Micropatterning the Cytoskeleton: Controlling Cell Architecture for Fundamental Discovery and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how extracellular matrix (ECM) micropatterning has emerged as a transformative technology for standardizing cell shape and quantitatively analyzing cytoskeleton organization.

Micropatterning the Cytoskeleton: Controlling Cell Architecture for Fundamental Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how extracellular matrix (ECM) micropatterning has emerged as a transformative technology for standardizing cell shape and quantitatively analyzing cytoskeleton organization. We explore the foundational principles demonstrating how subcellular adhesive cues dictate actin, microtubule, and focal adhesion architecture, and detail state-of-the-art methodological approaches from maskless photopatterning to microcontact printing. The content further addresses troubleshooting for complex assays and validates the technology's application in elucidating disease mechanisms and screening drug effects, offering researchers and drug development professionals a critical resource for advancing mechanobiology and high-content analysis.

The Geometric Code: How Micropatterns Dictate Cytoskeletal Architecture and Cell Polarity

Core Principles and Cellular Applications

Micropatterning is a sophisticated technique that precisely manipulates the spatial distribution of cell adhesion proteins on various substrates across multiple scales. This precise control over adhesive regions facilitates the manipulation of architectures and physical constraints for single or multiple cells, enabling in-depth analysis of how chemical and physical properties influence cellular functionality [1]. Unlike conventional 2D cultures where cells grow randomly on homogeneous substrates without specific organization, micropatterning implements adhesive micropatterns to control the cellular microenvironment, allowing researchers to recapitulate multicellular architectures, tissue-tissue interfaces, and physicochemical microenvironments resembling in vivo conditions [2].

The fundamental advantage of micropatterning lies in its ability to control cell shape by constraining adhesion to predefined geometrical areas. When a cell adheres to a micropattern, it adapts and takes its shape according to the micropattern geometry—whether round, square, elongated, or more complex designs [2]. This spatial confinement directly influences cytoplasmic organization and cellular functions, including nucleus orientation and deformation [2]. For instance, in a round micropattern, both the cell and nucleus adopt circular conformation, while rectangular geometries force elliptical nuclear deformation and elongated rectangles cause aligned cellular and nuclear orientation [2].

The applications of micropatterning extend across numerous cellular functions, each benefiting from controlled microenvironments:

Cell Migration Studies: Micropatterning on thin tracks recapitulates in situ migration better than homogeneous surfaces. Cells confined to thin tracks display different centrosome positioning (located behind the nucleus) compared to cells on wide tracks or Petri dishes (centrosome oriented toward lamellipodia) [2]. Asymmetric micropatterns like connected triangles guide directional cell movement, while symmetric patterns result in random migration [2].

Cell Division and Polarity: Micropattern geometry directly influences cell division axis determination. Triangle and "L" shapes promote division along the hypotenuse axis, while "O" and "Y" shapes can induce multipolar mitosis, and "H" shapes maintain bipolar division [2]. Research combining adhesive micropatterns with laser ablation has demonstrated that retraction fibers actively guide spindle orientation during mitosis, not merely following pre-established polarity cues [2].

Cell Differentiation: Control of cell shape via micropatterning directly influences stem cell fate determination. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) differentiate into adipocytes or osteoblasts depending on micropattern island size and the consequent degree of cell spreading [2]. This demonstrates that physical parameters alone can transduce extrinsic stimuli into transcriptional responses determining stem cell niches fate.

Advanced Research Applications and Protocols

Investigating Nuclear Mechanotransduction

Experimental Background A 2025 study investigated how curvature-dependent interfacial heterogeneity influences nuclear mechanotransduction in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [3]. Researchers used PDMS-based stencils micropatterned with specific diameters (800μm and 1500μm) to create controlled cell colonies, examining how geometrical confinement regulates focal adhesion, cytoskeleton reorganization, and nuclear mechanosensing [3].

Protocol: PDMS Stencil Preparation and hMSC Culture Materials: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) films (100μm thick), 75% alcohol, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), specific puncher (800μm and 1500μm inner diameters), 24-well dishes, hMSCs (Lonza Walkersville Inc.), DMEM culture medium with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin [3].

Procedure:

- Microengineer 100μm PDMS films using a punching method to create 1.4cm diameter circles.

- Sterilize PDMS films by immersion in 75% alcohol for 30 minutes, followed by PBS washing.

- Perforate PDMS films using specific punchers to create through-film stencils (D-800 and D-1500).

- Sterilize punched microstencils again in 75% alcohol for 30 minutes and wash with PBS three times.

- Place PDMS microstencils into 24-well dishes.

- Prepare homogeneous hMSC suspensions at densities of 0.5×10⁵, 1.0×10⁵, and 2.0×10⁵ cells mL⁻¹.

- Add 1mL cell suspension into PDMS stencils to achieve low, middle, and high seeding densities.

- After 6 hours culture, refresh DMEM medium and culture hMSCs for additional 18 hours to form desired cell density and spatial heterogeneity.

- After 1 day, peel off PDMS stencils to expose microcolonies for analysis [3].

Analytical Methods

- Nuclear Staining: Fix cells with 4% PFA, treat with 1% Triton X-100, stain nuclei with DAPI, and image with fluorescent microscope. Calculate hMSC density in each microcolony using ImageJ, distinguishing between central and peripheral areas [3].

- Focal Adhesion Analysis: Perform immunofluorescent staining for integrin, vinculin, and talin-1 using primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled IgG secondary antibodies [3].

- Cytoskeleton Evaluation: Conduct immunofluorescent staining for actin, actinin, and myosin to detect cytoskeleton distribution, particularly at colony peripheries [3].

- Nuclear Mechanotransduction Assessment: Evaluate YAP nuclear translocation and laminA/C nuclear remodeling as indicators of force-sensing mechanotransduction [3].

CELLPAC Platform for Cell Patterning and Imaging

Experimental Background The CELLPAC platform represents an advanced micropatterning approach that combines micropatterned gold films, self-assembled monolayers of PEG, and cyclic RGD peptides to create microscale extracellular matrix-mimicking analogs with defined adhesive and non-adhesive boundaries [4]. This integration enables both high-fidelity cellular patterning and advanced optical imaging via surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS).

Protocol: CELLPAC Fabrication and Implementation Materials: 22mm square coverslips with 50nm gold, isopropyl alcohol, S1813 photoresist, CD26 developer, gold etchant, titanium etchant, acetone, sulfuric acid, PEG, cyclic RGD peptide [4].

Procedure:

- Gold Pattern Fabrication:

- Rinse gold-coated coverslips with isopropyl alcohol for 20 seconds and dry with compressed N₂.

- Plasma clean coverslips (gold side up) for 5 minutes at 150 watts.

- Coat coverslips with S1813 photoresist at 4000rpm for 1 minute.

- Bake at 115°C for 1 minute on hotplate.

- Expose to UV light with photomask placed atop coverslip.

- Develop in CD26 developer for 1 minute.

- Etch exposed gold using gold etchant for 1 minute and titanium layer with HCl-based etchant.

- Remove residual photoresist with acetone.

- Clean with piranha solution (3:1 H₂SO₄:H₂O₂) for 10 minutes [4].

Surface Functionalization:

- Create self-assembled monolayers of PEG on gold regions to resist protein adsorption.

- Functionalize specific areas with cyclic RGD peptide to promote cell adhesion [4].

Cell Patterning:

- Seed cells onto engineered platforms for applications ranging from single-cell patterning to complex multicellular arrangements.

- For migration assays, co-culture studies, or SERS imaging, maintain cells according to standard protocols [4].

Analytical Advantages The CELLPAC platform provides approximately three-fold enhancement in intrinsic biomolecular signals via surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, enabling label-free detection of proteins and lipids with high uniformity and remarkably low variation [4]. This facilitates real-time decoding of cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions without compromising cellular viability.

Affinity Capture for Cryo-Electron Tomography

Experimental Background A 2025 study demonstrated a micropatterning workflow for capturing minimally adherent cell types (human T cells and Jurkat cells) for cryo-FIB and cryo-ET [5]. This affinity capture system positions cells optimally for high-resolution imaging, revealing extracellular filamentous structures through improved workflow efficiency.

Protocol: Affinity Capture Cryo-ET Workflow Materials: EM grids, T cell specific antibody to human CD3, Jurkat cells, primary T cells, vitrification equipment, cryo-FIB instrumentation [5].

Procedure:

- Micropattern antibodies against CD3 onto EM grids to create capture islands.

- Apply cell suspension to grids, allowing affinity capture.

- Rinse grids to remove non-specifically bound cells.

- Vitrify grids using plunge-freezing methods.

- For intracellular imaging, mill cells to target thickness (175nm) using cryo-FIB.

- Acquire tomographic data through cryo-ET [5].

Technical Optimization Circular 10μm islands of micropatterned anti-CD3 were ideal for vitrification and cryo-FIB/SEM of Jurkat cells [5]. This approach consistently produced grids with sufficient well-positioned single cells (>10) for complete cryo-FIB sessions, significantly improving workflow efficiency compared to non-patterned approaches [5].

Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Micropattern Geometry on Cell Organization

| Micropattern Parameter | Cellular Response | Measurement Method | Significance/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small adhesive islands (5μm) | Unable to capture Jurkat cells | Cell counting on affinity grids | Minimum pattern size must accommodate cell dimensions [5] |

| 10μm circular islands | Ideal capture of single Jurkat cells | Cryo-FIB efficiency assessment | Optimal for vitrification and milling [5] |

| High cell seeding density | Enhanced YAP nuclear translocation | Immunofluorescence quantification | Increased nuclear mechanotransduction [3] |

| Colony periphery location | Increased laminA/C nuclear remodeling | Fluorescence intensity analysis | Enhanced force-sensing at curved interfaces [3] |

| Triangular patterns | Directional cell migration | Migration track analysis | Guided sequential movement between connected patterns [2] |

| Square/rectangular patterns | Elliptical nuclear deformation | Nuclear aspect ratio measurement | Cytoskeleton forces deform nucleus [2] |

Table 2: Analytical Enhancement Provided by Micropatterning Platforms

| Platform/Technique | Analytical Enhancement | Application Scope | Technical Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CELLPAC with SERS | ~3x enhancement in biomolecular signals | Protein/lipid detection, cell-cell interactions | Label-free molecular fingerprinting [4] |

| Affinity capture cryo-ET | Revelation of extracellular filaments (~10nm diameter) | Nanoscale imaging of non-adherent cells | Preserves native structures without fixation [5] |

| PDMS microstencils | Controlled cell colony formation | Nuclear mechanotransduction studies | Standardized geometrical confinement [3] |

| Adhesive micropatterns | Cytoskeleton organization control | Stem cell differentiation studies | Directs fate through shape control alone [2] |

Signaling Pathways in Micropatterned Cells

Cellular mechanotransduction pathway on micropatterned surfaces.

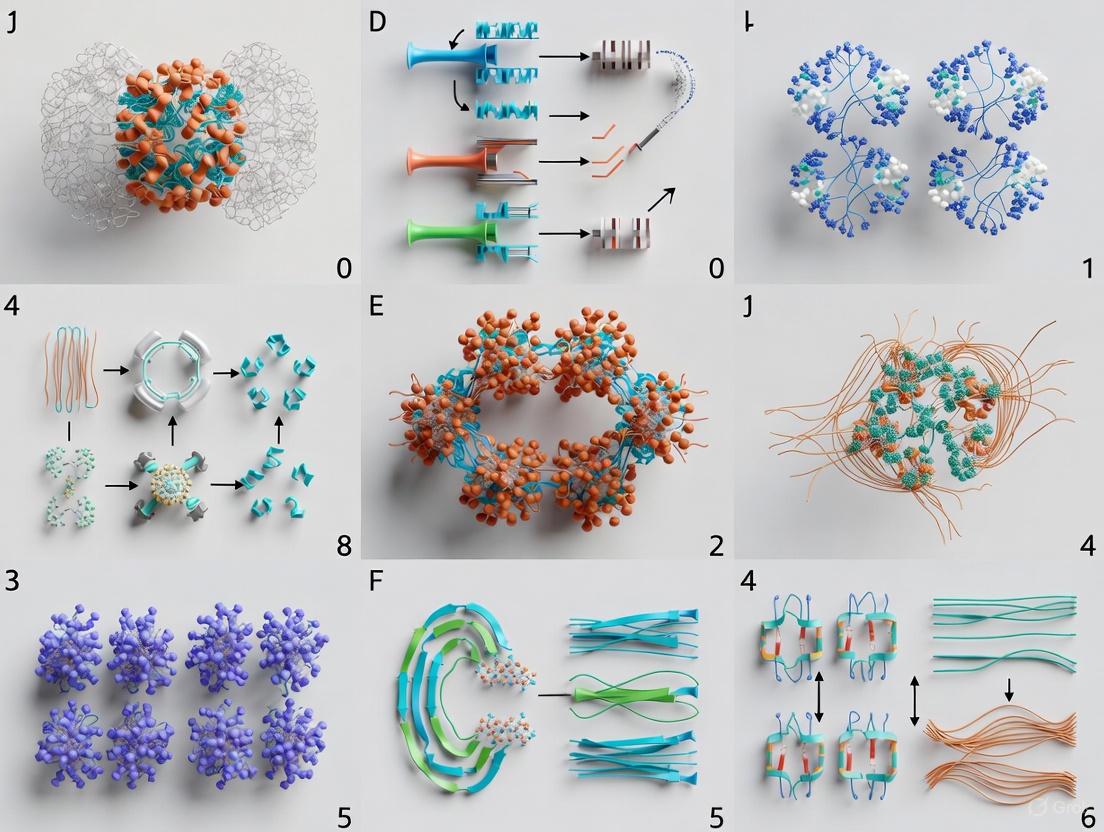

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Comprehensive micropatterning workflow for cytoskeleton studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Micropatterning

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Substrates | Base material for patterning | 22mm square coverslips with 50nm gold, glass coverslips, PDMS films [4] [3] |

| Photoresists | Create patterned features during fabrication | S1813 photoresist [4] |

| Surface Chemicals | Modify adhesion properties | PEG (non-adhesive regions), cyclic RGD peptide (adhesive regions) [4] |

| Antibodies | Affinity capture for specific cell types | Anti-CD3 for T cell capture [5] |

| Etchants | Remove specific material layers | Gold etchant, titanium etchant (HCl-based) [4] |

| Cell Types | Experimental models | hMSCs, Jurkat cells, primary T cells, HeLa cells [4] [3] [5] |

| Staining Reagents | Visualize cellular structures | DAPI (nuclei), antibodies against integrin, vinculin, talin-1 [3] |

| Imaging Substrates | Advanced microscopy | EM grids for cryo-ET [5] |

The physical microenvironment, specifically the geometry of adhesive sites, is a fundamental regulator of cell behavior. Engineered culture substrates that control extracellular matrix (ECM) geometry have proven invaluable for deconstructing how cells sense and respond to spatial cues [6] [7]. A central theme emerging from these studies is the essential role of the actin cytoskeleton, which acts as a primary sensor and transducer of geometric information [6] [7]. This application note details the core principles and methodologies for investigating how adhesive geometry is transduced into intracellular organization, providing detailed protocols for researchers in cell biology, mechanobiology, and drug development.

Key Concepts and Biological Principles

Cells integrate geometric cues from their adhesive environment through a process governed by several key principles:

- Cytoskeletal as Central Processor: The actin cytoskeleton is the primary integrator of geometric inputs. Changes in adhesive geometry directly alter actin architecture, mechanics, and organization, which in turn drives the activation of mechanotransductive signaling pathways that influence proliferation, differentiation, and migration [6] [7].

- Mechanotransduction: Physical forces generated by the cytoskeleton on adhesive sites are converted into biochemical signals. This process involves force-dependent reinforcement of adhesion complexes and cytoskeletal elements [8].

- Geometry-Dependent Phenotypes: The final cell shape, dictated by the pattern of adhesion sites, directly regulates cell fate decisions. For instance, whether a cell perimeter is convex or concave can influence stem cell lineage commitment [6].

Table 1: Techniques for Stimulating and Interrogating Cell Adhesion and Mechanics. This table summarizes key methodologies used to study cellular responses to mechanical and geometric cues, adapted from techniques often applied to cell-ECM and cell-cell adhesion studies [8].

| Technique | Force/Stress Range (Resolution) | Displacement Range (Resolution) | Primary Application in Geometric Cues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deformable Substrates | 50–1000 Pa [8] | 0–100 μm; 0%–70% strain [8] | Applying uniform strain to cell monolayers to study geometric adaptation. |

| Micropipette Aspiration | 0–700 Pa (0.1 Pa) [8] | 0–100 μm (25 nm) [8] | Probing cortical tension and mechanical properties of single cells or cell pairs. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | 0–20 nN (1 pN) [8] | 0–100 μm (1–5 nm) [8] | High-resolution mapping of cell stiffness and local mechanical properties. |

| Laser Ablation | N/A | N/A | Severing specific cytoskeletal structures (e.g., actin stress fibers) to measure prestress and viscoelastic recoil [6]. |

| Micropost Arrays | 0–100 nN (10 pN) [8] | 0–1000 nm (10 nm) [8] | Measuring traction forces generated by cells on defined, geometrically constrained posts. |

Table 2: Actin Stress Fiber (SF) Subtypes and Their Properties. Data derived from micropatterning studies combined with laser ablation reveal distinct mechanical characteristics for different SFs [6].

| Stress Fiber Subtype | Typical Location | Key Molecular Characteristics | Mechanical Properties (from Laser Ablation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventral Stress Fibers | Lower cell surface, aligned with adhesion sites | Assemble from dorsal SFs and transverse arcs or de novo; contain actin crosslinkers [6]. | High prestress; Retraction dynamics depend on assembly mechanism; presence of crosslinkers increases viscous drag [6]. |

| Transverse Arcs | Anterior of polarized cells, not directly anchored to adhesions | Myosin II-rich, dynamic [6]. | Bear significant intracellular prestress [6]. |

| Dorsal Stress Fibers | Apical cell surface, anchored to focal adhesions at ends | Transient, less contractile [6]. | Bear little to no intrinsic prestress [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Micropatterning 2D Geometries to Standardize Actin Architecture

This protocol uses microcontact printing to create defined ECM islands, controlling cell shape to investigate geometry-induced cytoskeletal organization [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps: Used to transfer ECM proteins to the substrate in a specific pattern.

- Fibronectin or other ECM Proteins: Serve as the adhesive ligand to promote integrin-mediated cell adhesion.

- Pluronic F-127 or Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): Used to passivate non-adhesive regions of the substrate and prevent non-specific cell attachment.

- Glass Coverslips or Cell Culture Dishes: The base substrate for patterning.

Methodology:

- Stamp Fabrication: Fabricate a silicon master wafer with the desired micro-patterned features (e.g., squares, rectangles, lines, bow-ties) using photolithography. Use this master to create a complementary PDMS stamp.

- "Inking": Incubate the PDMS stamp with a solution of ECM protein (e.g., 50 µg/mL fibronectin in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Printing: Gently dry the stamp and bring it into conformal contact with a plasma-treated glass coverslip for 10-30 seconds. Remove the stamp, leaving behind a protein pattern.

- Passivation: Immediately incubate the patterned coverslip with a 0.1% Pluronic F-127 solution in PBS for at least 30 minutes to block non-patterned areas.

- Cell Seeding: Seed a suspension of cells (e.g., fibroblasts, endothelial cells) at a low density onto the patterned substrate. Allow cells to adhere and spread for 4-6 hours before analysis.

- Analysis: Fix and stain cells for actin (phalloidin), focal adhesions (e.g., vinculin, paxillin), and nuclei (DAPI) for fluorescence microscopy.

Protocol: Interrogating Stress Fiber Mechanics via Laser Ablation

This protocol, used in conjunction with micropatterning, measures the viscoelastic properties of individual actin stress fibers [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Culture Medium without Phenol Red: To reduce background fluorescence during live-cell imaging.

- Membrane-Labeling Dyes (Optional): For visualizing cell boundaries.

- Micropatterned Substrates: Prepared as in Protocol 4.1, with patterns (e.g., "crossbow" or frames) designed to elicit specific, reproducible SFs.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells onto micropatterned substrates and culture until fully spread and polarized (typically 6-12 hours).

- Microscope Setup: Use a confocal or high-resolution epifluorescence microscope coupled with a pulsed laser ablation system (e.g., 355 nm laser). Maintain cells at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Fiber Selection and Severing: Identify a single, well-defined stress fiber. Target the laser to a precise point along the fiber and perform a single, brief pulse to sever it.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-speed time-lapse images (e.g., 100 ms intervals) immediately before and after ablation to capture the retraction dynamics of the severed fiber ends.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the initial retraction velocity and maximum displacement of the fiber ends. Use these parameters to calculate the prestress and viscoelastic properties stored within the fiber. Data can be fitted with mathematical models, such as a cable network model, to extract physical parameters [6].

Protocol: Investigating Cytoskeletal Dynamics in 3D Microenvironments

This protocol extends geometric control to three-dimensional systems by fully encapsulating cells within a 3D hydrogel [6] [7].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer Hydrogels (e.g., Collagen, Fibrin, or synthetic PEG-based): Provide a tunable 3D scaffold that mimics the native extracellular matrix.

- Crosslinking Agents: Enzymatic (e.g., thrombin for fibrin), chemical, or photo-initiators to polymerize the hydrogel.

- Soluble Factors/Growth Media: To support cell viability and proliferation within the 3D matrix.

Methodology:

- Cell-Hydrogel Mixture Preparation: Suspend cells at the desired density in the pre-polymerized hydrogel solution. Ensure homogeneous distribution.

- Polymerization: Transfer the cell-polymer mixture to a culture chamber (e.g., a glass-bottom dish) and induce gelation according to the specific hydrogel's protocol (e.g., temperature change, addition of crosslinker, UV light exposure).

- Culture and Imaging: Culture the 3D constructs in standard growth medium. For live-cell imaging, use confocal or light-sheet microscopy to visualize cytoskeletal dynamics and cell morphology deep within the gel.

- Analysis: Reconstruct 3D images to analyze actin architecture, network orientation, and cell-matrix interactions in a true 3D context.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Logic of Geometric Cue Transduction

Experimental Workflow for 2D Micropatterning

Actin Organization Response to Curvature

Actin Dynamics and Stress Fiber Formation in Response to Patterned Cues

The ability of cells to sense and adapt to their physical microenvironment is a cornerstone of cellular mechanobiology. Central to this process is the actin cytoskeleton, a dynamic network whose organization directly influences cell migration, differentiation, and overall function [9]. This application note details how micropatterned substrates serve as a powerful, controlled experimental platform to investigate actin dynamics and the subsequent formation of stress fibers—contractile actomyosin bundles that are critical for cellular mechanosensation and force transduction [10] [11].

Micropatterning allows researchers to dictate cell shape and adhesion geometry with high precision, thereby standardizing the physical cues presented to the cell. When combined with techniques like traction force microscopy, this platform enables the quantitative analysis of how specific geometric cues are translated into biochemical and mechanical signals that orchestrate the assembly, orientation, and contractile function of actin stress fibers [12] [11]. The protocols herein are designed for researchers aiming to dissect the signaling pathways and mechanical principles governing cytoskeletal reorganization, with direct applications in fundamental cell biology, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine.

Theoretical Background and Key Signaling Pathways

The formation of stress fibers is a tension-dependent process regulated by a complex interplay of biochemical signaling and physical forces. A primary regulator is the Rho family of GTPases, particularly RhoA, which integrates signals from cell adhesion and membrane tension to stimulate actin polymerization and myosin II-based contractility [9]. RhoA activation leads to the recruitment of formins, which nucleate and elongate actin filaments, and ROCK (Rho-associated kinase), which activates non-muscle myosin II (NMMII) by phosphorylating its regulatory light chain [9] [10]. This activation of NMMII generates the contractile forces necessary for the bundling of actin filaments into mature stress fibers.

The mechanical stability and force transmission capacity of stress fibers are profoundly influenced by actin-crosslinking proteins, most notably α-actinin and filamin. These crosslinkers solidify the actin network by reducing the internal mobility (flow) of actin and myosin filaments within the fiber. This solidification minimizes viscous energy dissipation and ensures that the contractile force generated by myosin is efficiently transmitted along the stress fiber to the focal adhesions at its ends [10] [13]. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway from initial adhesion to stress fiber maturation.

Beyond the well-established pathway of ventral stress fiber formation from pre-existing dorsal fibers and transverse arcs, recent research has identified an alternative mechanism for the de novo generation of stress fibers directly from the actin cortex. These "cortical stress fibers" assemble underneath the nucleus through a process orchestrated by stochastic pulses of non-muscle myosin IIA (NMIIA), which reorganize the isotropic actin meshwork into defined, focal adhesion-connected bundles [14]. This finding expands our understanding of stress fiber biogenesis and highlights the role of myosin dynamics in cytoskeletal patterning. The workflow below contrasts these two formation pathways.

Quantitative Models of Stress Fiber Kinetics

Mathematical modeling provides a quantitative framework for predicting how stress fibers respond to mechanical stimuli. Several complementary models have been developed, primarily differing in their assumptions about whether mechanical stress promotes fiber assembly or hastens disassembly [15].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Models of Stress Fiber Kinetics

| Model Name | Core Principle | Governing Equation / Kinetic Law | Predicted Cellular Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaunas et al. | Mechanical stretch accelerates the depolymerization of constantly turning over stress fibers. | Rate of SF disassembly increases with mechanical strain. | SFs align perpendicular to uniaxial stretch to minimize strain. |

| Deshpande et al. | Mechanical stress is required to activate SF formation and subsequently stabilize them. | dη(φ)/dt = [ (1-η(φ)) * C(t) * kf ] - [ (1 - σ(φ)/σ₀(φ)) * η(φ) * kb ] Where η(φ) is SF density, C(t) is activation signal, σ(φ) is tension, and σ₀(φ) is isometric stress [15]. |

SF assembly depends on stress; stable at isometric stress, disassemble at lower stress. |

| Lee et al. | A hybrid approach incorporating elements of both assembly and disassembly models. | Combines stress-dependent assembly and strain-dependent disassembly terms. | Predicts complex behaviors in 3D culture, including reinforcement, retraction, and adaptation. |

Computational models at the molecular level have further elucidated how molecular components govern stress fiber mechanics. Simulations using platforms like MEDYAN reveal that contractile force is positively correlated with the number of myosin motors and α-actinin crosslinkers [13]. A critical finding is that stress fibers can enhance their contractility by structurally remodeling to reduce the spacing between actin filaments, thereby increasing the binding of crosslinkers. Furthermore, a lower crosslinker turnover rate enhances both contractility and structural stability, as longer-lived crosslinks provide more robust mechanical integrity [13].

Table 2: Molecular Determinants of Stress Fiber Contractility from Computational Models

| Molecular Component | Simulated Parameter Variation | Impact on Steady-State Contractility (E_FA) | Impact on Stress Fiber Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Muscle Myosin II | Increased number of myosin motors. | Increase [13]. | Increased contractile force generation. |

| α-Actinin | Increased number of crosslinkers. | Increase [13]. | Reduced filament mobility, enhanced solidification. |

| α-Actinin Turnover Rate | Decreased unbinding rate (longer lifetime). | Increase [13]. | Increased structural stability and efficiency of force transmission. |

Essential Reagents and Research Tools

A standardized toolkit is essential for conducting reproducible research on micropatterning and actin dynamics. The following table catalogs key reagents and their specific functions in these experimental protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Micropatterning and Actin Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micropatterned Substrates | Defines cell adhesion geometry to standardize biomechanical inputs. | PDMS microposts or photolithographically-patterned glass/plastic coated with adhesion proteins like fibronectin [15] [11]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Proteins | Promotes specific integrin-mediated cell adhesion to the patterned areas. | Fibronectin, Collagen I, Laminin (Cortical SFs show a preference for fibronectin [14]). |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Probing specific signaling pathways in stress fiber formation. | ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632), Myosin II inhibitor (Blebbistatin), Rho activator (CN03). |

| Fluorescent Probes for Staining | Visualizing cytoskeletal and adhesion structures. | Phalloidin (F-actin), Antibodies for Vinculin/Paxillin (Focal Adhesions), Non-muscle Myosin IIA/B [12] [14]. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Reagents | Dynamic tracking of protein localization and turnover. | SiR-Actin, GFP-tagged actin/zyxin/α-actinin; FuGENE HD or Lipofectamine for transfection. |

| Crosslinker Antibodies / siRNAs | Functional studies of specific actin-crosslinking proteins. | Antibodies against α-Actinin, Filamin; siRNA for gene knockdown to fluidize SFs and reduce traction [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication and Cell Plating on Micropatterned Substrates

This protocol describes the process for preparing micropatterned surfaces and seeding cells for consistent analysis of stress fiber formation.

Substrate Fabrication/Procurement:

- Option A (Micropost Arrays): Fabricate polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) micropost arrays using soft lithography. The stiffness of the posts is controlled by their height and diameter, while their spatial arrangement defines the adhesion geometry [15] [11].

- Option B (2D Adhesive Patterns): Use commercial pre-patterned surfaces or create them in-house via deep UV photolithography or microcontact printing to create islands of adhesive proteins (e.g., fibronectin) surrounded by non-adhesive regions (e.g., PEGylated surface) [15].

Surface Coating:

- Incubate the micropatterned substrate with a solution of the desired ECM protein (e.g., 10 µg/mL fibronectin in PBS) for 1 hour at 37°C or overnight at 4°C.

- Rinse thoroughly with sterile PBS to remove unbound protein. Keep the substrate hydrated.

Cell Seeding and Incubation:

- Trypsinize and resuspend cells in complete growth medium.

- Seed cells onto the patterned substrate at a low density (e.g., 5,000 - 20,000 cells/cm²) to ensure a high probability of single cells adhering to individual patterns.

- Allow cells to adhere and spread for a defined period (typically 4-24 hours) in a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator before fixation or live-cell imaging.

Protocol: Immunofluorescence and Quantitative Image Analysis of Stress Fibers

This protocol covers the steps for fixing, staining, and quantitatively analyzing cells on micropatterns.

Cell Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Aspirate the culture medium and rinse cells gently with pre-warmed PBS.

- Fix cells with a 4% formaldehyde solution in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse with PBS three times for 5 minutes each.

- Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Rinse again with PBS three times.

Staining:

- Prepare a blocking solution (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS). Incubate cells for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Prepare primary antibody dilutions (e.g., anti-vinculin) and phalloidin conjugate in blocking solution.

- Aspirate the blocking solution and apply the staining solution. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Rinse thoroughly with PBS (3 x 10 minutes).

- If using a primary antibody, apply appropriate fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Rinse thoroughly with PBS (3 x 10 minutes). Include DAPI (1 µg/mL) in the second rinse to stain nuclei if desired.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire high-resolution z-stack images using a confocal or super-resolution microscope (e.g., 3D-SIM) with a 60x or 100x oil-immersion objective [14].

- Morphometric Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., NIS-Elements, Fiji) to measure cell spread area and circularity based on the phalloidin channel.

- Stress Fiber Quantification: Utilize custom computational tools (e.g., in Matlab) to automatically segment and count individual stress fibers. These tools typically combine information from the vinculin (focal adhesions) and phalloidin (actin) channels, identifying straight or slightly curved actin bundles that connect pairs of focal adhesions [12] [16].

- Protein Distribution: To compare protein localization independent of cell shape, employ distribution parameters like Radial Mean Intensity (RMI) or Local Ring Mean Intensity (LRMI) after normalizing cell morphology [16].

Protocol: Traction Force Microscopy (TFM) on Micropost Arrays

This protocol outlines the procedure for measuring cellular traction forces.

Preparation of Fluorescent Micropost Arrays:

- Use PDMS micropost arrays fabricated as in Protocol 5.1. To enable force visualization, treat posts with a fluorescent dye or embed fluorescent beads at their tips [11].

Cell Plating and Imaging:

- Seed cells onto the fluorescent micropost array as described in Protocol 5.1.

- Allow cells to adhere and spread for the desired time (e.g., 6-12 hours).

- Acquire two sets of images using a live-cell microscope:

- Images of the posts' deflection with the cell present.

- A reference image of the posts' undeflected positions after gently detaching the cell (e.g., using trypsin).

Traction Force Calculation:

- Use a Fourier transform-based algorithm or similar method to calculate the displacement field of the post tops between the deflected and reference states [12] [11].

- Calculate the traction force vectors based on the displacement of each post and the known spring constant of the microposts (determined by their geometry and the Young's modulus of PDMS). The total traction force is the sum of the magnitudes of all force vectors exerted by the cell.

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

- Pattern Fidelity: Inconsistent staining or poor pattern definition is often due to inadequate blocking or non-specific binding. Optimize the concentration of the blocking agent (BSA or serum) and ensure the non-adhesive coating (e.g., PEG) is intact.

- Low Efficiency of Single-Cell Patterning: This is typically caused by seeding cells at too high a density. Titrate the cell seeding number to maximize the number of patterns occupied by a single cell.

- Weak or Unclear Traction Force Signals: Ensure that the microposts are sufficiently flexible for measurable deflection under cell-generated forces. Characterize the spring constant of your posts and confirm that the fluorescent beads are precisely at the post tops.

- Interpreting Stress Fiber Subtypes: Remember that not all actin bundles are the same. Distinguish between ventral stress fibers (thick, contractile, connect two FAs), dorsal fibers (form at leading edge FAs, uniform polarity), transverse arcs (curved, non-attached, highly contractile), and the more recently identified cortical stress fibers (thin, de novo from cortex, low contractility) when analyzing your results [17] [14].

Microtubule Reorganization and Centrosome Positioning Guided by Cell Shape

Application Notes

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for investigating the relationship between engineered cell shape, microtubule reorganization, and subsequent centrosome positioning. These methods are central to a broader thesis exploring how micropatterning can be used to direct cytoskeleton organization, a critical consideration in fundamental cell biology and drug development research. Adherence to these protocols allows for the precise experimental manipulation and quantification of these processes.

The mechanical interplay between the actomyosin network and microtubules is fundamental to centrosome positioning. Recent research using laser-based nanoablation reveals that while forces along microtubules are dampened by their anchoring to the actin network, the actomyosin contractile network generates a centripetal flow that robustly drives the centrosome toward the cell's center [18]. Furthermore, the remodeling of cell shape around the centrosome, directed by the radial array of microtubules and cytoplasmic dyneins, is instrumental in this centering process [18].

Quantitative mapping of microtubule arrays, enabled by super-resolution techniques like STED microscopy, has revealed a sophisticated spatial organization within cells. For instance, in neuronal dendrites, acetylated (stable) microtubules form a core in the center, while tyrosinated (dynamic) microtubules are enriched near the plasma membrane, creating a core-shell structure [19]. This organization is crucial for regulating intracellular transport, as different motor proteins prefer specific microtubule subsets.

Table 1: Microtubule Dynamic Instability Parameters at Prophase/Nuclear Envelope Breakdown (NEBD) [20]

| Dynamic Parameter | Interphase | NEBD | Metaphase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate (μm/min) | 11.5 ± 7.40 | 10.7 ± 9.17 | 12.8 ± 5.66 |

| Shrinking Rate (μm/min) | 13.1 ± 8.43 | 12.3 ± 5.23 | 14.1 ± 7.86 |

| Shrinking Distance (μm) | 1.52 ± 1.77 | 4.00 ± 3.38 | 3.70 ± 3.83 |

| Average Pause Duration (s) | 25.5 ± 32.7 | 13.1 ± 14.5 | 9.31 ± 5.08 |

| Catastrophe Frequency (s⁻¹) | 0.026 ± 0.024 | 0.075 ± 0.089 | 0.058 ± 0.045 |

| Rescue Frequency (s⁻¹) | 0.175 ± 0.104 | 0.023 ± 0.029 | 0.045 ± 0.111 |

| Dynamicity (μm/min) | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 9.04 ± 3.95 | 14.6 ± 11.3 |

The following workflow diagram integrates the cellular phenomena with the experimental methods used to study them.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of PDMS Microstencils for Cell Confinement

This protocol describes the creation of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microstencils to control cell colony shape and investigate curvature-dependent effects [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PDMS Base and Curing Agent (e.g., Sylgard 184)

- Absolute Ethanol (75%)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile

Procedure:

- Punching: Use an engineered puncher with defined inner diameters (e.g., 800 μm and 1500 μm) to perforate a 100 μm-thick PDMS film, creating through-film stencils [3].

- Sterilization: Immerse the punched PDMS microstencils in 75% ethanol for 30 minutes to eliminate residual PDMS monomer and sterilize the surfaces [3].

- Washing: Wash the stencils with sterile PBS three times to remove all traces of ethanol [3].

- Plating: Place the sterilized PDMS microstencils into the wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, ensuring a tight seal with the substrate [3].

Protocol 2: Cell Seeding and Colony Formation on Microstencils

This protocol outlines the formation of human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) colonies with controlled density and geometry [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) (e.g., Lonza Walkersville Inc., 2F3478)

- Cell Culture Medium: Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS)

- EDTA/Trypsin solution for cell harvesting

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture hMSCs to 80% confluence. Harvest cells using EDTA/trypsin treatment, centrifuge at 300 g, and resuspend in culture medium to generate homogeneous cell suspensions at densities of 0.5 × 10⁵, 1.0 × 10⁵, and 2.0 × 10⁵ cells mL⁻¹ [3].

- Seeding: Add 1 mL of the cell suspension into the PDMS stencils adhered to the 24-well plate. The three seeding densities correspond to low, middle, and high-level colony densities [3].

- Colony Formation: Culture the cells for 6 hours, then refresh the medium with new DMEM culture medium. Continue culturing the hMSCs for a total of 18-24 hours to allow for the formation of stable colonies with defined spatial heterogeneity [3].

- Stencil Removal: After the colony formation period, carefully peel off the PDMS-based stencils to reveal the microcolony of hMSCs for downstream analysis [3].

Protocol 3: Immunofluorescent Staining for Cytoskeletal and Adhesion Components

This protocol details the staining procedure for visualizing focal adhesion proteins and the cytoskeleton to assess mechanotransduction.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS

- Permeabilization Buffer: 1% Triton X-100 in PBS

- Blocking Buffer: 2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-integrin, anti-vinculin, anti-talin-1, anti-acetylated tubulin, anti-tyrosinated tubulin

- Secondary Antibodies: Alexa Fluor-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488)

- Nuclear Stain: 4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI)

Procedure:

- Fixation: Wash the cell colonies with PBS and fix with 4% cold PFA for 15 minutes [3].

- Permeabilization: Treat the fixed cells with 1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes to permeabilize the cell membrane [3].

- Blocking: Incubate the cells with 2% BSA for 1 hour to block non-specific antibody binding [3].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply the desired primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer and incubate overnight at 4°C [3].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Wash the cells with PBS three times and incubate with the appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light [3].

- Nuclear Staining: Incubate with DAPI to visualize cell nuclei [3].

- Imaging: Capture images using fluorescence or confocal microscopy. For high-resolution analysis of microtubule arrays, employ super-resolution techniques such as STED microscopy [19].

Protocol 4: Quantitative Analysis of Cytoskeletal Organization

This protocol describes methods for quantifying cytoskeleton density and organization from acquired images.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Image Analysis Software: (e.g., ImageJ/FIJI, commercial packages with segmentation tools)

Procedure:

- Density Calculation: Use ImageJ to calculate cell density within each microcolony from DAPI-stained images. Distinguish between the central and peripheral areas of the colony for regional analysis [3].

- Radial Distribution Mapping: For dendrites or other cellular structures, build radial distribution maps of fluorescence intensity for different microtubule subsets (e.g., acetylated vs. tyrosinated) to quantify their spatial organization [19].

- AI-Powered Segmentation (Advanced): Utilize deep learning-based segmentation models, trained on hundreds of confocal microscopy images, to achieve high-throughput, accurate measurement of cytoskeleton density, surpassing the limitations of conventional techniques [21].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Research Reagent | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| PDMS Microstencils | Defines the physical boundaries for cell growth, creating colonies with specific curvature and geometry to study interfacial heterogeneity [3]. |

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | A primary cell model responsive to biomechanical cues; used to study density and curvature effects on focal adhesion and nuclear mechanotransduction [3]. |

| Anti-Vinculin / Anti-Talin-1 Antibodies | Immunofluorescent labeling of focal adhesion complexes to evaluate their expression levels and distribution in response to engineered microenvironments [3]. |

| Anti-Acetylated Tubulin Antibody | Labels stable, long-lived microtubules; used in super-resolution microscopy to map the "core" microtubule network [19]. |

| Anti-Tyrosinated Tubulin Antibody | Labels dynamic, newly-polymerized microtubules; used in super-resolution microscopy to map the "shell" microtubule network [19]. |

| Deep Learning Segmentation Model | AI-based tool for high-precision, high-throughput quantification of cytoskeleton density from microscopy images, automating a traditionally error-prone process [21]. |

In the field of developmental biology and tissue engineering, a fundamental question persists: how do initially identical cells break symmetry and establish complex, polarized structures? Micropatterning technology provides a powerful tool to answer this question by offering unprecedented precision in controlling the cellular microenvironment [1]. This technique allows researchers to precisely manipulate the spatial distribution of cell adhesion proteins on various substrates, thereby imposing defined physical constraints on single or multiple cells [1].

The ability to control cell geometry through micropatterning has revealed that physical confinement is not merely a passive backdrop but an active instructor of cell fate and tissue organization. When combined with studies of cytoskeleton organization, this approach has become indispensable for unraveling how mechanical cues are transduced into biochemical signals that guide cellular behavior. This protocol details the application of micropatterned surfaces to investigate the fundamental mechanisms by which pattern geometry instructs cellular polarity and symmetry breaking, providing a controlled in vitro system to deconstruct the complex processes of morphogenesis.

Theoretical Background: Geometry as a Morphogenetic Regulator

The Role of Geometric Confinement in Symmetry Breaking

Geometric confinement operates by creating spatial heterogeneities within a cell population, effectively breaking symmetry by establishing position-dependent signaling environments. In practice, confining human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) to 2D micropatterns generates a spatially organized signaling milieu in a highly controllable and reproducible manner, leading to regionalized cell fate patterning [22]. For instance, when hPSCs are cultured on circular micropatterns under caudalizing signals, a remarkable self-organization phenomenon occurs: cells at the colony center adopt a neural fate (SOX2-positive), while those at the periphery acquire mesodermal characteristics (T-positive) [22]. This patterning emerges through the interplay between the self-organizing capacity of the cells and the cues provided by the geometric boundaries.

The initial symmetry breaking event often triggers a cascade of morphogenetic processes. In the case of geometrically confined hPSC colonies, the segregation of center and edge cells coincides with mechanical force redistribution, where cells at the edge develop inward pulling forces while high tension develops in the middle where cells aggregate and polarize [22]. This differential force distribution ultimately leads to three-dimensional morphogenesis, such as center protrusion, demonstrating how initial geometric cues can propagate through mechanical and biochemical feedback loops to drive complex tissue-level organization.

Cytoskeletal Mediation of Geometric Cues

The cytoskeleton serves as the primary cellular machinery for interpreting geometric constraints. Studies combining micropatterning with traction force microscopy have revealed that cells exhibit position-dependent collective behaviors that can be regulated by both geometry and substrate stiffness [23]. The driving force for these behaviors appears to be the in-plane maximum shear stress within the cell layer, which directs cell arrangement and polarization [23].

The relationship between substrate geometry and cytoskeletal organization follows quantifiable mechanical principles. Cells preferentially align and polarize along the direction of the maximum principal stress, with the degree of alignment exhibiting a biphasic dependence on substrate rigidity [23]. This mechanical feedback system allows cells to collectively integrate geometric information across multiple scales, from subcellular actin organization to tissue-level patterning.

Figure 1: Signaling Pathway of Geometric Symmetry Breaking. This diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathway through which geometric confinement leads to cellular symmetry breaking and tissue patterning, integrating physical cues with biochemical responses.

Key Experimental Findings and Quantitative Data

Quantitative Effects of Pattern Geometry on Cell Patterning

The systematic analysis of cellular responses to geometric confinement has yielded quantifiable relationships between pattern parameters and cell behavior. Research has demonstrated that the initial size of micropatterns directly controls the proportional outcomes of differentiated cell types.

Table 1: Effects of Micropattern Geometry on Cell Patterning and Differentiation

| Pattern Geometry | Cell Type/System | Key Measured Outcome | Quantitative Result | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circular (350µm diameter) | Human Pluripotent Stem Cells | Dorsal/Ventral Domain Proportion | Controlled by initial micropattern size [22] | Enables control over tissue patterning ratios |

| Ring/Appositional Boundaries | Various Cell Types | Chirality (Left-right bias) | Cell phenotype-dependent handedness [24] | Recapitulates developmental left-right asymmetry |

| Variable Stiffness Substrates | Osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 Cells | Cell Polarization Aspect Ratio | Biphasic dependence on substrate rigidity [23] | Optimal stiffness ranges for polarization |

| Geometric Confinement | Human Pluripotent Stem Cells | Spatial Segregation of SOX2/T | Center: SOX2+ (neural); Edge: T+ (mesoderm) [22] | Mimics early germ layer segregation |

Mechanical Stress Measurements in Patterned Cells

The mechanical environment within geometrically constrained cells provides critical insights into the force-based mechanisms underlying symmetry breaking. Traction force microscopy measurements have revealed consistent relationships between pattern-induced stresses and cell behaviors.

Table 2: Mechanical Stress Parameters and Cell Behavioral Outcomes

| Mechanical Parameter | Measurement Technique | Correlated Cellular Behavior | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Shear Stress | Traction Force Microscopy + FEM Analysis | Degree of Cell Alignment | Micropatterned MC3T3-E1 cells [23] |

| Traction Force Distribution | Constrained Fourier Transform Traction Microscopy | Position-Specific Morphology | Collective cell behaviors on patterns [23] |

| Cellular Prestress | Finite Element Modeling (ε₀ ~ 0.1) | Cytoskeletal Tension Regulation | Homogeneous elastic membrane model [23] |

| In-plane Principal Stress | Finite Element Analysis | Direction of Cell Polarization | Various geometric patterns [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microcontact Printing for Micropatterned Well Plates

The μCP Well Plate platform adapts the spatial control of traditional microcontact printing to the format of standard multiwell plates, enabling high-content screening with precise geometric control [25].

Materials and Reagents

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps fabricated from silicon master molds

- Epoxy-coated coverslips or gold-coated glass sheets (116 mm × 77 mm × 0.2 mm)

- Sylgard 184 elastomer kit (Dow Corning)

- Alkanethiol solution (2mM in ethanol) for self-assembled monolayers

- PEG-based reaction solution for non-adhesive regions

- Multi-well alignment device (computer-numerical control machined aluminum)

- Double-sided adhesive (ARcare 90106) for well plate assembly

- Oxygen plasma system for hydrophilic stamp treatment

- Extracellular matrix proteins (e.g., collagen, fibronectin) for adhesive regions

Fabrication Procedure

Stamp Preparation: Pour degassed Sylgard 184 elastomer (10:1 base:curing agent ratio) onto silicon master molds. Place a transparency sheet and flat weight on top to ensure consistent height. Cure overnight at 37°C [25].

Surface Functionalization: Treat PDMS stamps with oxygen plasma to render hydrophilic. Apply a thin layer of 2mM alkanethiol ethanol solution evenly over the stamp surface and allow to air dry [25].

Pattern Transfer: Place the functionalized stamp face-up in the alignment device. Lower the gold-coated glass sheet onto the stamp using vacuum tooling for controlled contact and pattern transfer [25].

PEG Brush Growth: Incubate patterned sheets with PEG reaction solution (20 mL) containing L-Ascorbic acid initiator (164 mg in 1.82 mL deionized water) under nitrogen atmosphere for 16 hours at room temperature [25].

Well Plate Assembly: Seal the patterned glass sheet to the well plate frame using double-sided adhesive in the alignment device. Sterilize with 70% ethanol bath before cell seeding [25].

Protocol 2: Geometric Confinement for Spinal Cord Organoid Polarization

This protocol generates polarized spinal cord organoids (pSCOs) with self-organized dorsoventral (DV) organization using geometric confinement to initiate symmetry breaking [22].

Materials and Reagents

- Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)

- Matrigel-coated micropatterned surfaces (350µm diameter circles)

- SB431542 (SB) 10 µM (TGF-β/Activin inhibitor)

- CHIR99021 (Chir) 3 µM (Wnt activator)

- Rac GTPase inhibitor (NSC23766) for perturbation studies

- Accutase solution for cell detachment

- Ultralow attachment 96-well plates for 3D culture

- Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) for neural maintenance

- Immunostaining antibodies: SOX2, T (Brachyury), NCAD, β-catenin, Slug

Procedure

Micropattern Preparation: Generate circular micropatterns (350µm diameter) of matrigel on glass coverslips using microcontact printing [22].

Cell Seeding and Caudalization: Seed hPSCs onto micropatterns at optimized density (avoid complete confluence). Treat with SB431542 (10 µM) and CHIR99021 (3 µM) for 3 days to induce caudal neural differentiation [22].

Spatial Patterning Analysis: At day 2 (SC-D2), assess spatial segregation via immunostaining. Expect SOX2-positive cells at colony centers and T-positive cells at edges [22].

Protrusion Formation and 3D Transition: At SC-D3, gently lift differentiated colonies with center protrusions using non-enzyme-based depolymerizing solution. Transfer detached colonies to ultralow attachment 96-well plates [22].

Organoid Maturation: Culture pSCOs with continuous medium supplementation (including bFGF) for up to 60 days, monitoring self-ordered DV patterning along the long axis [22].

Expected Results

- Day 1: Emergence of neuromesodermal cells co-expressing SOX2 and T [22]

- Day 2: Clear regional segregation with SOX2+ centers and T+ edges [22]

- Day 3: Visible center protrusion and differential traction forces [22]

- Week 4-8: Mature pSCOs with functional dorsal and ventral domains exhibiting synchronized neural activity [22]

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Geometric Symmetry Breaking. This diagram outlines the key steps in using micropatterning to study geometry-induced symmetry breaking, from surface fabrication to 3D morphogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of geometric symmetry breaking studies requires specific reagents and tools designed to create and analyze patterned cellular environments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Micropatterning Studies

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sylgard 184 Elastomer Kit | Dow Corning | PDMS stamp fabrication | 10:1 base to curing agent ratio optimal for stamp flexibility and durability [25] |

| Alkanethiol Solutions | Prochimia Surfaces | Formation of self-assembled monolayers on gold | 2mM concentration in ethanol for optimal pattern transfer [25] |

| Extracellular Matrix Proteins | Corning, Sigma | Cell-adhesive regions on patterns | Matrigel, collagen I, or fibronectin used at tissue culture concentrations [22] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Tocris, Sigma | Pathway modulation during patterning | SB431542 (10µM), CHIR99021 (3µM) for neural patterning [22] |

| Microcontact Printing Stamps | FlowJEM, CYTOO | Pattern definition | Feature sizes ≥1µm; regular dot arrays (3µm with 3µm interspaces) common [26] |

| Functionalized Coverslips | Schott, Coresix | Pattern substrate | NEXTERION E epoxy-coated or gold-coated (18nm) glass [26] [25] |

| Non-Adhesive Polymer Solutions | Various | Background passivation | PEG-based brushes effectively resist protein adsorption and cell attachment [25] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Pattern Fidelity and Reproducibility

Maintaining consistent pattern features across experiments requires careful attention to stamp fabrication and storage conditions. PDMS stamps should be thoroughly cleaned with acetone and alcohol in a bath sonicator between uses to prevent feature degradation [23]. Inconsistent pattern transfer often results from incomplete drying of alkanethiol solutions or uneven pressure application during stamping. Using a calibrated alignment device with consistent weighting ensures reproducible pattern transfer across multiple substrates [25].

Cell Seeding Optimization

Achieving the appropriate cell density on micropatterns is critical for successful symmetry breaking. Over-confluent seeding prevents center protrusion formation in hPSC patterning, while insufficient density hinders collective behaviors [22]. For 350µm diameter patterns, initial seeding should achieve approximately 70-80% confluence before differentiation induction. Accutase treatment provides superior single-cell suspension compared to trypsin for sensitive stem cell populations [22] [26].

Mechanical Microenvironment Control

Substrate stiffness significantly influences cellular responses to geometric cues. Polyacrylamide gels with tunable elastic moduli can be micropatterned to decouple geometric from mechanical effects [23]. The biphasic dependence of cell polarization on substrate rigidity means that both excessively soft and stiff substrates may yield suboptimal symmetry breaking, necessitating empirical optimization for each cell type [23].

Micropatterning technology has established geometric confinement as a fundamental regulator of cellular symmetry breaking and polarity establishment. The protocols and data presented herein provide a framework for systematically investigating how physical boundaries direct cell fate decisions through integrated mechanical and biochemical signaling networks. The ability to control pattern geometry with micron-scale precision offers unprecedented opportunities to deconstruct developmental processes and engineer tissue-like structures with defined organizational axes. As these techniques continue to evolve, particularly through integration with high-content screening platforms, they promise to accelerate both basic discovery in cytoskeleton organization and applied innovations in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

The Link Between Cytoskeletal Architecture and Fundamental Cell Functions (Division, Growth, Differentiation)

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic, polymeric network of filamentous proteins that is fundamental to cellular life. Far from being a simple structural scaffold, it is a central regulator of cell division, growth, and differentiation. Its components—actin microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—undergo continuous remodeling to provide mechanical stability, organize intracellular space, generate force for movement, and facilitate intracellular transport [27] [28]. In recent years, micropatterning technologies have emerged as a powerful tool to dissect these complex functions. By controlling cell adhesion geometry at the micron scale, researchers can standardize cell shape and cytoskeletal organization, transforming a heterogeneous cell population into a reproducible experimental model [29] [30]. This application note, framed within broader thesis research on micropatterning, details how these approaches can unravel the cytoskeleton's role in fundamental cell processes, providing detailed protocols and resources for researchers and drug development professionals.

Key Cytoskeletal Components and Their Functions

The cytoskeleton is composed of three primary filament systems, each with distinct structural and functional properties. The table below summarizes their characteristics and roles in core cellular functions.

Table 1: Core Components of the Cytoskeleton and Their Functions

| Filament Type | Protein Subunits | Key Characteristics | Role in Division | Role in Growth & Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin Microfilaments | Actin (e.g., ACTC1) | Dynamic polymers forming bundles and networks; regulated by ADF/cofilin, Arp2/3 [27]. | Forms the contractile ring for cytokinesis [27]. | Generates protrusive forces for cell migration; essential for tip growth in pollen tubes and root hairs [31] [32]. |

| Microtubules | α/β-Tubulin | Hollow, polarized tubes; highly dynamic; organized by MTOC [27]. | Forms mitotic spindle for chromosome segregation [27] [29]. | Tracks for intracellular transport; regulates cell polarity and differentiation [29] [31]. |

| Intermediate Filaments | Desmin, Vimentin | Ropelike, flexible; provide mechanical strength [27]. | Maintains nuclear and organellar integrity during division. | Maintains structural integrity; buffering mechanical and redox stress [27]. |

Experimental Protocols: Micropatterning for Cytoskeletal Studies

Micropatterning allows for precise control over the cellular microenvironment, enabling quantitative analysis of cytoskeletal organization and its functional consequences. The following protocol is adapted from studies on immune cells and macrophages [29] [30].

Protocol: Micropatterning of Adherent Cells for Cytoskeleton Analysis

I. Primary Equipment and Reagents

- Micropatterned Substrates: Commercial CytooChips (e.g., L, crossbow, or nanoridge patterns) or custom-fabricated substrates using Multiphoton Absorption Polymerization (MAP) [29] [30].

- Cell Culture Reagents: Appropriate cell culture medium, fetal calf serum, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamine.

- Coating Protein: Fibronectin or other extracellular matrix proteins.

- Fixation and Staining: Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Triton X-100, blocking buffer (e.g., BSA), fluorescently-labeled phalloidin (for F-actin), anti-tubulin antibodies (for microtubules), and DAPI (for nuclei).

- Imaging System: High-resolution fluorescence microscope (e.g., with TIRF or iSIM capabilities) [29].

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Substrate Preparation:

Cell Seeding and Spreading:

- Harvest and resuspend cells (e.g., macrophages, Jurkat T cells) in complete medium at a density of 50,000 cells/mL [30].

- Seed the cell suspension onto the coated micropatterned coverslips.

- Incubate for 60 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO₂ to allow for initial adhesion.

- Gently flush with fresh medium to remove non-adherent cells.

- Return to the incubator for an additional 4-6 hours to allow for full spreading and cytoskeletal adaptation to the pattern [30].

Experimental Intervention:

- Apply the experimental treatment (e.g., toxin exposure, drug addition, signaling pathway inhibitor).

- Example: To study the effect of Bacillus anthracis edema toxin (ET), treat cells with a combination of Protective Antigen (PA) and Edema Factor (EF) and incubate for up to 16 hours [30].

Fixation and Immunostaining:

- At the desired time point, wash cells with PBS and fix with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes.

- Block non-specific binding with 1-3% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes.

- Stain for cytoskeletal components: incubate with rhodamine-phalloidin (1:100) to label F-actin and/or primary antibodies against tubulin for microtubules for 1 hour [29] [30].

- Wash and apply secondary antibodies if needed. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Image cells using high-resolution microscopy (e.g., iSIM or TIRF). Ensure consistent imaging parameters across all conditions.

- Quantify cytoskeletal organization using metrics such as:

- Actin Fluorescence Intensity: Calculate peak-to-mean (PtoM) ratios to quantify accumulation near topographic features [29].

- Cell Spread Area and Morphology: Analyze the contact area and shape descriptors (e.g., eccentricity) [29].

- Nuclear Positioning: Measure the distance from the nucleus to specific cellular landmarks.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps of the micropatterning protocol and its application in studying cytoskeletal responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful cytoskeletal research relies on a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential solutions for micropatterning-based studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Micropatterning and Cytoskeletal Analysis

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micropatterned Substrates | CytooChips (L, crossbow shapes) [30]; Nanoridge substrates (1-5 μm spacing) [29] | Controls cell adhesion geometry, standardizing cytoskeletal organization for quantitative analysis. | Fundamental studies on how topography influences actin dynamics and signaling in T cells and macrophages. |

| Cytoskeletal Probes | Rhodamine-phalloidin; Anti-α/β-tubulin antibodies; EGFP-EB3 (for dynamic MT imaging) [29] | Labels F-actin, microtubules, and tracks growing microtubule ends, respectively. | Standard immunofluorescence and live-cell imaging to visualize cytoskeletal architecture and dynamics. |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Latrunculin B (F-actin depolymerizer) [32]; Oryzalin (microtubule depolymerizer) [32] | Dissects the specific roles of actin or microtubules in processes like nuclear migration and cell division. | Used in plant systems (e.g., Arabidopsis) to show pre-division nuclear migration is MT-dependent [32]. |

| Signaling Pathway Tools | Edema Toxin (ET: PA + EF) [30]; ROP GTPase pathway activators/inhibitors [31] | Modulates intracellular cAMP; manipulates key upstream regulators of actin reorganization in plant and animal cells. | ET used to study cAMP-mediated cytoskeletal collapse in macrophages [30]. ROP tools used in plant cell polarity studies [31]. |

| Computational Tools | Subcellular Element (SCE) modeling [33]; Machine Learning (SVM classifiers) [28] | Models multicellular tissue mechanics and shape; identifies cytoskeletal gene signatures from transcriptomic data. | SCE models simulate wing disc development [33]. ML identifies cytoskeletal genes linked to age-related diseases [28]. |

Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Core Cellular Functions

Cell Division: The Cytoskeletal Machinery of Proliferation

Cell division is a cytoskeleton-intensive process. In mitosis, microtubules form the bipolar spindle to segregate chromosomes, while actin, in conjunction with myosin, forms the contractile ring that cleaves the cytoplasm during cytokinesis [27]. In specialized cells, the cytoskeleton also orchestrates asymmetric cell division (ACD), which generates daughter cells with distinct fates.

In plants, ACD is often preceded by directional nuclear migration, directed by polar cytoskeletal rearrangements. Research in maize subsidiary mother cells (SMCs) has revealed a hierarchical polarity pathway where BRICK1 (BRK1) and PANGLOSS (PAN) receptors recruit ROP GTPases to activate the Arp2/3 complex, forming a polar F-actin patch. This patch directs nuclear migration towards the immune synapse, a process requiring the linker protein MLKS2 [32]. Conversely, in the Arabidopsis stomatal lineage, the polarity protein BASL creates a cortical domain that locally destabilizes microtubules, repelling the nucleus before division in a microtubule-dependent manner [32]. This highlights the cell-type-specific use of different cytoskeletal components to achieve a similar outcome—oriented division.

Cell Growth: Cytoskeletal Regulation of Morphogenesis

The cytoskeleton is a principal architect of cell shape and tissue morphology during growth. In tip-growing cells like pollen tubes and root hairs, actin filaments are organized into distinct structures: longitudinal bundles in the shank facilitate cytoplasmic streaming, while a dynamic mesh of shorter filaments at the apex directs vesicle delivery for polarized growth [31]. Microtubules, while absent from the extreme tip, provide tracks for long-distance transport and help maintain growth directionality [31].

At the tissue level, the development of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc exemplifies how the interplay between cytoskeletal regulation and proliferation shapes an organ. Computational modeling (Subcellular Element modeling) calibrated with experimental data shows that tissue curvature and cell height are controlled by the spatial patterning of actomyosin contractility, cell-ECM adhesion, and ECM stiffness. Furthermore, different growth-promoting pathways (e.g., Insulin vs. Dpp/Myc signaling) can have distinct effects on tissue shape because they differentially influence the cytoskeleton, demonstrating a coupled regulation of growth and structural organization [33].

Cell Differentiation: Structural and Metabolic Specialization

Differentiation often involves a profound reorganization of the cytoskeleton to support specialized functions. A prime example is cardiomyocyte maturation. During postnatal development, cardiomyocytes exit the cell cycle and undergo extensive cytoskeletal remodeling to form highly organized sarcomeres, the contractile units of the heart [27]. This is accompanied by a stabilization of the microtubule network and increased expression of adult isoforms of contractile proteins like cardiac troponin I (TNNI3) [27]. This structural specialization, while essential for contractile function, creates a barrier to cell division, contributing to the heart's limited regenerative capacity. Research shows that targeted disassembly of these cytoskeletal structures can promote cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and re-entry into the cell cycle, highlighting the cytoskeleton's role in maintaining the differentiated state [27].

Table 3: Quantitative Cytoskeletal Parameters in Model Systems

| Model System / Process | Measurable Parameter | Typical Value / Observation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| T Cell Activation on Nanoridges [29] | Cell Spread Area (after 6 min) | Smaller on 1μm ridges vs. flat surfaces | Nanotopography globally limits spreading but locally enhances signaling. |

| Actin Peak-to-Mean (PtoM) Ratio | Significantly higher on all ridge spacings vs. flat | Actin accumulation at topographic features enhances signaling molecule (e.g., ZAP-70) recruitment. | |

| Drosophila Wing Disc Development [33] | Basal Curvature (κ_basal) | Flattens in medial domain from 84-96 h AEL | Spatially patterned cytoskeletal regulators (pMyoII, βPS) drive complex tissue shaping. |

| Ratio of Apical/Basal pMyoII | Correlates with tissue height at later stages | Balance of apical-basal contractility is a key determinant of cell and tissue morphology. | |

| Cardiomyocyte Maturation [27] | Binucleation (in mice) | ~90% by Postnatal Day 14 (P14) | Marker of cell cycle exit and terminal differentiation. |

| Metabolic Shift | Oxidative Phosphorylation Glycolysis | A return to glycolysis is associated with dedifferentiation and proliferation potential. |

Key Signaling Pathways: From Cue to Cytoskeletal Reorganization

The cytoskeleton integrates signals from multiple pathways to direct cellular outcomes. Two key pathways are illustrated below.

ROP GTPase Signaling in Plant Cell Polarity:

Hippo/YAP Signaling in Mechanotransduction and Growth:

A Practical Guide to Micropatterning Techniques and Their Research Applications

In the field of cell biology, particularly in studies focused on cytoskeleton organization, the ability to control the cellular microenvironment is paramount. Micropatterning technologies have emerged as powerful tools that allow researchers to dictate cell adhesion with micron-scale precision, thereby normalizing cell shape and internal architecture. This control is crucial for investigating how physical cues influence complex cellular processes such as cytoskeletal rearrangement, polarization, and differentiation [34] [35]. Among the available techniques, microcontact printing and maskless photopatterning (exemplified by the PRIMO system) represent two foundational approaches. This article provides a detailed comparative overview of these technologies, framing them within the context of cytoskeleton organization studies and providing application-focused notes and protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Technology Comparison: Core Principles and Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate micropatterning technique is a critical first step in experimental design. The core principles, advantages, and limitations of microcontact printing and maskless photopatterning are distinct, making each suitable for different experimental needs.

Microcontact printing (μCP) is a well-established method that utilizes a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomeric stamp, fabricated from a lithographed master, to physically transfer cell-adhesive proteins onto a substrate [34] [36]. The process involves incubating the stamp with a protein solution, followed by contact-based inking of the substrate to create defined adhesive regions. In contrast, maskless photopatterning, such as the Light-Induced Molecular Adsorption of Proteins (LIMAP) method using the PRIMO system, is a digital and optical technique. This method involves coating a substrate with an anti-fouling layer (e.g., polyethylene glycol, PEG) and a photo-initiator. A UV laser, controlled by a digital micromirror device (DMD), is then used to locally remove the PEG layer via photoscission, exposing regions where proteins can subsequently adsorb to create the pattern [36]. A key differentiator is that LIMAP does not require a physical photomask, granting unparalleled flexibility in pattern design.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Micropatterning Technologies

| Feature | Microcontact Printing (μCP) | Maskless Photopatterning (PRIMO/LIMAP) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Physical transfer of proteins using a PDMS stamp [34] [36] | Digital, maskless removal of an anti-fouling layer via UV photoscission to allow protein adsorption [36] |

| Typical Resolution | Micron-scale [36] | Micron-scale [36] |

| Pattern Flexibility | Low; requires new master and stamp for each new pattern [36] | High; patterns are digitally designed and can be rapidly changed [36] |

| Multi-Protein Patterning | Challenging, typically requires multiple alignment steps | Yes; straightforward through repeated cycles of PEG removal and protein coating [36] |

| Protein Gradients | Difficult to achieve | Yes; possible by varying laser power [36] |

| Initial Setup Cost | Lower | Higher (equipment investment) [36] |

| Throughput | High for a single, fixed pattern | High for complex and variable patterns |

| Best Suited For | Experiments requiring high-throughput replication of a single, simple pattern | Experiments requiring high flexibility, multi-protein patterns, gradients, or complex geometries [36] |

Application Notes for Cytoskeleton Organization Studies

The normalization of cell shape through micropatterning directly dictates the organization of the intracellular actin cytoskeleton. By systematically positioning cell adhesion contacts, researchers can create highly reproducible and homogeneous actin architectures across a cell population [35] [37]. This normalization is transformative for quantitative cell biology, as it drastically reduces cell-to-cell variability, a significant bottleneck in high-content analysis and drug screening [35].