim excess tape with a razor blade, leaving about 1 mm at the chamber entrance [7].

Tactoid Assembly and Incubation

Principle: The core assembly mix combines stabilized microtubule seeds, free tubulin, the MAP65 crosslinker, and a crowding agent. Under controlled incubation, this leads to the self-organization of microtubules into tactoids [2] [7].

Procedure:

- Thaw all necessary reagents (tubulin aliquot, MAP65, etc.) on ice [7].

- Chamber Coating: Pipette 20 µL of 5% Pluronic F-127 surfactant in PEM-80 into the flow chamber. Place the chamber in a humidified Petri dish for at least 5-7 minutes [7].

- Prepare Assembly Mix: In a sterile tube on ice, combine the following by pipetting 5-6 times:

- PEM-80 buffer

- GMPCPP

- Pluronic F-127

- Dithiothreitol (DTT)

- Glucose

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

- Thawed tubulin mix

- MAP65 (including a small amount of GFP-MAP65 for visualization) [7].

- Add 1 µL of the pre-mixed glucose oxidase/catalase solution to the assembly mix. Mix by pipetting 7-8 times [7].

- Critical Note: The entire process of preparing the assembly mix should be completed within 10-12 minutes to maintain tubulin integrity [7].