The Eukaryotic Cytoskeleton: Structure, Dynamics, and Emerging Therapeutic Targets

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, exploring its fundamental structure and dynamic functions essential for cell integrity, division, and motility.

The Eukaryotic Cytoskeleton: Structure, Dynamics, and Emerging Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, exploring its fundamental structure and dynamic functions essential for cell integrity, division, and motility. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into advanced methodologies for cytoskeletal analysis, including AI-driven techniques, and examines the critical interplay between cytoskeletal dynamics and disease mechanisms such as cancer progression and DNA damage response. The review further discusses the optimization of cytoskeleton-targeting agents, compares therapeutic strategies, and validates emerging targets, offering a synthesized perspective on the cytoskeleton's pivotal role in cellular biology and its implications for developing novel clinical interventions.

Architecture and Core Mechanics of the Eukaryotic Cytoskeleton

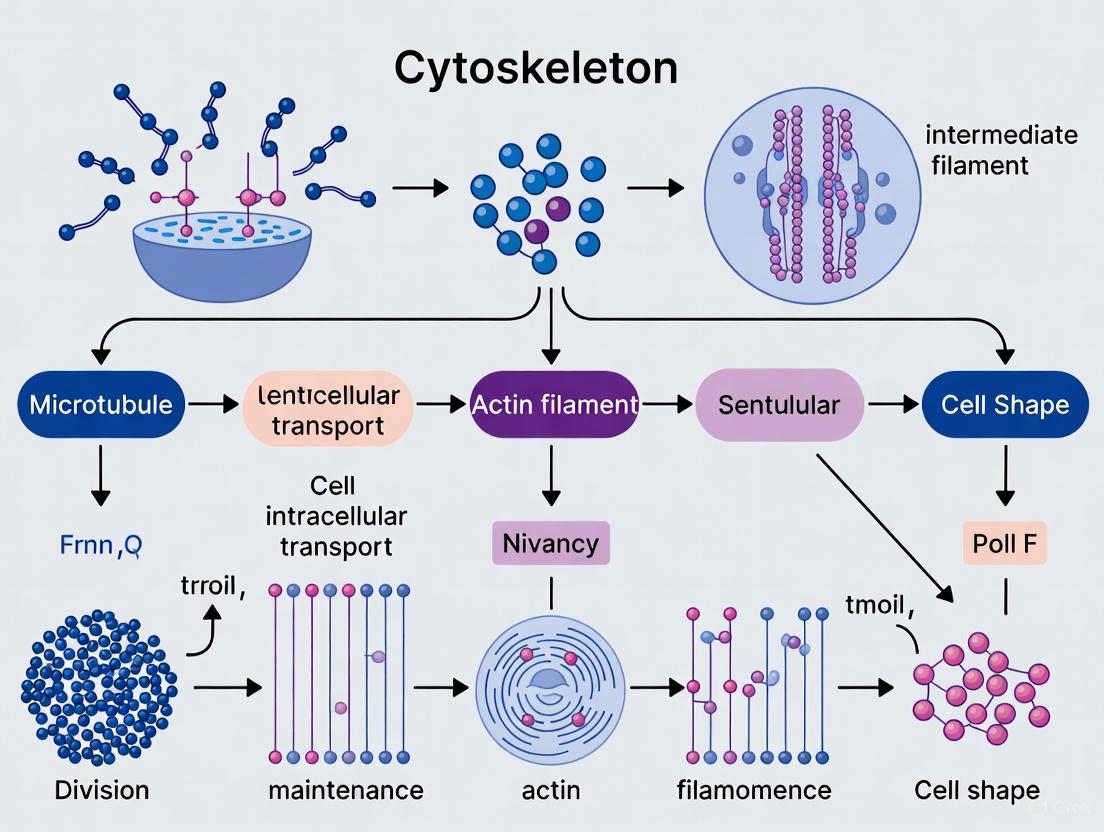

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells, extending from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane [1]. This tripartite system, composed of microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, serves as a fundamental structural determinant that is indispensable for cellular life. Its functions transcend mere architectural support, encompassing critical roles in maintaining cell shape, enabling motility, facilitating intracellular transport, and ensuring proper cell division [2] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinct properties and synergistic interactions of these three filament systems is crucial, not only for deciphering basic cell biology but also for identifying novel therapeutic targets in diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases [3] [1]. This whitepaper provides a detailed technical guide to the core components of the cytoskeletal network, framing their characteristics within the context of modern biomedical research.

Core Components of the Cytoskeleton

Microfilaments (Actin Filaments)

Structure and Composition: Microfilaments, with a diameter of approximately 7 nm, are the narrowest components of the cytoskeleton [2]. They are composed of the globular protein actin (G-actin) that polymerizes to form a double-helical strand known as filamentous actin (F-actin) [2] [4]. These filaments are polarized, featuring a fast-growing barbed end (+) * and a slow-growing *pointed end (-) [5] [4]. Their dynamics are powered by ATP and tightly regulated by a suite of actin-binding proteins (ABPs) such as profilin (promotes assembly), formin (promotes elongation), and cofilin (promotes disassembly) [5].

Primary Functions:

- Cell Motility and Contraction: Working with motor proteins like myosin, actin filaments facilitate muscle contraction and cellular crawling, as exemplified by white blood cells chasing pathogens [2] [1].

- Maintenance of Cell Shape: They form a cortical network beneath the plasma membrane that defines cell morphology [2].

- Cytokinesis: The contractile ring that pinches a dividing cell into two is composed of actin and myosin [1] [4].

- Cytoplasmic Streaming: In plant cells, actin networks facilitate the flow of cytosol to distribute nutrients and organelles [2] [4].

- Mechanotransduction: Actin stress fibers, connected to the extracellular matrix via focal adhesions, allow cells to sense and respond to mechanical cues from their environment [5].

Microtubules

Structure and Composition: Microtubules are the largest cytoskeletal components, with a diameter of about 25 nm [2]. They are hollow cylinders whose walls are composed of protofilaments—linear chains of alternating α-tubulin and β-tubulin heterodimers [2] [4]. Typically, 13 protofilaments associate to form a single microtubule. They are nucleated from a microtubule-organizing center (MTOC), such as the centrosome in animal cells [2]. Like microfilaments, microtubules are polarized, with a dynamic plus end (+) * that grows rapidly and a more stable *minus end (-) that is often anchored to the MTOC [4].

Primary Functions:

- Intracellular Transport: Microtubules serve as tracks for motor proteins (kinesins and dyneins) that transport vesicles, organelles, and protein complexes [3].

- Cell Division: They form the mitotic spindle, which is responsible for the accurate segregation of chromosomes during mitosis [2] [3].

- Cell Shape and Compression Resistance: Their rigidity helps the cell resist compressive forces [2].

- Formation of Cilia and Flagella: Microtubules are the core structural elements of these motile and sensory organelles, arranged in the characteristic "9+2" axoneme [2].

Intermediate Filaments

Structure and Composition: Intermediate filaments have an intermediate diameter of 8-12 nm, from which they derive their name [2] [1]. Unlike the other two filament types, they are non-polar and are composed of a diverse family of fibrous proteins, including keratin (in epithelial cells), vimentin (in mesenchymal cells), neurofilaments (in neurons), and nuclear lamins [2] [1]. Their assembly involves the formation of a coiled-coil dimer, which then associates into tetramers and ultimately into the final, ropelike filament [1].

Primary Functions:

- Mechanical Strength: Their primary role is purely structural—to bear tension and provide mechanical strength to the cell and tissues [2] [1].

- Anchorage of Organelles: They anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place within the cytoplasm [2].

- Tissue Integrity: Through desmosomes and other junctions, intermediate filaments create a continuous network that provides tensile strength across entire tissues [1].

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Cytoskeletal Components

| Feature | Microfilaments | Microtubules | Intermediate Filaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~7 nm [2] | ~25 nm [2] | ~10 nm [2] [1] |

| Protein Subunit | Actin (G-actin) [2] | α- and β-Tubulin heterodimer [2] | Various (e.g., Keratin, Vimentin, Lamin) [2] [1] |

| Structure | Two intertwined actin strands [4] | Hollow cylinder of 13 protofilaments [4] | Ropelike, fibrous tetramers [1] |

| Polarity | Polar (Barbed+/Pointed-) [5] | Polar (Plus+/Minus-) [4] | Non-polar [1] |

| Nucleotide | ATP [5] | GTP [4] | None |

| Dynamic Instability | Yes (Treadmilling) | Yes (Dynamic instability) [4] | No (Stable) [2] |

| Primary Function | Cell motility, contraction, cytokinesis [2] | Intracellular transport, mitosis, cell shape [2] | Mechanical strength, organelle anchorage [2] |

Experimental Methodologies for Cytoskeletal Analysis

Studying the cytoskeleton requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines biochemical, imaging, and pharmacological techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experimental procedures used in the field.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Microscopy for Filament Visualization

This protocol is foundational for visualizing the spatial organization of all three cytoskeletal networks in fixed cells.

Materials:

- Cultured cells grown on glass coverslips

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Blocking solution (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS)

- Primary antibodies (e.g., anti-α-tubulin for microtubules, anti-vimentin for intermediate filaments)

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies

- Actin stain (e.g., phalloidin conjugated to a fluorophore) [6]

- Mounting medium with DAPI (for DNA counterstain)

- Fluorescence or confocal microscope

Procedure:

- Cell Fixation: Aspirate the culture medium from cells on a coverslip and rinse gently with warm PBS. Fix the cells by incubating in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Remove the fixative and wash the cells 3 times with PBS. Incubate with permeabilization buffer (0.1% Triton X-100) for 10 minutes to allow antibodies access to the cytoskeleton.

- Blocking: Wash the coverslip with PBS and apply blocking solution (e.g., 1% BSA) for 30-60 minutes to reduce nonspecific antibody binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply the primary antibody diluted in blocking solution to the coverslip. Incubate in a humidified chamber for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Secondary Antibody and Phalloidin Incubation: Wash the coverslip 3 times with PBS to remove unbound primary antibody. Apply a mixture of fluorescent secondary antibody and fluorescent phalloidin (to label F-actin) diluted in blocking solution. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Mounting and Imaging: Perform final washes with PBS and then distilled water. Mount the coverslip onto a glass slide using an anti-fade mounting medium. Seal the edges with nail polish. Image using a fluorescence or confocal microscope with appropriate filter sets.

In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay

This biochemical assay is used to quantify the polymerization dynamics of microtubules and is critical for screening drugs that target tubulin [3].

Materials:

- Purified tubulin protein (>99% pure)

- PEM buffer (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl₂, pH 6.9)

- GTP (Guanosine-5'-triphosphate)

- Spectrophotometer or fluorometer with temperature control

- Pre-warmed microcuvettes

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: On ice, prepare a tubulin solution (e.g., 3 mg/mL) in PEM buffer containing 1 mM GTP. Keep the solution on ice to prevent premature polymerization.

- Baseline Measurement: Transfer the tubulin solution to a pre-warmed cuvette in the spectrophotometer set to 37°C. Immediately start monitoring the turbidity (absorbance at 350 nm) or fluorescence if using a tubulin-coupled fluorophore.

- Data Collection: Continue measuring the absorbance for 60-90 minutes. The absorbance will initially be low, then increase as microtubules polymerize and scatter light, eventually plateauing as the reaction reaches equilibrium.

- Data Analysis: Plot absorbance vs. time. Key parameters to analyze include the nucleation lag time, the maximum growth rate (slope), and the final polymer mass. To test a drug's effect, include it in the initial reaction mix; inhibitors will suppress the turbidity increase, while stabilizers may enhance it or lower the critical concentration for assembly [3].

Drug-Based Perturbation of the Actin Cytoskeleton

This functional assay uses specific pharmacological agents to disrupt actin dynamics and observe the phenotypic consequences.

Materials:

- Cultured cells

- Actin-targeting drugs (e.g., Latrunculin B, Cytochalasin D, Jasplakinolide) [5] [6]

- Cell culture medium

- Live-cell imaging setup (optional)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells onto culture dishes or coverslips and allow them to adhere and spread normally.

- Drug Application: Prepare a working concentration of the chosen drug in culture medium.

- Incubation and Observation: Replace the culture medium with the drug-containing medium. Incubate cells for a predetermined time (e.g., 30 minutes to 2 hours).

- Analysis: Fix and stain the cells with phalloidin (as in Protocol 3.1) to visualize changes in actin architecture. Alternatively, use live-cell imaging to monitor dynamic processes like cell edge retraction or the cessation of cytoplasmic streaming in real-time. Expected outcomes include the disappearance of stress fibers (with Latrunculin B/Cytochalasin D) or excessive actin aggregation (with Jasplakinolide).

Visualization of Cytoskeletal Dynamics and Signaling

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows central to cytoskeletal research.

Actin Mechanotransduction Pathway

This diagram visualizes the pathway through which extracellular mechanical signals are transduced into transcriptional changes via the actin cytoskeleton and YAP/TAZ signaling, a key pathway in cell fate determination [5].

Workflow for Screening Cytoskeletal-Targeting Compounds

This flowchart outlines an integrated strategy for the discovery and validation of novel cytoskeletal-targeting drugs, as demonstrated in the identification of Gatorbulin-1 [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A curated selection of pharmacological agents is indispensable for probing cytoskeletal structure and function. The table below details key reagents used to manipulate and study the cytoskeleton in experimental settings.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Cytoskeletal Manipulation

| Reagent Name | Target | Effect on Cytoskeleton | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latrunculin B [6] | Actin | Sequesters G-actin; prevents polymerization & enhances depolymerization | Disrupting actin-based structures to study motility, endocytosis, and mechanotransduction. |

| Cytochalasin D [6] | Actin | Caps F-actin barbed ends; prevents polymerization. | Inhibiting actin filament elongation; studying cytokinesis and cell shape. |

| Jasplakinolide [6] | Actin | Stabilizes F-actin; promotes polymerization. | Hyper-stabilizing actin filaments to study consequences of reduced dynamics. |

| Phalloidin [6] | Actin | Stabilizes F-actin; prevents depolymerization. | Fluorescently-labeled: Staining and visualizing F-actin in fixed cells. |

| Nocodazole [7] [6] | Microtubules | Binds β-tubulin; prevents polymerization. | Depolymerizing microtubules to study mitosis, intracellular transport, and organelle positioning. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) [6] | Microtubules | Binds and stabilizes microtubules; suppresses dynamics. | Hyper-stabilizing microtubules; a common chemotherapeutic and research tool. |

| Vinblastine [7] [6] | Microtubules | Binds tubulin dimers; prevents polymerization. | Inducing mitotic arrest; studying vesicular transport. |

| Colchicine [6] | Microtubules | Binds tubulin; prevents polymerization. | Studying microtubule dynamics; treating gout (clinical use). |

| Gatorbulin-1 [3] | Microtubules | Binds a novel intradimer site; inhibits polymerization. | Example of a novel, naturally-derived compound with a unique mechanism of action. |

The eukaryotic cytoskeleton, a tripartite network of microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, represents a pinnacle of cellular engineering. Its components—each with distinct structural properties, dynamic behaviors, and molecular regulators—are not isolated systems but are functionally integrated to orchestrate complex cellular behaviors. From enabling the rapid migration of an immune cell to the faithful segregation of genetic material, the cytoskeleton is fundamental to life. Current research continues to reveal the complexity of this network, including its roles in signal transduction, nuclear functions, and cellular reprogramming [5]. For the drug development community, the cytoskeleton remains a "validated target for novel therapeutic drugs" [3]. The ongoing discovery of new binding sites and compounds, coupled with a deeper understanding of the off-target effects of cytoskeletal drugs on processes like protein folding [7], promises a new generation of more specific and effective therapeutics for cancer and other devastating diseases. The methodologies and reagents outlined in this whitepaper provide the foundational toolkit for driving these innovations forward.

Molecular Composition and Structural Properties of Each Filament System

The cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells is a dynamic, multifaceted network of protein filaments essential for cellular integrity, intracellular organization, and motility. This system is not a static scaffold but a highly regulated infrastructure composed of three principal filament classes: microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments [8]. Each system possesses a unique molecular composition and structural profile, enabling a diverse yet integrated set of mechanical and transport functions within the cell [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these distinct properties is paramount, as the cytoskeleton presents a rich target for therapeutic interventions in diseases ranging from cancer to chronic kidney disease [10]. This whitepaper provides a detailed technical guide on the core molecular and structural features of each filament system, framing this knowledge within contemporary research methodologies.

Core Filament Systems: A Comparative Analysis

The following section delineates the defining characteristics of the three cytoskeletal filaments, with quantitative data summarized for direct comparison.

Molecular and Structural Properties

Table 1: Comparative Structural Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

| Property | Microfilaments | Intermediate Filaments | Microtubules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Subunit | Actin (globular) [9] [11] | Keratin family, Vimentin, Desmin, Lamins, Neurofilaments (fibrous) [12] [13] [14] | Tubulin heterodimer (α- and β-tubulin) [9] [13] |

| Diameter | ~7 nm [11] [2] | ~10 nm [12] [13] | ~25 nm [12] [13] |

| Structure | Two intertwined strands of actin (helical) [2] | Ropelike, eight protofibrils forming a staggered array [12] [14] | Hollow cylinder of 13 linear protofilaments [9] [13] |

| Polarity | Yes (barbed and pointed ends) [12] | No [12] | Yes (plus and minus ends) [13] |

| Dynamic Instability | High (ATP-dependent) [9] [11] | Low (very stable) [9] [8] | High (GTP-dependent) [13] [11] |

| Primary Mechanical Role | Bears tension, cortical strength [9] | Bears tension, mechanical strength [11] [8] | Resists compression [9] [11] |

| Motor Proteins | Myosin [9] [15] | None known | Kinesin, Dynein [9] [15] |

Detailed System Profiles

Microfilaments (Actin Filaments): Microfilaments are composed of globular actin (G-actin) monomers that polymerize into helical filaments (F-actin) in an ATP-dependent manner [9] [13]. This polarity is critical for their function, as the barbed end elongates faster than the pointed end. They form a meshwork known as the cell cortex beneath the plasma membrane, providing mechanical support and determining cell shape [14]. Their dynamic nature allows them to rapidly assemble and disassemble, facilitating processes like cell crawling, cytokinesis, and cytoplasmic streaming [11] [2]. The motor protein myosin interacts with actin filaments to generate contractile forces in muscle and non-muscle cells [15].

Intermediate Filaments: Constructed from a diverse family of fibrous proteins, intermediate filaments are the most stable and durable component of the cytoskeleton [9] [8]. Their assembly involves the formation of a staggered, ropelike structure from coiled-coil dimers, resulting in non-polar filaments that lack known motor proteins [12]. Their primary function is mechanical integrity, as they distribute tensile stress throughout the cell and anchor organelles like the nucleus [11] [2]. Different cell types express specific intermediate filament proteins (e.g., keratins in epithelial cells, desmin in muscle, neurofilaments in neurons), making them valuable cell-type-specific markers [12] [14].

Microtubules: As the largest cytoskeletal filaments, microtubules are hollow tubes composed of α/β-tubulin heterodimers that assemble in a GTP-dependent manner [9] [11]. Their inherent polarity is fundamental to their role as tracks for intracellular transport; the plus ends typically extend toward the cell periphery, while the minus ends are anchored at the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC), or centrosome [12] [13]. Motor proteins kinesin (plus-end-directed) and dynein (minus-end-directed) transport vesicles, organelles, and other cargo along these tracks [9] [15]. Microtubules are also the fundamental components of mitotic spindles, cilia, and flagella, the latter possessing a characteristic "9+2" array of microtubule doublets [11] [2].

Experimental Analysis of Cytoskeletal Dynamics

Research into cytoskeletal function often requires assessing filament organization and dynamics in response to genetic or chemical perturbations. The following protocol, inspired by recent research, details a methodology for evaluating the role of a cytoskeleton-associated protein in podocytes, which can be adapted for other cell types.

Experimental Protocol: Investigating Cytoskeletal Protein Function via Knockdown and Imaging

This protocol outlines the steps to analyze the functional role of a cytoskeleton-associated protein (e.g., Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4, CKAP4) in maintaining cytoskeletal architecture [10].

1. Objective: To determine the effect of targeted protein knockdown on the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton in cultured human podocytes (applicable to other eukaryotic cells).

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: Human Podocytes (HPODs) or other relevant eukaryotic cell line.

- Knockdown Reagent: Specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or translation-blocking morpholino (MO) targeting the gene of interest [10].

- Control Reagent: Non-targeting siRNA or control MO.

- Transfection Reagent: Appropriate agent for delivering siRNA/MO into the cells.

- Cell Culture Media: Standard growth media for the chosen cell line.

- Hyperglycemic Stimulus: Glucose solution to prepare 60 mM glucose media for diabetic disease modeling [10].

- Fixative: 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Permeabilization Agent: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Blocking Buffer: 1-5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS.

- Primary Antibodies: Mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody, Rabbit anti-CKAP4 antibody [10].

- Actin Stain: Phalloidin conjugate (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin) for labeling F-actin.

- Secondary Antibodies: Fluorescently-labeled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies.

- Nuclear Stain: DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

- Mounting Medium: Antifade mounting medium.

- Imaging Equipment: High-resolution fluorescence or confocal microscope.

3. Methodology: 1. Cell Seeding and Transfection: Plate human podocytes in appropriate culture vessels and allow them to adhere. Transfert cells with either the targeted siRNA/MO or the control reagent using the manufacturer's protocol [10]. 2. Experimental Stimulation (Optional): For disease modeling, treat a subset of transfected cells with 60 mM glucose media for a sustained period (e.g., two weeks) to mimic a pathological hyperglycemic environment [10]. 3. Cell Fixation and Processing: After the experimental period, wash cells with PBS and fix with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, then block with 1% BSA for 1 hour. 4. Immunofluorescence Staining: Incubate cells with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-α-tubulin, anti-CKAP4) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Wash and incubate with appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies and phalloidin conjugate for 1 hour at room temperature. Include DAPI to label nuclei [10]. 5. Microscopy and Image Analysis: Mount stained cells and image using a high-resolution fluorescence or confocal microscope. Acquire z-stack images to capture the full 3D structure of the cytoskeleton. Analyze images for changes in actin cytoskeleton architecture (e.g., disruption of stress fibers) and microtubule organization (e.g., loss of oriented growth) in knockdown cells compared to controls [10].

The workflow for this experimental approach is summarized in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for cytoskeletal analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Research

| Reagent | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Tubulin Dimers (Purified) | In vitro polymerization assays to study microtubule dynamics and drug effects [9]. |

| Phalloidin Conjugates | High-affinity staining of F-actin for fluorescence microscopy; stabilizes filaments [10]. |

| siRNA / Morpholinos | Gene knockdown tools to deplete specific cytoskeletal proteins and study loss-of-function phenotypes [10]. |

| Anti-Tubulin Antibodies | Immunofluorescence and Western blotting to visualize and quantify microtubule organization and protein levels [10]. |

| Anti-Actin Antibodies | Detection of actin isoforms and total actin levels in cellular lysates or tissues. |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Microtubule-stabilizing drug used to suppress dynamic instability and probe microtubule function [13]. |

| Latrunculin A | Actin-depolymerizing agent used to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton and study its roles in cellular processes [13]. |

| 3D Bioprinted Spheroids | Advanced cell culture models that recapitulate the biomechanical and spatial cues of the tumor microenvironment for studying invasion [16]. |

Cytoskeletal Dysfunction in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of the cytoskeleton is a hallmark of numerous diseases, making it a critical area for drug development. In Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD), the loss of cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 (CKAP4) in podocytes leads to dysregulation of both microtubule and actin networks, causing foot process effacement and proteinuria [10]. This exemplifies how a defect in a single regulator can disrupt the entire cytoskeletal infrastructure.

In cancer, the concept of cytoskeletal remodeling is central to invasion and metastasis [16]. Tumor cells adapt to mechanical stress within their microenvironment by altering their cytoskeleton, enhancing their ability to squeeze through tissue barriers. This has spurred the development of migrastatic therapies, which aim to halt metastasis by targeting the cytoskeletal machinery of cell motility rather than proliferation [16]. These therapies may target motor proteins, actin polymerization, or the associated signaling pathways.

The relationships between cytoskeletal dysfunction, cellular adaptation, and therapeutic intervention are illustrated below.

Figure 2: Cytoskeletal remodeling in disease and therapy.

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, adaptive network of protein filaments that provides mechanical support, organizes intracellular contents, and generates coordinated forces essential for cellular function in eukaryotic cells. Unlike a static skeleton, this system undergoes continuous remodeling through regulated assembly and disassembly of its constituent polymers—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments [17]. These processes are fundamental to cell division, motility, intracellular transport, and shape determination. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise mechanisms governing cytoskeletal dynamics offers valuable therapeutic targets, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases where these processes are frequently dysregulated [18] [1]. This technical guide examines the core principles of cytoskeletal polymerization and the sophisticated regulatory systems that control these dynamics, providing a framework for both basic research and translational applications.

Core Polymer Systems: Structure and Assembly Dynamics

The eukaryotic cytoskeleton comprises three distinct filament systems, each with unique structural properties and dynamic behaviors. The quantitative characteristics of these systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Cytoskeletal Polymers

| Property | Actin Filaments | Microtubules | Intermediate Filaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | 7-9 nm [19] | 23-25 nm [1] [19] | 8-12 nm [1] [19] |

| Subunit | G-actin [20] | αβ-tubulin heterodimer [21] | Tissue-specific proteins (e.g., vimentin, keratin) [1] |

| Persistence Length | ~17 µm [17] (as a semi-flexible polymer) | ~5 mm [17] | Not specified in results |

| Structural Polarity | Yes (+ and - ends) [20] | Yes (+ and - ends) [21] | No (apolar) [19] |

| Nucleotide Dependence | ATP [19] | GTP [21] | None |

| Critical Concentration | ~0.1 µM for polymerization [20] | Dependent on tubulin concentration [19] | Not applicable |

| Primary Mechanical Role | Bear tension, generate protrusive forces [1] [17] | Resist compression, organize intracellular space [17] [19] | Provide mechanical stability, bear tension [1] [19] |

Actin Filaments: Force Generation and Motility

Actin exists in monomeric (G-actin) and filamentous (F-actin) states, assembling into helical polymers that are semi-flexible in nature [20]. Polymerization proceeds through a nucleation-elongation mechanism, where the formation of an actin trimer serves as the rate-limiting nucleation step, followed by rapid elongation [20] [22]. Filaments exhibit structural polarity, with a fast-growing barbed end (+) and a slow-growing pointed end (-) [20]. The (+)-end has a approximately ten times higher polymerization rate than the (-)-end [20]. ATP hydrolysis following monomer incorporation regulates filament dynamics, with ATP-actin predominating at the (+)-end and ADP-actin at the (-)-end [20]. Actin polymerization drives essential cellular processes including cell migration, phagocytosis, and cytokinesis by generating protrusive forces against cellular membranes [1] [17].

Microtubules: Architectural Scaffolds and Intracellular Highways

Microtubules are hollow cylinders composed of 13 protofilaments, each formed by αβ-tubulin heterodimers arranged in a head-to-tail fashion, creating structural polarity [21]. Microtubules exhibit dynamic instability, a stochastic switching between growth (polymerization) and shrinkage (catastrophe), powered by GTP hydrolysis [21] [17]. The GTP-bound tubulin at the growing end forms a protective "cap" that stabilizes the microtubule; hydrolysis to GDP-tubulin in the lattice promotes depolymerization if the cap is lost [21]. This dynamic behavior allows microtubules to rapidly reorganize their architecture and "search" intracellular space [17]. Microtubules originate from microtubule-organizing centers (MTOCs), with their minus ends anchored at the centrosome and plus ends extending toward the cell periphery, establishing a polarized network for intracellular transport [21] [19].

Intermediate Filaments: Mechanical Integrators

Intermediate filaments are non-polar, stable polymers that provide mechanical integrity and resistance to stress [1] [19]. Their assembly mechanism differs fundamentally from actin and microtubules, involving the formation of tetramers that associate laterally into protofilaments and ultimately mature filaments [19]. Unlike the other cytoskeletal systems, intermediate filament assembly is not nucleotide-dependent [19]. Their composition is tissue-specific (e.g., keratins in epithelial cells, vimentin in mesenchymal cells, neurofilaments in neurons), allowing specialized mechanical properties tailored to different cell types [1]. The primary role of intermediate filaments is to provide structural continuity throughout the cell, distributing mechanical stress and stabilizing cellular architecture [1] [19].

Regulatory Systems: Controlling Polymer Dynamics

Cytoskeletal dynamics are precisely controlled through a sophisticated network of regulatory proteins and signaling pathways that respond to intracellular and extracellular cues.

Actin-Binding Proteins and Their Functions

Actin dynamics are regulated by a diverse array of actin-binding proteins that control nucleation, elongation, capping, severing, and cross-linking. The functions of key regulatory proteins are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Regulatory Proteins for Actin Dynamics

| Regulatory Protein | Primary Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Profilin | Polymerization regulation [20] | Binds G-actin, inhibits spontaneous nucleation, promotes ATP-ADP exchange [20] |

| Arp2/3 Complex | Nucleation [20] | Binds existing filaments to nucleate branched networks [20] |

| Formins (mDia1/2) | Nucleation & elongation [20] | Processively caps barbed ends, promoting rapid elongation with profilin [20] |

| Cofilin/ADF | Severing & depolymerization [18] [20] | Binds and severs ADP-rich filaments, promoting disassembly [18] [20] |

| Capping Protein | Elongation control [20] | Binds barbed ends to prevent further polymerization [20] |

| α-actinin/Fascin | Cross-linking [20] | Bundles filaments into higher-order structures [20] |

| Myosin II | Contractility [20] | Motor protein that generates force on actin filaments [20] |

The regulation of actin networks extends beyond individual proteins to include complex signaling pathways. The Rho GTPase family (Rho, Rac, Cdc42) serves as a master regulator of actin organization, controlling the formation of specific actin-based structures in response to extracellular signals [18] [20]. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways regulating actin dynamics:

Microtubule-Associated Proteins and Regulation

Microtubule dynamics are controlled by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) that either stabilize or destabilize filaments, and by motor proteins that transport cargo and organize the network [21] [19]. Stabilizing MAPs, such as tau and MAP2, bind along microtubule lattices, promoting assembly and reducing catastrophe frequency [18] [21]. These proteins often contain projection domains that space microtubules in bundles, particularly evident in neuronal axons [21] [19]. Conversely, destabilizing MAPs like katanin sever microtubules, while Op18/stathmin promotes depolymerization by sequestering tubulin dimers [19]. Motor proteins of the kinesin and dynein families transport vesicles, organelles, and proteins along microtubule tracks, with most kinesins moving toward the plus end and dyneins toward the minus end [21] [19]. The coordinated activity of these regulatory elements enables the microtubule cytoskeleton to establish and maintain polarized cellular organization.

Integrated Regulatory Mechanisms

Beyond filament-specific regulators, broader mechanisms control cytoskeletal dynamics across all three systems:

Allosteric Regulation: Many cytoskeletal regulators function through allosteric mechanisms, where binding of a small molecule at one site alters protein conformation and activity at a distant site [23]. Feedback inhibition in metabolic pathways represents a classic example of this regulatory paradigm [23].

Protein Phosphorylation: Reversible phosphorylation serves as a universal switch controlling cytoskeletal protein activity [23]. Kinases and phosphatases regulate everything from myosin contractility to MAP binding affinity, allowing rapid integration of signaling cues [23] [20].

Mechanical Forces: The cytoskeleton functions as a mechanosensitive system, where applied physical forces can directly influence assembly and organization [17]. This mechanoresponsive capability allows cells to adapt their architecture to environmental stiffness and mechanical stresses.

The integration of these regulatory mechanisms enables the cytoskeleton to function as a coordinated system that responds appropriately to diverse cellular needs.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies and Reagents

Studying cytoskeletal dynamics requires specialized methodologies that capture both structural organization and temporal dynamics. This section outlines key experimental protocols and essential research reagents for investigating polymerization and regulatory mechanisms.

Kinetic Analysis of Actin Polymerization

The classic protocol for analyzing actin polymerization kinetics involves monitoring the increase in light absorbance or fluorescence that accompanies the G-actin to F-actin transition [22]. The following workflow details the essential steps:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cytoskeletal Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Cytoskeletal Proteins | G-actin [22], Tubulin heterodimers [17] | In vitro reconstitution of polymerization dynamics; fundamental building blocks for assembly studies |

| Nucleotide Analogs | Non-hydrolyzable ATP/GTP analogs, Mant-labeled nucleotides | Probe nucleotide dependence of polymerization; visualize real-time kinetics |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Latrunculin (actin depolymerizer) [18], Colchicine (microtubule depolymerizer), Taxol (microtubule stabilizer) [18] | Specific perturbation of cytoskeletal dynamics; therapeutic candidate screening |

| Fluorescent Probes | Phalloidin (F-actin stain) [19], Immunofluorescence antibodies for MAPs [19] | Structural visualization of cytoskeletal networks; localization of regulatory proteins |

| Regulatory Proteins | Profilin [20], Cofilin [18] [20], Tau protein [18] [21], Arp2/3 complex [20] | Mechanistic studies of regulation; reconstitution of complex dynamics |

| Live-Cell Imaging Systems | TIRF microscopy [17], FRAP, Super-resolution microscopy [18] | Real-time visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics in living cells |

Advanced Methodologies for Cytoskeletal Research

Contemporary cytoskeleton research employs increasingly sophisticated approaches:

In Vitro Reconstitution: Combining purified components (e.g., actin, Arp2/3, capping proteins) to reconstruct complex cytoskeletal structures, enabling definitive testing of molecular mechanisms [17]. Remarkably, only three proteins are required to reconstitute active cargo transport on growing microtubule ends [17].

Single-Molecule Imaging: Using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to visualize the dynamics of individual filaments and their associated proteins in real time [17].

Mechanical Perturbation: Applying precisely controlled forces to cells or reconstituted networks using optical tweezers, atomic force microscopy, or substrate stretching to investigate mechanotransduction [17].

These methodologies, combined with the research reagents detailed in Table 3, provide powerful tools for dissecting the complex regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics.

Pathophysiological Correlations and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of cytoskeletal dynamics contributes significantly to human disease pathogenesis, offering potential targets for therapeutic intervention:

Cancer Progression: Malignant cells exhibit altered actin dynamics that facilitate invasion and metastasis [18] [20]. Overexpression of actin-binding proteins like fascin and cortactin correlates with poor prognosis [18]. Microtubule-targeting agents (e.g., taxanes, vinca alkaloids) represent mainstay cancer therapeutics that exploit the heightened dependence of rapidly dividing cells on dynamic microtubules [18].

Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer's disease involves tau hyperphosphorylation, which reduces its microtubule-stabilizing function and contributes to neuronal dysfunction [18] [1]. Mutations in genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins are implicated in Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [1].

Cardiovascular Disease: Abnormal actin dynamics in vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to increased vascular tone in hypertension and atherosclerosis [18]. Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors have emerged as potential therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases through their effects on the actin cytoskeleton [18].

The cytoskeleton's central role in these pathological processes highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting cytoskeletal dynamics, with several existing clinical agents and many more in development.

The dynamic assembly and disassembly of cytoskeletal polymers, governed by complex regulatory networks, represents a fundamental biological process with broad implications for cellular function and dysfunction. The principles outlined in this technical guide—from the basic thermodynamics of polymerization to the sophisticated control by associated proteins and signaling pathways—provide a foundation for understanding how cells establish shape, generate movement, and organize internal contents. For researchers and drug development professionals, continued elucidation of these mechanisms offers exciting opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative conditions, and other diseases characterized by cytoskeletal dysregulation. The integrated view presented here emphasizes that the cytoskeleton functions not as a collection of individual components, but as a coherent, adaptive system that responds to both chemical and mechanical cues to direct cellular behavior.

Mechanical Roles in Cell Shape, Support, and Resistance to Deformation

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, hierarchical network of protein filaments that provides the fundamental mechanical framework of eukaryotic cells, enabling them to resist deformation, maintain structural integrity, and generate coordinated forces for shape change and movement [17] [1]. Far from being a static scaffold, it is an adaptive structure whose component polymers and regulatory proteins are in constant flux, allowing the cell to respond to both internal and external physical forces [17]. This mechanical role is critical for fundamental cellular processes, including division, migration, and the uptake of extracellular material, and its dysfunction is implicated in a range of diseases, from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders [24] [1]. This whitepaper details the distinct and collaborative mechanical functions of the three primary cytoskeletal networks—microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules—and provides a technical overview of the experimental methodologies used to quantify their mechanical properties and organization.

Mechanical Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

The cytoskeleton's overall mechanical behavior emerges from the distinct biophysical characteristics of its three constituent filament systems and the architecture of their assembled networks [17].

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanical Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

| Filament Type | Diameter | Primary Mechanical Role | Stiffness (Persistence Length) | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin Filaments (Microfilaments) | ~7 nm [25] [26] | Resist tension, generate contractile forces [1] | Lower stiffness; highly flexible [17] | Double helix of F-actin [26]; form branched networks, bundles, and stress fibers [17] |

| Intermediate Filaments | ~10 nm [1] [26] | Resist tension, provide mechanical toughness [1] | Flexible, but great tensile strength [27] | Ropelike, apolar structure of coiled-coil dimers [27] [1]; tissue-specific expression (e.g., keratin, vimentin) [1] |

| Microtubules | ~25 nm [24] [1] | Resist compression, provide structural tracks [1] | High stiffness (~5 mm persistence length) [17] | Hollow tubes of α/β-tubulin heterodimers [17] [26]; exhibit dynamic instability [17] |

Table 2: Network-Level Mechanical Behavior of Cytoskeletal Structures

| Structure/Network | Composition & Organization | Mechanical Function | Regulatory Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Actin Mesh | Dense, crosslinked meshwork of actin filaments beneath the plasma membrane [25] | Determines cell surface mechanics, resists deformation, and facilitates membrane protrusions [25] | Filamins, actinin, myosin for crosslinking and contractility [25] |

| Actomyosin Stress Fibers | Contractile bundles of actin filaments with non-muscle myosin II [25] [5] | Generate contractile force, transmit tension to substrates via focal adhesions, and enable mechanosensing [25] [5] | α-actinin (crosslinker), myosin II (motor), Rho/ROCK signaling [5] |

| Microtubule Array | Radial array of stiff microtubules nucleated from the centrosome [17] | Provides compressive resistance, defines intracellular organization, and serves as a track for motor-based transport [17] [1] | Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), severing proteins, +TIPs [17] |

| Perinuclear Actin Cap | Thick actomyosin bundles spanning the apical nuclear surface [5] | Transmits mechanical forces from the ECM to the nucleus, influencing nuclear shape and YAP/TAZ signaling [5] | LINC complex, focal adhesions [5] |

Experimental Methodologies for Quantifying Cytoskeletal Mechanics

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Viscoelasticity Measurements

AFM is a cornerstone technique for directly probing the mechanical properties of cells and their internal structures. In a typical experiment, a cell is indented with a calibrated AFM tip, and the force-displacement relationship is recorded. This data is used to derive key viscoelastic parameters, such as elastic (Young's) modulus and viscosity [28].

Detailed Protocol: Decoupling Viscoelastic Parameters of Subcellular Compartments [28]

- Cell Culture and Preparation: Seed cells onto sterile, compliant culture dishes suitable for AFM.

- AFM Calibration: Calibrate the AFM cantilever's spring constant using thermal tuning or a reference method.

- Force Mapping: Perform a grid of force-indentation measurements across the surface of the cell. To target the nucleus, indent the cell's apical center; for peripheral cytoskeleton, indent the cell edge.

- Data Fitting: Fit the resulting force-distance curves to a mechanical model (e.g., Hertzian model for elastic properties, or a standard linear solid model for viscoelasticity).

- Parameter Extraction: Extract the elastic modulus (E) and viscosity (η) for the membrane, cytoskeleton, and nucleus by analyzing the loading and relaxation phases of the indentation.

- Strain Recovery Analysis: Apply a sustained deformation and monitor the time-dependent recovery of the nuclear and cellular shape after force removal to quantify plasticity and elastic recovery [28].

Quantitative Image Analysis of Cytoskeletal Organization

Fluorescence microscopy of stained or live-cell cytoskeletal components provides rich data on organization, which can be quantified using specialized software tools to infer mechanical states.

Detailed Protocol: Quantifying Actin Stress Fiber Organization with Stress Fiber Extractor (SFEX) [25]

- Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Fix and stain cells with fluorescent phalloidin to label F-actin.

- Acquire high-resolution confocal or super-resolution images.

- Image Pre-processing:

- Enhance linear cytoskeletal structures in the raw image to facilitate binarization.

- Fiber Segmentation and Reconstruction:

- Generate a skeletonized image containing linear stress fiber fragments.

- Reconstruct full traces of stress fibers by iteratively searching for and connecting fragment pairs.

- Parameter Quantification:

- From the reconstructed fibers, automatically extract quantitative metrics, including fiber width (correlates with contractility), length, orientation, and abundance [25].

Detailed Protocol: Segmenting Focal Adhesions and Ventral Stress Fibers with SFALab [25]

- Generate Cell Mask: Create a mask from a cytoplasmic stain to define the cell area for analysis.

- Segment Focal Adhesions (FAs): Use shape-fitting algorithms on images stained for FA proteins (e.g., paxillin) to identify FA structures. Quantify morphological features like area and aspect ratio.

- Identify Ventral Stress Fibers: Enhance the original actin channel and combine it with the segmented FA image. Perform curve fitting between FA pairs to identify connecting ventral stress fibers.

- Quantification: Report metrics such as the number of ventral stress fibers per cell and per focal adhesion, which relate to the cell's contractile engagement with its substrate [25].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for analyzing cytoskeleton mechanics, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytoskeletal Mechanics Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phalloidin (Fluorescent conjugates) | High-affinity stain for F-actin [25] | Fixed-cell imaging of actin filaments and structures (e.g., stress fibers, cortex) [25] |

| Rho/ROCK Pathway Inhibitors (e.g., Y-27632) | Inhibits ROCK kinase, reducing actomyosin contractility [5] | Probing the role of cellular tension in shape, motility, and mechanotransduction [5] |

| Actin Polymerization Inhibitors (e.g., Latrunculin A, Cytochalasin D) | Disrupts F-actin dynamics (prevents polymerization or severs filaments) [5] | Dissecting the mechanical role of actin networks in cell shape and support [5] |

| Microtubule-Targeting Agents (e.g., Taxol/Paclitaxel, Nocodazole) | Stabilizes (Taxol) or depolymerizes (Nocodazole) microtubules [1] | Investigating the role of microtubules in compressive support and intracellular organization [17] [1] |

| Tubulin Antibodies | Labels α- and β-tubulin | Immunofluorescence staining of microtubule networks and organizing centers |

| Live-Cell Actin Probes (e.g., LifeAct, F-tractin) | Peptides or protein domains binding F-actin without disrupting dynamics [25] | Real-time visualization of actin cytoskeleton remodeling in living cells [25] |

Integrated Mechanical Signaling and Cellular Memory

The cytoskeleton is a key mediator of mechanotransduction, translating physical forces into biochemical signals. A central pathway involves the Rho/ROCK cascade, which is activated by external mechanical cues like substrate stiffness. ROCK then promotes the formation of contractile actomyosin stress fibers, which transmit tension to the nucleus via the LINC complex. This force transmission can alter nuclear shape and chromatin organization, influencing the activity of mechanosensitive transcription factors like YAP/TAZ, which shuttle into the nucleus to regulate genes controlling cell fate, proliferation, and survival [5]. Furthermore, recent work suggests that long-lived cytoskeletal structures may function as an epigenetic "memory," integrating past mechanical interactions to influence future cellular behavior and fate decisions [17] [5]. This underscores the profound role of the cytoskeleton not only as a mechanical scaffold but as a dynamic and adaptive regulator of cellular identity.

Spatial Organization of Cellular Contents and Intracellular Compartmentalization

The spatial organization of cellular contents and intracellular compartmentalization represents a fundamental principle of eukaryotic cell biology, directly influencing cellular function, signaling efficiency, and phenotypic behavior. This organization extends beyond mere physical arrangement to encompass dynamic, self-organizing systems that enable sophisticated information processing and response mechanisms within the cell [29] [30]. The cytoskeleton, comprising microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, provides the structural framework that establishes and maintains this organization, serving as both scaffold and dynamic regulator of intracellular architecture [8] [27].

Within this context, spatial organization is not static but emerges from complex interactions between molecular components. As Bastiaens et al. note, "Biological structures that generate function can arise from fluctuations and local interactions of proteins by self-organization" [29]. This dynamic organization enables cells to perform specialized functions, respond to environmental cues, and maintain homeostasis. Recent advances in imaging technologies and computational analysis have revealed that this organization is remarkably robust, maintaining core relationships between cellular structures despite significant cell-to-cell variation in shape and size [31].

The implications of spatial organization extend to numerous biomedical applications, particularly in drug development, where understanding the spatial context of drug targets can inform therapeutic strategies. Disruptions in spatial organization are linked to various disease states, highlighting the importance of comprehending these principles for developing targeted interventions.

Quantitative Imaging of Cellular Organization

Large-Scale Imaging Approaches

Cutting-edge research in cellular organization has been revolutionized by high-content imaging approaches that enable quantitative analysis of multiple cellular structures simultaneously. The integrated intracellular organization study generated the WTC-11 hiPSC Single-Cell Image Dataset v1, containing more than 200,000 live cells in 3D, spanning 25 key cellular structures [31]. This unprecedented scale has enabled researchers to move beyond qualitative descriptions to quantitative, statistical analyses of cellular organization.

The imaging methodology employed standardized pipelines using spinning-disk confocal microscopy with fluorescently tagged proteins representing specific organelles and cellular structures. To accurately delineate cellular boundaries in tightly packed epithelial-like hiPS cells, researchers applied deep-learning-based segmentation algorithms, achieving highly accurate 3D cell and nuclear segmentation across 18,100 fields of view [31]. This approach allowed for the precise assignment of cellular structures to individual cells, minimizing misassignment to neighboring cells.

Computational Framework for Spatial Analysis

To quantitatively describe cellular organization, researchers developed a sophisticated computational framework based on two complementary coordinate systems:

- Cell and Nuclear Shape Space: Using spherical harmonic expansion (SHE) to parameterize 3D cell and nuclear shapes, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) to create a dimensionality-reduced shape space. The first eight principal components represented approximately 70% of the total variance in cell and nuclear shape [31].

- Intracellular Coordinate System: Specifying the spatial location of every cellular structure within individual cells, normalized to the cell shape space.

This combined approach enabled the development of statistical measurements that distinguish among different types of organizational changes: (1) changes in average location of individual structures, (2) changes in location variability, and (3) changes in pairwise interactions among structures [31].

Experimental Workflow for Quantitative Imaging

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for analyzing cellular spatial organization:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for quantitative analysis of cellular spatial organization, showing the integration of imaging, segmentation, and computational analysis steps.

Key Findings from Quantitative Analysis

Application of this framework to large cell populations revealed several fundamental principles of cellular organization:

- Robustness in Interphase Cells: The integrated intracellular organization of interphase cells remained robust despite wide variation in cell shape within the population [31].

- Polarization at Colony Edges: Cells at colony edges exhibited polarization of certain structures while maintaining their functional "wiring" or interactions with other structures [31].

- Mitotic Reorganization: Early mitotic reorganization involved both changes in structure locations and their wiring, representing a fundamental shift in organizational principles [31].

Table 1: Quantitative Descriptors of Cellular Spatial Organization

| Spatial Descriptor | Measurement Approach | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Location | Normalized coordinates relative to cell and nuclear boundaries | Identifies polarization and intracellular positioning patterns |

| Location Variability | Coefficient of variation across cell populations | Measures organizational robustness or plasticity |

| Structure Interactions | Pairwise correlation of spatial distributions | Reveals functional relationships and organizational modules |

| Shape Dependence | Correlation with principal components of shape space | Determines how organization adapts to cell morphology |

Spatial Organization of Biochemical Information Processing

Spatial Designs in Biochemical Pathways

The spatial organization of intracellular components is not merely structural but fundamentally influences biochemical information processing. Cells employ various spatial "designs" – specific patterns of localization and non-localization of enzymes and substrates – that significantly impact pathway behavior [30]. These designs include compartmentalization within organelles, localization to specific membrane domains, and formation of biomolecular condensates.

The effect of spatial organization is particularly evident in basic building blocks of signaling pathways, such as covalent modification cycles (CMCs) and two-component systems (TCSs). In these systems, spatial organization can alter fundamental information processing characteristics including ultrasensitivity, threshold behavior, concentration robustness, and bistability [30]. For example, the spatial segregation of kinases and phosphatases can create signaling gradients that guide cellular responses.

Mechanisms of Spatial Regulation

Spatial organization of biochemical pathways is regulated through multiple mechanisms:

- Scaffolding Proteins: Proteins that physically assemble signaling components into functional complexes, enhancing reaction efficiency and specificity.

- Lipid Rafts and Membrane Domains: Specialized membrane microdomains that concentrate specific receptors and signaling molecules.

- Cytoskeletal Transport: Active transport of signaling components along cytoskeletal elements, particularly microtubules and actin filaments [8] [27].

- Reaction-Diffusion Mechanisms: Generation of spatial patterns through the interplay of chemical reactions and molecular diffusion [29].

The cytoskeleton plays a central role in many of these mechanisms, serving as both a structural scaffold and an active transport network. Microtubules and actin filaments provide tracks for motor proteins that move signaling complexes to specific cellular locations, enabling precise spatial control of signaling events [8].

Spatial Regulation of Bifunctional Enzymes

A particularly insightful example of spatial regulation occurs with bifunctional enzymes, which can perform both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation activities. The spatial organization of these enzymes significantly influences their functional output:

"In the model system Caulobacter crescentus, the dynamic localization of proteins at cell poles and the spatial distribution of signalling proteins play an important role during its asymmetric development. Furthermore, the choreographed temporal and spatial control of multiple bifunctional enzyme modules (enzymes, substrates) is at the heart of cell-cycle regulation and the transition between different phases" [30].

This spatial control allows cells to generate distinct signaling outputs from the same biochemical components simply by altering their spatial arrangement, providing a powerful mechanism for regulating complex processes like cell cycle progression and cellular differentiation.

Table 2: Effects of Spatial Organization on Biochemical Pathway Properties

| Pathway Property | Effect of Spatial Organization | Biological Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasensitivity | Enhanced through co-localization | Sharper transition between pathway states |

| Threshold Behavior | Modified by compartmentalization | Altered sensitivity to input signals |

| Concentration Robustness | Disrupted or enhanced by localization | Changes in output stability to concentration variations |

| Bistability | Created or eliminated by spatial coupling | Generation of stable alternative states |

| Signal Propagation | Guided by spatial gradients | Directional information flow within cells |

Cytoskeletal Architecture and Intracellular Organization

Structural Components of the Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton provides the primary structural framework for spatial organization in eukaryotic cells, consisting of three major filament systems with distinct mechanical properties and organizational capabilities:

- Microfilaments (Actin Filaments): The thinnest cytoskeletal components (3-5 nm diameter), composed of actin monomers polymerized into helical filaments [27]. They occur as meshworks or parallel bundles that determine cell shape, facilitate adhesion, and enable cell motility through continuous assembly and disassembly.

- Microtubules: The largest cytoskeletal elements (15-20 nm diameter), hollow tubes composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that assemble into protofilaments [27]. They radiate from the centrosome in animal cells, forming an intracellular transport network and the mitotic spindle during cell division.

- Intermediate Filaments: The most durable cytoskeletal components (8-10 nm diameter), comprising a diverse family of proteins including keratins, vimentin, and lamins [8] [27]. They provide mechanical strength, anchor the nucleus, and withstand cellular tension.

Cytoskeletal Functions in Spatial Organization

The cytoskeleton performs multiple essential functions in cellular spatial organization:

- Structural Support and Shape Determination: The cytoskeleton provides mechanical support, particularly important in animal cells lacking cell walls [27]. It establishes and maintains cell shape through a balance of tensile forces from microfilaments, compressive resistance from microtubules, and mechanical stability from intermediate filaments.

- Intracellular Transport: Microtubules and actin filaments serve as tracks for motor proteins (kinesins, dyneins, and myosins) that transport vesicles, organelles, and macromolecular complexes throughout the cell [27]. This directed transport enables precise positioning of cellular components.

- Organelle Positioning and Anchoring: The cytoskeleton positions and anchors organelles, often through connections with intermediate filaments [8]. For example, the nucleus is positioned within the cell by a network of intermediate filaments that connect it to the plasma membrane.

- Cell Motility: Coordinated assembly and disassembly of actin filaments, often with microtubule participation, enables cell crawling, amoeboid movement, and extension of cellular protrusions [8] [27].

- Cell Division: The cytoskeleton undergoes dramatic reorganization during cell division, forming the mitotic spindle (composed of microtubules) that segregates chromosomes and the contractile ring (composed of actin filaments) that enables cytokinesis [8] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the structural relationships and functional interactions between cytoskeletal components:

Figure 2: Cytoskeletal components and their primary functions in cellular spatial organization, showing how different filament types specialize in distinct organizational tasks.

Dynamic Properties of the Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a highly dynamic structure, constantly remodeling in response to intracellular and extracellular signals. Microfilaments and microtubules undergo rapid assembly and disassembly, a property known as dynamic instability, which allows for rapid reorganization of cellular architecture [27]. This dynamic behavior enables cells to change shape, migrate, and respond to environmental cues.

The dynamic nature of the cytoskeleton is particularly evident during cell division, when the interphase cytoskeleton disassembles and reforms as the mitotic spindle, and then reorganizes again during cytokinesis to form the contractile ring that separates the daughter cells [8]. These dramatic reorganizations demonstrate the plasticity of cytoskeletal structures and their central role in coordinating cellular spatial organization throughout the cell cycle.

Research Toolkit: Methodologies and Reagents

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Studying spatial organization and intracellular compartmentalization requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following table summarizes key research tools used in this field:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Cellular Spatial Organization

| Reagent/Tool | Composition/Type | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenously Tagged Cell Lines | hiPSC with GFP/RFP-tagged proteins | Live-cell imaging of specific organelles [31] | Precise localization of cellular structures |

| Cytoskeletal Inhibitors | Small molecules (e.g., nocodazole, latrunculin) | Perturbation studies of cytoskeletal function [8] | Dissecting cytoskeletal contributions to organization |

| Fluorescent Biosensors | Genetically encoded tension/activity sensors | Monitoring mechanical forces and signaling activity [29] | Real-time observation of spatial dynamics |

| Photoactivatable Proteins | PA-GFP, Dronpa, and other photoswitchable FPs | Protein tracking and mobility measurements [29] | Analyzing molecular diffusion and dynamics |

| Deep Learning Segmentation Tools | Convolutional neural networks | Automated 3D cell and structure segmentation [31] | High-throughput quantitative morphology analysis |

| Spherical Harmonic Parameterization | Mathematical modeling approach | Quantitative shape analysis and normalization [31] | Standardizing shape comparisons across cells |

Advanced Imaging Methodologies

Cutting-edge research in spatial organization relies heavily on advanced imaging technologies that enable high-resolution, multi-dimensional data collection:

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP): Measures protein mobility and dynamics within specific cellular compartments [29].

- Single Quantum Dot Tracking: Enables high-precision tracking of individual receptor molecules with nanometer-scale precision [29].

- Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM): Allows high-density mapping of single-molecule trajectories at sub-diffraction resolution [29].

- Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) Microscopy: Provides super-resolution imaging of cellular structures beyond the diffraction limit.

- Spatiotemporal Image Correlation Spectroscopy (STICS): Analyzes protein velocity maps and flow patterns within living cells [29].

These methodologies, combined with the computational framework described in Section 2.2, create a powerful pipeline for quantitative analysis of cellular spatial organization from the molecular to the cellular scale.

Experimental Considerations for Spatial Organization Studies

When designing experiments to investigate spatial organization, several critical factors must be considered:

- Cell State Context: Spatial organization varies with cell cycle stage, differentiation state, and environmental conditions. Studies should carefully control for these factors or explicitly incorporate them into experimental design [31].

- Multi-scale Analysis: Comprehensive understanding requires integrating data across spatial scales, from molecular interactions to cellular architecture.

- Dynamic Measurements: Static snapshots may miss important organizational dynamics. Live-cell imaging provides crucial temporal context for organizational changes [29] [31].

- Population Heterogeneity: Cell-to-cell variability is inherent in biological systems. Large-scale datasets and single-cell analysis approaches are essential for distinguishing consistent organizational principles from random variation [31].

The spatial organization of cellular contents and intracellular compartmentalization represents a fundamental determinant of cellular function, integrating structural, biochemical, and informational aspects of cell biology. Through the coordinated action of the cytoskeleton and sophisticated spatial regulation of biochemical pathways, cells achieve a remarkable level of organizational complexity that enables precise control of cellular processes.

Recent advances in quantitative imaging, computational analysis, and molecular tools have transformed our understanding of these principles, revealing both the remarkable robustness of core organizational features and the dynamic adaptability of cellular architecture. The development of large-scale datasets and analytical frameworks has moved the field from qualitative description to quantitative, statistical analysis of spatial relationships within cells.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these organizational principles provides critical insights into cellular function in both health and disease. Spatial organization affects drug targeting, signaling pathway modulation, and cellular responses to therapeutic interventions. As our understanding of these principles deepens, it opens new possibilities for manipulating spatial organization for therapeutic benefit, particularly in diseases characterized by disruptions in cellular architecture or organization. The continued integration of imaging, computational, and molecular approaches will undoubtedly yield further insights into the intricate spatial logic of cellular life.

Advanced Imaging, AI, and Functional Analysis in Cytoskeleton Research

Fluorescent Probes and Live-Cell Imaging for Cytoskeletal Dynamics

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filamentous proteins, is fundamental to eukaryotic cell biology, providing structural support, enabling intracellular transport, and facilitating cell division and migration [5]. Its major components—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—undergo continuous remodeling, and visualizing these dynamics in living cells is critical for understanding cellular function and for drug development, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases [32] [33]. Live-cell imaging of the cytoskeleton requires highly specific, bright, and minimally perturbing fluorescent probes. Advanced fluorogenic probes, combined with high-resolution microscopy techniques such as STED and SIM, now enable researchers to observe cytoskeletal architecture and dynamics with unprecedented clarity, revealing details like the ninefold symmetry of the centrosome and the organization of actin in neuronal axons [34]. This guide details the key probes, methodologies, and analytical frameworks for investigating cytoskeletal dynamics in live cells.

Fluorescent Probes for Cytoskeletal Imaging

A diverse toolkit of fluorescent probes has been developed to label and monitor the cytoskeleton in live cells. These include genetically encoded fluorescent proteins, small-molecule fluorogenic probes, and labeled chemical inhibitors that bind specifically to cytoskeletal components.

Table 1: Fluorescent Probes for Live-Cell Imaging of the Cytoskeleton

| Probe Name | Target | Type / Mechanism | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellLight Tubulin-GFP/RFP [35] | Microtubules | BacMam vector expressing β-tubulin fusion | Genetically encoded; consistent expression | Imaging cytokinesis & microtubule rearrangement |

| SiR-tubulin [34] | Microtubules | Far-red, fluorogenic small molecule | Minimal cytotoxicity; >100x brightness increase upon binding; suitable for STED | Long-term imaging; super-resolution microscopy |

| TubulinTracker Green [35] | Microtubules | Oregon Green 488 paclitaxel bis-acetate | Cell-permeant esterase-activated probe; binds polymerized tubulin | Staining polymerized tubulin in live cells (inhibits cell division) |

| Oregon Green 488 Paclitaxel (Flutax-2) [35] | Microtubules | Fluorescent paclitaxel derivative | Binds microtubules with high affinity (Kd ~10⁻⁷ M) at 37°C | Imaging microtubule formation & motility; HTS for microtubule assembly drugs |

| CellLight Talin-GFP/RFP [35] | Focal Adhesions / Actin | BacMam vector expressing talin fusion | Labels actin via talin C-terminal actin-binding domain | Studying integrin-mediated adhesion; labeling cytoskeletal actin |

| SiR-actin [34] | Actin Filaments | Far-red, fluorogenic small molecule | Minimal cytotoxicity; high photostability; suitable for STED | Long-term imaging; super-resolution microscopy of actin |

| BODIPY FL Vinblastine [35] | β-tubulin | Fluorescent analog of vinblastine | Inhibits proliferation by capping microtubule ends | Investigating β-tubulin & drug-transport mechanisms in MDR cells |

Experimental Protocols for Live-Cell Imaging

This section provides detailed methodologies for employing key fluorescent probes to visualize cytoskeletal dynamics, from basic labeling to advanced super-resolution applications.

Live-Cell Microtubule Labeling with SiR-tubulin

Principle: SiR-tubulin is a cell-permeant, fluorogenic probe that exhibits a significant increase in fluorescence upon binding to microtubules, allowing for long-term, high-resolution imaging with minimal background [34].

Reagents:

- SiR-tubulin (commercially available, e.g., CY-SC002 from Cytoskeleton, Inc.)

- Complete cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM with serum)

- Live cells (e.g., HeLa Kyoto, human primary dermal fibroblasts) seeded in imaging dishes

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: Prepare a 1-5 mM stock solution of SiR-tubulin in DMSO. Aliquot and store at -20°C.

- Cell Staining: Add the SiR-tubulin stock solution directly to the complete culture medium to achieve a final working concentration of 0.1 - 2 µM.

- Incubation: Incubate cells with the dye-containing medium for 60 minutes at 37°C in a standard CO₂ incubator.

- Washing (Optional): For some cell types, removing the dye-containing medium and replacing it with fresh pre-warmed medium can reduce background. However, SiR-tubulin's fluorogenic nature often makes this step unnecessary.

- Imaging: Image live cells on a confocal, SIM, or STED microscope using appropriate far-red laser lines and filters (e.g., 650 nm excitation, 670 nm emission).

Technical Notes:

Labeling Polymerized Tubulin with TubulinTracker Green

Principle: TubulinTracker Green reagent is a non-fluorescent, cell-permeant paclitaxel derivative. Intracellular esterases cleave lipophilic blocking groups, generating a charged, green-fluorescent molecule that binds specifically to polymerized tubulin [35].

Reagents:

- TubulinTracker Green reagent (T34075, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- 20% Pluronic F-127 solution in DMSO (provided in kit)

- Live cells in imaging dishes

Procedure:

- Stock Solution: Reconstitute the lyophilized TubulinTracker Green reagent with the provided 20% Pluronic F-127/DMSO solution to facilitate dispersal in aqueous media.

- Working Solution: Dilute the stock solution in pre-warmed serum-free medium or a suitable buffer to the manufacturer's recommended working concentration.

- Staining: Incubate cells with the working solution for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Washing: Carefully wash cells 2-3 times with fresh, pre-warmed buffer or medium to remove excess probe.

- Imaging: Image immediately using standard FITC/GFP filter sets.

Technical Notes:

- Critical Consideration: Because paclitaxel stabilizes microtubules, this probe will inhibit cell division and may disrupt other dynamic microtubule-dependent processes [35]. It is ideal for snapshot imaging of microtubule networks but not for long-term studies of dynamics.

Visualizing Actin Dynamics with SiR-actin

Principle: SiR-actin is a far-red, fluorogenic probe that binds to F-actin, offering high specificity and low toxicity for prolonged imaging of actin structures [34].

Reagents:

- SiR-actin (commercially available)

- Complete cell culture medium

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: Prepare a mM stock solution of SiR-actin in DMSO.

- Cell Staining: Add SiR-actin to the culture medium to a final concentration of 0.1 - 2 µM.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 120 minutes at 37°C.

- Imaging: Image live cells directly without washing using a far-red compatible microscope. For high-resolution imaging of structures like lamellipodia, 3D-SIM is recommended [34].

Genetically Encoded Labeling with BacMam Technology

Principle: CellLight reagents use BacMam 2.0 technology (baculovirus-based gene delivery) to express fluorescent protein fusions (e.g., GFP, RFP) with cytoskeletal proteins like tubulin or talin in mammalian cells [35].

Reagents:

- CellLight reagent (e.g., Tubulin-GFP, C10509; Talin-GFP, C10611)

- Appropriate cell culture medium

Procedure:

- Transduction: Add the CellLight BacMam reagent directly to the cell culture medium at the manufacturer's recommended particle-per-cell ratio.

- Expression: Incubate cells for 16-24 hours at 37°C to allow for adequate protein expression and incorporation into the cytoskeleton.

- Imaging: Image live cells using standard fluorescence filter sets. The expressed fusion proteins are fully integrated into the cellular cytoskeleton, allowing for accurate reporting of dynamics.

Quantitative Analysis of Cytoskeletal Dynamics

Quantifying the movement and turnover of cytoskeletal components is key to understanding force transmission and cellular motility. The molecular clutch model, developed from 2D studies, describes how retrograde flow of the actin cytoskeleton is coupled to the substrate via integrin adhesions to generate traction. Recent research confirms that a similar mechanism operates in 3D environments [36].