Cellular Mechanotransduction: Decoding Cytoskeletal Signaling Pathways in Health and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals through the cytoskeleton.

Cellular Mechanotransduction: Decoding Cytoskeletal Signaling Pathways in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals through the cytoskeleton. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the core mechanosensors, transducers, and signaling cascades, with a focus on pathways involving integrins, Rho GTPases, and Hippo/YAP. It further examines advanced methodological approaches for studying these processes, discusses common experimental challenges and solutions, validates key pathways across different physiological and pathological contexts, and highlights emerging therapeutic targets in fibrosis, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. The synthesis of foundational principles with cutting-edge applications offers a vital resource for innovating mechano-based therapeutic strategies.

The Molecular Machinery of Cellular Mechanosensing: From Force Detection to Biochemical Signal

Mechanotransduction—the process by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals—is a fundamental biological process essential for physiology and disease pathogenesis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three core mechanosensor systems: Integrins and Focal Adhesion Complexes, Piezo ion channels, and TRPV ion channels. We detail their distinct structural properties, activation mechanisms, and downstream signaling pathways, synthesizing current research to guide drug development and basic science. The content is framed within the broader context of cytoskeleton signaling research, offering structured quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visual signaling pathways to serve as a resource for researchers and scientists in the field.

In complex biological microenvironments, cells are constantly subjected to mechanical forces, including tensile stress, compression, fluid shear stress, and alterations in extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness [1] [2]. The process of mechanotransduction allows cells to perceive these extracellular mechanical cues and transduce them into intracellular biochemical responses, thereby regulating critical cellular activities such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, and gene expression [3] [4]. This process is mediated by specialized mechanosensitive entities, primarily integrin-based focal adhesion complexes and mechanosensitive ion channels such as Piezo and Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid (TRPV) families [1] [4]. These sensors act as the primary interfaces for mechanical signal detection, initiating a cascade of events that often culminates in cytoskeletal remodeling and nuclear transcription [4]. The mechanotransduction signaling pathways are crucial for tissue development, homeostasis, and the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, including fibrosis, cardiomyopathy, osteoporosis, and cancer [1] [3] [5]. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular machinery of these core mechanosensors is therefore imperative for advancing fundamental research and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Core Mechanosensors: Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling

Integrins and Focal Adhesion Complexes

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, composed of α and β subunits, that serve as a primary mechanical link between the ECM and the intracellular actin cytoskeleton [3] [4]. They exist in three conformational states: an inactive bent state, an intermediate extended state, and a fully activated state with a high affinity for ligands [4]. Mechanical forces induce a conformational shift to the activated state, enabling integrins to bind ECM components such as fibronectin and collagen. This binding triggers integrin clustering and the recruitment of a dense plaque of signaling proteins, forming a focal adhesion (FA) complex [3].

The core proteins within FAs include talin, which directly binds integrin cytoplasmic tails and actin; vinculin, which is recruited upon force-induced unfolding of talin to stabilize the adhesion; focal adhesion kinase (FAK); and c-Src kinase [3] [4]. The FA acts as a dynamic mechanosensory hub. Upon mechanical stimulation, FAK autophosphorylates at Tyr397, creating a binding site for Src and initiating downstream signaling cascades such as the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, which regulate cell proliferation, survival, and migration [3]. Furthermore, the integrin-FA axis is a key regulator of the RhoA/ROCK pathway, controlling actomyosin contractility and cytoskeletal tension [3]. This complex also facilitates the nuclear shuttling of transcriptional coactivators like YAP/TAZ, thereby translating mechanical cues into gene expression programs [4].

Table 1: Key Components of the Integrin-Focal Adhesion Mechanosensing Complex

| Component | Structure/Type | Key Function in Mechanotransduction | Representative Downstream Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin | αβ heterodimer (24 types) | Principal receptor for ECM; senses stiffness and force | Talin, FAK, Src |

| Talin | Cytoskeletal linker | Binds integrin β-tail; links to F-actin; unfolds under force to expose vinculin-binding sites | Vinculin, RIAM, PIPKIγ |

| Vinculin | Cytoskeletal linker | Binds unfolded talin; reinforces adhesion structure; transmits cytoskeletal tension | F-actin, α-actinin, paxillin |

| FAK | Cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase | Autophosphorylates at Y397 upon integrin activation; initiates scaffolding & signaling | Src, PI3K, Grb2-SOS (MAPK pathway) |

| c-Src | Cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase | Binds pY397-FAK; phosphorylates substrates like p130Cas | p130Cas, FAK, paxillin |

Piezo Ion Channels

The Piezo family, comprising Piezo1 and Piezo2, represents a major class of mechanically gated, non-selective cation channels [6] [7]. Piezo1, the more ubiquitously expressed member, is a massive trimeric protein with a unique three-bladed propeller structure that curves the plasma membrane into a distinctive nano-bowl shape [4] [7]. Two primary models describe its activation: the "force-from-lipid" model, where membrane tension directly induces conformational changes in the channel, flattening the nano-bowl and opening the pore; and the "force-from-filament" model, where the channel is gated via mechanical tethering to intracellular cytoskeletal components through proteins like E-cadherin/β-catenin/vinculin [4] [6].

Upon activation by mechanical stimuli such as shear stress or membrane stretch, Piezo1 channels open to permit a rapid influx of cations, particularly Ca²⁺ [4] [7]. This Ca²⁺ surge acts as a critical second messenger, activating various signaling pathways. These include the calmodulin/CaMKII pathway, which influences gene expression and cell migration, and the YAP/TAZ pathway, which promotes pro-growth and proliferative transcriptional programs [4] [7]. Piezo1 is notably upregulated in pathological conditions involving altered mechanics, such as glioblastoma, where its activity contributes to tumor progression, angiogenesis, and immune evasion [7].

Table 2: Properties of Major Mechanosensitive Ion Channels

| Channel | Family | Ion Selectivity | Primary Gating Mechanism | Key Physiological Roles | Pathological Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezo1 | Piezo | Cation non-selective (Ca²⁺) | Membrane tension ("Force-from-lipid"), Tethered forces ("Force-from-filament") | Vascular development, Erythrocyte volume regulation, Touch sensation | Glioblastoma progression, Cancer metastasis, Xerocytosis |

| TRPV4 | Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid | Cation non-selective (Ca²⁺) | Osmolarity, Shear stress, Phorbol esters | Osmoregulation, Blood flow regulation, Bone remodeling | Neuropathy, Skeletal dysplasias, Pulmonary edema |

TRPV Ion Channels

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is another key mechanosensitive cation channel implicated in sensing diverse mechanical and chemical stimuli, including osmotic pressure, shear stress, and matrix stiffness [4]. While its precise mechanogating mechanism is less defined than Piezo's, it is believed to be activated through direct membrane tension and interactions with the cytoskeleton. TRPV4 activation also results in Ca²⁺ influx, leading to the activation of Ca²⁺-dependent enzymes and signaling pathways that regulate cellular volume, vascular tone, and bone homeostasis [4]. Importantly, TRPV4 often functions in concert with other mechanosensors; for instance, it can cooperate with Piezo1 and the YAP/TAZ signaling axis to achieve mechanical programming of gene expression [4]. Dysregulation of TRPV4 is linked to a spectrum of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, skeletal dysplasias, and pulmonary edema.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Mechanosensors

Probing Integrin-Mediated Mechanotransduction

Protocol Title: Analyzing Integrin Activation and Focal Adhesion Kinetics in Response to Substrate Stiffness.

Objective: To quantify the recruitment and phosphorylation dynamics of FA proteins in cells plated on ECM-functionalized hydrogels with tunable stiffness.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- PDMS Hydrogels or Polyacrylamide Gels: Functionalized with collagen I (50 µg/mL) or fibronectin (10 µg/mL) to mimic the ECM [3] [4].

- Specific Antibodies: Anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr397) for activation status, anti-vinculin for visualizing adhesion structures, and anti-integrin β1 (clone 9EG7) for detecting activated integrin conformations [3] [4].

- Inhibitors: FAK inhibitor PF-562271 (1 µM) or Src inhibitor PP2 (10 µM) to disrupt specific signaling nodes [3].

Methodology:

- Cell Plating and Stimulation: Plate fibroblasts (e.g., NIH/3T3) or mesenchymal stem cells onto soft (∼1 kPa) and stiff (∼50 kPa) hydrogels. Allow cells to adhere and spread for 4-6 hours.

- Immunofluorescence and Imaging: Fix, permeabilize, and stain cells for p-FAK (Y397), vinculin, and F-actin (using phalloidin). Acquire high-resolution confocal images.

- Quantitative Image Analysis: Use software like ImageJ or MetaMorph to quantify:

- Focal Adhesion Size and Number: Threshold and analyze vinculin-positive patches.

- FAK Phosphorylation Intensity: Measure mean fluorescence intensity of p-FAK staining at adhesion sites.

- Nuclear Translocation of YAP: Stain for YAP and calculate the nucleus/cytoplasm fluorescence intensity ratio as a readout of integrated mechanotransduction output [4].

- Biochemical Validation: Perform western blotting on cell lysates from the same conditions using antibodies against p-FAK, total FAK, and YAP/TAZ target genes (e.g., CTGF).

Functional Characterization of Piezo1 Channels

Protocol Title: Assessing Piezo1 Activity Using Calcium Imaging and Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology.

Objective: To directly measure Piezo1-mediated cation currents and intracellular Ca²⁺ flux in response to controlled mechanical stimuli.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Piezo1 Agonists/Antagonists: Yoda1 (agonist, 10-30 µM) and GsMTx4 (inhibitory tarantula peptide, 1-5 µM) [7].

- Calcium-Sensitive Dyes: Fura-2 AM or Fluo-4 AM (2-5 µM) for ratiometric or intensity-based Ca²⁺ imaging.

- Patch-Clamp Setup: Equipped with a pressure control system for applying precise negative pressure (suction) to the patched membrane.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Use a Piezo1-overexpressing cell line (e.g., HEK293T) or a relevant primary cell type (e.g., vascular endothelial cells).

- Calcium Imaging:

- Load cells with Fura-2 AM dye for 30-45 minutes at 37°C.

- Place cells in a perfusion chamber and establish a baseline. Apply mechanical stimuli: (a) Shear Stress using a perfusion system (5-20 dyne/cm²), or (b) Chemical Agonist by perfusing Yoda1.

- Monitor the Fura-2 emission ratio (340/380 nm excitation). A rapid increase in ratio indicates Ca²⁺ influx. Pre-treat with GsMTx4 to confirm Piezo1-specific responses.

- Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology:

- Establish a whole-cell patch configuration.

- Apply a series of stepped negative pressures (e.g., -10 to -50 mmHg) to the pipette to mechanically stimulate the membrane.

- Record the resulting inward cationic currents. Piezo1 currents are characterized by rapid activation and inactivation upon sustained pressure.

- Repeat the pressure protocol in the presence of GsMTx4 to inhibit and confirm Piezo1-mediated currents.

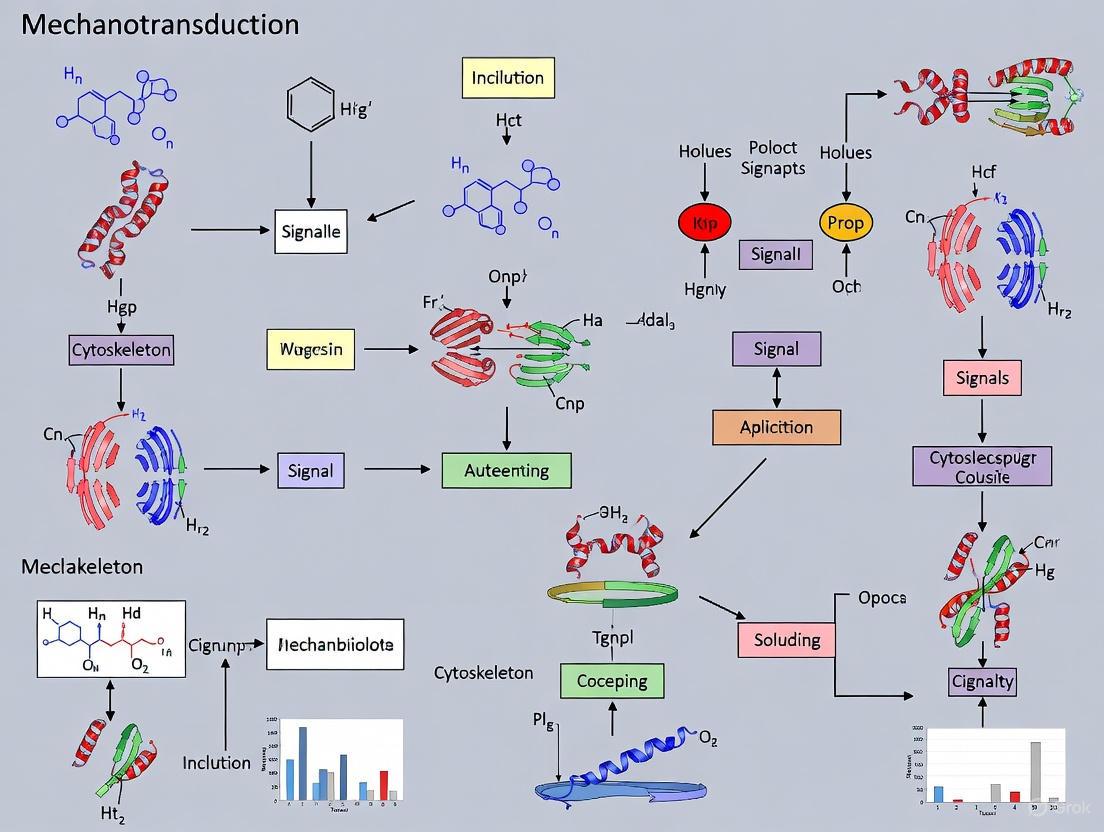

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Integrin-FAK Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade initiated by integrin-mediated mechanotransduction.

Diagram Title: Integrin-FAK Mechanotransduction Pathway

Piezo1 Mechanosignaling Pathway

The following diagram outlines the key signaling events triggered by Piezo1 channel activation.

Diagram Title: Piezo1 Channel Signaling Cascade

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mechanosensor Research

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Specific Example | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunable Hydrogels | Biomaterial | Polyacrylamide, PDMS | To create substrates of defined stiffness (e.g., 1-50 kPa) for studying cell response to ECM mechanics. |

| Mechano-Agonists | Small Molecule/Peptide | Yoda1 (Piezo1), GsMTx4 (Inhibitor) | To chemically activate or inhibit mechanosensitive ion channels for functional studies. |

| Activation-State Antibodies | Biochemical Probe | Anti-integrin β1 (Clone 9EG7), Anti-pFAK (Y397) | To detect active conformations of integrins or phosphorylation of FA proteins via IF/WB. |

| Biosensor Cell Lines | Genetic Model | YAP/TAZ Localization Reporters, FRET-based tension sensors | To visualize downstream signaling activity or molecular-scale forces in live cells. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Equipment | N/A | To quantitatively measure the nanoscale stiffness of cells and tissues. |

The core mechanosensors—integrin-based focal adhesions, Piezo channels, and TRPV channels—constitute an integrated cellular network for perceiving and responding to mechanical cues. While each system has unique structural and activation characteristics, their signaling pathways are highly interconnected, often converging on key regulators like the cytoskeleton and transcriptional coactivators YAP/TAZ. Continued elucidation of these mechanisms, aided by the experimental tools and methodologies detailed herein, is vital for unraveling their roles in physiology and disease. Targeting these mechanosensors holds significant, yet largely untapped, potential for therapeutic intervention in pathologies ranging from fibrosis and osteoporosis to cancer.

The cytoskeleton, comprising actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, extends beyond its classical role as a structural scaffold to function as a dynamic, integrated network essential for cellular mechanotransduction. This whitepaper delineates the distinct mechanical properties and collaborative functions of these filament systems in sensing, transmitting, and responding to mechanical cues. We synthesize current mechanistic insights into how force is biochemically encoded via pathways such as Rho/ROCK and YAP/TAZ, and how this signaling directs cell fate decisions. Supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies, this review provides a framework for researchers and drug development professionals targeting cytoskeletal mechanobiology in therapeutic contexts.

Cellular mechanotransduction—the conversion of mechanical signals into biochemical responses—is a fundamental process governing embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and disease progression [8]. The cytoskeleton serves as the central mediator of this process, acting as both a mechanical sensor and a transmitter of force [9]. Composed of three primary filament systems—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—this dynamic infrastructure continually remodels to accommodate and respond to external physical cues from the extracellular matrix (ECM) and neighboring cells [9] [8].

The significance of cytoskeletal force transmission is particularly evident in pathologies such as fibrosis, cancer, and immunodeficiency, where aberrant mechanical signaling disrupts normal cellular function [1] [10] [8]. This whitepaper examines the unique biophysical properties of each filament type, their integrated role in force transmission, the key signaling pathways they activate, and practical experimental approaches for investigating cytoskeletal mechanobiology.

Architectural and Mechanical Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

The three cytoskeletal filaments form distinct yet interconnected networks with specialized mechanical roles, allowing cells to withstand diverse physical challenges while maintaining the structural integrity required for force transmission.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Cytoskeletal Filaments

| Property | Actin Filaments | Microtubules | Intermediate Filaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~7 nm [11] | ~25 nm (outer) [12] | ~10 nm [12] |

| Structure | Two-stranded helix [12] | Hollow cylinder [12] | Rope-like, coiled-coil bundles [13] [12] |

| Polarity | Yes (barbed/pointed ends) [11] | Yes (plus/minus ends) [12] | Non-polar [12] |

| Mechanical Role | Tension-bearing [12] | Compression resistance [12] | Extensibility, tensile strength [13] [12] |

| Key Mechanical Property | Contractility via actomyosin | High bending rigidity | High elastic deformation (>x original length) [12] |

Actin Filaments: Masters of Tension and Contraction

Actin filaments (F-actin) are dynamic polymers of globular actin (G-actin) that generate force through polymerization at the barbed end and controlled disassembly. Their organization into structures like the perinuclear actin cap and stress fibers is crucial for transmitting tension from the ECM to the nucleus, influencing nuclear shape and gene expression [9]. This contractile capacity is primarily driven by myosin II motor proteins, which pull on actin filaments to generate tension [10].

Microtubules: Compressive Struts and Intracellular Highways

Microtubules are stiff, hollow polymers of α/β-tubulin dimers that radiate from the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) [12]. Their rigidity allows them to resist compressive forces [12]. They serve as primary tracks for intracellular transport, with motor proteins like kinesins and dyneins moving cargo along them, which is vital for distributing signaling molecules during mechanotransduction [9] [12].

Intermediate Filaments: Elastic and Integrative Networks

Intermediate filaments (IFs), including keratins and vimentin, are non-polar, flexible proteins that assemble into rope-like networks [13] [12]. Unlike actin and microtubules, IFs lack motor proteins but possess a unique ability to undergo large deformations without breaking, providing cells with exceptional mechanical resilience [12]. They form a cage around the nucleus and connect to cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions, integrating mechanical signals across the entire cell [13].

Integrated Force Transmission from Extracellular Matrix to Nucleus

The cytoskeleton forms a continuous physical link—a mechanotransduction highway—that allows forces originating outside the cell to directly alter nuclear structure and chromatin organization. This pathway involves several key structures:

- Focal Adhesions (FAs): Macromolecular complexes where transmembrane integrins connect the ECM to the intracellular actin cytoskeleton, serving as primary mechanosensing sites [9].

- Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) Complex: A nuclear envelope-spanning complex that physically couples the cytoskeleton to the nuclear lamina, transmitting cytoskeletal forces directly to the nucleus [9].

- Nuclear Lamina: A meshwork of lamin intermediate filaments underlying the inner nuclear membrane that provides structural support and mediates chromatin tethering, directly influencing gene expression in response to force [9].

Force transmission follows a defined pathway: ECM → FAs (integrins) → actin stress fibers (often contractile) → LINC complex → nuclear lamina → chromatin [9]. This direct physical connection allows mechanical perturbations to rapidly induce biochemical changes within the nucleus, ultimately influencing cell fate decisions in processes like stem cell differentiation and cellular reprogramming [9].

Key Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathways

The mechanical signals transmitted through the cytoskeleton activate several conserved biochemical pathways that regulate gene expression and cell behavior.

Diagram 1: Core mechanotransduction signaling from force to gene expression.

Rho/ROCK Pathway: Regulating Actomyosin Contractility

The RhoA/ROCK pathway is a central regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, particularly actomyosin-based contractility. In response to mechanical stimuli, RhoA activation stimulates ROCK, which subsequently phosphorylates and activates myosin light chain (MLC), enhancing myosin II's motor activity and its ability to cross-link and contract actin filaments [8]. This increased contractility reinforces stress fibers and elevates intracellular tension, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies the mechanical signal. This pathway is critical for processes ranging from T cell immunological synapse maturation to fibroblast activation in fibrosis [10] [8].

YAP/TAZ Pathway: Nuclear Mechanotransducers

YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif) are key transcriptional co-activators that shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus in response to mechanical cues [9] [8]. In cells experiencing low mechanical tension or on soft substrates, YAP/TAZ are phosphorylated and retained in the cytoplasm. High cytoskeletal tension, typically driven by actin stress fibers and the perinuclear actin cap, promotes their nuclear localization [9]. Once in the nucleus, YAP/TAZ associate with transcription factors to drive expression of genes controlling proliferation, differentiation, and survival, thereby translating mechanical signals into long-term cell fate decisions [9] [8].

Ion Channel Activation: Rapid Mechanoelectrical Coupling

Mechanosensitive ion channels, such as Piezo and TRPV families, provide a rapid response mechanism to mechanical force. These channels are directly gated by membrane tension or cytoskeletal forces, allowing cations like Ca²⁺ to enter the cell upon activation [1] [8]. The ensuing Ca²⁺ influx triggers myriad downstream signaling events, including cytoskeletal remodeling and activation of kinases. For example, in intervertebral disc degeneration, abnormal mechanical loading activates Piezo channels in nucleus pulposus cells, initiating a cascade that leads to cell death and ECM degradation [1].

Experimental Protocols for Cytoskeletal Mechanobiology

Investigating cytoskeletal force transmission requires specialized methodologies that probe both structure and function.

Quantifying Cytoskeletal Organization and Dynamics

Protocol: Fluorescence Microscopy and Live-Cell Imaging

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells on functionalized glass-bottom dishes or on substrates of tunable stiffness (e.g., polyacrylamide hydrogels).

- Staining: Fix cells and stain F-actin with phalloidin conjugates (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin). For microtubules, use anti-α-tubulin antibodies. For live-cell imaging, transfert cells with GFP-LifeAct or GFP-tubulin.

- Image Acquisition: Use confocal or TIRF microscopy. For live imaging, acquire time-lapse images every 5-10 seconds to track filament dynamics.

- Analysis: Quantify fluorescence intensity, filament orientation (using FibrilTool in ImageJ), and network morphology. For live imaging, analyze treadmilling rates or microtubule dynamic instability parameters (growth/shrinkage rates, catastrophe frequency).

Protocol: Traction Force Microscopy (TFM)

- Substrate Preparation: Fabricate polyacrylamide hydrogels of defined stiffness (e.g., 1-50 kPa) embedded with fluorescent microbeads.

- Cell Seeding and Imaging: Seed cells onto the substrate and acquire images of the bead layer with the cell present and after cell detachment (trypsinization).

- Force Calculation: Compute the displacement field of the beads between the two images. Use Fourier Transform Traction Cytometry or Bayesian methods to calculate the tractions exerted by the cell on the substrate.

Modulating Cytoskeletal Dynamics with Pharmacological Agents

- Protocol: Using Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators

- Principle: Utilize specific biochemical agents to perturb cytoskeletal dynamics and observe functional outcomes.

- Sample Reagents and Applications:

- Cytoskeletal Polymerization/Stability: Latrunculin A (actin depolymerizer), Jasplakinolide (actin stabilizer), Nocodazole (microtubule depolymerizer), Taxol (microtubule stabilizer) [9].

- Myosin II Contractility: Blebbistatin (specific myosin II inhibitor) [10].

- Rho/ROCK Signaling: Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) [9] [8].

- Methodology: Treat cells with optimized concentrations of the agent and assess subsequent changes in morphology, signaling (e.g., YAP/TAZ localization via immunofluorescence), or gene expression (e.g., qPCR for YAP/TAZ targets like CTGF).

Table 2: Research Reagent Toolkit for Cytoskeletal Mechanobiology

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin Polymerization Inhibitor | Latrunculin A, Cytochalasin D | Binds G-actin / caps barbed ends | Disrupts actin network to test its necessity in mechanosensing [9]. |

| Microtubule Stabilizer | Taxol (Paclitaxel) | Suppresses microtubule dynamics | Tests the role of microtubule turnover in intracellular transport and force distribution [9]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Y-27632 | Inhibits ROCK kinase activity | Probes the role of Rho/ROCK-mediated actomyosin contractility in signaling [9] [8]. |

| Myosin II Inhibitor | Blebbistatin | Specifically inhibits non-muscle myosin IIA | Reduces cellular tension to study its impact on YAP/TAZ localization and FA maturation [10]. |

| Tension Probes | FRET-based biosensors | Reports molecular-level force | Visualizes piconewton forces across specific proteins (e.g., in FAs) in live cells. |

| Stiffness-Tunable Substrates | Polyacrylamide hydrogels | Mimics a range of tissue stiffness | Investigates how substrate mechanics direct stem cell differentiation or tumor cell invasion [9] [8]. |

The cytoskeleton functions as a dynamic, information-processing network that is fundamental to cellular mechanotransduction. Its individual components—actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments—perform distinct yet synergistic mechanical roles, enabling cells to sense, integrate, and respond to physical cues from their microenvironment. Key signaling pathways, including Rho/ROCK and YAP/TAZ, translate these cytoskeletal dynamics into decisive changes in cell fate and function.

Future research will focus on deepening our understanding of the phosphoinositide (PIPn) signaling system that spatially and temporally controls cytoskeletal remodeling [11], and the role of the nuclear cytoskeleton in directly regulating transcription. From a therapeutic perspective, targeting cytoskeletal dynamics or specific mechanosensitive elements like Piezo channels holds significant promise for treating diseases driven by mechanical dysfunction, such as fibrosis, cancer, and degenerative disorders. The continued development of high-resolution force probes and biomimetic synthetic scaffolds will be crucial for advancing this frontier.

Mechanotransduction, the process by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals, is fundamental to cellular homeostasis, development, and disease progression. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core signaling pathways—Rho GTPase, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt—that serve as crucial mechanotransduction hubs. We synthesize current understanding of their molecular mechanisms, regulatory functions, and crosstalk, with a specific focus on their role in cytoskeletal reorganization and cellular adaptation to mechanical stress. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this review integrates quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools to support ongoing research in mechanobiology and the development of novel mechanotherapeutics.

Cellular mechanotransduction is a critical biological process whereby mechanical cues—including hydrostatic pressure, fluid shear stress, tensile force, and extracellular matrix stiffness—are converted into intracellular biochemical signals that regulate diverse functions from embryonic development to disease pathogenesis [8]. These mechanical signals are sensed by various cellular structures and transmitted through sophisticated signaling networks to orchestrate appropriate cellular responses such as cytoskeletal remodeling, gene expression changes, and alterations in cell metabolism [14] [8]. Among the numerous signaling pathways involved, the Rho GTPase family, MAPK cascades, and PI3K/Akt pathway have emerged as central regulators of mechanotransduction, each with distinct yet interconnected functions. These pathways collectively regulate fundamental cellular processes including morphogenesis, polarity, movement, cell division, and gene expression through complex crosstalk and feedback mechanisms [15] [8]. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms by which these pathways mediate mechanotransduction is essential for deciphering their roles in physiological and pathological contexts, particularly in mechanically active tissues and solid tumors where these pathways are frequently dysregulated.

Rho GTPase Pathway in Mechanotransduction

Molecular Mechanism and Regulation

The Rho family GTPases function as molecular switches that cycle between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states, thereby controlling signal transduction in response to mechanical stimuli [15]. This cycling is regulated by three classes of proteins: guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote GTP loading and activation, GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) that stimulate GTP hydrolysis and inactivation, and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) that control membrane-cytosol cycling [15]. The human genome encodes approximately 20 canonical RHO GTPases, 85 GEFs, and 66 GAPs, highlighting the complexity and specificity of regulatory control [15]. Mechanical stimulation activates Rho GTPases through mechanosensitive receptors including integrins, which transmit extracellular mechanical signals via intracellular kinase networks [16].

Rho proteins contain a conserved G domain for nucleotide binding and a C-terminal hypervariable region (HVR) ending with a CAAX motif that undergoes posttranslational modifications—isoprenylation, endoproteolysis, and carboxyl methylation—critical for membrane association and biological activity [15]. The transition between inactive and active states involves structural rearrangement in two regions known as switch I (G2) and switch II (G3), which create binding platforms for downstream effectors when GTP-bound [15].

Key Rho GTPases and Their Functions

- RhoA: Primarily regulates actomyosin contractility through its downstream effectors ROCK I/II, which phosphorylate myosin light chain (MLC) directly and indirectly by inhibiting myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) [15] [17]. This pathway promotes stress fiber formation and cellular tension generation critical for mechanotransduction.

- Rac1: Controls lamellipodia formation and membrane ruffling through effectors including WAVE and PAK1/2/3, facilitating cell spreading and migration in response to mechanical cues [15] [17].

- Cdc42: Governs filopodia formation and cell polarity via effectors such as N-WASP and PAK4, enabling directional sensing and response to mechanical gradients [15] [17].

Table 1: Major Rho GTPase Family Members and Their Functions in Mechanotransduction

| GTPase | Key Effectors | Cellular Function | Role in Mechanotransduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhoA | ROCK I/II, DIA1/2 | Stress fiber formation, actomyosin contraction | Cellular contractility, tension sensing |

| Rac1 | PAK1/2/3, WAVE | Lamellipodia formation, membrane ruffling | Cell spreading, migration |

| Cdc42 | N-WASP, PAK4 | Filopodia formation, cell polarity | Directional sensing, structural adaptation |

| Rnd3 | Socius, ROCK1 | Loss of stress fibers | Modulation of cellular stiffness |

| RhoG | Kinectin | Microtubule-dependent transport | Intracellular trafficking in response to stress |

Downstream Signaling and Cytoskeletal Reorganization

The Rho GTPases exert precise control over cytoskeletal dynamics through their downstream effectors. Activated RhoA/ROCK signaling increases phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC), enhancing actomyosin contractility [17]. This contractile force generation is essential for cells to sense and respond to mechanical properties of their environment. Additionally, Rho GTPases regulate focal adhesion dynamics through integrin-mediated signaling, with activated Rac1 and Cdc42 promoting focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylation and recruitment of structural proteins like paxillin to focal adhesion complexes [17]. The WASP family proteins, particularly WAVE downstream of Rac and N-WASP downstream of Cdc42, activate the Arp2/3 complex to nucleate actin branching, enabling rapid cytoskeletal remodeling in response to mechanical stimuli [17].

MAPK Pathway in Mechanotransduction

Pathway Activation and Quantitative Relationship to Mechanical Stress

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway serves as a key mechanotransduction signaling module that demonstrates a quantitative relationship with mechanical tension. Research using skeletal muscle models has revealed that MAPK phosphorylation directly correlates with the magnitude of mechanical stress, with eccentric contractions generating the highest tension producing the greatest MAPK activation, followed by isometric and concentric contractions [18]. Specifically, phosphorylation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) isoforms exhibits a strong linear relationship with peak tension over a 15-fold tension range (r² = 0.89), establishing MAPK activation as a quantitative reflection of applied mechanical stress [18]. This tension-dependent activation pattern suggests different roles for JNK and ERK MAPKs in mechanically induced signaling, with variations in maximal response amplitude and sensitivity to mechanical stimuli.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mechanical Activation

Mechanical activation of MAPK pathways occurs through multiple mechanosensitive elements. The mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 responds to hydrostatic pressure and other mechanical stimuli to activate MAPK signaling cascades, including p38 pathways [8]. Additionally, integrin-mediated mechanosensing and cytoskeletal rearrangements contribute to MAPK activation through scaffolding proteins and adapter molecules that facilitate signal transduction from mechanical sensors to kinase cascades. Once activated, MAPKs translocate to the nucleus where they phosphorylate transcription factors such as c-Jun and ATF2, leading to altered gene expression patterns that support cellular adaptation to mechanical stress [18].

Table 2: MAPK Isoforms in Mechanotransduction

| MAPK Family | Activation Stimulus | Key Transcription Factors | Cellular Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| JNK (p54) | Peak tension (eccentric > isometric > concentric) | c-Jun, ATF2 | Gene expression regulation, hypertrophy |

| ERK | Tension-dependent phosphorylation | Elk-1, c-Myc | Proliferation, differentiation |

| p38 | Hydrostatic pressure, osmotic stress | ATF2, MEF2 | Inflammation, stress response, differentiation |

Functional Outcomes in Mechanotransduction

MAPK signaling in response to mechanical stimuli regulates critical cellular processes including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. In skeletal muscle, MAPK activation serves as a crucial mediator of mechanically induced hypertrophy, providing a molecular link between mechanical loading and adaptive tissue remodeling [18]. The pathway also contributes to pathological processes when dysregulated; for instance, in fibroblasts, mechanical strain promotes proliferation through p38 MAPK cascades [8]. The differential sensitivity and activation kinetics of various MAPK isoforms enable cells to decode complex mechanical information into specific biochemical responses appropriate for the type, magnitude, and duration of mechanical stimulation.

PI3K/Akt Pathway in Mechanotransduction

Mechanism of Mechanical Activation

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway functions as a central hub in mechanotransduction, integrating signals from various mechanical stimuli including compressive forces, tensile stress, and fluid shear stress [19]. Mechanical activation of PI3K occurs through multiple mechanisms, including direct force transmission via integrin adhesions and cadherin-based cell-cell junctions, as well as through mechanosensitive ion channels such as Piezo1 [19] [20]. Once activated, PI3K phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which serves as a membrane docking site for pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-containing proteins including Akt and PDK1 [19]. Akt is subsequently phosphorylated at two key regulatory sites (Thr308 and Ser473), leading to its full activation and translocation to various subcellular compartments where it phosphorylates downstream targets [16].

Isoform-Specific Roles in Mechanical Signaling

Emerging evidence reveals isoform-specific functions for different class I PI3K catalytic subunits (p110α, p110β, p110δ, and p110γ) in mechanotransduction. PI3Kα has been linked to tensile and stretching adaptation through modulation of the actin cytoskeleton, while PI3Kβ responds to growth-induced compression and loss of organized cell-cell adhesion [19]. In breast and pancreatic cancer cells, compressive forces selectively induce overexpression of specific PI3K isoforms and enhance PI3K/Akt pathway activation, promoting cell survival under mechanical stress [20]. This isoform-specific regulation enables precise cellular responses to different types of mechanical stimuli and presents opportunities for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Downstream Effects and Functional Significance

The PI3K/Akt pathway regulates multiple cellular processes critical for mechanoadaptation. Activated Akt controls cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting pro-apoptotic proteins such as BAD and caspase-9, thereby protecting cells from mechanical stress-induced apoptosis [16]. The pathway also modulates oxidative stress responses through phosphorylation of Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors, leading to their nuclear exclusion and subsequent downregulation of antioxidant enzymes including glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) and Mn-superoxide dismutase [16]. Additionally, PI3K/Akt signaling influences cytoskeletal dynamics through regulation of small GTPases and their effectors, and serves as an upstream activator of the YAP/TAZ transcriptional pathway in response to mechanical cues [19]. In cancer contexts, PI3K activation under compression promotes migratory phenotypes and contributes to therapy resistance, highlighting its pathological significance [20].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models and Techniques

Research in mechanotransduction utilizes specialized methodologies to apply controlled mechanical stimuli and assess pathway activation:

- Four-Point Bending Devices: These systems apply precise mechanical tensile strain to cell cultures, typically at frequencies of 0.3 Hz and intensities of 5000-6000 µε, to investigate signaling responses to stretch [16].

- Compression Systems: Both 2D and 3D compression setups apply controlled compressive forces ranging from hundreds of Pascals to several kPa to model tumor microenvironment mechanics [20].

- Biaxial Loading Systems: Particularly valuable for studying anisotropic tissues like the diaphragm, these systems apply mechanical forces in both longitudinal and transverse directions to replicate in vivo loading conditions [21].

Assessment of Pathway Activity

- Western Blotting: Standard technique for quantifying phosphorylation levels of signaling components including Akt (Thr308, Ser473), FOXO1, and MAPK family members [16].

- Immunofluorescence Microscopy: Used to visualize cytoskeletal reorganization, focal adhesion formation, and subcellular localization of pathway components in response to mechanical stimuli.

- Transcriptional Reporters: Luciferase-based and GFP-reporters for YAP/TAZ activity and other mechanosensitive transcription factors to quantify pathway output [19].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanotransduction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/Akt Inhibitors | LY294002 | Pan-PI3K inhibitor | Blocks mechanical strain-induced apoptosis/senescence [16] |

| ROCK Inhibitors | Y27632, Y32885, HA1077 | ROCK kinase inhibition | Reduces actomyosin contractility, stress fiber formation [17] |

| PAK Inhibitors | PF-3758309, IPA-3 | PAK kinase inhibition | Blocks PAK1 autophosphorylation and activation [17] |

| Rho GTPase Inhibitors | MLS000532223 | Broad-spectrum Rho inhibitor | Inhibits GTP binding to Rho proteins [17] |

| GEF Inhibitors | ITX3 | Inhibits Trio GEF domain | Blocks Rac1 and RhoG activation [17] |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA/shRNA | Gene knockdown | Target-specific pathway components (e.g., PI3K isoforms, Rho GTPases) |

| Mechanical Strain | Four-point bending device | Application of tensile strain | Studies on hUSLF and other cell types [16] |

Integrated Pathway Crosstalk in Mechanotransduction

Network-Level Integration

The Rho GTPase, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt pathways do not function in isolation but rather form an integrated signaling network that processes mechanical information. Significant crosstalk exists between these pathways, enabling coordinated cellular responses to mechanical stimuli. PI3K signaling lies upstream of mechanically induced YAP/TAZ activation and also influences Rho GTPase activity through spatial regulation of PIP3 microdomains that recruit GEFs and GAPs [19]. Conversely, Rho GTPases can modulate PI3K/Akt signaling through cytoskeletal remodeling that alters membrane topography and receptor distribution. MAPK pathways integrate with both PI3K/Akt and Rho signaling through shared upstream regulators and convergent downstream targets, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that translates mechanical forces into precise biochemical responses [18] [19].

Pathophysiological Implications

Dysregulation of mechanotransduction pathways contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis. In cancer, compressive forces in solid tumors activate PI3K/Akt signaling to promote cell survival, migration, and therapy resistance [20]. In pelvic organ prolapse, mechanical strain on pelvic support fibroblasts activates PI3K/Akt-mediated oxidative stress, leading to apoptosis, senescence, and reduced collagen production that compromises tissue integrity [16]. Understanding the integrated function of these pathways in pathological contexts provides opportunities for novel therapeutic approaches targeting mechanotransduction, such as PI3K inhibitors in compressed tumors or ROCK inhibitors in fibrotic conditions [17] [20].

The Rho GTPase, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt pathways represent central signaling hubs in cellular mechanotransduction, each contributing distinct yet complementary functions in the conversion of mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals. The Rho GTPase family serves as a primary regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, the MAPK pathway provides quantitative sensing of mechanical tension, and the PI3K/Akt pathway functions as an integrative hub coordinating multiple mechanical responses. Together, these pathways form an interconnected network that enables cells to sense, interpret, and adapt to their mechanical environment through regulation of cytoskeletal organization, gene expression, metabolism, and cell survival decisions. Continued elucidation of the molecular mechanisms governing these pathways and their crosstalk will enhance our understanding of physiological processes and disease pathogenesis, potentially revealing novel therapeutic targets for conditions characterized by mechanotransduction dysregulation, including cancer, fibrosis, and musculoskeletal disorders. The development of isoform-specific inhibitors and mechanically-informed treatment strategies represents a promising frontier for future research and therapeutic innovation.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), collectively known as YAP/TAZ, have emerged as master regulators of cellular mechanotransduction, integrating diverse mechanical and biochemical signals to control cell proliferation, differentiation, and fate. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms through which YAP/TAZ translates extracellular mechanical cues into transcriptional programs, with particular focus on their role as nuclear effectors of cytoskeleton-mediated signaling pathways. We synthesize current understanding of the integrated mechanochemical signaling network regulating YAP/TAZ activity, detail experimental methodologies for probing its function, and discuss implications for therapeutic targeting in disease contexts characterized by mechanotransduction dysregulation.

YAP/TAZ serves as a critical signaling nexus that integrates diverse mechanical and biochemical signals from the cellular microenvironment, including extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness, adhesion ligand density, cell-cell contacts, and fluid shear stress [22] [8]. Originally discovered as effectors of the Hippo pathway regulating organ size, YAP/TAZ is now recognized as a fundamental readout of cellular mechanotransduction with roles in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease pathologies such as cancer and fibrosis [23]. These transcriptional coactivators lack DNA-binding domains but partner with transcription factors (primarily TEADs) to regulate genes controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [22]. The mechanical regulation of YAP/TAZ occurs through both Hippo-dependent and Hippo-independent pathways, with particular dependence on RhoA-regulated stress fibers and actomyosin contractility [22] [23]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms of YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness within the broader context of cytoskeleton-mediated mechanotransduction pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms of YAP/TAZ Mechanical Regulation

Integrated Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathway

The mechanoregulation of YAP/TAZ involves a sophisticated signaling network that converts extracellular mechanical properties into biochemical signals that ultimately control YAP/TAZ nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and transcriptional activity. The integrated pathway encompasses mechanical sensing at adhesion complexes, intracellular signal transmission through Rho GTPases, cytoskeleton dynamics, and regulation of YAP/TAZ activity through both mechanical and biochemical effectors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Integrated YAP/TAZ Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the molecular network through which mechanical cues regulate YAP/TAZ activity. The pathway begins with mechanical sensing at the cell membrane, progresses through intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal reorganization, and culminates in regulation of YAP/TAZ nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and transcriptional activity.

Key Mechanical Inputs Regulating YAP/TAZ

Cells encounter multiple mechanical cues in their microenvironment that influence YAP/TAZ activity through the integrated pathway described above. These mechanical inputs are transduced into biochemical signals through specific mechanosensors and signaling cascades.

Table 1: Mechanical Cues Regulating YAP/TAZ Activity

| Mechanical Cue | Typical Physiological Range | Primary Sensors | YAP/TAZ Response | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM Stiffness | 0.1-100 kPa [24] | Integrins, Focal Adhesions [22] | Nuclear localization increases with stiffness [22] [23] | Stem cell differentiation, Tumor progression |

| Fluid Shear Stress | 1-50 dyn/cm² [8] | Piezo1, Primary Cilia [8] | Context-dependent activation [8] | Vascular remodeling, Bone homeostasis |

| Tensile Force/Stretch | Variable by tissue | Integrins, Cadherins [8] | Nuclear localization [8] | Lung ventilation, Muscle contraction |

| Extracellular Fluid Viscosity | 1-10 cP [8] | Unknown | Enhanced nuclear localization [8] | Tumor microenvironment, Mucociliary clearance |

| Cell Confinement/Shape | N/A | Cytoskeleton, Nucleoskeleton [23] | Reduced nuclear localization with confinement [23] | 3D culture, Tissue morphogenesis |

Computational Modeling Insights

Computational approaches have been instrumental in deciphering the complex regulation of YAP/TAZ. Mathematical models have revealed how different signaling molecules affect YAP/TAZ stiffness response functions and have helped resolve seemingly contradictory experimental findings.

Table 2: Key Insights from Computational Models of YAP/TAZ Signaling

| Modeling Approach | Key Predictions | Experimental Validation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODE-based Well-Mixed Model | FAK overexpression rescues YAP/TAZ activity on soft substrates; mDia upregulation increases YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation | Mimicked molecular interventions (inhibition/overexpression of myosin, ROCK, RhoA, F-actin, mDia) | [22] [23] |

| Spatial Reaction-Diffusion Models | Cell shape and culture dimensionality significantly impact YAP/TAZ response to stiffness; nuclear flattening regulates YAP/TAZ | Comparison of 2D vs. 3D culture systems; cell shape manipulation experiments | [23] |

| Integrated Adhesion-Cytoskeleton Models | YAP/TAZ more sensitive to ECM changes than SRF/MAL; LATS-LIMK interaction explains Hippo-mechanosensing synergy | Stiffness response curves in multiple cell types; LIMK perturbation experiments | [22] [23] |

Experimental Methodologies for YAP/TAZ Mechanotransduction Research

Core Workflow for Mechanotransduction Studies

Investigating YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness requires specialized methodologies that enable controlled application of mechanical stimuli and accurate measurement of downstream responses. The following workflow outlines key experimental approaches for dissecting YAP/TAZ mechanotransduction (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Experimental Workflow for YAP/TAZ Mechanotransduction Studies. This diagram outlines the key methodological approaches for investigating YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness, from experimental design and mechanical stimulation to molecular perturbation and downstream readouts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for YAP/TAZ Mechanotransduction Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Substrates | Polyacrylamide gels, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Control substrate stiffness from 0.1-100 kPa | ECM stiffness sensing; Tensional homeostasis [24] [8] |

| Mechanosensor Modulators | Yoda1 (Piezo1 agonist), GsMTx4 (mechanosensitive channel blocker) | Activate or inhibit specific mechanosensors | Distinguish specific mechanosensory pathways [8] |

| Cytoskeleton Targeting Agents | Latrunculin A (F-actin disruptor), Cytochalasin D (actin polymerization inhibitor), Blebbistatin (myosin II inhibitor) | Perturb cytoskeletal organization and contractility | Role of stress fibers and actomyosin contractility [24] [22] |

| Rho GTPase Modulators | CN03 (RhoA activator), C3 transferase (RhoA inhibitor), Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Manipulate RhoA-ROCK signaling axis | RhoA-mediated regulation of YAP/TAZ [22] [23] |

| Hippo Pathway Modulators | XMU-MP-1 (MST1/2 inhibitor), Verteporfin (YAP-TEAD interaction inhibitor) | Target Hippo kinase cascade and YAP transcriptional activity | Distinguish Hippo-dependent vs independent regulation [23] |

| YAP/TAZ Localization Reporters | YAP/TAZ-GFP fusion constructs, Immunofluorescence antibodies (anti-YAP/TAZ) | Visualize and quantify nucleocytoplasmic shuttling | Direct readout of YAP/TAZ mechanical activation [22] [23] |

Quantitative Assessment of YAP/TAZ Activation

Accurate quantification of YAP/TAZ activity is essential for mechanistic studies. Multiple complementary approaches provide quantitative readouts of YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness.

Table 4: Quantitative Methods for Assessing YAP/TAZ Activity

| Method | Measured Parameters | Technical Considerations | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunofluorescence & Image Analysis | Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio; Absolute nuclear intensity | Requires careful segmentation and normalization; sensitive to fixation artifacts | Subcellular localization; single-cell heterogeneity |

| Gene Expression Analysis | YAP/TAZ target genes (CTGF, CYR61, ANKRD1) | Direct measure of transcriptional activity; may reflect integrated signaling over time | Functional transcriptional output |

| Biochemical Fractionation & Western Blot | Absolute YAP/TAZ protein levels in nuclear vs. cytoplasmic fractions | Population average; potential cross-contamination during fractionation | Molecular quantification; post-translational modifications |

| FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) | Nuclear import/export kinetics | Requires YAP/TAZ fluorescent protein fusions; phototoxicity concerns | Dynamic nucleocytoplasmic shuttling rates |

| TEAD Luciferase Reporter Assays | YAP/TAZ-TEAD transcriptional activity | Population average; sensitive to transfection efficiency | Specific YAP/TAZ-TEAD functional interaction |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

The mechanical regulation of YAP/TAZ has profound implications for human health and disease. In normal physiology, YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness contributes to tissue development, homeostasis, and regeneration. However, dysregulation of mechanical signaling can drive disease progression through aberrant YAP/TAZ activation.

In cancer progression, increased ECM stiffness associated with tumor desmoplasia promotes YAP/TAZ nuclear localization, driving proliferation and invasion [24] [8]. Stiff mechanical environments hyperactivate a mechanically regulated signaling loop that increases expression of carcinoma-associated proliferation genes [24]. Similarly, in fibrotic diseases, persistent mechanical stress sustains YAP/TAZ activation, promoting excessive ECM deposition by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts [8].

Therapeutic strategies targeting YAP/TAZ mechanical activation are emerging, including direct YAP/TAZ-TEAD interaction inhibitors, Rho-ROCK pathway inhibitors, and mechanosensitive ion channel modulators [8] [23]. Additionally, approaches that normalize the mechanical tumor microenvironment (e.g., LOXL2 inhibitors to reduce ECM crosslinking) show promise for indirectly modulating YAP/TAZ activity. The development of context-specific therapeutic interventions requires careful consideration of the dual roles of YAP/TAZ in tissue homeostasis and disease, necessitating sophisticated spatiotemporal control of targeting strategies.

YAP/TAZ represents a fundamental nuclear connection in cellular mechanotransduction, integrating diverse mechanical cues into coherent transcriptional programs that dictate cell fate and behavior. The mechanistic understanding of YAP/TAZ mechanoresponsiveness has advanced significantly through combined experimental and computational approaches, revealing a complex signaling network centered on cytoskeletal regulation.

Future research directions include elucidating the spatiotemporal dynamics of YAP/TAZ mechanical activation in living cells and tissues, deciphering the role of nuclear mechanics in YAP/TAZ regulation, and developing more sophisticated computational models that incorporate multi-scale mechanical signaling. Additionally, translating mechanistic insights into therapeutic applications requires better understanding of YAP/TAZ regulation in human pathophysiology and development of targeted interventions that specifically disrupt pathological mechanical signaling while preserving physiological YAP/TAZ functions. The continued integration of mechanical and molecular perspectives will be essential for fully understanding the nuclear connection of YAP/TAZ in health and disease.

Physiological Roles in Embryonic Development, Tissue Repair, and Homeostasis

Mechanotransduction, the process by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals, is a fundamental biological mechanism governing cellular behavior in health and disease. This process is orchestrated by a complex network of cytoskeletal elements, signaling pathways, and nuclear effectors that enable cells to sense and respond to their physical microenvironment. Within physiological contexts, mechanotransduction plays critical roles in guiding embryonic development, facilitating tissue repair, and maintaining cellular homeostasis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the mechanisms underlying these processes, with particular emphasis on cytoskeletal signaling pathways and their implications for therapeutic development. Through integration of current research findings and experimental methodologies, this review aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of how mechanical forces shape biological outcomes across diverse physiological systems.

Core Mechanisms of Mechanotransduction

Key Cellular Components and Signaling Pathways

The cellular mechanotransduction apparatus comprises several interconnected systems that work in concert to detect, transmit, and respond to mechanical cues. Central to this process are integrins, which serve as primary sensors of extracellular mechanical cues by binding to extracellular matrix (ECM) components. This binding induces integrin clustering and activation, leading to the recruitment of focal adhesion complexes that physically link the ECM to the intracellular actin cytoskeleton [25] [3]. The force-dependent unfolding of focal adhesion proteins such as talin reveals cryptic binding sites for vinculin, thereby reinforcing the adhesion complex and promoting downstream signaling through activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases [3].

The cytoskeleton serves as both a structural framework and signaling intermediary in mechanotransduction. Composed of actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, this dynamic network transmits forces from adhesion sites to intracellular compartments, including the nucleus [9] [21]. Force-induced cytoskeletal rearrangements activate key signaling pathways, including RhoA/ROCK, which regulates actomyosin contractility, and the Hippo pathway effectors YAP/TAZ, which translocate to the nucleus to modulate gene expression programs in response to mechanical cues [26] [9]. These pathways collectively enable cells to adapt their behavior based on physical properties of their environment, including substrate stiffness, fluid shear stress, and tensile forces.

Table 1: Core Components of the Mechanotransduction Machinery

| Component Category | Key Elements | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanosensors | Integrins, Piezo channels, Cadherins | Detect extracellular mechanical forces and matrix properties |

| Cytoskeletal Elements | F-actin, Microtubules, Intermediate filaments (e.g., Desmin) | Transduce forces intracellularly, provide structural support |

| Signaling Hubs | Focal adhesions, Adherens junctions, Perinuclear actin cap | Integrate mechanical and biochemical signals |

| Nuclear Effectors | YAP/TAZ, MRTF, LINC complex | Transmit signals to the nucleus, regulate gene expression |

From Force to Biochemical Signal: Molecular Transduction

The conversion of physical forces into biochemical information occurs through several molecular mechanisms. At focal adhesions, mechanical tension induces conformational changes in proteins such as talin and p130Cas, exposing phosphorylation sites and binding domains that initiate signaling cascades [3]. This leads to the activation of downstream pathways including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and Rho GTPase signaling, which coordinate cellular responses such as proliferation, survival, and migration [25] [3]. The mechanosensitive transcription factors YAP and TAZ are particularly important integrators of mechanical signals, shuttling to the nucleus when mechanical tension is high to promote expression of genes supporting cell growth and differentiation [26] [9].

Recent research has elucidated the role of nuclear mechanics in mechanotransduction. External forces transmitted via the cytoskeleton can directly deform the nucleus, influencing chromatin organization and gene expression [27] [28]. Studies in pluripotent stem cells have demonstrated that compression-induced nuclear deformation triggers osmotic stress responses, chromatin remodeling, and altered transcriptional activity, effectively priming cells for fate transitions [27]. This mechano-osmotic regulation provides a direct link between physical forces and epigenetic regulation, expanding our understanding of how mechanical cues influence cell identity and function.

Physiological Role in Embryonic Development

Mechanical Regulation of Cell Fate Transitions

Embryonic development is characterized by precisely coordinated morphological transformations guided by both biochemical and mechanical cues. Recent studies investigating pluripotent stem cells and early mammalian embryos have revealed that cell fate transitions are associated with rapid changes in nuclear morphology and volume, suggesting a role for mechano-osmotic signals in developmental patterning [27] [28]. In human pluripotent stem cells exiting the primed pluripotent state, removal of growth factors FGF2 and TGF-β triggers rapid nuclear volume reduction and increased nuclear envelope fluctuations within minutes, preceding transcriptional changes associated with differentiation [27]. This nuclear remodeling is mediated by cytoskeletal confinement and changes in chromatin mechanics, ultimately leading to global transcriptional repression and a condensation-prone nuclear environment that primes cells for fate transitions.

The mechanical microenvironment plays a crucial role in embryonic pattern formation. Research utilizing a computational framework for spatial mechano-transcriptomics has demonstrated that boundaries between tissue compartments in the developing mouse embryo are characterized by distinct mechanical signatures, including elevated interfacial tension at heterotypic cell junctions [29]. This mechanical compartmentalization works in concert with biochemical signaling to establish precise tissue boundaries during gastrulation. The interplay between mechanical forces and gene expression patterns enables the emergence of complex morphological structures from initially homogeneous cell populations, highlighting the integral role of mechanotransduction in developmental processes.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Mechanical Regulation of Embryonic Development

| Experimental System | Key Mechanical Manipulation | Quantitative Findings | Developmental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| hiPSC differentiation | Removal of FGF2/TGF-β factors | 15 min: 15-20% ↓ nuclear volume5 min: ↑ nuclear envelope fluctuations5 min: ↑ nuclear stiffness via AFM | Priming for differentiation via chromatin reorganization |

| Mouse embryo (E8.5) | Spatial force inference mapping | TAB > max(TAA, TBB) at boundaries2-3x ↑ interfacial tension at heterotypic contacts | Boundary formation between tissue compartments |

| Human blastoid models | Osmotic stress induction | 30-40% ↓ nuclear volume in GATA6+ cellsActivation of p38 MAPK osmosensitive pathway | Hypoblast lineage specification |

Methodologies for Studying Developmental Mechanobiology

Investigating mechanical influences on embryonic development requires specialized methodologies capable of quantifying forces and cellular responses in developing systems. Force inference approaches based on cell morphology measurements enable researchers to calculate interfacial tensions and intracellular pressures from static images of embryonic tissues [29]. This method involves segmentation of cell boundaries from fluorescent membrane markers, resolution of multicellular junctions, and application of mechanical equilibrium principles to infer tension values. The variational method of stress inference (VMSI) has demonstrated particular utility in developmental contexts, offering robustness against measurement noise and capacity to resolve pressure differentials between adjacent cells [29].

Live imaging approaches provide complementary dynamic information about mechanical processes during development. For studying nuclear mechanotransduction, endogenously tagged fluorescent markers (e.g., LaminB-RFP) enable quantification of nuclear envelope fluctuations using fast confocal microscopy [27] [28]. These fluctuations serve as indicators of actomyosin-dependent forces acting on the nucleus and can be quantified through analysis of envelope displacement over time. Combined with pharmacological inhibition of cytoskeletal dynamics (e.g., using Cytochalasin D for actin, Nocodazole for microtubules) and ATP depletion approaches, this methodology enables researchers to dissect the relative contributions of different force-generating systems to nuclear mechanical regulation [27].

Physiological Role in Tissue Repair

Mechanoperception in Repair and Regeneration

Tissue repair processes rely on precise mechanoperception to coordinate cellular responses appropriate to the injury environment. Fibroblasts, key effector cells in wound healing, exhibit stiffness-dependent activation states that normally promote repair in mechanically compliant environments while inhibiting excessive activation on stiff substrates [30]. This mechanosensitive behavior is mediated by Thy-1 (CD90), a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein that regulates integrin αv activation in a stiffness-dependent manner. In soft tissue environments, Thy-1 maintains integrin αv in an inactive conformation, preventing aberrant fibroblast activation; however, on stiff substrates, inside-out activation signals overcome Thy-1 inhibition, permitting normal mechanotransduction [30].

Dysregulation of mechanosensing pathways underlies pathological repair processes such as fibrosis. Thy-1 loss results in misinterpretation of mechanical cues, leading to fibroblast activation and differentiation into myofibroblasts even in soft environments that normally inhibit this transition [30]. Multi-omics analyses of Thy-1 knockout fibroblasts have revealed substantial reprogramming of transcriptional and epigenetic states, including near-complete silencing of HOXA5, a transcription factor critical for pulmonary development and patterning [30]. This aberrant mechanoperception disrupts normal tissue repair programs and promotes pro-fibrotic phenotypes, highlighting the importance of precise mechanical signaling for regenerative outcomes.

Experimental Models for Tissue Repair Mechanobiology

In vitro models of tissue repair enable systematic investigation of mechanical factors in controlled environments. 2D micropatterning approaches, sometimes termed "2D gastruloids," allow precise control of cell shape and mechanical context while monitoring differentiation outcomes [27]. These systems typically involve plating cells on defined adhesive patterns of varying geometry and size, often combined with controlled substrate stiffness through use of polyacrylamide or polydimethylsiloxane (PDX) hydrogels with tunable elastic moduli. Such platforms have revealed that colony compaction precedes lineage specification during differentiation, with associated nuclear deformation and activation of mechanosensitive pathways including YAP and p38 MAPK [27].

For investigating fibrosis mechanisms, combinatorial screening approaches incorporating multiple mechanical and biochemical variables provide comprehensive insights into disease pathogenesis. In studies of pulmonary fibrosis, researchers have employed ATAC- and RNA-sequencing in parallel to characterize epigenetic and transcriptional changes in lung fibroblasts across gradients of substrate stiffness and culture time [30]. This multi-omics approach has identified key regulatory networks linking mechanical sensing to developmental pathways, particularly highlighting the role of αv integrin signaling and SRC kinase activity in silencing HOXA5 expression under pro-fibrotic conditions.

Physiological Role in Homeostasis

Maintenance of Tissue Integrity and Function

In mature tissues, mechanotransduction pathways maintain homeostasis by enabling cells to continuously adapt to changing mechanical demands. The diaphragm muscle provides a compelling example of specialized mechanosensing in a mechanically active tissue. Unlike most skeletal muscles that experience primarily unidirectional loads, the diaphragm undergoes biaxial loading during respiration, with forces applied both parallel and perpendicular to muscle fibers [14] [21]. This unique mechanical environment has driven the evolution of specialized mechanotransduction pathways that respond anisotropically to direction-specific stresses. Research has demonstrated that stretching the diaphragm in longitudinal versus transverse directions activates distinct signaling pathways, with cytoskeletal proteins such as desmin playing critical roles in integrating these directional mechanical cues [21].

The cytoskeleton serves as a key mediator of mechanical homeostasis across diverse tissues. Intermediate filaments like desmin form networks that connect adjacent Z-disks in muscle fibers, providing structural integrity while facilitating mechanical signal transmission [21]. Studies in desmin-null mice have revealed significant reductions in coupling between longitudinal and transverse mechanical properties in diaphragm muscle, demonstrating the importance of this cytoskeletal component in maintaining three-dimensional tissue organization [21]. Similarly, in intervertebral discs, chondrocytes respond to complex mechanical stimuli including compression, tension, and osmotic pressure to maintain tissue homeostasis, with aberrant mechanical loading leading to degenerative changes [26].

Methodologies for Studying Tissue Homeostasis

Ex vivo tissue stretching systems enable investigation of mechanotransduction in physiologically relevant contexts. Biaxial loading systems for diaphragm muscle studies allow independent control of longitudinal and transverse stresses, mimicking the in vivo mechanical environment [21]. These systems typically involve mounting tissue samples between computer-controlled actuators and force transducers, enabling precise application of multidirectional strains while monitoring tissue responses. Using this approach, researchers have demonstrated that transverse stretching modulates both passive and active mechanical properties of diaphragm muscle, an effect that is abolished in desmin-deficient tissue [21].

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) provides nanoscale resolution of mechanical properties in living cells and tissues. In studies of nuclear mechanics, AFM force indentation spectroscopy has revealed that removal of pluripotency-maintaining growth factors triggers rapid nuclear stiffening within 5 minutes, with FGF2 signaling playing a predominant role in maintaining the compliant nuclear state characteristic of pluripotent cells [28]. This methodology involves bringing a precisely calibrated tip into contact with the cell surface while monitoring deflection, enabling calculation of local stiffness based on force-displacement relationships. Combined with genetic encoders of mechanical properties such as nucGEMs (nuclear Genetically Encoded Multimeric nanoparticles), AFM enables correlation of structural mechanics with molecular composition [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mechanotransduction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Modulators | Cytochalasin D, Nocodazole, Latrunculin B, Jasplakinolide | Disruption of cytoskeletal dynamics | Depolymerize (or stabilize) actin filaments and microtubules to test force transmission mechanisms |

| Mechanosensing Inhibitors | Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor), Verteporfin (YAP inhibitor), PF573228 (FAK inhibitor) | Pathway-specific inhibition | Block specific mechanotransduction signaling nodes to establish necessity |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | LaminB-RFP, nucGEMs, YAP/TAZ localization reporters, FRET tension sensors | Live imaging of mechanical responses | Visualize subcellular reorganization, molecular trafficking, and force-dependent conformational changes |

| Engineered Substrates | Polyacrylamide hydrogels, PDMS micropatterns, stiffness-tunable matrices | Control of mechanical microenvironment | Present defined mechanical cues (stiffness, topography) to cells in culture |

| Integrin Function Modulators | RGD peptides, integrin-activating/blocking antibodies, Thy-1 inhibitors | Manipulation of adhesion signaling | Perturb specific integrin-mediated mechanosensing pathways |

| Osmotic Stress Inducers | Sorbitol, NaCl hypertonic media, Calyculin A | Control of cell volume and nuclear state | Induce osmotically-driven mechanical changes independent of substrate mechanics |

Mechanotransduction represents a fundamental biological process through which cells perceive and respond to physical cues in their environment, playing critical roles in embryonic development, tissue repair, and homeostatic maintenance. The cytoskeleton serves as both structural scaffold and signaling intermediary in these processes, integrating mechanical information from the extracellular environment and transducing it into biochemical signals that direct cellular behavior. Current research has illuminated the complex molecular networks underlying mechanotransduction, revealing sophisticated mechanisms for force detection, transmission, and response at cellular and tissue levels. Understanding these processes provides critical insights for therapeutic development, particularly for conditions characterized by mechanical dysregulation such as fibrosis, degenerative disorders, and developmental abnormalities. As methodologies for studying cellular mechanics continue to advance, including sophisticated force measurement techniques and multi-omics approaches, our capacity to intervene therapeutically in mechanotransduction pathways will expand, offering new opportunities for targeting these fundamental processes in human health and disease.

Advanced Techniques and Therapeutic Targeting in Mechanotransduction Research

Cell culture has become an indispensable tool for uncovering fundamental biophysical and biomolecular mechanisms by which cells assemble into tissues and organs, how these tissues function, and how that function becomes disrupted in disease [31]. For over a century, two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures have served as primary in vitro models to study cellular responses to biophysical and biochemical cues. However, growing evidence demonstrates that 2D systems can result in cell bioactivities that deviate appreciably from in vivo responses, particularly for certain cell types like cancer cells [31]. This recognition has spurred substantial efforts toward developing three-dimensional (3D) biomimetic environments that better recapitulate the topographically complex, information-rich extracellular environments in which cells routinely operate in vivo [32].

The transition from 2D to 3D culture systems represents more than just a technical advancement—it fundamentally changes how cells perceive and respond to their mechanical environment. Mechanical properties of extracellular matrices (ECMs) regulate essential cell behaviors, including differentiation, migration, and proliferation through mechanotransduction—the process by which cells sense and convert mechanical signals into biochemical responses [33]. While studies of cell-ECM mechanotransduction have largely focused on cells cultured in 2D, emerging research reveals that mechanisms of mechanotransduction can differ significantly in 3D contexts native to most cells in vivo [33]. This technical guide examines the fundamental differences between 2D and 3D experimental model systems for studying cellular mechanics, with particular emphasis on their implications for understanding mechanotransduction and cytoskeleton signaling pathways.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Culture Systems

Core Characteristics of 2D and 3D Microenvironments

The microenvironment in which cells are cultured profoundly influences their behavior, signaling, and mechanical responses. The table below summarizes the key differences between traditional 2D and more physiologically relevant 3D culture systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture Systems

| Feature | 2D Culture Systems | 3D Culture Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Organization | Flat, monolayer growth with unnatural apical-basal polarity [31] | Volumetric growth with natural cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions [32] |

| Mechanical Forces | Forces applied primarily in one plane; uniform mechanical stress distribution [32] | Complex, multi-axial force application; heterogeneous mechanical stress distribution [33] |