Encapsulating Actin Cytoskeletons in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles: A Guide for Synthetic Cell Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and professionals on the encapsulation of actin networks in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs), a cornerstone of bottom-up synthetic biology.

Encapsulating Actin Cytoskeletons in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles: A Guide for Synthetic Cell Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and professionals on the encapsulation of actin networks in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs), a cornerstone of bottom-up synthetic biology. We explore the foundational role of the actin cytoskeleton as the cell's primary mechanical machinery and detail the most effective production methods, including inverted emulsion and cDICE, for achieving high encapsulation efficiency. The scope extends to troubleshooting common experimental challenges, validating the resulting synthetic cell constructs through advanced image analysis and functional assays, and comparing the performance of different methodological approaches. This guide synthesizes current best practices to advance the construction of biomimetic artificial cells for fundamental research and therapeutic applications.

The Actin Cytoskeleton and GUVs: Building a Mechanical Framework for Synthetic Cells

Why GUVs are an Ideal Biomimetic System for Cytoskeletal Studies

Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) are micrometer-sized, closed freestanding lipid bilayers that faithfully mimic the size, curvature, and basic structure of the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells [1] [2]. Their cell-like dimensions (typically 1-100 μm) and ease of visualization under optical microscopy have established them as one of the most powerful biomimetic membrane model systems available [1] [2]. In the study of biological processes, simplified models play a crucial role by allowing researchers to analyze complex systems in a controlled environment, much like how maps serve as simplified representations of the Earth [1]. GUVs fulfill this role exceptionally well for membrane and cytoskeletal studies because they enable the reproduction of simplified cell models in the laboratory, making it possible to investigate how membranes and associated structures respond to various stimuli without the complexity of entire biological systems [1].

The principal advantage of GUVs for cytoskeletal research derives from their micron scale, which enables ease of visualization and manipulation using microscopy and microhandling techniques [3]. This unique combination of properties makes GUVs an ideal tool for bottom-up synthetic biology approaches, where purified components are assembled to recreate minimal functional cellular units [4] [5]. Specifically for cytoskeletal studies, GUVs provide a confined reaction space that mimics the physical constraints inside living cells, allowing researchers to investigate how cytoskeletal assemblies form structures that span the entirety of the cell, with their shape naturally determined by cell-sized confinement [4].

Advantages of GUVs for Cytoskeletal Research

Key Benefits for Cytoskeleton-Membrane Interaction Studies

GUVs offer several distinct advantages that make them particularly suitable for studying cytoskeletal networks and their interactions with membranes. First, the ability to precisely control the membrane's molecular composition is fundamental for systematic studies [1]. This composition can range from single lipid species to complex mixtures of several lipids, including natural lipid extracts [1]. Furthermore, GUVs can be functionalized with specific membrane-bound proteins or biotinylated lipids that enable precise attachment of actin filaments or nucleation factors [5].

A second major advantage is the ability to encapsulate cytoskeletal proteins inside the GUVs, creating a cell-like environment where network assembly can occur under controlled confinement [4]. This encapsulation better mimics confinement conditions inside living cells as opposed to conventional biochemical reconstitution [4]. The confinement itself affects actin morphology and organization, which can be systematically studied using GUVs [5].

Third, GUVs serve as a deformable substrate whose mechanical properties can be precisely quantified and related to cytoskeletal activity. Researchers can observe how actin networks generate forces that deform membranes and how these interactions affect overall vesicle shape and mechanics [5] [6]. This has proven essential for understanding physical mechanisms behind cellular processes such as motility, division, and filopodia formation [5].

Table 1: Key Advantages of GUVs for Cytoskeletal Studies

| Feature | Research Benefit | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-like Size | Enables study of cytoskeletal organization under physiological confinement | Actin cortex formation [5]; microtubule network organization [6] |

| Controlled Composition | Systematic analysis of lipid-protein interactions | Membrane attachment via PIP2/N-WASP [5]; lipid raft domains [7] |

| Direct Visualization | Real-time observation of dynamic processes | Actin polymerization dynamics [4]; shape fluctuations [6] |

| Membrane Deformability | Investigation of force generation and mechanical coupling | Actin-driven protrusions [5]; vesicle shape changes [8] [6] |

| Encapsulation Capacity | Study of network assembly in confined space | Minimal cytoskeleton reconstitution [7] [4] [5] |

Comparison of GUV Production Methods for Cytoskeletal Studies

Different methods for GUV production offer varied advantages and limitations, making them differentially suitable for cytoskeletal encapsulation studies. The selection of an appropriate preparation technique is critical to fine-tuning the properties of GUVs and ensuring they are suitable for specific applications [1].

Table 2: Comparison of GUV Production Methods for Cytoskeletal Encapsulation

| Method | Encapsulation Efficiency | Cytoskeletal Compatibility | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroformation [1] | Low | Limited to specific buffers and low ionic strength | Simple equipment; high quality vesicles | Restricted lipid compositions; low salt buffers |

| Gel-Assisted Hydration [1] [2] | Moderate | Compatible with physiological buffers | Works with high ionic strength; simple setup | Polymer contamination possible [2] |

| Emulsion Transfer Methods (cDICE) [4] [9] | High | Excellent for proteins and physiological conditions | High encapsulation efficiency; rapid production | Complex setup; potential oil contamination |

| Microfluidic Methods [10] | High | Good for controlled encapsulation | Size control; high throughput | Technical complexity; device fabrication |

For cytoskeletal studies specifically, emulsion-based methods like continuous droplet interface crossing encapsulation (cDICE) have proven particularly valuable because they allow efficient encapsulation of complex protein systems inside GUVs [4]. This method simplifies the overall procedure of encapsulation within GUVs and speeds up the process, allowing researchers to confine and observe the dynamic evolution of network assembly inside lipid bilayer vesicles [4]. The protocol takes about 15-20 minutes from start to GUV collection and imaging, which is crucial for maintaining the activity of cytoskeletal proteins [4].

Experimental Protocols for Cytoskeletal Reconstitution in GUVs

cDICE Method for Actin Encapsulation

The cDICE technique has emerged as a powerful method for reconstituting cytoskeletal networks inside GUVs due to its high encapsulation efficiency and compatibility with physiological conditions [4]. Below is a detailed protocol for encapsulating actin and actin-binding proteins using this method:

Preparation of Oil-Lipid Mixture (Perform in fume hood):

- Take 0.5 mL of chloroform in a 15 mL glass vial. Add 88 μL of 25 mg/mL DOPC, 9.3 μL of 50 mg/mL cholesterol, and 5 μL of 1 mg/mL dioleoyl-phosphoethanolamine-lissamine rhodamine B (rhodamine PE) [4].

- Pipette 7.2 mL of silicone oil and 1.8 mL of mineral oil in a second 15 mL vial [4].

- Mix the oils by vortexing at maximum rotational speed (3200 RPM) for 10 seconds, then add to the vial containing the lipid-chloroform mixture and vortex immediately for 10-15 seconds at maximum speed [4].

- Sonicate the lipid-in-oil dispersion in a bath sonicator (80 W, 40 kHz) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Use immediately or store at 4°C for maximum 24 hours [4].

Protein Solution Preparation:

- Prepare 1-10 μM of actin in globular actin buffer (G-buffer: 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.2 mM CaCl₂), including 10% fluorescently labeled actin (e.g., ATTO 488 actin) for visualization [4].

- Add filamentous actin polymerization buffer (F-buffer: 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl₂, and 3 mM ATP in 100 mM Tris, pH 7.5) to initiate actin polymerization on ice [4].

- Wait for 15 minutes to allow for initiation of actin polymerization on ice before adding crosslinkers (e.g., fascin, α-actinin) at the desired molar ratio [4].

- Prepare actin-binding proteins (ABPs) separately in microtubes [4].

Vesicle Generation:

- Mount a 3D-printed shaft on a benchtop stir plate and set rotational speed to 1200 RPM [4].

- Mount a 3D-printed cDICE chamber on the shaft [4].

- Add the lipid-in-oil mixture and protein solutions to the rotating chamber following specific timing protocols to ensure proper encapsulation [4].

- Collect GUVs after formation for immediate imaging or further experimentation [4].

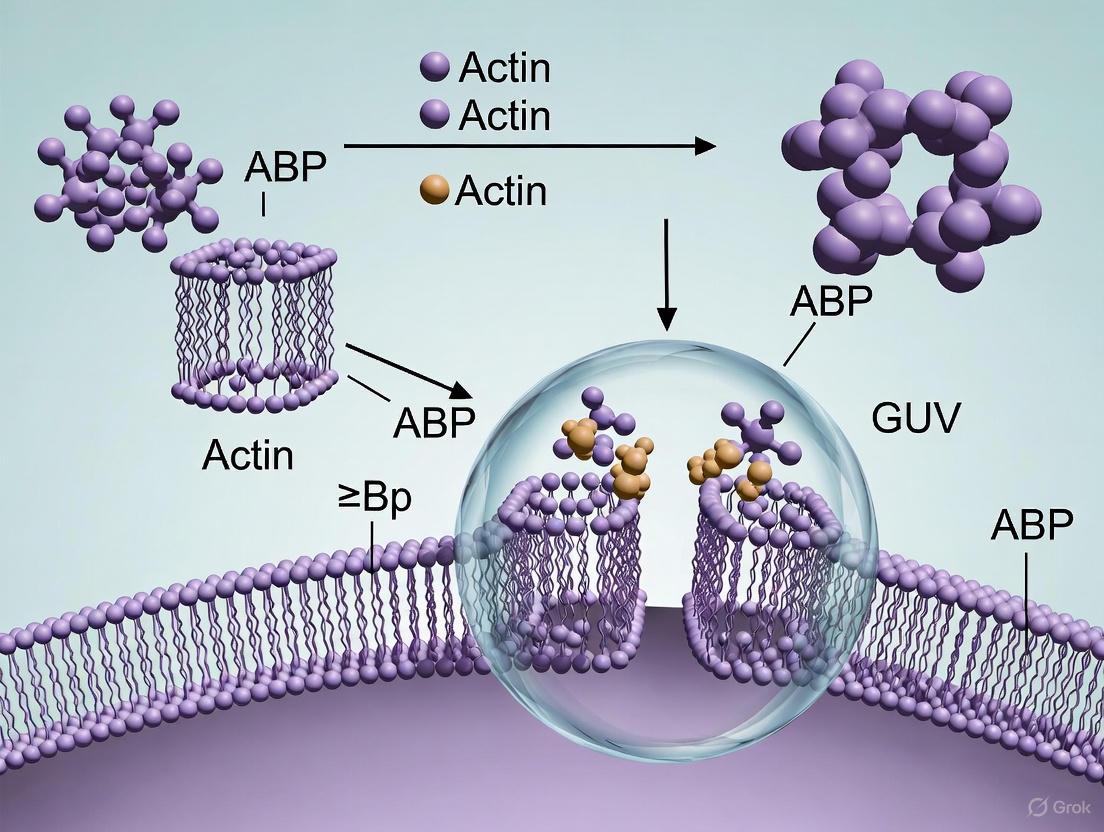

Diagram 1: cDICE workflow for cytoskeletal encapsulation.

Phase-Separated GUVs for Membrane Domain Studies

A more advanced application involves creating phase-separated GUVs containing liquid-disordered (Ld) and liquid-ordered (Lo) domains to better mimic the lipid raft heterogeneity of cellular membranes [7]. The following protocol enables simplified one-pot production of such systems:

Emulsion Transfer Protocol for Phase-Separated GUVs:

- Generate a lipid-monolayer by emulsifying a protein solution in a lipid/oil mixture, selecting lipids of varying phase transition temperatures to yield phase separation in the resultant GUVs [7].

- Gently transfer this emulsion on top of a lipid-in-oil solution in another tube, resulting in the formation of a water-oil interface [7].

- Centrifuge at elevated temperatures (ideally at 37°C to retain protein activity) [7].

- Collect GUVs for imaging and analysis of cytoskeletal organization relative to membrane domains [7].

This method simplifies the in vitro reconstitution of cytoskeletal proteins within phase-separated GUVs without using a cumbersome laboratory setup, serving as a convenient method for studying the mechanics of cytoskeletal-membrane interactions in confinement [7].

Research Applications and Case Studies

Reconstitution of Actin Networks

GUV-based systems have enabled detailed studies of various actin structures and their effects on membrane properties. Researchers have successfully reconstituted multiple actin architectures inside GUVs by varying the composition of actin-binding proteins:

Branched Networks: Using nucleation-promoting factors like N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex, researchers have created branched actin networks similar to those found in lamellipodia [5]. When specifically targeted to the membrane through PIP2 lipids or other attachment strategies, these networks can generate protrusive forces that deform GUV membranes, creating filopodia-like extensions [5]. One study demonstrated that such membrane-coupled actin assembly leads to both inward and outward protrusions emerging from dendritic networks, with the exact deformation pattern dependent on the concentration of capping proteins [5].

Bundled Actin Structures: The addition of crosslinking proteins like fascin and α-actinin to encapsulated actin results in the formation of bundled actin structures [5]. These bundles can organize into ring-like structures near the membrane or form protrusions extending from the GUV surface [5]. Interestingly, the competition between different actin-binding proteins significantly affects network morphology, as demonstrated by Wubshet et al., who showed that fascin and Arp2/3 compete for G-actin, with protrusions forming only in the presence of sufficient fascin concentrations [5].

Actin-Myosin Contractile Systems: The encapsulation of both actin and myosin II motors enables the reconstitution of contractile networks that mimic the actomyosin cortex of cells [5]. These systems can generate tension and lead to dramatic shape changes in GUVs. Studies have shown that the balance between membrane attachment and contractile forces determines whether the cortex remains membrane-associated or detaches, creating cortical discontinuities similar to those observed in certain cellular processes [5].

Microtubule-Motor Systems in GUVs

Beyond actin systems, GUVs have proven valuable for studying microtubule networks and their interactions with membranes. Recent work has encapsulated active microtubule networks driven by kinesin molecular motors inside GUVs [6]. This minimal synthetic cell model demonstrates how cytoskeletal forces acting on a biomimetic membrane affect its deformations:

Active Fluctuation Analysis: When encapsulated inside GUVs, active microtubule networks organize into a three-dimensional network of extensile bundles that continuously exert forces on the membrane [6]. Quantitative analysis reveals fluctuation spectra that differ in both spatial and temporal decays from their counterparts in thermal equilibrium [6]. These active deformations are roughly one order of magnitude greater than passive fluctuations at all mode numbers, following a 〈∣u_q∣^2〉 ≈ q^−3 decay that indicates bending-dominated deformations [6].

Correlated Activity: The membrane dynamics in these systems are governed by correlated activity of the encapsulated cytoskeletal components rather than thermal fluctuations alone [6]. Using simulations, researchers have extended the classical framework of membrane fluctuations to active cytoskeleton-driven vesicles, demonstrating how activity governs membrane dynamics and the roles of confinement, membrane material properties, and cytoskeletal forces [6].

Diagram 2: Cytoskeleton-membrane interactions in GUVs.

Mechanical Stabilization by Actin Networks

Membrane-localized actin filaments have been shown to stabilize GUVs against external deforming forces [8]. This stabilization function mimics the protective role of the cortical actin network in cells, demonstrating how GUVs can be used to study both active deformation processes and mechanical reinforcement provided by cytoskeletal elements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GUV Cytoskeletal Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiments | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | DOPC, Cholesterol, Rhodamine PE | Membrane formation, fluidity control, visualization | Avanti Polar Lipids [4] |

| Cytoskeletal Proteins | Actin (skeletal muscle), ATTO 488-actin | Primary filament formation, visualization | Cytoskeleton Inc., Hypermol [4] |

| Actin-Binding Proteins | Fascin, α-actinin, Arp2/3 complex | Crosslinking, nucleation, network regulation | Homemade, commercial sources [4] [5] |

| Molecular Motors | Myosin II, kinesin tetramers | Force generation, network contraction | Commercial sources [5] [6] |

| Buffers & Reagents | G-buffer, F-buffer, ATP, MgCl₂ | Polymerization control, energy source | Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific [4] |

| Equipment | 3D-printed cDICE chamber, sonicator, vortex | Vesicle production, sample preparation | Formlabs, Fisher Scientific [4] |

Giant Unilamellar Vesicles represent an ideal biomimetic system for cytoskeletal studies due to their unique combination of cell-like size, compositional control, and experimental accessibility. The development of advanced encapsulation techniques like cDICE has enabled researchers to reconstitute increasingly complex cytoskeletal networks inside GUVs, from simple actin filaments to active systems containing multiple cytoskeletal proteins and molecular motors. These minimal systems have provided fundamental insights into the physical mechanisms underlying cytoskeleton-driven membrane deformations, network organization under confinement, and the mechanical stabilization provided by cortical structures.

As GUV technology continues to advance, with improved production methods and more sophisticated biochemical reconstitution capabilities, these biomimetic systems will undoubtedly play an increasingly important role in deciphering the complex interplay between cytoskeletal networks and cellular membranes. The quantitative approaches enabled by GUV-based systems, including flicker spectroscopy, force measurements, and dynamic imaging, provide a solid foundation for building physical models of cell shape changes that bridge the gap between in vitro reconstitution and cellular physiology.

The Role of Actin as the Cell's Principal Mechanical Machinery

The actin cytoskeleton serves as the primary mechanical machinery within eukaryotic cells, generating and withstanding physical forces essential for processes including cell migration, cytokinesis, and morphogenesis [11] [12]. This dynamic polymer network converts chemical energy into mechanical work through its interaction with motor proteins and cross-linking factors, allowing cells to adapt their shape, generate traction, and respond to environmental physical cues [13]. In physiological three-dimensional environments, actin organizes into structures distinct from those observed on two-dimensional substrates, underscoring the importance of studying its mechanics in contextually relevant systems such as giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) [14] [15]. These minimal cell models provide a controlled platform for dissecting how actin architecture dictates mechanical output, a relationship crucial for understanding cell behavior in development, homeostasis, and disease.

Actin Architecture and Force Generation Mechanisms

Structural Organization of Actin Networks

Actin networks assemble into diverse architectures defined by specific actin-binding proteins. The Arp2/3 complex nucleates branched actin networks that produce protrusive forces, while formins processively assemble unbranched actin bundles such as filopodia and stress fibers [15]. Fascin constructs tightly packed, parallel actin bundles that provide rigid structural support for filopodia and other cellular protrusions [16]. These structural variations directly determine the mechanical properties and force-generation capabilities of the cytoskeleton. In GUV-based studies, these distinct architectures demonstrate unique reorganization behaviors when subjected to external forces, with fascin-bundled networks collapsing and aligning along aspiration axes while branched networks resist deformation and maintain structural integrity [14].

Molecular Mechanisms of Contractility

Cellular contractility primarily emerges from the interaction between filamentous actin (F-actin) and myosin II motor proteins [11] [12]. Myosin II molecules self-assemble into bipolar filaments that walk toward the barbed ends of adjacent actin filaments, generating shear forces that pull anti-parallel filaments past one another [12]. In disordered actomyosin networks, compressive forces buckle actin filaments, leaving net tension that drives contraction [11]. Computational models reveal that myosin filament structure—including the number of motor heads, bare zone length, and spatial distribution—profoundly influences both the magnitude and efficiency of force generation [11] [12]. This contractile apparatus enables cells to generate, transmit, and sense mechanical forces with high spatial and temporal precision.

Application Notes: GUVs for Actin Mechanics Research

GUVs as Minimal Cellular Models

Giant unilamellar vesicles provide an ideal reconstitution platform for investigating actin mechanics in a controlled, cell-like environment. When encapsulated within GUVs, actin networks interact with the lipid membrane, enabling researchers to study force transmission and shape changes in a minimal system [14] [17]. Studies demonstrate that polymerized actin significantly increases membrane rigidity, with F-actin accumulating near the membrane and enhancing resistance to deformation [17]. The encapsulation of active cytoskeletal components, including molecular motors and cross-linkers, produces dramatic shape fluctuations and traveling membrane deformations reminiscent of living cells [6]. These reconstituted systems enable precise manipulation of biochemical and physical parameters that is impossible in living cells, making GUVs invaluable for mechanistic studies.

Technical Considerations for Actin Encapsulation

Successful actin encapsulation requires careful optimization of lipid composition, buffer conditions, and polymerization triggers. Phase-separated GUVs with liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered domains better mimic cellular membrane complexity and can be produced using emulsion transfer methods that preserve protein activity [18]. Actin polymerization inside GUVs typically requires MgCl₂ and ion carriers to facilitate Mg²⁺ transport across the membrane [17]. Maintaining physiological temperatures during GUV production is crucial for retaining cytoskeletal protein function, while including crowding agents like Ficoll70 mimics intracellular conditions that promote proper network assembly [18]. These technical considerations ensure the reconstitution of physiologically relevant actin architectures and dynamics.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings from Actin-GUV Studies

| Experimental System | Key Finding | Mechanical Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fascin-bundled actin in GUVs under aspiration | Bundles collapse and align along aspiration axis | Network architecture determines deformation response | [14] |

| F-actin encapsulated in DMPC GUVs | Polymerized actin increases membrane rigidity | Actin networks resist deformation | [17] |

| Active MT/kinesin/anillin networks in GUVs | Correlated activity drives membrane fluctuations | Active forces dictate temporal scaling of deformations | [6] |

| Branched actin networks in GUVs under aspiration | Networks resist entry into micropipette | Interconnected architecture provides structural stability | [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Encapsulation of Actin Networks in Phase-Separated GUVs

This protocol describes the production of phase-separated GUVs containing reconstituted actin networks using an emulsion transfer method, adapted from established techniques [18].

Lipid Mixture Preparation

- Prepare lipid stock solutions in chloroform: DOPC (25 g/L), DOPG (25 g/L), DPPC (25 g/L), DPPG (10 g/L), and Cholesterol (18 g/L)

- Combine in molar ratio DOPC:DOPG:DPPC:DPPG:Chol:Biotinyl CAP PE (17.499:7.5:30.5:13.5:30:1)

- Add 0.001 mol% Atto655-DOPE fluorescent dye for membrane visualization

- Evaporate chloroform under nitrogen gas flow and desiccate for 30 minutes to remove residual solvent

- Resuspend dried lipid film in decane (20 μL) and mineral oil (500 μL) to final concentration of 3.2 mM

- Sonicate lipid-in-oil mixture at 50°C for 30 minutes, then incubate at 37°C before use

Actin Bundle Encapsulation Mixture

- Prepare actin master mix (A-Mix) containing 86% G-actin, 10% Atto488-actin, and 4% biotinylated actin in water

- For final concentration of 35.42 μM A-Mix, combine 6.39 μL of 2 g/L G-actin, 1.48 μL of 1 g/L Atto488-actin, 1.19 μL of 0.5 g/L biotinylated actin, and 0.9 μL H₂O

- Maintain on ice and protect from light until encapsulation

- Add fascin at 1:5 molar ratio to actin to induce bundle formation [14]

GUV Formation via Emulsion Transfer

- Emulsify inner actin solution in lipid/oil mixture by pipetting to create volumetric confinement before full network assembly

- Transfer emulsion to rotating cDICE chamber containing outer aqueous solution (∼200 mOsm) and oil/lipid mixture

- Include 7.5% Optiprep in inner solution to facilitate GUV sedimentation via density gradient

- Centrifuge at elevated temperature (37°C) to maintain protein activity while achieving phase separation

- Collect GUVs for imaging and analysis

GUV Encapsulation Workflow: Diagram outlining the key steps for encapsulating actin networks in phase-separated giant unilamellar vesicles.

Protocol 2: Micropipette Aspiration of Actin-GUVs

This protocol details the application of micropipette aspiration to assess mechanical responses of encapsulated actin networks, building on established methods [14].

Micropipette Preparation

- Pull standard glass capillaries using a Sutter P-87 pipette puller to create parallel-walled tips

- Manually cut pipettes to diameters of 4-8 μm using a heated glass rod

- Submerge pipettes in 1% BSA solution to prevent GUV adhesion

- Mount pipette in holder and connect to fluidic system with filling syringe and pressure transducer

- Eliminate all air bubbles from the system

- Maintain slight positive pressure until GUV is positioned for aspiration

Aspiration and Imaging

- Position GUV (diameter 15-40 μm) adjacent to micropipette using micromanipulator

- Apply negative pressure using pressure transducer to initiate aspiration

- Acquire timelapse images every 300 ms using spinning disk confocal microscopy

- Simultaneously capture fluorescence images of actin networks and brightfield images of pipette tip

- Analyze network reorganization using ImageJ and Python's matplotlib library

Data Analysis

- Extract GUV contour R(φ, t) from equatorial plane images

- Compute membrane deformations ΔR = R - R₀, where R₀ is mean radius

- Decompose contour into Fourier modes to quantify deformation magnitudes

- Perform statistical analysis on intensity profiles pre- and post-aspiration

- Compare deformation spectra between different actin architectures

Mechanical Testing Workflow: Steps for micropipette aspiration of actin-encapsulating GUVs to assess mechanical properties.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Actin-GUV Research

| Reagent | Function | Example Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC/DPPC/Cholesterol lipids | Membrane formation with phase separation | Creating domain-forming GUVs | 70:30 DOPC:Cholesterol ratio common [14] |

| Fascin | Actin bundling protein | Forming parallel actin bundles | 1:5 fascin:actin ratio for bundles [14] |

| Arp2/3 complex with VCA | Nucleates branched actin networks | Creating dendritic architectures | 500 nM Arp2/3 + 500 nM His₆-tag VCA [14] |

| ATTO488-actin | Fluorescent actin labeling | Network visualization | 10% of total actin for imaging [18] |

| Biotinylated actin | Membrane attachment points | Linking cortex to membrane | 4% of total actin concentration [18] |

| Optiprep | Density gradient medium | GUV sedimentation | 7.5% in inner solution [14] |

| MgCl₂ with A23187 ion carrier | Actin polymerization trigger | Inducing F-actin assembly in GUVs | Enables Mg²⁺ transport across membrane [17] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Membrane Deformations

The mechanical behavior of actin-encapsulating GUVs can be quantified through flicker spectroscopy, which analyzes membrane fluctuations by decomposing the GUV contour into Fourier modes [6]. The contour R(φ, t) is described as:

$$R(\phi ,t)={R}{0}\left(1+\sum _{q}^{{q}{\max }}{u}_{q}(t){{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}q\phi }\right)$$

where uq represents the magnitude of deformations at mode number q. For passive vesicles, the power spectrum follows:

$$\left\langle | {u}{q}{| }^{2}\right\rangle \approx \frac{{k}{{\rm{B}}}T}{\kappa }\frac{1}{{q}^{3}+\bar{\sigma }q}$$

where κ is bending rigidity and $\bar{\sigma }=\sigma {R}_{0}^{2}/\kappa$ is normalized tension [6]. Active GUVs exhibit fluctuation spectra approximately one order of magnitude higher than passive vesicles across all mode numbers, indicating that active forces dominate over thermal excitations [6].

Architectural Determinants of Mechanical Response

Actin network architecture profoundly influences mechanical behavior under load. Fascin-bundled networks undergo dramatic reorganization when aspirated, collapsing and aligning parallel to the flow axis [14]. In contrast, Arp2/3-nucleated branched networks resist aspiration, maintaining structural integrity outside the pipette while only the membrane is drawn in [14]. These differential responses emerge from structural properties: fascin bundles form rigid elements that can reorient as units, while branched networks distribute forces through interconnected filaments. Computational models further reveal that myosin II filament structure—including head number and bare zone length—significantly impacts contractile force generation in both bundled and networked architectures [11] [12].

Table 3: Actin Network Properties and Mechanical Responses

| Actin Architecture | Structural Features | Response to Aspiration | Force Generation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fascin-bundled | Parallel filaments, hexagonal packing | Collapse and alignment along flow axis | High rigidity, coordinated contraction |

| Arp2/3-branched | Dendritic network, 70° branches | Resistance to entry, structural maintenance | Distributed stress, isotropic resistance |

| Myosin-activated | Bipolar filaments, cross-linked | Contraction and tension development | Tunable by myosin filament structure |

GUV-encapsulated actin networks provide a powerful reductionist system for elucidating how cytoskeletal architecture dictates cellular mechanical output. The protocols and analyses presented here enable researchers to reconstitute specific actin structures, apply controlled mechanical stimuli, and quantitatively measure material responses. These approaches reveal fundamental design principles whereby structural plasticity of actin-binding proteins like fascin enables adaptation to varied mechanical demands [16], and how motor filament properties tune contractile force generation [11] [12]. For drug development professionals, these minimal systems offer platforms for screening compounds targeting cytoskeletal mechanics with relevance to cancer metastasis, developmental disorders, and degenerative diseases. The continuing refinement of GUV-based actin models promises deeper insights into how cells harness this versatile mechanical machinery to shape form, generate force, and respond to their physical environment.

The reconstitution of actin networks inside giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) represents a cornerstone of bottom-up synthetic biology, aiming to decipher the fundamental principles of cell mechanics and morphology [19]. This approach utilizes minimal systems to investigate complex biological processes by combining lipid membranes with core cytoskeletal components in a controlled biochemical environment [19]. The core objective is to understand how actin architecture, membrane properties, and biochemical regulation interact to direct cellular functions such as shape changes, motility, and division [20]. Research in this field is fundamentally concerned with three interconnected key challenges: the spatial confinement of networks within cell-sized volumes, their dynamic interactions with lipid membranes, and the precise biochemical regulation of actin dynamics [20]. This Application Note details the experimental frameworks and protocols required to address these challenges, providing researchers with validated methodologies to advance the study of minimal cellular systems.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Encapsulation of Actin Networks in GUVs via cDICE

This protocol describes a method for efficiently encapsulating various actin network architectures inside GUVs, forming a foundational minimal cell model for mechanical perturbation studies [14].

Key Materials:

- Lipids: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), Cholesterol (Chol), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid)succinyl] (DGS-NTA(Ni)) for protein coupling [14].

- Proteins: Purified actin (e.g., rabbit muscle actin), fluorescently-labeled actin (e.g., ATTO 488), and actin-binding proteins (e.g., fascin, Arp2/3 complex, His₆-tag VCA) [14].

- Buffers: General Actin Buffer (G-buffer: 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 mM CaCl₂) and Actin Polymerization Buffer (F-buffer: supplemented with KCl, MgCl₂, and ATP) [14].

- Equipment: cDICE (continuous Droplet Interface Crossing Encapsulation) setup, inverted fluorescence microscope with spinning disk confocal, and EMCCD camera [14].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Inner Solution: Reconstitute filamentous actin by incubating 5.3 µM actin with 0.53 µM ATTO 488-labeled actin in F-buffer supplemented with 3 mM ATP on ice for 15 minutes. For branched bundles, add 500 nM Arp2/3 complex and 500 nM His₆-tag VCA to the polymerizing actin [14].

- Add Density Modifier: Include 7.5% Optiprep in the final inner solution to facilitate GUV sedimentation via a density gradient [14].

- Emulsify: Immediately after adding actin-binding proteins, emulsify the inner solution in a lipid/oil mixture (e.g., 20/80% v/v mineral oil/silicon oil) by pipetting to create volumetric confinement before full network assembly [14].

- Form GUVs via cDICE: Dispense the emulsion into a rotating cDICE chamber containing a layered outer aqueous solution (~200 mOsm) and an oil/lipid mixture (e.g., DOPC/Chol at 70/30 mol/mol). Centrifugal forces promote GUV formation at the liquid interfaces [14].

- Sediment and Collect: Allow the formed GUVs to sediment out of the oil phase due to the density difference provided by Optiprep [14].

The following workflow diagram summarizes this encapsulation process:

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Immobilization for High-Throughput Analysis

This protocol enables the sequential treatment and long-term monitoring of dozens of immobilized GUVs, facilitating statistical analysis of actin-induced membrane remodeling [19].

Key Materials:

- Microfluidic Chips: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chambers.

- Passivation Reagents: Poly(L-lysine)-graft-poly(ethylene glycol) (PLL-PEG) to prevent protein and lipid adsorption on PDMS [19].

- Proteins: Actin, Arp2/3 complex, profilin, Capping Protein (CP), and streptavidin-pVCA-histidine (SpVCA-His) to nucleate networks at the membrane [19].

- Buffers: Polymerization buffer (e.g., 1 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl₂, 0.1 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP) osmotically matched with sucrose [19].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Chip Passivation: Treat the PDMS microfluidic chambers with PLL-PEG to create a non-adhesive surface [19].

- Load and Immobilize GUVs: Introduce the GUV suspension into the microfluidic chamber. The design should include physical traps to isolate individual GUVs [19].

- Introduce Actin Machinery: Perfuse the chamber with a solution containing actin (e.g., 2 µM), Arp2/3 complex, profilin, CP, and other regulatory proteins to initiate actin network formation at the GUV membrane [19].

- Image and Analyze: Use time-lapse fluorescence and brightfield microscopy to monitor the evolution of the actin network and membrane shape across the entire population of trapped GUVs [19].

Protocol 3: Micropipette Aspiration for Mechanical Perturbation

This protocol repurposes micropipette aspiration to apply localized stress and study the dynamic reorganization of GUV-confined actin networks in a architecture-dependent manner [14].

Key Materials:

- Micropipettes: Standard glass capillaries pulled and cut to a tip diameter of 4-8 µm.

- Passivation Solution: 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to prevent GUV adhesion.

- Equipment: Micropipette puller, micromanipulator, pressure transducer, and an inverted microscope equipped for fluorescence imaging [14].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Micropipettes: Pull glass capillaries to create fine tips. Cut tips to the desired diameter using a heated glass rod and submerge them in 1% BSA for passivation [14].

- Set Up Fluidics: Mount the pipette on a holder and connect it via a fluidic line to a filling syringe and a pressure transducer. Eliminate all air bubbles and fill the system with a solution osmotically matched to the GUV interior [14].

- Approach and Aspirate: Use a micromanipulator to bring the pipette tip close to a target GUV. Apply a defined negative pressure via the pressure transducer to aspirate the GUV [14].

- Image Dynamics: Acquire simultaneous fluorescence (to visualize actin network rearrangement) and brightfield (to track the membrane and pipette) timelapse images (e.g., every 300 ms) throughout the aspiration process [14].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Analysis of Actin Network Mechanics

The mechanical properties of GUVs are profoundly altered by the encapsulated actin networks. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings on how different actin architectures influence GUV deformability.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of GUVs Containing Different Actin Networks

| Encapsulated Content | Experimental Method | Key Quantitative Finding | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin-free GUVs [21] | AC Electric Field Electrodeformation | Large electromechanical deformations | The membrane alone offers little resistance to deformation. |

| Actin Filaments [21] | AC Electric Field Electrodeformation | Significantly dampened deformation | Filaments provide internal resistance, increasing stiffness. |

| α-Actinin Cross-linked Networks [21] | AC Electric Field Electrodeformation | Decreased deformability compared to filament networks | Cross-linking creates a stiffer, more solid-like network. |

| Membrane-Associated Dendritic Cortex [21] | AC Electric Field Electrodeformation | Greatly dampened electrodeformation | A cortex anchored to the membrane most effectively resists global shape change. |

| Fascin-Bundled Networks [14] | Micropipette Aspiration | Bundles collapse and align along the aspiration axis | Bundles are dynamic and can reorganize under flow and stress. |

| Branched-Bundled Networks [14] | Micropipette Aspiration | Network remains intact outside the pipette during aspiration | Branching creates a rigid, interconnected structure resistant to flow. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful reconstitution requires high-purity components. The table below lists critical reagents and their functions as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GUV-Actin Reconstitution

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Reconstitution | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| DOPC & Cholesterol | Primary lipid components for forming the GUV membrane bilayer [14]. | Avanti Polar Lipids [14] |

| DGS-NTA(Ni) | Functionalized lipid for coupling his-tagged proteins (e.g., NPF) to the membrane [19]. | Avanti Polar Lipids [19] |

| Purified Actin | Core structural protein for building filaments and networks [14]. | Cytoskeleton, Inc. [14] |

| Arp2/3 Complex | Nucleates new actin filaments from the sides of existing ones, creating branched networks [19]. | Cytoskeleton, Inc. [19] |

| His-tagged VCA | Nucleation Promoting Factor (NPF) that activates Arp2/3 complex; membrane-anchored via NTA-Ni linkage [14]. | Recombinant source [14] |

| Fascin | Cross-links actin filaments into tight, parallel bundles [14]. | Recombinant source [14] |

| Profilin | Binds actin monomers, promotes nucleotide exchange, and enhances polymerization at barbed ends [19]. | Cytoskeleton, Inc. [19] |

| Capping Protein (CP) | Binds filament barbed ends, halting assembly/disassembly and regulating network architecture [19]. | Hypermol [19] |

| PLL-PEG | Polymer used to passivate surfaces (e.g., glass, PDMS), preventing non-specific adhesion of proteins and lipids [19]. | SuSoS [19] |

Discussion of Key Challenges

Navigating Confinement and Size Control

The cell interior is a physically constrained environment where boundaries and limited component availability directly impact biochemical processes [20]. Reconstituting actin networks within GUVs directly addresses this, as the encapsulation volume is in the micrometer range. A major challenge is the global depletion of monomers and regulatory proteins due to this limited volume. Research shows that confinement can be used not just as a mechanical constraint but also to study how global component limitation affects the long-term maintenance of actin dynamics and the coexistence of competitive networks [20]. Furthermore, the physical boundaries can guide the spatial organization of the system, affecting filament curvature and overall network architecture [20].

Mastering Membrane-Actin Interactions

The interplay between actin networks and lipid membranes is a dynamic two-way street. A key finding from reconstitution studies is that branched actin networks nucleated by the Arp2/3 complex possess an inherent ability to sense membrane curvature [22]. These networks preferentially assemble at regions of negative or convex curvature, such as the necks of dumbbell-shaped GUVs [22]. Reciprocally, actin assembly exerts forces on the membrane. The transition from a symmetric actin shell to a polarized "comet tail" that propels a GUV is a classic example of symmetry breaking driven by polymerization-induced compressive forces [19]. This force generation is fundamental to cell-like processes such as protrusion and motility. Additionally, actin networks directly influence membrane organization by stabilizing lipid microdomains and preventing their coalescence [19]. The following diagram illustrates this complex interplay:

Achieving Precise Biochemical Regulation

The dynamic properties of actin networks—their size, turnover, and architecture—are exquisitely regulated by a suite of actin-binding proteins. A fundamental challenge is defining the minimal set of components required to reconstitute a specific process, which is a primary advantage of using purified proteins over cell extracts [20]. The precise concentrations and ratios of actors like profilin, capping protein, and NPFs determine the balance between assembly and disassembly, thereby setting the steady-state size and turnover rate of the network [20] [19]. Furthermore, the activity of regulatory proteins is itself influenced by the network architecture, creating a complex feedback loop where biochemistry and mechanics are intertwined [20]. For instance, the depolymerization and capping activity of proteins like gelsolin can be modulated by phosphoinositides such as PIP₂ and PIP₃, adding another layer of biochemical control that can be studied in reconstituted assays [23].

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) serving as minimal cell models have revolutionized our ability to study cellular processes in a controlled, bottom-up manner. The encapsulation of actin networks within GUVs represents a particularly powerful approach for reconstituting cytoskeleton-dependent functions, enabling researchers to dissect the fundamental principles governing cell shape, mechanics, and response to physical forces. This Application Note details key methodologies and quantitative findings from recent investigations into actin-encapsulating GUVs, highlighting their dual applications in mimicking cellular processes and advancing therapeutic delivery systems. By providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks, we aim to equip researchers with the tools necessary to leverage these biomimetic systems for both fundamental biological discovery and applied biotechnological development.

Core Applications and Quantitative Analysis

Mechanical Phenotyping of Actin Networks

Encapsulated actin architectures demonstrate distinct mechanical responses when subjected to external forces, enabling mechanical phenotyping of network types. Micropipette aspiration experiments reveal that network reorganization depends critically on actin-binding proteins and network geometry.

Table 1: Mechanical Responses of Actin Networks to Micropipette Aspiration

| Network Type | Composition | Aspiration Response | Network Rearrangement | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bundled Networks | Actin + Fascin (1:5 ratio) | Collapse and alignment along aspiration axis | Filaments reorient parallel to pipette axis | Demonstrates adaptive reorientation under flow-induced stress [14] |

| Branched-Bundled Networks | Actin + Fascin + Arp2/3 + VCA | Network resists entry into pipette | Maintains structural integrity outside pipette | Branching stabilizes architecture against deformation [14] |

| Membrane-Associated Cortex | Actin + Crowders | Stabilizes GUV against deformation | Not specified | Reinforces membrane mechanical integrity [8] |

Active Shape Dynamics and Fluctuation Analysis

The encapsulation of active cytoskeletal components generates autonomous shape dynamics that mimic living cells. When powered by ATP, these systems exhibit fluctuations that deviate significantly from thermal equilibrium.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Vesicle Fluctuations in Passive vs. Active Systems

| Parameter | Passive Vesicles | Active Vesicles (MT-based) | Measurement Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluctuation Magnitude | ~1-5% R₀ | ~20% R₀ (enhanced) | Indicates non-thermal, activity-driven deformations [6] |

| Spectral Scaling | ⟨∣uₙ∣²⟩ ~ q⁻³ (bending) or ~q⁻¹ (tension) | ⟨∣uₙ∣²⟩ ~ q⁻³ (enhanced amplitude) | Active forces dominate over thermal fluctuations [6] |

| Temporal Correlation | Exponential decay, τₙ ~ (q³ + σ¯q)⁻¹ | Broken spatial-temporal relationship | Activity modifies relaxation dynamics [6] |

| Distribution Shape | Gaussian | Non-Gaussian at short timescales | Reflects non-equilibrium active processes [6] |

| Bending Rigidity | κₚₐₛₛ = 13.4 ± 2.5 kₚT | Not quantified | Baseline mechanical property [6] |

Experimental Protocols

GUV Encapsulation of Actin Networks via cDICE

The continuous droplet interface crossing encapsulation (cDICE) method enables robust encapsulation of actin networks within GUVs under physiological osmotic conditions [14] [6].

Materials:

- Lipids: DOPC, cholesterol (70:30 mol:mol) [14]

- Actin System: Purified actin, ATTO 488-labeled actin, fascin, Arp2/3 complex, His₆-tag VCA [14]

- Buffers: G-buffer (globular actin), F-buffer (polymerization) [14]

- Density Medium: Optiprep (7.5% final) to facilitate sedimentation [14]

Procedure:

- Prepare Inner Solution: Combine 5.3 μM actin with 0.53 μM ATTO 488 actin in F-buffer with 3 mM ATP. Incubate on ice for 15 minutes to pre-polymerize filaments [14].

- Initiate Network Assembly: Add fascin (1:5 ratio to actin) for bundles, or 500 nM Arp2/3 complex + 500 nM VCA for branched networks [14].

- Emulsify: Immediately emulsify the inner solution in lipid/oil mixture via pipetting to create volumetric confinement before full network assembly [14].

- Form GUVs: Dispense emulsions into rotating cDICE chamber containing osmotically matched outer aqueous solution and oil/lipid mixture. Centrifuge to form GUVs [14] [6].

- Sediment and Harvest: Utilize density difference for sedimentation. Collect GUVs for experimentation [14].

Micropipette Aspiration for Mechanical Perturbation

This protocol details the application of localized stress to actin-encapsulating GUVs to probe network mechanical properties [14].

Materials:

- Micropipettes: Standard glass capillaries (pulled with Sutter P-87 puller) [14]

- Pressure Control: High-speed pressure clamp, pressure transducer [14]

- BSA Solution: 1% for coating pipettes to prevent adhesion [14]

Procedure:

- Prepare Pipettes: Pull capillaries to create parallel-walled tips. Cut to 4-8 μm diameter using heated glass rod. Submerge in 1% BSA solution to prevent adhesion [14].

- Setup Fluidics: Mount pipette in holder. Connect three-way valve between filling syringe, micropipette, and fluid reservoir. Eliminate all air bubbles from system [14].

- Position GUV: Maintain slight positive pressure while positioning GUV near pipette tip using micromanipulator [14].

- Apply Aspiration: Induce aspiration by applying negative pressure via pressure transducer. Typical GUV diameters: 15-40 μm [14].

- Image Dynamics: Acquire timelapse images every 300 ms using confocal microscopy to track network reorganization [14].

Alternative Confinement: Microwell Fabrication

For imaging-compatible confinement without membranes, NOA-based microwells provide precise geometric control [24].

Materials:

- Optical Adhesive: NOA 81 [24]

- Mold Materials: SU8 3000 series, PDMS, epoxy resin [24]

- Passivation Reagents: Silane-PEG 30k Da, EggPC, Pluronic F-127 [24]

Procedure:

- Fabricate Molds: Create SU8 master molds using UV lithography. Generate secondary PDMS molds, then epoxy molds for durability [24].

- Cast Microwells: Polymerize NOA 81 between coverglass and epoxy mold under UV exposure [24].

- Passivate Surfaces: Treat with Silane-PEG or lipid mixtures (EggPC with ATTO 647N-labeled DOPE) to create biologically inert surfaces [24].

- Load Samples: Introduce protein reaction mixes into wells. Seal with mineral oil for long-term imaging [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for GUV Actin Encapsulation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Actin | Core filament-forming protein | Cytoskeleton, Inc. [14] |

| ATTO 488 Actin | Fluorescent labeling for visualization | Hypermol [14] |

| Fascin | Actin bundling protein | Purified in-house [14] |

| Arp2/3 Complex | Nucleates branched actin networks | Cytoskeleton, Inc. [14] |

| VCA Domain | Activates Arp2/3 complex | Purified in-house (His₆-tag) [14] |

| DOPC Lipids | Primary lipid for GUV formation | Avanti Polar Lipids [14] |

| DGS-NTA(Ni) | Membrane anchor for his-tagged proteins | Avanti Polar Lipids [14] |

| Optiprep | Density medium for GUV sedimentation | Sigma Aldrich [14] |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Network Responses

GUV Encapsulation and Mechanical Testing Workflow

Actin Network Responses to Mechanical Stress

GUV-encapsulated actin networks provide a versatile platform for investigating cytoskeletal mechanics and dynamics in cell-sized compartments. The methodologies outlined herein enable systematic exploration of how specific actin architectures respond to mechanical cues, revealing fundamental principles of cellular mechanobiology. These minimal systems not only advance our understanding of cell division and morphogenesis but also pave the way for engineering synthetic cellular systems with applications in targeted drug delivery and diagnostic technologies. The integration of quantitative mechanical analysis with biochemical specificity positions GUV-based models as indispensable tools for bridging molecular-level mechanisms with cellular-scale behaviors.

Best Practices for GUV Production and High-Efficiency Actin Encapsulation

In bottom-up synthetic biology, the construction of artificial cells often relies on giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) as foundational compartments due to their biomimetic properties and similarity in size to mammalian cells [25]. A central challenge in this field is the efficient encapsulation of complex biological machinery, particularly actin cytoskeleton networks, which are essential for achieving cellular functions like shape changes, motility, and division [26] [27]. The encapsulation efficiency and viability of these macromolecules are highly dependent on the GUV production method employed. This application note provides a detailed comparison of three core techniques—Inverted Emulsion, cDICE, and Gel-Assisted Hydration—focusing on their operational parameters, encapsulation capabilities, and suitability for actin-related research. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this document includes structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource guides to inform method selection and implementation.

Comparative Analysis of GUV Formation Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary methods for GUV formation, enabling researchers to select the most appropriate technique based on experimental requirements.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of GUV Production Methods for Actin Encapsulation

| Feature | Inverted Emulsion | cDICE (Continuous Droplet Interface Crossing Encapsulation) | Gel-Assisted Hydration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Phase transfer of water-in-oil emulsion droplets across a lipid-laden interface [25] | Continuous emulsion templating and transfer via a rotating chamber [26] | Swelling of a lipid film on a hydrated polymer gel surface [28] |

| Typical GUV Yield | High (with optimized parameters) [25] | High [26] | Variable, depends on lipid composition and gel [28] |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | High for large biomolecules and micron-sized particles [25] | High, "lossless encapsulation" of biomolecules [25] | Can be enhanced by combining with inverse-phase methods [28] |

| Actin Encapsulation Suitability | Excellent; used for reconstituting contractile actomyosin rings and cortices [26] [27] | Excellent; optimized for high-yield encapsulation of functional proteins like actin [26] | Suitable, especially when combined with inverse-phase methods for complexation [28] |

| Biomimetic Buffer Compatibility | Yes; works in physiological salt and buffer conditions [25] | Yes [26] | Yes; swelling buffer can contain diverse biorelevant molecules [28] |

| Membrane Oil Residue | Potential concern, but studies show no significant alteration of mechanics [25] | Potential concern, depending on oil phase used | Not applicable; oil-free method |

| Key Advantage | Rapid production, high encapsulation efficiency, compatibility with microtiter plates [25] | High throughput, monodisperse GUVs, high encapsulation precision [25] [26] | Broad compatibility with lipid compositions, gentle process (no energy input) [28] |

| Primary Limitation | Requires optimization of multiple parameters (density, centrifugation) [25] | Complex instrumental setup [25] | Lower encapsulation efficiency for macromolecules unless modified [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Inverted Emulsion Method for Actin Encapsulation

This protocol is adapted for the encapsulation of actin and associated proteins, based on optimized parameters from the literature [25] [27].

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Lipid-in-Oil Solution: 1 mM lipid mixture (e.g., POPC with 1% biotinylated lipid for membrane anchoring) dissolved in mineral oil.

- Inner Aqueous Solution (for emulsion): Sucrose-based solution (e.g., 400 mM) containing the proteins to be encapsulated (e.g., G-actin, cross-linking proteins, neutravidin if using biotinylated anchors).

- Outer Aqueous Solution: Glucose-based solution (e.g., 350 mM) of lower density than the inner solution, to facilitate vesicle settling.

Procedure:

- Form the Lipid Monolayer Interface: In a microtiter plate well, add 100 µL of the lipid-in-oil solution. Carefully underlay this with 100 µL of the outer glucose solution. Allow the interface to incubate for 10-15 minutes at room temperature for monolayer formation.

- Prepare the Water-in-Oil Emulsion: In a separate vial, vigorously mix 20 µL of the dense inner aqueous solution (containing your biomolecules) with 100 µL of the lipid-in-oil solution to create a water-in-oil emulsion.

- Transfer Emulsion and Centrifuge: Gently pipette the emulsion and layer it on top of the interface prepared in step 1.

- Centrifuge: Place the plate in a centrifuge and spin at 2,000-5,000 x g for 10-30 minutes. The optimal speed and time must be determined empirically to maximize yield [25].

- Collect GUVs: After centrifugation, the GUVs will have settled at the bottom of the well in the outer aqueous phase. They can be carefully pipetted for observation or further experimentation.

Diagram: Workflow of the Inverted Emulsion Method

cDICE Method for High-Yield Actin Network Encapsulation

The cDICE method allows for the efficient and reproducible encapsulation of sensitive protein complexes like actin networks [26].

Key Reagents and Setup:

- Lipid Solution: 2 mg/mL lipid mixture (e.g., POPC) in an oil/ether mixture.

- Aqueous Solution: Contains all components for the internal reaction (e.g., G-actin, bundling proteins, motor proteins, polymerization buffer).

- Apparatus: A rotating chamber whose walls are pre-coated with the lipid solution. The aqueous solution is injected as droplets into the rotating chamber filled with a denser outer solution (e.g., sucrose).

Procedure:

- Prepare the Chamber: Coat the interior of a spherical rotating chamber with the lipid solution, allowing the solvent to evaporate and form a dry lipid film.

- Fill the Chamber: Add the outer aqueous solution (e.g., glucose-based) to the chamber.

- Initiate Rotation and Injection: Rotate the chamber at a constant speed (e.g., 600-1200 rpm). Inject the inner aqueous solution (containing actin and proteins) into the center of the rotating chamber. Droplets form and are stabilized by a lipid monolayer from the film.

- Vesicle Formation: As droplets travel through the lipid-laden outer solution, they cross a second interface, picking up a second lipid leaflet to become GUVs.

- Harvest GUVs: After rotation stops, collect the GUVs from the chamber.

Diagram: Conceptual Workflow of the cDICE Method

Gel-Assisted Hydration for Sensitive Lipid Compositions

This method is ideal for swelling GUVs from lipid compositions that are sensitive to mechanical stress or oil residues [28].

Key Reagents:

- Polymer Gel Substrate: A dried film of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or agarose on a coverglass.

- Lipid Solution: 0.5-2 mg/mL lipid mixture in an organic solvent (e.g., chloroform).

- Swelling Buffer: An aqueous buffer at the desired osmolarity and pH.

Procedure:

- Prepare the Gel Substrate: Deposit a drop of PVA or agarose solution on a coverglass and allow it to dry completely to form a thin gel film.

- Deposit Lipid Film: Spot the lipid solution onto the dried gel surface and allow the solvent to evaporate, leaving a dry lipid film.

- Hydrate: Place the coverglass in a hydration chamber, add the swelling buffer, and seal the chamber.

- Swelling: Incubate the chamber at a suitable temperature (e.g., 37-50°C) for 1-2 hours to allow GUVs to swell from the lipid film on the gel surface.

- Collect GUVs: Gently agitate the chamber and pipette the supernatant containing the detached GUVs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents used in the featured experiments for actin encapsulation, along with their critical functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Actin Encapsulation in GUVs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Encapsulation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Biotinylated Lipids (e.g., DGS-NTA(Ni)) | Provides membrane anchoring points for His-tagged proteins via neutravidin/biotin linkage [26] [27] | Anchoring His-tagged nucleators (mDia1, VCA) to the inner leaflet for cortex assembly [27] |

| F-actin Nucleators (mDia1, Arp2/3) | Controls the architecture of the encapsulated actin network (linear vs. branched) [27] | Reconstituting distinct cortex architectures to study their role in membrane deformation [27] |

| Actin Cross-linkers (Fascin, α-Actinin) | Bundles actin filaments into higher-order structures, influencing network mechanics [26] | Forming thick actin bundles and rings inside GUVs [26] |

| Membrane Anchor Proteins (Talin/Vinculin) | Links actin filaments directly to the lipid membrane, promoting cortical attachment [26] | Achieving near 100% probability of membrane-bound actin ring formation [26] |

| Sucrose/Glucose Solutions | Creates density gradients essential for phase separation and GUV settling in emulsion-based methods [25] | Forming the inner and outer aqueous phases in the inverted emulsion method [25] [27] |

Critical Parameter Optimization

Successful implementation of these methods, particularly the inverted emulsion technique, requires careful attention to several key parameters. The table below summarizes optimization findings.

Table 3: Key Optimization Parameters for the Inverted Emulsion Method [25]

| Parameter | Impact on GUV Formation | Optimization Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient | Crucial for driving emulsion droplets through the interface; ensures GUVs settle for easy collection [25] | Ensure inner aqueous phase (e.g., sucrose) is denser than outer phase (e.g., glucose). |

| Centrifugation Speed/Time | Directly affects yield; insufficient force prevents transfer, excessive force may disrupt vesicles [25] | Optimize between 2,000-5,000 x g for 10-30 minutes. |

| Lipid Concentration | Impacts the quality of the monolayers at the interface and around emulsion droplets [25] | Test concentrations around 0.5 - 2 mM; 1 mM is a common starting point. |

| Monolayer Incubation Time | Allows for the formation of a stable lipid monolayer at the oil-water interface [25] | Allow 10-15 minutes for monolayer formation before adding emulsion. |

| pH & Temperature | Can affect lipid packing and monolayer stability during formation [25] | Maintain a consistent, physiologically relevant pH and temperature. |

The selection of a GUV production method is a critical determinant in the success of actin encapsulation experiments. The Inverted Emulsion method offers a robust balance of high encapsulation efficiency and operational simplicity, making it an excellent choice for many laboratories seeking to incorporate cytoskeletal components. The cDICE technique, while requiring more specialized equipment, provides superior control over vesicle size and is highly effective for encapsulating complex, functional protein networks with high reproducibility. Finally, Gel-Assisted Hydration presents a gentle, oil-free alternative, ideal for studies where membrane composition is paramount and potential oil residue is a concern. By leveraging the optimized protocols and comparative data provided herein, researchers can strategically select and implement the most appropriate methodology to advance their work in synthetic biology and drug development.

The reconstitution of cytoskeletal components, such as actin networks, within giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) represents a significant stride in bottom-up synthetic biology, aiming to emulate critical cellular functions like mechanical stability and shape changes in artificial cells [17]. The encapsulation of proteins into GUVs presents a unique challenge, as standard formation methods can be inefficient with complex biological mixtures. This protocol details the inverted emulsion technique, optimized for the high-yield encapsulation of actin and its binding proteins, enabling the study of actin's mechanical role under cell-like confinement [29] [17]. By modifying established protocols with key parameters like prolonged waiting time and chloroform addition, researchers can achieve efficient GUV formation and protein encapsulation, paving the way for investigating actin dynamics and membrane-protein interactions in a controlled, cell-free environment [29].

Materials

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials required for the inverted emulsion method to encapsulate actin in GUVs.

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) | A neutral phospholipid used to form the primary lipid bilayer of the GUVs, providing a synthetic membrane structure [30]. |

| Chloroform | An organic solvent added to the lipid-dispersed oil to enhance GUV formation efficiency by promoting lipid aggregation and improving adsorption at the oil-water interface [29]. |

| Mineral Oil | The oil phase used to create the water-in-oil emulsion, which is a critical first step in the inverted emulsion method. |

| Sucrose Solution | A dense sugar solution used for the inner aqueous phase (e.g., containing actin); its density aids in the subsequent phase transfer of GUVs [29]. |

| Glucose Solution | A less dense sugar solution used for the outer aqueous phase; the density difference between inner and outer solutions helps in sedimenting and cleaning the formed GUVs. |

| G-Actin (Monomeric) | The globular, monomeric form of actin to be encapsulated. It can be polymerized into F-actin inside the GUVs to study its mechanical effects [17]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | A salt solution used to promote the polymerization of G-actin into filamentous F-actin inside the GUVs [17]. |

| Ion Carrier A23187 | A molecule that facilitates the transport of Mg²⁺ ions across the lipid bilayer to trigger actin polymerization inside the GUVs [17]. |

| Fluorescently Labelled Lipid (e.g., Rhodamine-PE) | A lipid conjugated to a fluorophore (like Rhodamine B) that is incorporated in small amounts into the bilayer to enable visualization of the GUV membrane via fluorescence microscopy [30]. |

Equipment

- Plasma oxidizer [30]

- Orbital shaker [30]

- Incubator (capable of maintaining 22-23°C and 45°C) [29] [30]

- Desiccator/vacuum [30]

- Confocal or epifluorescence microscope [29] [30]

- Microcentrifuges

- Vortex mixer [30]

- Round-bottom glass test tubes

- Clinical centrifuge

Methods

Experimental Workflow for Actin Encapsulation

The following diagram outlines the complete encapsulation process, from lipid film preparation to final observation.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Lipid Preparation and Monolayer Formation

- Lipid Solution Preparation: Dissolve purified lipids (e.g., DOPC) in a mixture of 90-95% mineral oil and 5-10% chloroform (Δ = 5-10%) to create a 1-2 mM lipid solution. The inclusion of chloroform is critical, as it significantly enhances GUV formation and encapsulation efficiency [29].

- Form Primary Emulsion: In a glass tube, combine the lipid-oil solution with the inner aqueous solution (e.g., G-actin in sucrose buffer). The total volume ratio should be approximately 1:1. Vortex the mixture vigorously for 1-2 minutes to form a stable water-in-oil (w/o) emulsion, where the aqueous droplets are surrounded by a lipid monolayer.

- Monolayer Incubation: Let the primary emulsion rest for a prolonged waiting time (τ = 120 minutes). This extended period is crucial for the lipid monolayer to fully stabilize at the oil-water interface, which directly increases the fraction of larger GUVs (>5 µm) in the final population [29].

GUV Formation and Harvesting

- Form GUVs via Centrifugation: Carefully layer the incubated emulsion on top of a dense sucrose solution in a centrifuge tube. Subject the tube to gentle centrifugation (e.g., 1,500 × g for 15-30 minutes). This forces the emulsion droplets through the interface, where a second lipid monolayer assembles, forming a bilayer and releasing the GUVs into the lower aqueous solution [29].

- Collect GUVs: After centrifugation, a pellet of GUVs will be visible. Carefully collect these GUVs from the bottom of the tube using a pipette. They can be washed by resuspending in an isotonic glucose solution to remove excess oil and non-encapsulated material.

Internal Actin Polymerization

- To polymerize the encapsulated G-actin into F-actin inside the GUVs, add MgCl₂ (to a final concentration of 2 mM) and the ion carrier A23187 (to a final concentration of 1 µM) to the GUV suspension [17]. The ion carrier is essential for transporting Mg²⁺ ions across the lipid bilayer to initiate the polymerization reaction within the GUV lumen.

- Incubate the GUVs at room temperature (22-23°C) for 30-90 minutes to allow for complete actin filament formation [29] [17].

Key Optimization Parameters

The table below summarizes the quantitative effects of two key protocol parameters on GUV formation, based on statistical analysis [29].

| Parameter | Total GUV Number | Encapsulation Efficiency | Number of GUVs >5µm | Fraction of GUVs >5µm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform Addition (Δ) | Significant Increase (p < 0.001 for 0% vs. 10%) [29] | Significant Increase (p < 0.001 for 0% vs. 5% and 0% vs. 10%) [29] | Significant Increase (p ≈ 0.001 for 0% vs. 10%) [29] | No significant impact (p ≈ 0.08) [29] |

| Waiting Time (τ) | No significant post-hoc difference [29] | No significant impact (p ≈ 0.19) [29] | No significant post-hoc difference [29] | Significant Increase (p ≈ 0.02 for 0 min vs. 120 min) [29] |

Expected Results and Analysis

Successful encapsulation will yield GUVs visible via phase-contrast microscopy. When fluorescently labeled actin is used, confocal microscopy will reveal its distribution inside the GUVs. In the presence of MgCl₂ and the ion carrier, F-actin will accumulate near the GUV membrane, leading to a measurable change in the vesicle's mechanical properties [17]. The functionality of encapsulated actin-binding proteins can be assessed by their ability to cross-link, bundle, or sever the actin network, observable as distinct morphological changes in the actin architecture within the GUVs.

Mechanical Property Assessment

The mechanical effect of encapsulated actin can be quantified by analyzing vesicle deformability.

As illustrated, GUVs containing polymerized F-actin will show significantly increased resistance to deformation compared to those containing only monomeric G-actin or empty GUVs, confirming the mechanical reinforcement provided by the actin cortex [17].

Application Notes

- Troubleshooting: Low GUV yield can often be remedied by increasing the chloroform percentage (Δ) in the lipid-dispersed oil and ensuring a sufficient waiting time (τ) for monolayer maturation [29].

- Actin Polymerization Control: The use of an ion carrier is crucial for initiating actin polymerization from within the GUVs, as Mg²⁺ ions cannot passively cross the lipid bilayer efficiently [17].

- Composition Flexibility: This protocol can be adapted for various lipid compositions, including charged lipids, and for co-encapsulating other proteins or biomolecules to reconstruct more complex cytoskeletal processes [29] [30].

The construction of biomimetic membranes that replicate the fluidity and stability of natural cell membranes is a cornerstone of synthetic biology research, particularly in the context of building minimal cells from giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs). A primary challenge in this field is the successful encapsulation and interaction of actin networks with the lipid bilayer, a process essential for reconstituting cell-like behaviors such as shape changes, motility, and division [19]. The lipid composition of the bilayer directly governs its physical properties, including phase separation, fluidity, and mechanical stability, which in turn orchestrate the spatial organization and dynamic remodeling of the encapsulated cytoskeleton [19] [18]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and compositional guidelines to optimize GUV lipid bilayers for studies focusing on actin encapsulation and membrane-cytoskeleton interactions.

Lipid Composition and Membrane Properties

The careful selection of lipid species is paramount for controlling membrane behavior. Ternary mixtures containing phospholipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol are widely used to induce liquid-ordered (Lo) and liquid-disordered (Ld) phase coexistence, mimicking the lipid raft heterogeneity of the native plasma membrane [31] [19].

Quantitative Effect of Lipid Composition on Membrane Fluidity

Membrane fluidity can be quantitatively assessed by measuring the translational diffusion coefficient (Dₜ) of lipid probes. The table below summarizes how different lipid compositions and phases influence the diffusion of a Bodipy-labeled cholesterol analog (Bdp-Chol) [31].

Table 1: Translational Diffusion of a Lipid Probe in Different Membrane Environments

| Lipid Phase/Composition | Translational Diffusion Coefficient, Dₜ (×10⁻⁸ cm²/s) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Disordered (Ld) Phase | ( 7.4 \pm 0.3 ) | Formed by unsaturated lipids like DOPC; high fluidity. |

| Liquid-Ordered (Lo) Phase | ( 5.0 \pm 0.2 ) | Cholesterol-rich with sphingomyelin; lower fluidity, biologically relevant. |

| DOPC/Cholesterol/SM (25/50/25) | Lo: ( 5.0 \pm 0.2 ) (Bdp-Chol) | Preferential partitioning of Bdp-Chol into the Lo phase (Kp=1.88). |

Compositions for Phase Separation and Actin Encapsulation

Specific lipid molar ratios have been successfully employed to generate phase-separated GUVs that also support the encapsulation and polymerization of actin networks. The following table outlines two validated compositions [18].

Table 2: Optimized Lipid Compositions for Phase-Separated GUVs with Actin Encapsulation

| Lipid Components | Composition 1: Actin Bundles (mol %) | Composition 2: Actin Networks (mol %) | Function of Lipid Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC (Dioleoylphosphatidylcholine) | 17.5 | 33.5 (DOPC+DOPG) | Unsaturated lipid, forms Ld phase [19]. |

| DPPC (Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine) | 31.5 | 30 | Saturated lipid, contributes to Lo phase formation. |

| Cholesterol | 30 | 30 | Regulates membrane fluidity and promotes Lo phase [31] [19]. |

| Biotinyl CAP PE | 1 | 1.5 | Provides binding sites for streptavidin-linked proteins (e.g., NPFs). |

| DOPG/DPPG | 21 (DOPG+DPPG) | - | Anionic lipids, can influence protein binding via charge interactions. |

| Texas-Red DHPE / Atto655-DOPE | Trace (0.001 mol%) | Trace (0.001 mol%) | Fluorescent labels for membrane visualization. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: One-Pot Emulsion Transfer for Actin Encapsulation in Phase-Separated GUVs

This protocol is adapted for high encapsulation efficiency while maintaining the activity of cytoskeletal proteins [18].

Materials:

- Lipids: DOPC, DPPC, Cholesterol, DOPG, DPPG, Biotinyl CAP PE, Atto655-DOPE (or Texas-Red DHPE).

- Proteins: G-actin (unlabeled, Atto488-labeled, biotinylated).

- Buffers and Reagents: Chloroform, decane, mineral oil, Ficoll70, BSA, GTP (for FtsZ), Tris-HCl, sucrose, KCl, MgCl₂, DTT, ATP.

- Equipment: Bath sonicator, centrifuge, vacuum desiccator, glass vials, 96-well imaging plates.

Procedure:

- Lipid Mixture Preparation: a. In a glass vial, combine lipids in chloroform to achieve Composition 1 or 2 from Table 2. b. Evaporate the chloroform under a stream of N₂ gas to form a thin lipid film. c. Place the vial under vacuum in a desiccator for 30 minutes to remove residual solvent. d. Re-disperse the dried lipid film in a mixture of decane and mineral oil. e. Sonicate the lipid-in-oil mixture at ~50°C for 30 minutes and incubate at 37°C before use.

Inner Solution Preparation (Actin Bundle Mixture): a. Prepare a 10 µL actin master mix on ice, protected from light, containing: - 86% G-actin - 10% Atto488-actin - 4% biotinylated actin b. The final concentration of the actin mix in the encapsulation solution should be approximately 35 µM.

GUV Formation via Emulsion Transfer: a. Gently layer the protein-containing inner solution (from step 2) on top of the prepared lipid-in-oil mix. b. Centrifuge the tube at elevated temperatures (optimized at 37°C to promote phase separation while retaining protein activity). c. After centrifugation, collect the formed GUVs from the bottom of the tube for immediate imaging or further experimentation.

Diagram 1: Emulsion transfer workflow for GUV production.

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Platform for Actin-Based Membrane Remodeling Studies

This protocol is designed for high-throughput, sequential observation of actin-induced membrane remodeling on immobilized GUVs [19].

Materials:

- Microfluidic Chips: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chambers.

- Passivation Reagents: PLL-PEG to prevent protein and lipid adsorption.

- Actin Polymerization Components: Actin, Arp2/3 complex, profilin, capping protein (CP), streptavidin-pVCA-His (SpVCA-His).

- Buffers: Polymerization buffer (sucrose, Tris, KCl, MgCl₂, DTT, ATP, β-casein).

Procedure:

- Microfluidic Chamber Preparation: a. Treat PDMS microfluidic chambers with PLL-PEG to create a non-adhesive surface. b. Load the passivated chamber with a population of pre-formed, biotinylated GUVs. c. Immobilize dozens of GUVs in designated traps within the chamber.

Actin Network Assembly: a. Flush the chamber with a solution containing the actin polymerization machinery: SpVCA-His (binds to biotinylated lipids), actin, Arp2/3 complex, profilin, and CP. b. Incubate to allow the formation of a branched actin network on the inner or outer surface of the GUVs. c. The actin shell generates compressive forces, leading to symmetry breaking and polarization, which can propel the GUVs in a manner reminiscent of Listeria monocytogenes.

Observation and Analysis: a. Monitor the dynamics of membrane deformation and the concurrent stabilization of lipid domains by the actin network in real-time. b. The platform allows for the sequential modification of the protein composition to dissect the roles of individual factors.

Diagram 2: Microfluidic assay for actin remodeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for GUV-Actin Reconstitution Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|