High-Throughput Actin Filament Quantification: Advanced Algorithms for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

The quantification of actin filaments provides critical insights into fundamental cellular processes and disease mechanisms.

High-Throughput Actin Filament Quantification: Advanced Algorithms for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

The quantification of actin filaments provides critical insights into fundamental cellular processes and disease mechanisms. This article explores the latest computational algorithms designed for high-throughput, accurate analysis of filamentous actin (F-actin) from microscopy images and biochemical assays. We cover foundational concepts of actin biology and imaging, detail cutting-edge methodologies including convolutional neural networks for segmentation and keypoint detection, and provide troubleshooting guidance for common challenges like dense filament networks and image noise. The article also presents rigorous validation techniques and comparative performance analysis of available tools, offering researchers and drug development professionals a comprehensive resource to implement robust, automated actin quantification in their work.

The Essential Role of Actin Quantification in Cell Biology and Biomedical Research

Why Actin Filament Dynamics Are Crucial for Cellular Function

The actin cytoskeleton is a fundamental component of eukaryotic cells, indispensable for a vast array of cellular processes. Actin filaments (F-actin) are dynamic structures assembled from globular actin monomers (G-actin), and their continuous, regulated assembly and disassembly—collectively termed actin dynamics—govern cell shape, motility, division, intracellular trafficking, and signal transduction [1] [2]. Beyond these cytoplasmic roles, actin also participates in critical nuclear functions, including transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, and DNA repair [1] [2]. The dynamics of these filaments are not random but are tightly controlled by a diverse repertoire of actin-binding proteins (ABPs), which nucleate, elongate, cap, sever, and depolymerize filaments in response to cellular signals [1] [3]. Understanding these dynamics is not merely a biological curiosity; it is essential for elucidating the mechanisms of disease, from cancer metastasis to immunodeficiency, and for developing novel therapeutic strategies [1] [4].

Core Principles and Key Regulatory Mechanisms

The Actin Dynamic Cycle

The assembly and turnover of actin filaments follow a structured cycle involving several key steps [1]:

- Nucleation: The formation of a stable actin trimer, which is the rate-limiting step. This process is facilitated by nucleators like the Arp2/3 complex, which creates branched filament networks, and formins, which promote the growth of linear filaments.

- Elongation: The rapid addition of ATP-bound G-actin to the growing barbed end of the filament. This step is accelerated by proteins like formins, which remain processively associated with the barbed end.

- ATP Hydrolysis: Following polymerization, ATP bound to actin within the filament is hydrolyzed to ADP, altering the filament's conformation and stability.

- Disassembly: The dissociation of ADP-actin from the pointed end, a process catalyzed by depolymerizing factors such as cofilin. The released ADP-actin exchanges ADP for ATP, re-entering the monomeric pool for a new round of polymerization.

This continuous cycle results in a phenomenon known as "treadmilling," where monomers add at the barbed end and dissociate from the pointed end, creating a steady-state flow that allows the filament to maintain a constant length while renewing its constituents [1].

Mechanisms of Actin Filament Regulation

Eukaryotic cells employ multiple, hierarchical mechanisms to ensure the spatiotemporal control of actin dynamics, allowing a single protein species to perform myriad functions. These mechanisms can be categorized as follows [2]:

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms Regulating Actin Filament Functions

| Mechanism | Key Players | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|

| Local Biochemical Regulation of ABPs | NPFs (WASP, WAVE), Rho GTPases (Rac1, Cdc42, RhoA), PIP2/PIP3 lipids | Directs localized actin assembly for front-rear cell polarity, lamellipodia, and filopodia formation [4] [2]. |

| Filament Conformation-Dependent Selection | ATP-/ADP-Pi-/ADP-actin states, cofilin, coronin | Targets specific ABPs to filaments of different ages or mechanical states, promoting network turnover [5] [2]. |

| Physical Geometry-Dependent Selection | Arp2/3 complex (70° branch angle) | Creates specific branched architectures that dictate the physical properties of the actin network [2]. |

These regulatory paradigms work in concert to assemble functionally distinct actin structures from a common pool of monomers and ABPs. For instance, the local activation of the Arp2/3 complex by WASP at the cell membrane leads to the formation of a branched actin network that drives lamellipodia protrusion, while the activation of formins by Rho GTPases generates bundled linear filaments for stress fibers and contractile rings [4] [2].

Diagram 1: The Actin Dynamic Cycle and Key Points of Regulation.

Quantitative Analysis of Actin Dynamics: Experimental and Computational Tools

The advent of high-resolution microscopy and sophisticated computational tools has transformed the study of actin from qualitative descriptions to precise, quantitative measurements. This is particularly critical in the context of high-throughput research aimed at deciphering the complex effects of multiple ABPs.

High-Throughput Filament Analysis with ATLAS

The In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA), where surface-bound myosin motors propel fluorescent actin filaments, is a powerful system for studying actomyosin kinetics. ATLAS (Automated Tracking of Learned Actin Structures) is an open-source software that overcomes the limitations of slow and biased manual analysis by employing state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms to automatically identify, track, and analyze the motion of hundreds of actin filaments in IVMA videos [6] [7]. It provides highly accurate measurements of two critical parameters: filament velocity and filament length, which report on the chemomechanical activity of the motor proteins [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Actin Dynamics Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phalloidin (Fluorescent) | Staining Reagent | Binds and stabilizes F-actin; used for visualization. | Fixed-cell imaging of actin architecture (SRRF, SIM, ExM) [8] [9]. |

| Lifeact | Live-Cell Probe | Peptide that binds F-actin without stabilizing it. | Live-cell imaging of actin dynamics [8]. |

| Recombinant Actin | Protein | Purified actin for in vitro reconstitution experiments. | IVMA, polymerization kinetics assays [6] [3]. |

| Cytochalasin D | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibits actin polymerization by capping barbed ends. | Disrupting cortical actin to study its functional role [9]. |

| ATLAS | Software | Machine learning-based analysis of filament motion. | High-throughput analysis of IVMA data [6] [7]. |

| FAST | Software | Deep learning-based segmentation of actin structures. | Quantifying actin organization from super-resolved images [8]. |

A Generalized Theoretical Framework for Multicomponent Regulation

While the roles of individual ABPs are well-characterized, how dozens of ABPs work together in vivo remains a major open question. A unified theoretical framework has been developed to bridge this gap. This kinetic model can incorporate the combined effects of an arbitrary number of regulatory proteins on actin filament dynamics [3] [10]. The model treats a filament as stochastically transitioning between different states (e.g., bound to formin, capping protein, or depolymerizing factor), with each state having a characteristic polymerization or depolymerization rate. The framework provides exact analytical expressions for key statistical properties of filament length distributions over time, such as the mean, variance, and Fano factor (a measure of dispersion) [3]. This allows researchers to distinguish between different potential regulatory mechanisms by comparing model predictions with experimental data from high-throughput microscopy, moving the field toward a predictive "theory of the experiment" [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA) with ATLAS Analysis

This protocol details the procedure for studying actomyosin interactions and analyzing data with the ATLAS software [6] [7].

Materials:

- Purified skeletal muscle or non-muscle myosin

- Fluorescently labeled phalloidin (e.g., Rhodamine-phalloidin)

- Purified rabbit skeletal muscle actin

- IVMA flow cells

- ATP-containing motility buffer

- Oxygen-scavenging system (e.g., glucose oxidase/catalase)

- TIRF or epifluorescence microscope with a CCD or sCMOS camera

- ATLAS software (open-source, platform-independent)

Procedure:

- Myosin Coating: Introduce a solution of myosin (~50-100 µg/mL) into the flow cell and incubate for 1 minute to allow adsorption to the glass surface. Block any remaining glass surface with a neutral protein like bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1 mg/mL).

- Fluorescent Actin Preparation: Pre-incubate G-actin with a 1.5-2x molar excess of fluorescent phalloidin for at least 30 minutes on ice to polymerize and label the actin filaments.

- Filament Introduction: Dilute the pre-formed, labeled F-actin in motility buffer and introduce it into the flow cell. Allow filaments to bind to the surface-bound myosin.

- Initiate Motility: Wash in motility buffer containing 2 mM ATP to initiate the myosin-powered gliding of actin filaments.

- Image Acquisition: Record videos of moving filaments for 60-120 seconds at a frame rate of 1-10 Hz using video fluorescence microscopy.

- ATLAS Analysis:

- Installation: Download and install ATLAS from its repository. Ensure MATLAB or the required runtime libraries are installed.

- Data Input: Load the acquired movie file into ATLAS.

- Filament Identification: The integrated machine learning model will automatically identify and segment fluorescent actin filaments in each frame.

- Motion Tracking: The software will track the centroids of the identified filaments across frames.

- Parameter Extraction: ATLAS will output the velocity (µm/s) and length (µm) for every tracked filament across the video.

- Data Export: Results can be exported for further statistical analysis and plotting.

Protocol: Quantifying Cortical Actin Meshwork with Super-Resolution Imaging

This workflow describes how to quantify the size of actin corrals from super-resolved images of the cell cortex, such as those obtained by SRRF or SIM [9].

Materials:

- Cultured cells (e.g., A549 cells)

- Phalloidin stain (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin)

- Paraformaldehyde fixative and permeabilization buffer

- Mounting medium

- Super-resolution microscope (e.g., for SRRF, 3D-SIM, or ExM)

- ImageJ/FIJI software with MorphoLibJ library

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Fix and permeabilize cells. Stain F-actin with fluorescent phalloidin. Mount slides.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire super-resolved images of the cortical actin meshwork just beneath the plasma membrane using SRRF, 3D-SIM, or a comparable method.

- Image Pre-processing (in FIJI): Crop a region of interest (ROI) of a standard size (e.g., 10 µm²) from a central area of the cell.

- Thresholding and Binarization: Manually threshold the image using Otsu's method to create a binary mask where filaments are white and corrals (pores) are black.

- Watershed Segmentation:

- Apply an erosion step (1-2 pixels) to the binary mask to better separate adjacent corrals.

- Run the classical watershed segmentation algorithm (available in the MorphoLibJ plugin) to partition the image into distinct, labeled corral regions.

- Particle Analysis:

- Use FIJI's "Analyze Particles" function on the watershed-segmented image.

- Set a size filter to exclude objects below the resolution limit of the microscope.

- The analysis will output quantitative descriptors for each corral, including Area and Perimeter.

- Validation and Interpretation: Compare corral areas between experimental conditions (e.g., control vs. cytochalasin D-treated cells). An increase in mean corral area indicates a disruption and opening of the actin meshwork [9].

Diagram 2: Workflow for Quantitative Analysis of Cortical Actin Mesh.

Actin Dynamics in a Specific Biological Context: T Cell Immunity

The critical importance of actin dynamics is vividly illustrated in the function of T lymphocytes, central players in adaptive immunity. Actin remodeling is essential for nearly every stage of the T cell life cycle, from development and migration to the execution of effector functions [4].

Upon recognition of antigen by the T cell receptor (TCR), a spectacular reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton occurs at the contact site with the antigen-presenting cell (APC), forming the immunological synapse (IS). Two key actin nucleators play complementary roles [4]:

- The Arp2/3 Complex: Activated by WASP, it generates a branched actin network at the synapse periphery. This network drives lamellipodial protrusion, facilitates TCR scanning, and helps cluster TCRs into central supramolecular activation clusters (cSMAC). Defects in this pathway, as in Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, lead to severe immunodeficiency [4].

- Formins (e.g., mDia1): Generate linear actin filaments that form concentric "actomyosin arcs" in the inner synapse. These arcs, powered by myosin II motor proteins, contract inward, corralling TCR microclusters toward the center and mechanically amplifying strong TCR signals—a key process in mechanotransduction [4].

This coordinated action of different actin nucleators and motors ensures efficient antigen recognition, stable cell-cell conjugation, and directed secretion of lytic granules, highlighting how precise spatiotemporal control of actin dynamics is paramount for effective immune surveillance and response.

Actin filament dynamics represent a cornerstone of eukaryotic cell biology. The force generated by controlled actin polymerization and myosin motor activity is harnessed for cellular motility, division, and internal organization. The development of advanced quantitative tools like ATLAS for high-throughput analysis and generalized theoretical models for multicomponent regulation is pushing the field toward a more comprehensive and predictive understanding of this complex system. As these tools are applied in diverse contexts—from fundamental biophysics to immunology and drug discovery—they will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into cellular mechanics and open new avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by cytoskeletal dysfunction.

The actin cytoskeleton is a dynamic filamentous network that assembles into specialized structures to enable cells to perform essential processes, including migration, growth, and division [11]. Quantitative analysis of actin filament architecture provides crucial insights into cellular physiological states and the mechanisms of actin-binding proteins (ABPs). The key metrics of filament length, number, and degree of bundling serve as sensitive biological indicators for research in cell biology, cytoskeletal dynamics, and drug development [11] [3].

Fluorescence microscopy of labeled cytoskeletal proteins has revolutionized our understanding of actin dynamics, though accurate quantification remains challenging due to the interdependent and kinetic nature of the reactions involved [11]. This Application Note details standardized protocols and computational frameworks for extracting quantitative data on these key metrics, enabling researchers to translate fluorescence micrographs into statistically robust, quantitative measurements of actin organization.

Computational Tools for Filament Quantification

Several sophisticated computational tools have been developed to automate the quantification of actin filaments from fluorescence images, enhancing throughput, accuracy, and reproducibility. The table below summarizes key available frameworks.

Table 1: Computational Tools for Actin Filament Analysis

| Tool Name | Programming Language/Platform | Primary Functions | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Custom MATLAB Programs [11] | MATLAB | Filament counting, length measurement, bundling quantification | Interactive error correction; adjustable thresholds; suitable for equilibrium and kinetic studies |

| Robust Actin Framework [12] | Not Specified | Filament orientation, position, and length extraction | High sensitivity in noisy/blurry images; multi-scale line detection |

| ATLAS [6] | Platform-independent machine learning | Filament length and velocity tracking in motility assays | High-throughput analysis; reduced human bias; trained on simulated and experimental data |

| SOA.2.0 [13] | Python with Tkinter GUI | Segmentation and orientation analysis of branch-like structures | Accessible GUI; no programming expertise required; analyzes parallel growth |

Workflow for Filament Length and Number Quantification

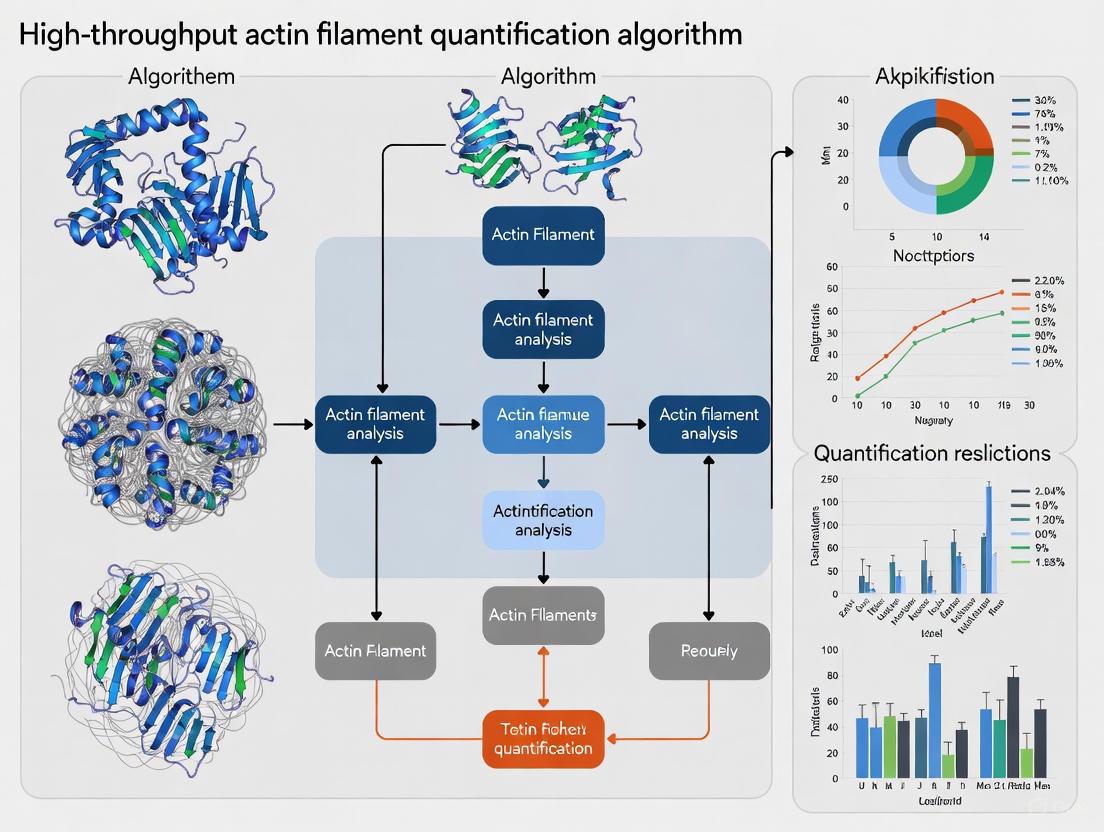

The general workflow for quantifying filament length and number, as implemented in the MATLAB-based program [11], involves a multi-step image processing pipeline. The following diagram illustrates the sequence of operations from raw image acquisition to final data output.

Figure 1. Image Analysis Workflow for Filament Quantification. The process involves automated steps (blue/green) and a critical manual error-correction step (green) to ensure accuracy, particularly for overlapping filaments.

Critical Step: Manual Error Correction

A critical finding from methodology development is the necessity of manual error correction. A comparative analysis demonstrated that fully automated methods introduce significant bias [11]. Automatically removing overlapping filaments yielded shorter average lengths, while failing to correct errors produced longer and more variable measurements. The manual resolution step, where users interactively separate overlapping filaments via a graphical interface, was shown to significantly increase measurement accuracy (P<0.01) [11].

Quantification of Filament Bundling

Bundling as a Kinetic Metric

Actin filaments are crosslinked into larger structures by bundling proteins, which bind two filaments simultaneously. This bundling process is dynamic, with progression rates dependent on the concentration of bundling proteins and filament length [11]. In fluorescence microscopy, bundling manifests as a localized increase in fluorescence intensity along the lengths of labeled actin filaments, as multiple filaments come into close apposition [11].

Theoretical Framework for Multicomponent Regulation

The regulation of actin filament dynamics, including bundling, often involves the concerted action of multiple ABPs. A recent generalized theoretical framework provides a powerful tool for interpreting filament length distribution data in complex systems [3]. This kinetic model incorporates the combined effects of an arbitrary number of regulatory proteins (e.g., elongators like formins, cappers, and depolymerizers) and derives exact mathematical expressions for statistical properties like the mean and variance of filament length changes over time. This allows researchers to distinguish between different potential regulatory mechanisms based on experimental data [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of this theoretical framework, where a filament stochastically transitions between different states of activity governed by ABPs.

Figure 2. State-Transition Model for Filament Dynamics. Filaments stochastically transition between states (e.g., polymerizing, capped, depolymerizing) with specific rate constants (kᵢⱼ). The combined effect of all states determines the net change in filament length [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Quantifying Filament Length and Number at Equilibrium

This protocol is adapted from assays used to validate the MATLAB quantification tool, analyzing pre-assembled actin filaments under equilibrium conditions [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Actin Polymerization Assays

| Reagent | Function | Example Formulation/Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Actin Monomers | Core polymerizing unit | 2 µM G-actin in polymerization buffer [11] |

| Polymerization Buffer | Provides ionic conditions for polymerization | Contains 75 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM ATP, 25 mM imidazole hydrochloride (pH 7.4) [11] [14] |

| Fluorescent Phalloidin | Stabilizes and labels F-actin for visualization | e.g., FITC- or Rhodamine-phalloidin [11] [15] |

| Anti-bleach Mixture | Reduces photobleaching during imaging | 3 mg/ml glucose, 20 units/ml glucose oxidase, 920 units/ml catalase [14] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation:

- Incubate 2 µM purified actin monomers in polymerization buffer at room temperature for 2 hours to allow spontaneous nucleation and elongation, reaching steady-state equilibrium [11].

- Stabilize and label the filaments by adding fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC) phalloidin.

- Microscopy:

- Immobilize a sample of the reaction on a glass coverslip for visualization. This can be done by directly applying the solution to the surface or using a flow chamber [11].

- Acquire fluorescence micrographs using TIRF or confocal microscopy. For robust analysis, acquire multiple images from different fields of view [11] [15].

- Image Analysis:

- Process images using the computational workflow detailed in Figure 1.

- Input the micrograph(s) into the analysis program (e.g., the described MATLAB tool).

- Set parameters for background subtraction (using a 2D Gaussian filter) and intensity thresholding for binarization.

- Execute the skeletonization algorithm and run automated error detection.

- Manually resolve all detected errors (overlapping filaments/crossovers) via the interactive interface.

- Run the final quantification to obtain filament counts and length measurements, exported for downstream statistical analysis.

Protocol B: Kinetic Measurement of Filament Bundling

This protocol outlines how to quantify the kinetics of an actin filament bundling reaction in real-time [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Pre-formed Actin Filaments: Prepare stable, fluorescently labeled filaments as described in Protocol A.

- Bundling/Crosslinking Protein: The protein of interest (e.g., fascin, α-actinin) at the desired concentration [11].

- Assay Buffer: An appropriate buffer that maintains the activity of the bundling protein, potentially including the anti-bleach mixture for time-lapse imaging.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Reaction Setup and Imaging:

- Introduce the bundling protein to the solution containing immobilized, fluorescently labeled actin filaments. This can be done in a flow chamber to initiate the reaction [11].

- Immediately begin time-lapse fluorescence microscopy, capturing images of the same field of view at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) as the bundling reaction progresses.

- Image Analysis:

- Process the time-series stack of micrographs using a dedicated bundling quantification program [11].

- The program uses fluorescence intensity along the filaments as a readout for bundling. As filaments bundle, the local fluorescence signal increases.

- The output is a kinetic trace of the bundling reaction, quantifying the increase in fluorescence intensity (representing the degree of bundling) over time until equilibrium is reached.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below consolidates key resources for researchers designing experiments in actin filament quantification.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Filament Analysis

| Category | Tool / Reagent | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | MATLAB-based Programs [11] | Quantifying filament number, length, and bundling from static or time-lapse images |

| ATLAS [6] | High-throughput, machine learning-based tracking of filament length and velocity in motility assays | |

| SOA.2.0 [13] | Automated segmentation and analysis of parallel growth in branch-like structures | |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Generalized Kinetic Model [3] | Interpreting filament length distribution data under multi-protein regulation |

| Key Reagents | Fluorescent Phalloidin | F-actin stabilization and labeling for fluorescence microscopy |

| Anti-bleach Mixture [14] | Prolonging fluorescence signal integrity during time-lapse imaging | |

| Experimental Assays | In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA) | Studying actin-myosin interactions and motor protein activity [6] |

| Surface Immobilization | Anchoring filaments for consistent visualization by TIRF microscopy [11] |

Actin filaments form intricate and dynamic networks that are fundamental to cell structure, motility, and division. For researchers and drug development professionals, quantitative analysis of these networks offers valuable insights into cellular mechanics and the effects of pharmaceutical compounds. However, extracting meaningful quantitative data from actin images presents significant challenges, primarily due to high network density, low signal-to-noise ratios, and structural variability across cellular contexts.

This application note addresses these impediments by presenting and benchmarking advanced computational tools designed for specific actin imaging scenarios. We provide a structured comparison of available algorithms, detailed experimental protocols for their application, and a catalog of essential reagents to facilitate robust, high-throughput actin filament quantification.

Algorithm Comparison and Selection Guide

The choice of quantification algorithm depends critically on the imaging modality, the specific actin structure of interest, and the biological question. The table below summarizes the capabilities of four specialized tools in addressing core imaging challenges.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Actin Filament Analysis Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Primary Imaging Modality | Best Suited Actin Structure | Key Strength | Reported Performance/Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BundleTrac [16] | Cryo-Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET) | Dense actin bundles (e.g., hair cell stereocilia) | Semi-automatic tracing in high-noise, anisotropic volumes | 98.8% filament detection rate (326 of 330 filaments) [16] |

| ATLAS [7] [6] | Fluorescence Video Microscopy (IVMA) | Motile actin filaments in vitro | Machine learning-enhanced tracking of filament motion and length | Accurate velocity/length measurement across broad experimental conditions [7] |

| 4polar-STORM [17] | Polarized Super-Resolution (STORM) | Dense actin organizations in cells (e.g., stress fibers, lamellipodia) | Determines single filaments' orientation and wobbling in 2D/3D | Compatible with high single-molecule densities (>1 molecule/μm²) [17] |

| SFEX [18] | Fluorescence Microscopy (TIRF) | Actin stress fibers in adherent cells | Automated network extraction and reconstruction from complex backgrounds | Enables comprehensive trajectory extraction of majority of fibers [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tracing Actin Bundles in Cryo-ET Data with BundleTrac

This protocol is designed for analyzing dense actin bundles from cryo-electron tomography data, such as those in hair cell stereocilia, where traditional filament tracing fails due to molecular crowding and noise [16].

Materials and Reagents

- Reconstructed Cryo-ET Density Map: Data acquired from native tissue or cellular contexts.

- BundleTrac Software: Available as described in Molecules. 2018;23(4):882.

- Workstation: With sufficient memory for processing large 3D volumetric data.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preparation: Load the reconstructed 3D density map of the actin bundle into the BundleTrac software environment.

- Seed Point Initialization: For each filament to be traced, manually provide a single seed point within the density map. This initial user input guides the subsequent automated tracing.

- Automated Filament Identification: Run the BundleTrac algorithm. The software will computationally identify the path of each filament through the 3D volume based on the provided seed points.

- Model Validation and Refinement: Compare the computationally built filaments against manual traces. The reported overall cross-distance for 330 filaments was 1.3 voxels, providing a benchmark for accuracy [16].

- Denoising (Optional): Apply the integrated polynomial regression denoising method to enhance the density map and improve trace clarity in high-noise conditions.

Protocol 2: High-Content Actin Filament Tracking with ATLAS

This protocol uses the ATLAS software for the automated, high-throughput analysis of actin filament motion and length in the In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA), eliminating slow and biased manual video analysis [7] [6].

Materials and Reagents

- IVMA Sample: Myosin-coated glass surface propelling fluorescently labeled actin filaments.

- Recording System: Video fluorescence microscope.

- ATLAS Software: Open-source, platform-independent package.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Video Acquisition: Record the motion of fluorescently labeled actin filaments propelled by surface-bound myosin using standard video fluorescence microscopy.

- Data Input and Preprocessing: Import the video file into ATLAS. The software will preprocess the data to optimize it for machine learning analysis.

- Machine Learning-Based Identification and Tracking: Execute the main ATLAS module. The built-in state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms will:

- Identify the fluorescent actin filaments in each frame.

- Track their movement across consecutive frames.

- Parameter Extraction: Allow ATLAS to automatically calculate key parameters, including filament velocity and length, for all tracked filaments across the video.

- Data Export: Export the results for further statistical analysis and visualization.

Protocol 3: Nanoscale Orientation Mapping with 4polar-STORM

This protocol details the use of 4polar-STORM to achieve super-resolution imaging of actin filament organization while simultaneously obtaining information on single filament orientation and conformation in dense cellular environments [17].

Materials and Reagents

- Fixed Cell Sample: Cells stained with actin-binding fluorophores (e.g., phalloidin conjugates) compatible with STORM imaging.

- Microscope Setup: Equipped for STORM and polarization splitting. The detection numerical aperture (NA) must be adjustable; set to 1.2 for this protocol.

- 4-Way Polarization Splitting Optics: To project the image onto four channels (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation and Mounting: Prepare and mount the fixed, stained cell sample on the microscope stage.

- Microscope Configuration: Reduce the detection NA to 1.2. This critical step minimizes bias in orientation measurements and decouples them from the distance to the coverslip interface [17].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire single-molecule localization data simultaneously in the four polarization channels.

- Ratiometric Analysis: For each localized single molecule, calculate the ratiometric factors:

- ( P0 = (I0 - I{90}) / (I0 + I_{90}) )

- ( P{45} = (I{45} - I{135}) / (I{45} + I{135}) ) where ( Iθ ) is the integrated intensity in the channel with polarization angle θ [17].

- Parameter Retrieval: Determine the fluorophore's mean 2D orientation (ρ) and wobbling (δ) from the (P₀, P₄₅) values. Use these measurements to infer the 3D organizational state of the actin filaments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in sample preparation for advanced actin imaging.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Actin Network Imaging and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phalloidin (Fluorescent conjugate) | Binds and stabilizes F-actin, allowing visualization. | Standard fluorescence microscopy (e.g., TIRF) and super-resolution (dSTORM) [19] [18]. |

| XIRP2 (Antibody or recombinant) | Mechanosensitive protein used as a marker for actin damage/repair sites. | Investigating actin core repair in stereocilia after noise-induced damage [20]. |

| FLEx-β-actin-EGFP Mouse Model | Enables pulse-chase labeling of newly synthesized actin. | Tracking incorporation of new actin into repairing stereocilia cores [20]. |

| Matrigel | Extracellular matrix coating to support cell adhesion and spreading. | Cell culture for stress fiber analysis and myogenic differentiation studies [21]. |

| Cellular Media (Serum-free formulations) | Supports specific cell states like proliferation or differentiation without serum interference. | High-throughput label-free quantification of myogenic differentiation [21]. |

The imaging challenges posed by actin networks—density, noise, and variability—are no longer insurmountable barriers to high-throughput, quantitative research. By matching the specific biological context and imaging modality with the appropriate computational tool, such as BundleTrac for cryo-ET, ATLAS for dynamic IVMA studies, or 4polar-STORM for nanoscale structural organization, researchers can extract robust, quantitative data. The protocols and reagents detailed herein provide a foundational roadmap for implementing these advanced analyses, thereby accelerating discovery in basic cell biology and drug development.

The actin cytoskeleton is a fundamental component of eukaryotic cells, governing essential processes including cell division, migration, adhesion, and intracellular transport. Quantitative analysis of actin filaments has emerged as a critical methodology for translating microscopic observations of actin organization into robust, statistically significant data. Recent advances in machine learning algorithms and high-throughput imaging have revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to move from qualitative descriptions to precise measurements of actin dynamics across various experimental contexts. These technological developments have established a direct pipeline from basic cytoskeletal research to applied drug discovery, particularly in areas where actin remodeling plays a pathogenic role.

This application note details established protocols and analytical frameworks for quantifying actin structures, focusing on reproducible methods that generate quantitative data suitable for statistical analysis and high-content screening. We emphasize approaches that have been validated across multiple model systems and demonstrate direct relevance to drug development workflows.

Actin Analysis in Basic Research

Automated Filament Tracking with ATLAS

The In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA) is a established experimental system for studying the chemomechanical activity of myosin and other cytoskeletal motor proteins. In a typical IVMA, myosin molecules are bound to a glass surface and propel fluorescently labeled actin filaments, with their motion recorded via video fluorescence microscopy. The length and velocity of these actin filaments provide crucial measurements of motor protein activity [7] [6].

The Automated Tracking of Learned Actin Structures (ATLAS) software package addresses a critical bottleneck in IVMA analysis by replacing slow, labor-intensive manual tracking with an automated, machine learning-enhanced workflow. As an open-source, platform-independent solution, ATLAS utilizes state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms to identify fluorescently labeled actin filaments and track their motion with minimal human bias [7]. The software has been validated using both experimental data and simulated actomyosin motility movies, demonstrating accurate measurement of actin filament velocity and length across diverse experimental conditions [6].

Table 1: Key Outputs from ATLAS Software for Actin Filament Analysis

| Quantitative Output | Biological Significance | Applications in Basic Research |

|---|---|---|

| Filament Velocity | Measures motor protein force generation | Kinetics of myosin-actin interactions |

| Filament Length | Indicates polymerization/depolymerization rates | Actin dynamics under various nucleotide conditions |

| Trajectory Analysis | Reveals directionality and processivity | Mechanistic studies of motor protein function |

| Population Statistics | Provides ensemble behavior across many filaments | Statistical comparison of experimental conditions |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Motility Assay with ATLAS Analysis

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified actin protein (≥95% pure, preferably muscle actin)

- Fluorescent phalloidin (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, Rhodamine, or Cy3 conjugate)

- Purified motor proteins (myosins, kinesins, or dyneins)

- ATP regeneration system (creatine phosphate and creatine kinase)

- Flow chambers constructed from nitrocellulose-coated glass slides and coverslips

- IVMA buffer: 25 mM imidazole, 25 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4

Methods:

- Actin Labeling: Incubate G-actin with a 1.5-fold molar excess of fluorescent phalloidin for 30 minutes at room temperature, then polymerize by adding 1 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM KCl for 1 hour.

- Flow Chamber Preparation: Adsorb motor proteins (50-100 μg/mL) to nitrocellulose-coated coverslips for 5 minutes, then block with 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin for 2 minutes.

- Assay Assembly: Introduce fluorescent actin filaments (1-5 nM) in IVMA buffer containing 2 mM ATP and an ATP-regeneration system into the flow chamber.

- Image Acquisition: Record filament movement using TIRF or epifluorescence microscopy at 1-5 frames per second for 2-5 minutes.

- ATLAS Analysis:

- Import video files into ATLAS software

- Select processing parameters (default recommended for initial use)

- Run automated filament identification and tracking algorithm

- Export velocity and length measurements for statistical analysis

Technical Notes: Optimal results require minimal photobleaching; consider oxygen-scavenging systems for prolonged imaging. For drug testing applications, include compounds in the final assay buffer.

Theoretical Frameworks for Actin Dynamics Interpretation

Interpreting quantitative actin data requires robust theoretical models. A recent generalized kinetic framework enables researchers to extract mechanistic information from filament length distributions obtained through experiments like IVMA. This model incorporates the combined effects of multiple actin-binding proteins (ABPs) on actin dynamics, providing exact closed-form expressions for statistical moments of filament length distributions [3].

The model conceptualizes filaments transitioning between discrete states representing different combinations of bound ABPs, with each state associated with specific polymerization or depolymerization rates. This approach allows researchers to distinguish between different regulatory mechanisms by analyzing mean filament length changes and Fano factors (variance-to-mean ratios) calculated from experimental data [3].

Diagram 1: Theoretical framework for analyzing multi-component actin regulation. This workflow enables researchers to infer regulatory mechanisms from filament length distribution data.

Advanced Methodologies for Live-Cell and High-Content Analysis

Genetically Encoded Reporters for Live-Cell Polarimetry

Traditional actin probes like phalloidin conjugates are unsuitable for live-cell applications due to their toxicity and cell impermeability. Recent breakthroughs have resulted in genetically encoded reporters that enable measurements of actin filament organization in living cells and tissues through fluorescence polarization microscopy (polarimetry) [22].

These engineered reporters consist of GFP fusions to actin-binding domains with constrained mobility, enabling them to report on actin filament orientation and alignment. When combined with polarimetry, which exploits the sensitivity of polarized light to fluorophore orientation, these tools provide unprecedented information about the molecular-scale organization of actin filaments in living systems [22].

Polarimetry measurements yield two key parameters per image pixel:

- Angle ρ (rho): Represents the mean orientation of fluorophores (and thus actin filaments) within the focal volume

- Angle ψ (psi): Indicates the in-plane projection of the angle explored by fluorophores, with lower values indicating higher filament alignment

Experimental Protocol: Live-Cell Actin Organization Analysis

Materials and Reagents:

- Genetically encoded actin organization reporters (e.g., constrained GFP-ABD fusions)

- Suitable cell line (U-2 OS, HeLa, or other adherent mammalian cells)

- Polarization microscopy system with controlled excitation polarization

- Standard cell culture materials and reagents

Methods:

- Cell Preparation: Transfect cells with plasmid DNA encoding the actin organization reporter using standard transfection protocols.

- Image Acquisition: 48-72 hours post-transfection, acquire polarization-resolved images using a system capable of rotating the excitation polarization.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate orientation (ρ) and organization (ψ) maps from polarization image series

- Segment cells and cellular regions of interest (e.g., stress fibers, cortical actin)

- Extract statistical distributions of ρ and ψ values for quantitative comparisons

- Compare experimental ψ values with reference values from known structures (e.g., stress fibers: ψ = 15-25°)

Technical Notes: Optimal expression levels are critical; avoid overexpression that disrupts native actin structures. Include control cells expressing unconstrained GFP fusions to establish baseline organization measurements.

Self-Supervised Learning for High-Content Actin Analysis

Traditional machine learning approaches for image analysis require large, annotated datasets, creating a significant bottleneck for high-content applications. Self-supervised learning (SSL) methodologies overcome this limitation by training directly on the user's data without manual annotation [23].

This SSL approach for pixel classification works by applying a Gaussian filter to create a blurred version of the original image, then calculating optical flow vectors between the original and blurred image. These vectors serve as the basis for self-labeling pixel classes ("cell" vs "background") to train an image-specific classifier in a completely automated fashion [23].

The algorithm has demonstrated versatility across:

- Multiple microscopy modalities: Phase contrast, brightfield, DIC, and fluorescence

- Various magnifications: From 10X to 63X objectives

- Diverse cell types: Mammalian cells, fungi, and other model systems

- Complex structures: F-actin, vinculin, and other cytoskeletal components

Table 2: Comparison of Actin Analysis Methods for Drug Discovery Applications

| Method | Throughput | Live-Cell Capability | Information Content | Best Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATLAS-IVMA | Medium | No (fixed endpoint) | Filament dynamics & motor function | Target validation for motor protein inhibitors |

| Live-Cell Polarimetry | Low to Medium | Yes | Filament organization & alignment | Mechanistic studies of cytoskeletal-targeting drugs |

| SSL Segmentation | High | Yes (compatible with live imaging) | Cellular morphology & structure | High-content screening of compound libraries |

| Kinetic Modeling | N/A (analytical) | N/A (analytical) | Regulatory mechanism inference | Interpretation of screening results & mechanism identification |

Diagram 2: Self-supervised learning workflow for automated actin segmentation. This approach eliminates the need for manually annotated training data by generating labels directly from image features.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

High-Throughput Screening of Cytoskeletal-Targeting Compounds

Quantitative actin analysis enables targeted drug discovery for conditions where cytoskeletal dysfunction plays a central role. High-throughput, label-free imaging approaches now allow continuous monitoring of muscle stem cell proliferation and differentiation, processes fundamentally dependent on actin remodeling [21].

This methodology employs high-contrast brightfield (HCBF) imaging optimized for automated imaging systems, enabling kinetic profiling of myotube formation in standard 96- and 384-well formats without fluorescent labeling or cell fixation. The approach reveals subtle phenotypic changes in response to compound treatment, including alterations in differentiation kinetics, myotube morphology, and contractile behavior [21].

For actin-targeting compounds specifically, this platform can quantify:

- Changes in actin-dependent cellular structures

- Alterations in differentiation kinetics

- Myotube morphology variations

- Effects on cytoskeletal organization

Actin-Based Toxicity Assessment

Many drug candidates fail in development due to unexpected cytoskeletal toxicity. Quantitative actin analysis provides a sensitive method for detecting such liabilities early in the drug discovery pipeline. By applying the high-content methodologies described previously, researchers can simultaneously assess both efficacy and cytoskeletal toxicity in the same screening campaign.

The SSL segmentation approach [23] is particularly valuable here, as it can identify subtle alterations in actin organization that might be missed by traditional toxicity assays. This includes changes in:

- Stress fiber organization

- Cortical actin integrity

- Filopodial and lamellipodial dynamics

- Cell adhesion complexity

Experimental Protocol: Compound Screening Using Actin Morphology

Materials and Reagents:

- 384-well tissue culture plates

- Cells expressing actin reporter (GFP-ABD or similar)

- Compound library for screening

- High-content imaging system with environmental control

- Fixation and staining reagents (if fixed endpoint required)

Methods:

- Cell Plating: Plate reporter cells in 384-well plates at optimized density and culture for 24 hours.

- Compound Treatment: Add compounds using automated liquid handling, including appropriate controls.

- Image Acquisition: At designated timepoints (e.g., 6, 24, 48 hours), acquire images using automated microscopy.

- Image Analysis:

- Apply SSL segmentation to identify cells and subcellular compartments

- Quantify actin organization parameters (alignment, intensity, distribution)

- Measure cell morphological features (size, shape, spreading)

- Calculate compound-induced changes relative to controls

- Hit Identification: Select compounds based on efficacy and absence of cytoskeletal toxicity.

Technical Notes: Include reference compounds with known effects on actin cytoskeleton as controls. For live-cell imaging, maintain temperature and CO₂ control throughout experiment.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative Actin Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Phalloidin | F-actin staining by binding along filaments | Fixed-cell imaging, IVMA | High specificity, various fluorophore options |

| Genetically Encoded Actin Reporters (GFP-ABD) | Live-cell actin visualization | Polarimetry, dynamics studies | Genetically encoded, suitable for long-term imaging |

| SiR-Jasplakinolide | F-actin staining, membrane permeable | Live-cell imaging (limited use) | Cell permeability, far-red fluorescence |

| - Constrained GFP-Actin Reporters | Live-cell organization measurements | Polarimetry studies | Reduced mobility enables orientation measurements |

| ATLAS Software | Automated filament tracking and analysis | IVMA data analysis | Machine learning-based, open-source platform |

| Self-Supervised Learning Algorithm | Automated image segmentation | High-content screening | No training data required, adaptable to new conditions |

Diagram 3: Drug discovery pipeline enhanced by quantitative actin analysis. Each stage benefits from specific actin quantification methodologies, from basic research to preclinical development.

Quantitative actin analysis has evolved from a basic research tool to an essential component of modern drug discovery pipelines. The methodologies outlined in this application note—from automated filament tracking and theoretical modeling to live-cell polarimetry and self-supervised learning—provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating actin biology in health and disease. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics targeting cytoskeletal pathologies while improving the safety profile of drug candidates across therapeutic areas.

By adopting these standardized protocols and analytical frameworks, research teams can generate comparable, reproducible data across laboratories, facilitating collaboration between basic researchers and drug discovery scientists. The integration of these quantitative approaches throughout the drug development pipeline represents a significant advancement in our ability to target cytoskeletal mechanisms with precision and confidence.

Implementing Advanced Algorithms: From CNN Segmentation to Automated Workflows

The quantitative analysis of filamentous structures, particularly actin filaments, is fundamental to understanding critical cellular processes such as proliferation, migration, and division [24]. Actin filaments are highly dynamic components of the cytoskeleton that undergo continuous reorganization, and their morphological characteristics—including length, abundance, and organizational class—provide crucial metrics for studying cell mechanics and drug responses [24] [8]. However, traditional image analysis methods face significant challenges in accurately segmenting these structures due to the dense, complex architecture of filament networks, high noise levels in microscopic images, and the presence of overlapping and intersecting filaments [24] [25].

Deep learning approaches, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have emerged as powerful tools for overcoming these challenges. These methods enable precise segmentation and instance-level extraction of filaments from both fluorescence microscopy and electron tomography data, facilitating high-throughput quantitative analysis that was previously impeded by labor-intensive manual annotation [26] [27]. This Application Note details current CNN-based methodologies, protocols, and reagents for filament segmentation, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these approaches in actin filament quantification research.

Key Methodologies and Quantitative Comparisons

Several specialized CNN architectures have been developed to address the unique challenges of filament segmentation. The U-Net architecture, with its encoder-decoder structure and skip connections, has proven particularly effective for semantic segmentation of filamentous structures [28] [29]. For more complex instance segmentation tasks, where individual filaments must be distinguished within dense networks, advanced architectures like orientation-aware networks and keypoint detection approaches have demonstrated superior performance [24] [25].

Orientation-aware networks incorporate multiple branches, each dedicated to detecting filaments within specific orientation ranges, effectively transforming complex intersections into more manageable "overpass" structures [25]. Alternatively, keypoint detection methods adapted from human pose estimation techniques can precisely identify filament junctions and endpoints, which are then processed using fast marching algorithms to quantify filament length and abundance [24]. The following table summarizes the primary CNN architectures currently employed in filament segmentation:

Table 1: Deep Learning Approaches for Filament Segmentation

| Method Name | Architecture Type | Key Innovation | Best Application Context | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keypoint Detection + Fast Marching [24] | Modified ResNet-101 | Adapts human pose estimation for junction/endpoint detection | Dense actin networks in microscopic images | Outperforms existing methods in accuracy and inference time |

| Orientation-Aware Network [25] | Multi-branch U-Net variant | Six orientation-specific branches separate filaments at junctions | Complex filament networks with frequent crossings | Remarkable performance on microtubule and road datasets |

| U-Net with Post-processing [28] | Standard U-Net | Achieves high pixel-level accuracy with optimized hyperparameters | Zebrafish epidermal microridges | ~95% pixel-level accuracy; effective persistence length estimation |

| FAST [8] | Deep Learning (unspecified) | Segments and quantifies different classes of actin structures | Phalloidin-stained confocal images of various actin classes | Enables quantification without specific antibodies |

| TARDIS [26] | FNet with DIST transformer | Geometry-aware instance segmentation on point clouds | Cryo-electron tomograms of membranes and filaments | 42% accuracy improvement for microtubules; processes tomograms in minutes |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

When selecting a segmentation approach for high-throughput research, understanding computational performance and accuracy trade-offs is essential. The following table synthesizes quantitative performance metrics reported across multiple studies:

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Segmentation Methods

| Method | Segmentation Accuracy | Inference Speed | Filament Length Quantification | Instance Segmentation Capability | Required Training Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keypoint Detection [24] | Superior to comparison methods | Fast | Excellent via fast marching algorithm | Yes through keypoints | Synthetic junction dataset |

| Orientation-Aware Network [25] | Outperforms most existing approaches | Not specified | Enabled through terminus pairing | Yes through orientation separation | Synthetic filaments + real annotated data |

| U-Net Framework [28] | ~95% pixel accuracy | ~1 minute per cell | Enables persistence length calculation (~6.1 μm) | No (semantic segmentation) | 93% of dataset (MBS=6, ME=800) |

| TARDIS [26] | 42% improvement for microtubules vs. existing tools | Minutes per tomogram (vs. months manually) | Enabled through instance identification | Yes via DIST transformer | Largest annotated dataset to date (71,747 objects) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Actin Filament Quantification Using Keypoint Detection and Fast Marching

This protocol enables accurate quantification of actin filament length and abundance in microscopic images through a combination of CNNs and fast marching algorithms [24].

Materials and Equipment

- Microscopy Images: 2D maximum intensity projection (MIP) images of actin filaments (e.g., 1740 × 840 pixels)

- Computing Hardware: GPU-enabled workstation (minimum 8GB VRAM recommended)

- Software Dependencies: Python 3.7+, PyTorch or TensorFlow, scikit-fmm [24]

Procedure

Binary Segmentation of Actin Filaments:

Junction and Endpoint Detection:

- Modify a ResNet-101 architecture for keypoint detection [24].

- Generate synthetic training data by creating 10,000 images (128 × 128 pixels) with random one-pixel width curves, then dilating with kernels of size 3-7 to resemble segmented filaments [24].

- Train the network using a combined loss function (Dice-coefficient for heatmaps, L1 loss for offset maps) [24].

- Apply the trained model to binary segmentation results to detect junctions and endpoints through Hough voting.

Filament Quantification with Fast Marching:

- Initialize contours around detected keypoints (junctions and endpoints).

- Apply the fast marching algorithm from scikit-fmm to compute geodesic distance maps [24].

- Identify local peak values in the distance map, which correspond to filament midpoints.

- Calculate filament length by doubling peak values (representing half-lengths).

- Quantify filament abundance by counting the number of peaks.

Troubleshooting

- Poor Junction Detection: Increase diversity in synthetic training data by including more junction types and varying filament curvature.

- Inaccurate Length Measurement: Verify binary segmentation quality and adjust fast marching parameters.

- Overlapping Filaments: Implement post-processing to resolve ambiguities in dense regions.

Protocol 2: Instance Segmentation of Filaments Using Orientation-Aware CNN

This protocol addresses the challenge of segmenting individual filaments in complex networks by separating filaments based on orientation [25].

Materials and Equipment

- Image Data: Fluorescence microscopy images of filamentous structures (microtubules or actin)

- Computing Hardware: GPU with sufficient memory for multi-branch network

- Software Dependencies: Deep learning framework with U-Net implementation

Procedure

Network Implementation:

- Implement a U-Net architecture with six parallel hourglass modules [25].

- Configure each branch for specific orientation ranges: [0°, 30°), [30°, 60°), [60°, 90°), [90°, 120°), [120°, 150°), [150°, 180°).

- Include two output paths: (1) merged reconstruction of all orientations, (2) separation loss to minimize overlap between orientation outputs.

Training Procedure:

- Create training data with orientation-associated ground truth maps.

- Use a combined loss function that includes reconstruction accuracy and separation constraints.

- Train for sufficient epochs until orientation separation is consistent.

Terminus Pairing and Filament Extraction:

- Process test images through the trained network to obtain orientation-separated fragments.

- Implement terminus pairing algorithm to connect fragments across orientation branches based on location and propagation vectors.

- Extract complete filaments by regrouping connected fragments.

Troubleshooting

- Over-fragmentation of Curved Filaments: Adjust orientation range granularity or increase curvature examples in training data.

- Incorrect Terminus Pairing: Optimize pairing parameters based on distance and directional consistency.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Filament Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net Architecture [28] | Semantic segmentation of filament structures | Pixel-level accuracy in microridge segmentation | Optimize hyperparameters: image size=256², learning rate=10⁻⁴, MBS=6, ME=800 |

| ResNet-101 (Modified) [24] | Junction and endpoint detection in filament networks | Keypoint detection for actin filament quantification | Train with synthetic data; use Dice and L1 loss functions |

| Orientation-Aware CNN [25] | Instance segmentation by orientation separation | Microtubule network analysis with complex junctions | Six orientation branches (30° intervals); requires terminus pairing algorithm |

| Fast Marching Algorithm [24] | Geodesic distance computation for length measurement | Actin filament length quantification from keypoints | Implement using scikit-fmm; local peaks indicate filament midpoints |

| TARDIS Framework [26] | Automated instance segmentation in electron tomograms | Membrane and filament segmentation in cryo-ET data | Uses FNet for semantic segmentation + DIST for instance identification |

| DeePiCt [29] | Supervised segmentation and particle localization | Ribosome and filament identification in cellular context | Combines 2D CNN (compartments) + 3D CNN (particles/continuous structures) |

| Synthetic Data Generation [24] [25] | Training data creation when annotated data is limited | Junction detection and orientation-aware segmentation | Create random curves with varying junctions; apply dilation to simulate thickness |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Cryo-Electron Tomography Integration

CNN-based filament segmentation has been successfully extended to cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET), enabling molecular-level structural analysis. The DeePiCt framework synergizes 2D CNNs for segmenting cellular compartments with 3D CNNs for localizing particles and annotating continuous structures like filaments [29]. This approach benefits from the contextual information between filaments and associated macromolecular complexes, improving segmentation accuracy in crowded cellular environments. Similarly, the TARDIS framework provides automated segmentation of filaments and membranes in cryo-ET data, reducing annotation time from months to minutes while improving accuracy by 42% for microtubules compared to existing tools [26].

Multi-Scale Actin Structure Analysis

The FAST (Filamentous Actin Segmentation Tool) platform demonstrates how deep learning can discriminate between different organizational classes of actin structures—from single filaments to bundled networks—in phalloidin-stained confocal images [8]. This capability is particularly valuable for drug development research, where quantifying changes in actin organization in response to therapeutic compounds provides insights into mechanisms affecting cell motility and cancer metastasis. By training CNNs on lifeact-GFP movies during drug treatments, researchers can dynamically track actin reorganization, enabling high-throughput screening of compounds targeting the cytoskeleton.

Workflow for High-Throughput Analysis

For high-throughput applications such as drug development, establishing automated workflows is essential. The integration of CNN-based segmentation with downstream analysis enables comprehensive characterization of actin filament properties across multiple experimental conditions. These pipelines can process hundreds of images automatically, extracting quantitative descriptors of filament morphology and dynamics that correlate with cellular phenotypes and drug responses [6] [8]. The protocols outlined in this document provide the foundation for implementing such high-throughput systems in research and drug discovery environments.

The quantification of actin filaments is fundamental to research in cell biology, drug development, and the study of cytoskeletal dynamics. Key metrics such as filament length and count provide crucial insights into cellular mechanics and responses to stimuli [30]. Traditional methods for quantifying these features from microscopic images are often hampered by noise, complex dense networks, and manual biases, limiting their throughput and accuracy [6] [30]. This document outlines a deep learning-based framework that repurposes and modifies ResNet architectures for the precise detection of junctions and endpoints in actin filament networks. This approach enables high-throughput, automated quantification, representing a significant advancement for research and pharmaceutical screening [30].

Theoretical Background

Actin filaments form dense, highly dynamic networks within eukaryotic cells. Accurate quantification of these structures requires instance-level segmentation to disentangle individual filaments from a complex web. Traditional computer vision techniques, such as global thresholding and skeletonization, often fail in dense regions and are sensitive to image noise, leading to inaccurate filament tracing and length miscalculations [30].

Inspired by advances in human pose estimation, this method treats the actin network as a skeletal structure. The junctions (where filaments cross) and endpoints (where filaments terminate) are conceptualized as "keypoints." Detecting these keypoints allows for the application of pathfinding algorithms to reconstruct and measure each individual filament between these points accurately [30] [31]. High-Resolution Networks (HRNet) have proven particularly effective in human keypoint detection due to their ability to maintain high-resolution representations throughout the network, preserving spatial details essential for precise localization [31].

Methodology

The quantification process involves three main stages: binary segmentation of the filament network, detection of keypoints (junctions and endpoints) using a modified ResNet, and finally, filament quantification via a fast marching algorithm. The workflow is depicted in the following diagram.

Binary Segmentation of Actin Filaments

The first step involves generating a binary mask of all actin filaments within the microscopic image.

- Purpose: To isolate the filamentous structures from the background and image noise.

- Protocol:

- Input: 2D maximum intensity projection (MIP) of microscopic image stacks (e.g., 1740 × 840 pixels) [30].

- Network: Utilize a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), such as the U-Net architecture, trained for pixel-wise classification [30].

- Output: A binary image where pixels belonging to actin filaments are labeled as 1, and the background as 0. This output serves as the input for the keypoint detection stage.

Keypoint Detection with Modified ResNet

This is the core component of the framework, where a ResNet architecture is adapted to detect junctions and endpoints.

- Purpose: To accurately localize the coordinates of all junctions and endpoints within the segmented filament network.

- Network Modification and Training Protocol:

- Backbone: ResNet-101 is used as the feature extraction backbone [30].

- Adaptation: The final fully connected layer is replaced with new output heads for keypoint estimation. The standard modification involves two output branches [30]:

- A heatmap branch that produces a probability map for each keypoint type (junction and endpoint).

- An offset map branch (two channels per keypoint) that predicts local displacements to refine the location of each keypoint and achieve sub-pixel accuracy.

- Training Data:

- Due to the difficulty of manually labeling keypoints in dense networks, a synthetic dataset is generated for training [30].

- The protocol involves creating 10,000 images of 128x128 pixels, each containing random, one-pixel-width curves with various junction types. The coordinates of all junctions and endpoints are recorded as ground truth.

- These binary images are then randomly dilated with kernels of size 3 to 7 to simulate the thickness of real, segmented filaments, making the synthetic data visually similar to the experimental data [30].

- Loss Function: The model is trained using a combination of Dice-coefficient loss (for the heatmaps) and L1 loss (for the offset maps) [30].

The architecture and process of keypoint detection are visualized below.

Filament Quantification using Fast Marching

The final step uses the detected keypoints to isolate and measure each filament.

- Purpose: To calculate the number of individual filaments and their respective lengths.

- Protocol:

- Initialization: The detected junction and endpoint coordinates are set as initial contour points (sources) in the fast marching algorithm [30].

- Wave Propagation: The algorithm propagates a "wave" from each source point outward at a constant speed across the binary segmentation. The propagation is constrained to the filament paths (white pixels in the binary image) [30].

- Midpoint Identification: The points where wavefronts from different source points collide are identified as the midpoints of the filaments. The geodesic distance value at these collision points represents half the length of the filament [30].

- Calculation: The length of each filament is obtained by doubling the peak geodesic distance value at its midpoint. The total number of filaments is derived by counting these midpoints [30].

Results and Performance Analysis

The performance of the modified ResNet keypoint detection method was evaluated against other established approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Actin Filament Quantification Methods

| Method | Key Technology | Keypoint Detection Approach | Quantification Basis | Reported Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified ResNet (Proposed) | Deep Learning (ResNet-101) | Heatmap & offset regression on synthetic data | Fast marching from detected keypoints | Outperforms others in accuracy and inference time; avoids skeletonization errors [30] |

| SOAX | Traditional (Stretching Open Active Contours) | Not Applicable | Direct filament tracing | High computational burden; requires manual parameter adjustment [30] |

| Skeletonization-Based | Traditional Computer Vision | Skeletonization & junction disconnection | Length of disconnected components | Skeletonization alters junction geometry, increasing errors [30] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance on Actin Filament Dataset

| Experiment | Percentage Difference in Total Length (vs. Proposed) | Percentage Difference in Filament Count (vs. Proposed) | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOAX [32] | Relatively Low | Much Lower Count | High (can take hours for dense images) [30] |

| Skeletonization-Based [6] | Relatively Low | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Proposed (Modified ResNet) | Reference | Reference | Accurate and Efficient [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Implementation

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| In Vitro Motility Assay (IVMA) | Standard experimental system for studying myosin-driven propulsion of fluorescently labeled actin filaments, generating the raw video data for analysis [6] [7]. |

| Synthetic Dataset for Keypoint Training | Enables training of the ResNet model for junction/endpoint detection in the absence of large, manually-labeled real-world datasets, which are difficult to obtain [30]. |

| Pre-trained CNN for Binary Segmentation | Provides a robust initial model for segmenting filaments from the microscopic background, which can be used directly or fine-tuned for specific experimental conditions [30]. |

| Fast Marching Algorithm (scikit-fmm) | The computational engine for calculating the geodesic paths along filaments between keypoints, from which the final length measurements are derived [30]. |

| ATLAS Software Package | An open-source, machine learning-enhanced software that demonstrates the application of similar principles for automated filament tracking and analysis in IVMA [6] [7]. |

The adaptation of ResNet architectures for keypoint detection provides a robust and accurate solution for the high-throughput quantification of actin filaments. By integrating deep learning-based keypoint detection with a fast marching algorithm, this method overcomes the significant limitations of traditional image processing techniques, particularly in handling dense networks and complex junctions. This protocol offers researchers and drug development professionals a powerful tool for automating the analysis of cytoskeletal dynamics, thereby accelerating research workflows and enhancing the reliability of quantitative data.

MATLAB-Based Tools for Filament Counting, Length Measurement, and Bundling Analysis

Within the context of high-throughput actin filament quantification algorithm research, the ability to accurately extract quantitative data from fluorescence micrographs is paramount. The actin cytoskeleton, a dynamic filamentous network, assembles into specialized structures that enable essential cellular processes such as migration, growth, and division [11]. The development of computational tools that can precisely quantify filamentous structures—specifically their numbers, lengths, and bundling behavior—provides critical insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing cytoskeletal dynamics. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for MATLAB-based tools that facilitate such analyses, enabling researchers to obtain equilibrium and kinetic parameters from a broad range of actin-based reactions and other biopolymer assemblies [33] [11].

These tools address a significant challenge in the analysis of fluorescence microscopy data: the interdependent and kinetic nature of actin assembly reactions, which often complicates accurate tracking of their evolution over time [11]. The presence of overlapping filaments, variations in nucleation, elongation, annealing, and severing rates make it difficult to resolve and track individual filaments. The MATLAB programs described herein overcome these challenges through automated detection coupled with manual resolution of complex filament overlaps, providing a robust framework for high-throughput quantitative analysis.

Computational Methodology and Algorithmic Workflow

The MATLAB-based tools for filament analysis consist of two primary programs: one dedicated to quantifying filament numbers and lengths, and another designed for kinetic measurements of filament bundling. Both programs process fluorescence micrographs, which can be supplied as individual frames or as time-series stacks, enabling both equilibrium and dynamic kinetic analyses [11].

Core Image Processing Pipeline

The initial stage of analysis involves a multi-step image processing pipeline that prepares the raw fluorescence micrographs for accurate filament identification and measurement. The workflow begins with the input of a single micrograph or a time-series stack [11]. The selected image first undergoes noise filtering and background subtraction using two-dimensional Gaussian filters, with standard deviations that can be adjusted by the user to match specific image characteristics. This step is crucial for reducing high-frequency noise and correcting for uneven illumination, which significantly improves subsequent detection accuracy.

Following background correction, the image is normalized by rescaling each pixel's intensity to a value between 0 and 1, standardizing the dynamic range across different experimental conditions. To identify filamentous structures, a thresholding operation is applied where pixels whose intensity values exceed a user-defined minimum threshold are classified as 'detected,' while all other pixels are disregarded. This operation is implemented using MATLAB's graythresh and imbinarize functions, which convert the grayscale image into a binary representation where filaments appear as white objects against a black background [11].

The final preprocessing step is skeletonization, which reduces each two-dimensional filament object to a line with a width of precisely one pixel. This transformation is essential for accurate length measurement, as it preserves the filament's topological structure while eliminating variations in apparent width that could introduce measurement artifacts. The skeletonized representation enables the program to identify individual filament objects based on their morphological characteristics, specifically their endpoints and branch points [11].

Filament Resolution and Error Correction

Following skeletonization, the program systematically assesses each contiguous object to quantify its endpoints. Objects identified as individual filaments typically appear as single lines possessing exactly two endpoints and no branch points. In contrast, objects containing more than two endpoints or at least one branch point are automatically flagged as containing detection "errors," primarily resulting from overlapping or crossing filaments [11].

To resolve these complex cases, the software incorporates an interactive error correction interface that allows users to manually disentangle overlapping filaments. When a detection error is identified, the program sequentially presents each problematic object to the user, with different segments (or "branches") of the overlapping filaments highlighted in distinct colors for clear visualization. The user is then presented with options to either record a highlighted segment as a standalone filament or combine it with another segment to form a single, continuous filament [11]. This interactive approach enables precise resolution of filament overlaps that would be challenging to address through fully automated algorithms alone. The same interface can be used to manually identify and remove instances of fluorescent noise that were erroneously detected as filamentous objects, further enhancing the accuracy of the final analysis.

Length Quantification and Data Export